|

October 1960 Electronics World

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Most of us, long before being

introduced to the concept of power in electrical circuits, learn about it in terms

of mechanical power and/or sound power. It takes some doing to abandon the esoteric

nature of power and be trained to grasp the scientific and mathematical aspects

of power in all its forms. When the driving source is steady state or a pure sinewave,

life is relatively simple, but such is more often than not an exception to the system

being studied. Here is a nice, short treatise in a 1960 issue of Electronics

World magazine on the concept of sound power that will augment your earlier-learned

knowledge of music power rating.

Music Power Rating - Help or Hindrance?

By Norman H. Crowhurst By Norman H. Crowhurst

This author's provocative view is that this amplifier rating is a step in the

right direction, however it may not tell the whole story about hi-fi performance.

The question that triggered this article is, "Does the new Music Power Rating

help tell the quality of amplifier ? If so, how?" The answer to this question will

be covered later, but mainly some concepts, notions, and viewpoints need clarifying

first. There will be some explaining to do - why the particular Music Power Output

definition, as used by the IHFM (Institute of Hi Fidelity Manufacturers) standard

for rating amplifiers, was chosen, as well as what it can tell us.

For a long while, the accepted methods of rating or specifying amplifier performance

have been recognized as inadequate for assessing the relative merit of different

products. This has been correctly related to the fact that music, or other program

material, is different in many respects from the pure-tone sine waves used for testing

amplifiers.

These two standards differ in two respects: all test tones, whether one or two

sine waves, or a square wave, are applied steadily, while the tones in music are

constantly changing, often rapidly. Apart from their transient nature, musical waveforms

are much more complicated than anything used for testing, even when the tones are

steady.

Some Viewpoints

Engineers in the high-fidelity industry have, for some time, been concerned by

this discrepancy. Some have tried to do something about it and some have even dared

to try and make an amplifier whose first job was to sound good, even if its specifications

didn't read quite as impressively! But these engineers soon ran into opposition.

Some people either are not able to listen critically or else don't believe their

ears. They want something in print that they can show around, proving that the product

they have is better. We have no argument with this attitude. The difficulty is,

what figures can we provide that really prove something? The notion of music power

output originated with engineers: it should be a way of rating amplifiers which

will more nearly evaluate how "loud" they will sound, than does the conventional

power output rating.

One problem is that steady power tests force the amplifier to deliver its maximum

power continuously. Musical program material calls for maximum power for only short

periods of time. Why not see what an amplifier will produce when the demand is not

continuous?

If you put just one or two cycles of a frequency through an amplifier you can

see its performance during such a short burst but you cannot measure it because

the meters won't have time to "get up to" whatever the reading is. To overcome this,

the method specified by the IHFM involves the maintenance (artificially), from an

external source, of the voltages that sag under continuous power for long enough

to get the reading.

This sounds good, when it is explained to you, otherwise it might appear to be

"cheating a bit." Next, you want to know what the "answers" mean. And that is a

good question. Until most audiophiles and hi-fi equipment makers use the music power

rating, the more familiar continuous output power will also be given. So your question

is: which is better, an amplifier that has both ratings the same, or nearly the

same, or one for which the music power is appreciably higher than the continuous

power?

Pursuing this question reveals the fact that an amplifier with good power-supply

regulation will have ratings which are closer together while one whose power supply

provides poorer regulation will show a greater difference between continuous and

music power ratings. Surely the amplifier with the better regulated power supply

is the better amplifier? Put it this way: do you want quality watts per dollar or

are you looking for the highest power irrespective of cost?

One amplifier may have both ratings at 25 watts. Another unit, by spending part

of what the first spent on the power supply on other features, may give 25 watts

continuous but also manages 35 watts music power as well. The second amplifier will

undoubtedly provide greater clean music volume - other things being equal - than

the first unit.

But we have no objection to a third amplifier that gives 35 watts measured both

ways, if the manufacturer can make it competitively. It is an even better amplifier

than the second one, but whether it is worth paying the 30% to 40% higher price

is up to the buyer to decide.

This is, roughly, the way the new music power rating works out. It is a step

forward. but some engineers are still no satisfied. While it does come nearer to

some aspects of how an amplifier performs on music, it still misses some points.

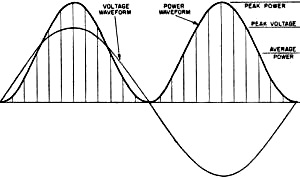

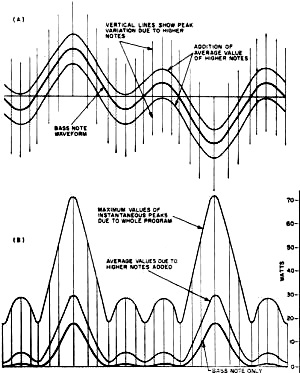

Fig. 1 - Comparison of voltage and power waveforms for (A,

above) simple sine wave and (B, below) musical tone consisting of a fundamental

with considerable third harmonic.

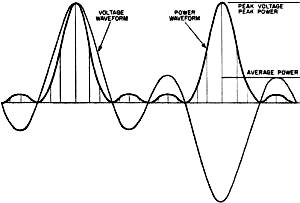

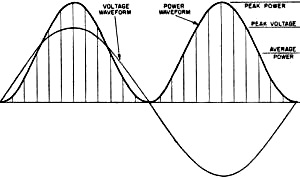

Fig. 2 - The effect of combining two tones of different

frequency on the relationship between the peak and average power.

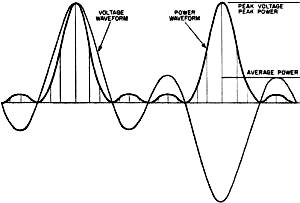

Fig. 3 - Voltage and power relations that exist in an audio

amplifier when three different tones are combined.

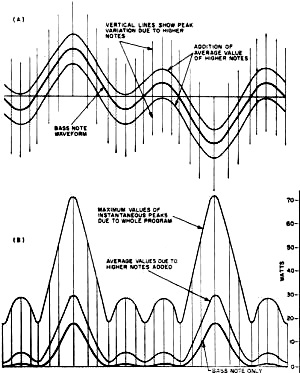

Fig. 4 - Voltage and power levels that exist in musical

phrase in which there are 1 bass and 3 mid-range notes.

Another Look at Waveforms

What is the true relationship between the power in a musical program and the

maximum power as measured by a single tone? This is the question the new music power

rating does not really touch because both ratings, by definition, measure average

power. Average music power can have a number of different connotations, while the

average power of a sine-wave output is unambiguous.

It was the transient nature of music power that dictated the new rating. But

even a steady tone, such as that played by a single instrument, can have quite a

different average power from that of a sine wave, in terms of what an amplifier

can handle. See Fig. 1.

The limitation to the handling capacity of an amplifier is the instantaneous

peak power it can deliver. The peak power of a 10-watt sine wave is 20 watts. But

a musical tone with 20 watts peak may very well have an average power of less than

5 watts - even as a single continuous tone. That is really the first basis for differences.

It affects the rating question in two ways. First, the lower "waveform factor"

means the regulation will not hurt even a sustained tone's power as much as with

the test sine waves (unless the sustained tone is sinusoidal, approaches a square

shape, or has a "waveform factor" such that its average value is higher than a sine

wave - Editor.) Second, it alters the picture as to what "average power" itself

really means.

Next point: music consists of many tones played at any single instant - most

of the time. Each tone has a different frequency. At a frequency corresponding to

this difference, the peaks of two tones will coincide. At each such coincidence,

it is the voltage, not the power, that adds to determine the total peak. If peak

voltage doubles, peak power is quadrupled, as shown in Fig. 2.

Suppose each of three tones has an average power of .5 watt and a peak power

of 2 watts. If the impedance is 8 ohms, each peak will be 4 volts. Three of them

will reach occasional "spikes" of 12 volts (Fig. 3). This is a power of 18

watts, although the average is only 1.5 watts. If a pedal tone is also present,

it may need a further 5-watts average with perhaps IS-watts peak, also 12 volts.

Now we need 24 volts, which is 72-watts peak, for just a pedal tone and trichord,

totaling an average power of 6.5 watts. See Fig. 4.

The more complex the music, the greater the basic factor between average and

peak power. You may have noticed that orchestral music at a certain nominal output

power does not seem as loud as, say, a jazz combo.

This because the ear recognizes the sum of all the average powers. To make the

reckoning easy, let's assume each instrument contributes 0.5 watt average

power and needs 2 watts or 4 volts peak.

A four-piece combo will give 2 watts average, but needs 16 volts or 32 watts

peak power. A 40-piece orchestra will give 20 watts average, but needs 160 volts

or 3200 watts peak power! Nobody has that kind of power, so assume we play with

the same margin of safety against possible distortion: the four-piece combo can

be played at a realistic level of 2 watts average from a 16-watt amplifier (32 watts

peak) ; but the orchestra will have to be turned down to only one-fifth of a watt

total average, to stay within 32 watts peak.

This explains why a much bigger amplifier is needed to handle good orchestra

music, even though the sound doesn't seem any louder - if as loud. It also explains

why no single music power rating, based on an average, can ever be completely practical.

With so many variables, the only point of common reference between amplifiers

and the music they handle is peak power. This is what determines when the amplifier

starts to distort the music. The average power that corresponds to this peak power

depends entirely on the music, not the amplifier. The "waveform factor" may react

on the power-supply regulation to modify the peak capability according to what the

average power is. But even the worst power-supply regulation usually makes little

difference on this, with most kinds of music.

There was a move, some years ago, to rate amplifiers by peak power. Proposed

with honest intentions, it was based on similar reasoning but the simple two-to-one

relationship for test sine waves led to its serious misuse.

Give a Dog a Bad Name!

The intention was not to just double the number already on the amplifier nameplate,

but this is what many companies did. The peak power intended was what the amplifier

could handle on peaks, representative of the relative duration encountered in music.

But insufficient explanation, plus the urge by some just to use bigger numbers,

led to confusion .

Some firms measured peak power the way the IHFM now defines music power. It was

really a short-term average power. Others double the number they already had, based

on the mathematical sine-wave relationship. Yet others doubled the short-term average

power, giving the instantaneous peak value of such a wave - and the highest number

of all.

This last figure was really the most logical and, if everyone used it, would

be the most informative regarding amplifier performance because it does relate directly

to the musical program the amplifier can handle.

But the fact that so many methods of rating were used, led many to believe that

the "good old standard" watts were "honest watts", with the obvious implication

that the others were cheating - "just doubling the numbers to make the amplifier

look bigger!"

This was understandable. If the new number really told something extra about

the amplifier's performance, it was useful. But most often it was obtained by the

arithmetical operation of multiplying by two. This had no value, except to further

confuse the already confused consumer.

Experiences like this are difficult to live down. On the committee that discussed

the new IHFM music power rating, several engineers favored the use of a peak music

power rating. This would double the figure as presently defined. But they remembered

the hangover of adverse criticism from the last attempt and compromised by using

the present definition.

Pots and Kettles

This compromise is not unreasonable when you consider some other factors. Most

important among these: what does the power rating of a loudspeaker mean? It is intended

to be the electrical input power the speaker can handle, as delivered by the amplifier.

A 10-watt speaker with 10% efficiency (and that's high) should be able to take in

10 electrical watts and deliver 1 acoustic watt - maximum. But it is called a 10-watt

speaker.

That's not all. Few loudspeakers, rated at 10 watts, will handle this much input

power at a single sinusoidal frequency, through the range for which they are designed

- which most good amplifiers do with ease. But the same loudspeakers are quite happy

handling the maximum musical power a 10-watt amplifier can deliver, which is a mixture

of many frequencies, with a low waveform factor.

Taken in conjunction with this fact, and other inconsistencies we haven't space

to explain here, it is not so illogical to rate amplifiers according to the new

IHFM music power definition. So let's take another look at that question, "Does

the new Music Power Rating help tell the quality of an amplifier?"

What Good is MPR?

If you want to use all the figures you can get hold of about every available

amplifier, you will probably try to make some deductions for which the published

information was never intended. In introducing music power rating, the intention

is to bring into use a figure for comparison that is more realistic than the one

now used.

During a transitional period, progressive manufacturers will have to use both

ratings, not to provide more information about their own product, but so that comparison

can still be made with other products that do not yet use the new rating. It is

hoped that all firms will ultimately use music power rating - at least as the main

figure.

For simplicity, most people do not want to digest a whole catalogue of specifications

about each product. From this standpoint, music power rating is a more informative

single figure than continuous power rating. If you are sufficiently interested,

continuous power rating, as a second figure, will convey an additional measure of

merit.

We should not compare amplifiers with the same continuous power ratings and different

music power ratings. When both figures are given, we would compare amplifiers first

by music power rating; if two amplifiers have the same music power, we may then

compare continuous power ratings.

This is important. Viewing music power rating as the secondary figure, we are

tempted to conclude that a bigger difference between the two numbers represents

a better amplifier. Our intuition favors the amplifier with better power-supply

regulation, so we suspect the whole notion of music power rating.

But starting on the other foot, with music power rating as the primary figure

and continuous power rating secondary, our intuition supports the rating inference.

It is legitimate, to get reasonable quality at low cost, to put music power ahead

of continuous power, by using an inexpensive power supply. But using a better power

supply results in an amplifier with "more solid" quality.

We would not say music power rating completely solves the problem of providing

a relative evaluation of an amplifier, though. Properly used, it is a good step

forward but there are still many things the present method of specifying performance

doesn't tell. Let's put it this way:

Provided the amplifier does not handle musical transients in some peculiar fashion

the specification does not show, and provided you always work it so musical peaks

never exceed twice the rated music power output, this rating does give a relative

indication of how much power amplifiers will deliver.

We can still have amplifiers that do strange things on certain kinds of musical

sound. None of the figures currently published shows what is likely to happen if

a momentary peak overshoots the peak music power (twice the music power rating).

One amplifier may handle these things without "batting an eyelid," while another

has electronic convulsions. That the specs do not tell us even now. This difference

can often account for one amplifier seeming to give a lot more undistorted power

than another of the same or similar rating, even when both the ratings are fully

supported by tests.

We still have the effect that loudspeaker loads can have on an amplifier, as

compared with the "dummy" resistance load, used for testing. The low distortion

figures are always obtained with the dummy load. Nobody publishes, even if he measures,

distortion with a loudspeaker load, because this depends, in an amplifier, on how

much reactance the loudspeaker has - and no two loudspeakers are alike.

A good amplifier may give up to twice the test distortion when a loudspeaker

is connected. A poor one may give many times as much distortion as soon as a little

reactance enters the picture.

It should be possible, for the benefit of those who really care, to find a standard

means of evaluating these various differences. It would be good to see the manufacturers

make a move, possibly through the IHFM, in this direction. Meanwhile, it remains

true that the specifications are a good starting point in judging an amplifier:

but the real test is how it performs in your system.

References

1. Crowhurst, Norman H.: "Why Do Amplifiers Sound Different?", Radio & Television

News, March, 1957.

2. Crowhurst, Norman H.: "Some Defects in Amplifier Performance Not Covered by

Standard Specifications," Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, October, 1957.

3. Van Recklinghausen, D. R.: "Mismatch Between Power Amplifiers and Loudspeaker

Loads," Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, October, 1958.

4. Crowhurst, Norman H.: "The Amplifier Distortion. Story," Audio, April and

May 1959.

Posted June 14, 2022

(updated from original post on 3/7/2014)

|