Note: U.S. Government documents are in the public domain and

may be freely distributed so long as content is not changed. This "A

Brief History of Atomic Clocks" document is being made available for the convenience

of RF Cafe visitors.

Those of us born in the 1950s and later have for our lifetimes been familiar

with atomic clocks and the incredible accuracy they provide for science experiments

and physical standards. A 1957 issue of

Scientific American

magazine published an article on the newfangled devices, and discussed the ammonia-based

and cesium-based types. The National Bureau of Standards' (now NIST) first atomic

clock used an ammonia molecule

(NH3) with the nitrogen atom back and forth within a triangular hydrogen

base at a frequency of 23,870 MHz (23.870 GHz). The current NIST time

service can be accessed at www.time.com. One of

the displays reports the time error of you computer, cellphone, watch, or however

you log on. Their latest publication is entitled, "A New

Era for Atomic Clocks," which reports on the newest timekeeper - the

NIST-F2, a cesium clock. "NIST-F2 would neither gain nor lose one second in

about 300 million years, making it about three times as accurate as NIST-F1, which

has served as the standard since 1999."

A Brief History of Atomic Clocks

-

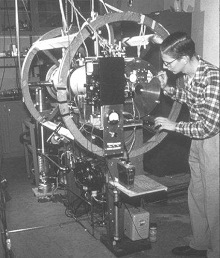

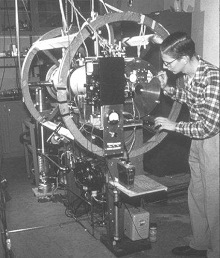

Isidor Rabi, a physics professor at Columbia University, works

on his atomic clock invention.

NBS-1 cesium-based atomic clock.

NBS-4 cesium atomic clock.

NBS-6 cesium atomic clock.

NBS-7 cesium atomic clock achieves an uncertainty of 5 x 10-15

.

1945 -- Isidor Rabi, a physics professor at Columbia University, suggests a clock

could be made from a technique he developed in the 1930's called atomic beam magnetic

resonance.

- 1949 -- Using Rabi's technique, NIST (then the National Bureau of Standards)

announces the world's first atomic clock using the ammonia molecule as the source

of vibrations.

- 1952 -- NIST announces the first atomic clock using cesium atoms as the vibration

source. This clock is named NBS-1.

- 1954 -- NBS-1 is moved to NIST's new laboratories in Boulder, Colo.

- 1955 --The National Physical Laboratory in England builds the first cesium-beam

clock used as a calibration source.

- 1958 -- Commercial cesium clocks become available, costing $20,000 each.

- 1960 -- NBS-2 is inaugurated in Boulder; it can run for long periods unattended

and is used to calibrate secondary standards.

- 1963 -- The search for a clock with improved accuracy and stability results

in NBS-3.

- 1967 -- The 13th General Conference on Weights and Measures defines the second

on the basis of vibrations of the cesium atom; the world's timekeeping system no

longer has an astronomical basis.

- 1968 -- NBS-4, the world's most stable cesium clock, is completed. This clock

was used into the 1990s as part of the NIST time system.

- 1972 -- NBS-5, an advanced cesium beam device, is completed and serves as the

primary standard.

- 1975 -- NBS-6 begins operation; an outgrowth of NBS-5, it is one of the world's

most accurate atomic clocks, neither gaining nor losing one second in 300,000 years.

- 1989 -- The Nobel Prize in Physics is awarded to three researchers -- Norman

Ramsey of Harvard University, Hans Dehmelt of the University of Washington and Wolfgang

Paul of the University of Bonn -- for their work in the development of atomic clocks.

NIST's work is cited as advancing their earlier research.

- 1993 -- NIST-7 comes on line; eventually, it achieves an uncertainty of 5 parts

in 10 to the 15th power, or 20 times more accurate than NBS-6.

- 1999 -- NIST-F1 begins operation with an uncertainty of 1.7 parts in 10 to the

15th power, or accuracy to about one second in 20 million years, making it the most

accurate clock ever made (a distinction shared with a similar standard in Paris).

Why Are Cesium Atomic Clocks Used?

Since 1967, the International System of Units (SI) has defined the second as

the period equal to 9,192,631,770 cycles of the radiation which corresponds to the

transition between two energy levels of the ground state of the Cesium-133 atom.

This definition makes the cesium oscillator (sometimes referred to generically as

an atomic clock) the primary standard for time and frequency measurements. Other

physical quantities, like the volt and meter, also rely on the definition of the

second as part of their own definitions.

Atomic clocks are quite complex, but the basic theory is simple. Like all clocks,

they are intended to make the same event happen over and over. The repetition of

this event produces a frequency, which is intended to be as stable as possible.

For example, the pendulum in a grandfather clock swings back and forth at the same

rate, over and over. The swings of the pendulum are counted to keep time. In a cesium

oscillator, the transitions of the cesium atom as it moves back and forth between

two energy levels are counted to keep time. The best cesium oscillators (such as

NIST-F1) can produce frequency with an uncertainty of about 1 x 10-15, which translates

to a time error of about 0.1 nanoseconds per day.

Why Must Time Be Measured So Precisely?

Precise time synchronization has many uses in everyday life. Synchronization

between two or more locations is necessary for high speed communication systems,

synchronizing television feeds, calculating bank transfers, and transmitting everything

from email to sonar signals in a submarine. Power companies use precise time to

regulate power system grids and reduce power losses. Radio and television stations

require both precise time-of-day and frequency in order to broadcast programs.

Precise time measurements are also essential for accurate navigation and the

support of communications on earth and in space. Scientific organizations such as

NASA depend on reliable and consistent time measurement for projects such as interplanetary

space travel. Fractional disparities in times between a space probe and tracking

stations on Earth can dramatically affect the positions of spacecraft. Precise time

measurements are also essential to radio navigation systems like the Global Positioning

System (GPS). By synchronizing the satellite clocks within nanoseconds of each other,

it makes it possible for a receiver to know its position on earth within a few meters.

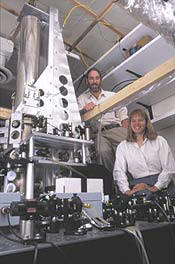

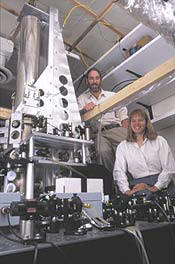

NIST-F1 Cesium Fountain Clock -

High-Accuracy Timekeeping

NIST-F1 Cesium Fountain Clock with Developers Steve Jefferts

and Dawn Meekhof

Who Needs High-Accuracy Timekeeping and Why?

High-accuracy timekeeping is critical to a number of important systems, including

telecommunications systems that require synchronization to better than 100 billionths

of a second and satellite navigation systems such as the Defense Department's Global

Positioning System where billionths of a second are significant. Electrical power

companies use synchronized systems to accurately determine the location of faults

(for example, lightning damage) when they occur and to control the stability of

their distribution systems. In the domain of space exploration, radio observations

of distant objects in the universe, made by widely separated receivers in a process

called long-baseline interferometry, require exceedingly good atomic reference clocks.

And navigation of probes within our solar system depends critically on well-synchronized

control stations on earth.

Time is also important in the ordering of many human activities including the

activities of financial markets. Time/date stamps are used to identify transactions

so that these can be placed in order, a process that is becoming increasingly important

as commerce moves electronically at faster and faster speeds. The need for good

timing in this area is emphasized by a recent Securities and Exchange Commission-approved

rule of the National Association of Securities Dealers that requires all member

brokers synchronize their time stamps to NIST.

The time-related quantity called frequency, basically the rate at which a clock

runs, is needed by the radio and television broadcast industry to maintain proper

control of transmissions and thus avoid interference between stations. Frequency

is also the basis for many electronic systems such as event counters, and many physical

quantities such as length, voltage, pressure, and so on are often transformed to

frequency, since frequency is a quantity that can be measured with very high precision.

How Does NIST Support These High-Technology Requirements?

The most fundamental way in which NIST supports such commercial activities is

through its traditional role in providing the very accurate measurements needed

to assure that specifications of high-technology equipment can be trusted. In fact,

most countries would not accept United States high-technology exports without a

guarantee that the specifications for this equipment are based on measurements that

are traceable to NIST, which must then be sure that these measurements are compatible

with those of the rest of the world. So, one key use of this new standard is to

serve as a reference for supporting specifications for equipment manufactured in

this country.

Beyond this fundamental mission role, NIST works to distribute timing signals

to a wide range of users through the Internet, by telephone, through radio broadcast

signals, and by means of very precise signals distributed by satellite. The usage

of NIST's Internet Time Service, now receiving more than 500 million calls per year,

is growing extremely rapidly. Radio time broadcasts from stations WWV and WWVB are

used to set a large number of clocks; in fact, there is a growing list of consumer

products (desk clocks, wristwatches, etc.) that use these radio broadcasts to maintain

accurate time and even handle daylight saving time changes automatically. At the

highest level of accuracy, NIST supports scientific studies, the space program and

the development of advanced timing equipment by delivering timing signals using

satellite transfer methods.

How Does NIST Disseminate Its Time and Frequency Information?

The oldest service is radio station WWV, near Fort Collins, Colo. It can be received

all over the world and broadcasts at 2.5, 5, 10, 15 and 20 megahertz on the short

wave band. A sister station, WWVH, broadcasts to the Pacific basin from Kauai, Hawaii,

on everything but the 20 megahertz frequency. The broadcasts include standard frequencies

and time intervals, the time (both voice and digital code), astronomical time corrections,

and public service announcements such as marine weather, geophysical alerts and

radio propagation information. The accuracy of these broadcasts, as received, is

between one and 100 milliseconds, depending on the distance to the receiver. A telephone

time service, which carries the WWV broadcast, is available by dialing (303) 499-7111

(a toll call outside the Denver Metro area). WWV has been broadcasting since 1923.

Another NIST radio station, WWVB, broadcasts a digital time code at the standard

frequency of 60 kilohertz. Also located near Fort Collins, this low frequency station,

which covers the continental U.S., has an accuracy for time comparison of between

0.1 and one millisecond. Its 60 kilohertz carrier frequency can be used for frequency

calibrations with an accuracy of better than 1 part in 100 billion.

The

Automated Computer Time Service (ACTS) provides millisecond accuracy for computer

clocks and other digital systems using dial-up telephone lines. This service includes

automatic compensation for telephone-line delay and advance notices of changes to

and from daylight savings time as well as leap seconds. NIST's time signals also

are available on the Internet. A visual display of the correct time can be seen

at www.time.gov, a service provided jointly

with the U.S. Naval Observatory.

NIST time can also be obtained via the Internet to set the internal clocks of

computers automatically, using free software available at

https://web.archive.org/web/20000511234748/https://www.bldrdoc.gov/timefreq/service/nts.htm.

NIST also disseminates time code information via satellite, utilizing two of

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's GOES weather satellites. The

coverage includes North and South America plus portions of the Atlantic and Pacific

oceans. This digital time code is accurate to within 100 microseconds, depending

on knowledge of the position of the satellite.

Posted July 15, 2021

(updated from original post on 7/1/2005)

|