|

March 1971 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

"Praetersonic" - now that's

a word you don't run up against very often. It is a combination of

praeter* (beyond)

and sonic (related to sounds), or what more familiarly is called ultrasonic. If

fact, praetersonics was the early term given to surface acoustic wave (SAW) piezoelectric

devices. Amazingly, even as far back as the early 1970s, SAW filters were being

fabricated that worked in the 40 MHz realm. This 1971 Popular Electronics

article does a really nice job of introducing the basics of SAW and BAW (bulk acoustic

wave) technology at the time it was coming into the mainstream. Lots of hurdles

still needed to be overcome, like high insertion loss, difficult to control impedances

and internal signal reflections, etc. As with many new technologies, pundits cast

hopeful prediction for having possibly found the panacea for many of the days' current

problems. To wit, "Acoustic-wave devices may finally hold the key to flat-screen

TV." One thing for sure is that it is hard to imagine what our cellphones and other

wireless devices would look like - or if they would even exist - without SAW and

BAW filters and resonators.

* Also written as "preter."

New Acoustoelectronic Components Replace Conventional Tuned Circuits

By James R. Fisk, W1DTY By James R. Fisk, W1DTY

Within 3 years a wholly new technology has been quietly developed that may lead

to the perfection of flat-screen TV, faster computers, better i-f strips, improved

radar filters, etc. This is a report on what has been referred to as the "most significant

development" since the transistor. The devices involve acoustic waves traveling

on the surface of piezoelectric substrates.

There is a broad interface between the sciences of acoustics and electronics.

While most people think this mingling is in the area of voice radio communications

and stereo sound reproduction, laboratories are quietly developing a brand-new acoustoelectronic

component - the surface-wave filter and amplifier. Recent advances promise that

the impact on the design of electronic equipment will be equivalent to that of solid-state

components.

The new technology goes by a variety of names: praetersonics (meaning beyond

sonics), acoustoelectronic, surface waves, etc.; but it involves nothing more complex

than honest-to-goodness acoustic waves travelling on the surface of miniature chips

of piezoelectric substrates.

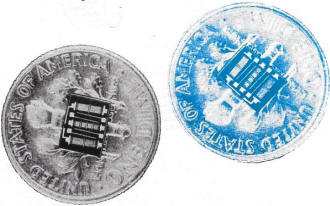

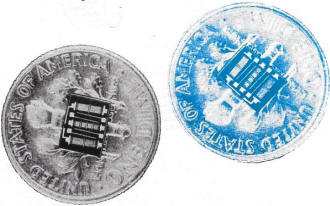

One company - Zenith Radio Corp. - has already

developed acoustic-wave 40-MHz i-f filters for color TV. They are only 0.15 in.

square and can be cascaded to synthesize the proper i-f response for color TV signals.

Aside from small size, the filters have the advantage of being permanently tuned.

Once set, they cannot drift off frequency. One company - Zenith Radio Corp. - has already

developed acoustic-wave 40-MHz i-f filters for color TV. They are only 0.15 in.

square and can be cascaded to synthesize the proper i-f response for color TV signals.

Aside from small size, the filters have the advantage of being permanently tuned.

Once set, they cannot drift off frequency.

In other laboratory experiments with praetersonics, high-gain r-f amplifiers,

oscillators, resonators, signal couplers, waveguides and delay lines are being developed.

Electronic navigation and communications systems employ complex signals that

must be rapidly processed and analyzed. Delay lines are essential to this process

since they can store the signals and compress, expand, or decode their waveforms.

These functions are usually handled by lengths of strip line or coaxial cable which

add bulk, are inefficient, and often introduce losses. However, praetersonic delay

lines - the first practical application of acoustic-wave technology - offer a compact

way of obtaining lossless, undistorted delays up to many microseconds duration,

with easy access to the signal for processing anywhere along its travel.

Actually, the first acoustic-wave delay lines employed bulk acoustic waves traveling

through the interior of a piezoelectric crystal.

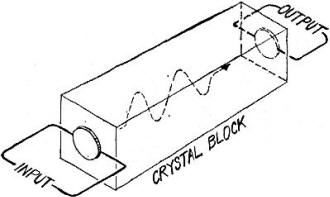

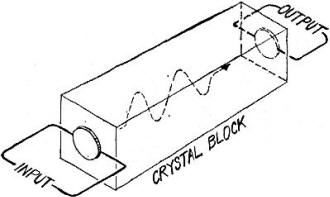

In its simplest form (see Fig. 1), the bulk system has a pair of transducers

mounted on opposite ends of a crystal. The input transducer, excited by an r-f signal,

beams acoustic energy through the crystal. The output transducer picks up the energy

and converts it into a usable electrical signal. The delay is simply the time the

signal remains in the block.

Bulk delay lines have one major disadvantage: it is almost impossible to tap

or otherwise manipulate the signal while it is in the crystal block. Surface acoustic

waves, signals that travel on the surface of the crystal instead of through the

crystal block, do not suffer from this shortcoming. The signal can be sampled anywhere

along its travel, after any duration, and the delayed waveform will be identical

to the input waveform.

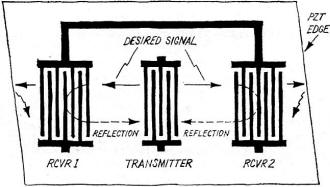

Fig. 1 - Early acoustic-wave delay lines employed bulk acoustic

waves which traveled through interior of crystal block from input to output transducer.

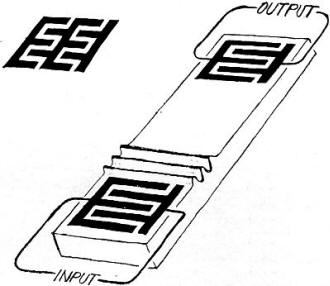

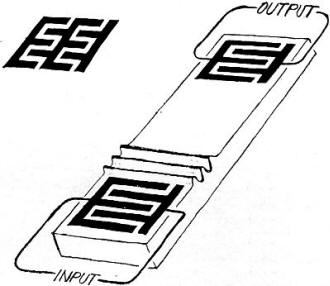

Fig. 2 - Modern praetersonic devices have interdigital transducers

which translate electrical input signals into physical waves (shown greatly exaggerated)

which travel along surface of crystals. Numerous impedances can be obtained by subdividing

interdigital electrodes as shown at upper left.

Fig. 3 - Curves of conventional LC tuned circuits and praetersonics

devices are basically similar.

Fig. 4 - Equivalent circuit of interdigital transducer is

a series resistance-capacitance network.

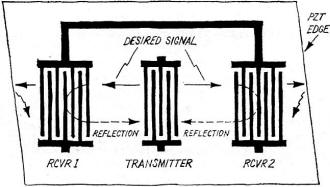

Fig. 5 - To reduce losses and minimize echoes, two receiver

transducers are used and substrate edges are cut at angles.

The basic surface-wave device is the delay line shown in Fig. 2. It consists

of a piezo-electric substrate (such as quartz) and input and output transducers.

The input transducer is an "antenna" which converts the electrical signal into an

acoustic wave which travels on the surface of tae substrate. At the other end of

the crystal, the wave is converted back into an electrical signal by the output

transducer.

The wave propagates rather slowly across the surface of the substrate, the delay

being determined by the spacing between the transducers. A 1-inch spacing corresponds

to a delay of about 8 microseconds.*

The design of the input and output transducers is extremely important since the

mass and shape of the electrodes have loading effects which influence efficiency.

The size of the transducer also affects bandwidth. The interdigital structure consists

of two separate arrays of metal electrodes resembling interlaced fingers.

The r-f signal across the input transducer interacts with the piezoelectric substrate

on the surface of the crystal, in opposite directions and at right angles to the

electrodes. Since the acoustic wave receives an in-phase energy boost at each electrode,

the wave generated by one finger pair builds up maximum acoustic power as it travels

through succeeding finger pairs.

The interdigital transducer functions with relatively low loss over a wide dynamic

range. By changing the number of fingers, the bandwidth can be tailored for nearly

any application. Finger size and spacing determine the center frequency. So the

basic acoustic-wave delay line becomes a resonator that can be substituted for LC

tuned circuits. The response curves for a typical surface-wave resonator and a typical

LC tuned circuit are shown in Fig. 3. The curves are basically similar.

The only significant difference between the simple delay line shown in Fig. 2

and a resonator is the spacing between the input and output transducers. In the

surface-wave resonator, the transducers are relatively close together (about 0.05"

in the 40-MHz i-f filters made by Zenith).

The input impedance of the surface-wave device is determined by the number of

electrode fingers and the length of the pattern. Also, a considerable impedance

range is available by subdividing the electrode pattern (see Fig. 2 upper left).

In practice, for the PZT material (lead zirconate titanate) used by Zenith, impedances

between 20 and 1000 ohms are easily obtainable at 40 MHz.

The equivalent circuit of an interdigital transducer is a series resistance-capacitance-reactance

network as shown in Fig. 4. In the diagram, Ra is the radiation resistance,

Xa is the radiation reactance, and Ct is the transducer capacitance. Inductance

L in the matching network compensates for Ct at the frequency of maximum response.

This inductance reduces mismatch losses and has an influence on the shape of the

passband.

In general, the tuning coil increases bandwidth. Tuning it slightly off the frequency

of maximum response skews the curve of the passband. This factor can be used to

advantage when tailoring the passband to a specific requirement, such as the video

i-f of a color TV receiver.

The interdigital transducer generates acoustic power that radiates in two directions.

Hence, the transducers inherently have at least 6 dB insertion loss since half the

power is radiated in the wrong direction. Also, if not properly terminated, this

backwave can be reflected at the edge of the substrate into the delay line where

it might show up as a spurious signal in the output.

To avoid the echo created by the backwave, wax is often deposited on the substrate

edge to absorb the backwave energy or the surface is etched behind the transducer

to scatter the backwave. Zenith cuts the substrate at an angle so that reflection

of the backwave is away from the active surface of the resonator.

In addition to backwave losses, a sizable portion of the signal arriving at the

output transducer is reflected back to the input transducer, where it is again reflected.

Each reflection results in a 6-dB drop in power level. This spurious echo, called

the triple-transit signal, is seen at the output 12 dB below the original signal

which made the trip only once. In the surface-wave i-f filter, this delayed and

attenuated replica of the original signal manifests itself as a ghost on the TV

screen.

Because the acoustic surface is not 100% efficient, there are transmission losses

that must also be added to the losses created by the echo signals. Therefore, total

losses can add up to 15 dB with tuning coils and 21 dB without the coils. A 3-dB

reduction in these figures can be obtained by employing the double receiving pattern

illustrated in Fig. 5, decreasing total insertion loss by lowering the directional

loss of the backwave.

In Zenith's i-f filters, careful design, including the use of shield lines between

transducers, has been successful in keeping reflections 30 dB below the desired

signal. This appears adequate for color TV i-f strips.

Aside from passband shaping provided by the external tuning coil, the response

can be broadened by increasing the terminating impedance. These two variables arc

used by the designer to shape the response curve to a given application.

Three cascaded surface-wave resonators provide the required response curve for

TV video in the Zenith filters. The connections between the resonators are shown

in Fig. 6. Resonator A provides out-of-band rejection and moderate attenuation

of the sound carrier. Resonators Band C provide a video notch at 41.25 MHz and,

with resonator A, provide the proper passband, including a notch at 47.25 MHz. Resonators

A and D work together to provide the proper level between the sound and picture

carriers.

Fig. 6 - Filter hookup for TV i-f strip and audio i-f take-off

is shown at top. Directly above, waveform produced by filters (dashed line) is shown

superimposed on desired wave shape.

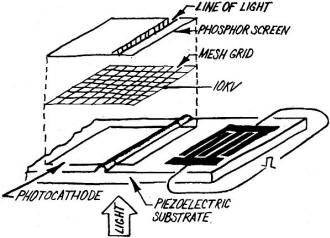

Fig. 7 - Integral amplification from acoustic wave devices

is obtained from addition of a chip of n-type semiconductor material mounted over

substrate.

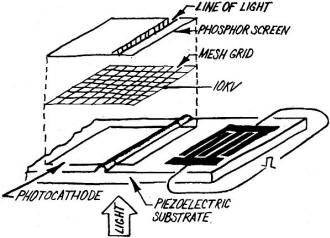

Fig. 8 - Acoustic-wave devices may finally hold the key

to flat-screen TV. In illustration, surface wave stimulates emission from photocathode.

Emitted electrons pass through B+ boosted grid and are accelerated to produce light

on a phosphor screen.

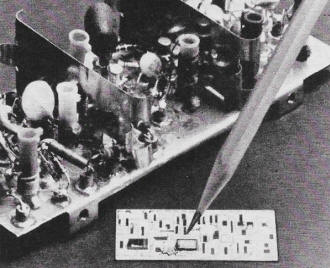

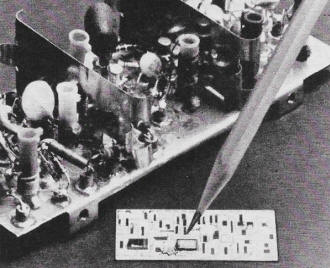

Zenith's thick-film circuit (foreground) is designed to replace

modern bulky i-f strips (background). Ultrasonic filter at pencil tip will reject

frequencies other than those desired.

The measured video response obtained by cascading the three surface-wave resonators

comes very close to fulfilling the desired color-TV i-f response as shown. It ran

be seen that the praetersonic surface wave filter provides the required passband

as well as the necessary traps at the desired locations.

When the praetersonic i-f filter was substituted for a standard tuned-circuit

i-f strip in a Zenith color TV receiver, it produced a picture of good quality with

no noticeable ghosting. The amplifiers used with the experimental filter were of

the wideband variety with at least a 60-MHz bandwidth.

Although the experimental Zenith filters used fairly conventional solid-state

amplifiers, future designs will probably incorporate a surface-wave amplifier that

is an integral part of the resonator. For useful praetersonic amplification, the

piezoelectric characteristics of the substrate should be separated from its semiconductor

properties. Since the electric field associated with an acoustic surface wave extends

out of the surface of the crystal, it can interact with the electrons in a de-powered

semiconductor placed a small distance above the crystal as shown in Fig. 7.

The basic items for the surface-wave amplifier are an optically flat piezoelectric

crystal and an n-type silicon semiconductor. Amplification results from the interaction

between drifting electrons in the n-type silicon and the piezoelectric field in

the surface-wave device. For minimum signal distortion, the two crystals must be

acoustically separated.

But for maximum field-electron interaction, the air gap must be a small fraction

of the acoustic wavelength. In a typical 100-MHz praetersonic amplifier, an air

gap of about 200 millionths of an inch is used. This spacing can be obtained by

a layer of silicon-dioxide that has been vacuum-deposited on the surface of the

substrate.

Since the piece of n-type silicon is fairly large, it has high resistivity and

requires a 2000-volt power supply for high gain. If the silicon is made very thin

and broken into segments, however, 30 dB of gain is possible with a 180-volt supply.

By adjusting the supply voltage, this system can provide either gain or attenuation,

allowing the output signal a range in excess of 100 B. When the applied voltage

is low, the surface wave is attenuated because energy flows from it to the slower

moving electrons in the semiconductor. As the voltage increases beyond the point

where electrons are moving faster than the surface wave, energy is imparted to the

wave, resulting in gain.

The surface-wave amplifier has a built-in bonus. Reflections between the input

and output transducers are attenuated so that the triple-transit signal is greater

than 60 dB down from the desired signal. And the high-gain flexibility means that

switches and modulators with greater than 90 dB of dynamic range are possible.

The acoustoelectronic amplifier can perform many other functions besides variable

amplification. If the amplifier is operated in its nonlinear saturated region, it

functions as an effective r-f mixer. Using external feedback, stable oscillation

results. It is feasible to conceive a 500-MHz amplifier, mixer, and low-frequency

i-f strip all operating on a single substrate.

With the arrival on the scene of the acoustoelectronic amplifier, it appears

that conventional tuned LC systems have a serious competitor, at least in the frequency

range from 30 to 500 MHz.

Looking into the future, praetersonics may hold the key to flat-screen TV picture

tubes if current development work pans out. The basic principle for the flat screen

is shown in Fig. 8. The electric field between crests of an acoustic surface

wave is sufficient to control emission from a semiconductor photocathode. To use

this voltage, a photo-emissive material is deposited on the piezoelectric substrate.

When suitably lighted, the photocathode emits electrons which are accelerated by

a 10,000-volt field to produce visible light on a phosphor screen.

An input pulse produces a transverse line of light that moves across the phosphor

screen, providing the horizontal scan. Vertical scan can be obtained. with another

acoustic beam applied simultaneously at right angles to the first beam.

Surface acoustic waves also have potential applications in high-speed data processing

with bit rates in excess of 100 MHz. In this scheme, digital-logic bits in the form

of acoustic pulses pass through an arrangement of transducers which perform the

logic operations by providing outputs of zero or high-amplitude pulses. These acoustic

wave pulses are then converted into pulsed r-f waveforms for further processing

by an output gate circuit.

Logic inverters and NAND and OR gates have already been operated at 120 MHz with

a 5-MHz bit rate. And 100-MHz bit rates are anticipated shortly.

Another important application of praetersonics is in the field of high-resolution

radar. Current radar displays employ bandwidths of less than 10 MHz. But for high

resolution, bandwidths should be on the order of 500 MHz. Broadband praetersonic

delay lines can be used between the radar and the display to store and recirculate

the signals so that they can be sampled and displayed at the lower frequency.

Since the acoustic wavelength is so much

smaller than the free-space wavelength, many signal-processing techniques that have

been previously confined to the microwave region can now be translated to the lower

frequencies. Acoustic waveguides operating at 5 MHz are possible, as well as are

strip-line-type directional couplers and other hardware familiar to the microwave

technician. A lab-built directional coupler for 5 MHz, for example, provides up

to 20 dB of isolation and its total length is only 6 inches. Since the acoustic wavelength is so much

smaller than the free-space wavelength, many signal-processing techniques that have

been previously confined to the microwave region can now be translated to the lower

frequencies. Acoustic waveguides operating at 5 MHz are possible, as well as are

strip-line-type directional couplers and other hardware familiar to the microwave

technician. A lab-built directional coupler for 5 MHz, for example, provides up

to 20 dB of isolation and its total length is only 6 inches.

Although praetersonics is a new technology, it has evolved from theory to practical

hardware in less than three years. It is difficult to tell if we can expect the

same rate of progress in the future, but praetersonics promises to have at least

as much impact on electronic circuitry as did the introduction of the transistor.

It is now only a matter of time before this prediction becomes reality. Both waveforms

are basically similar.

* Until recently, praetersonics was known as "microwave acoustics" due in part

to the fact that early work in the field concentrated on devices for VHF and microwave

applications. But the term "micro" is also associated with the micron wavelength

of an acoustic wave on the surface of a piezoelectric crystal. At 30 MHz, for example,

a 100 micron or 0.004" wavelength is possible because acoustic waves travel 100,000

times slower than do radio waves!

|