|

March 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Author Len Buckwalter states

in this 1972 "Communications Satellites" article from Popular Electronics

magazine that at the time, radio channels were so crowded in California that police

were using spectrum in the television broadcast band for communication. The FCC

was denying recreational boaters channel space on favor of commercial operators.

The problem could not be blamed on available frequency space, but rather on the

lack of inexpensive electronic components that worked above a kHz or so. Nowadays

when you read in the news about such desperate need of spectrum that network owners

pay millions or billions of dollars for a few measly MHz of bandwidth, the cause

is truly an overabundance of devices vying for space. Although truthfully, you could

claim that exactly the same scenario is playing out today while semiconductor companies

strive to bring low cost components in the millimeter wave bands above 30 GHz.

These Radio Relays in the Sky Are Helping Us Cope with Today's

Communications Explosion

By Len Buckwalter

Whether you are a ham operator, telephone dialer, airline pilot, police dispatcher,

computer operator, shortwave listener, or anyone who wants to exchange information

by wire or radio, you're aware of a world in the midst of a communications explosion.

Phone circuits are often clogged, radio frequencies are so congested that police

in California speak over TV channels, and boat owners are forced to abandon some

of their bands to commercial mariners. A million CB'ers seek more channels for personal

talk and air traffic controllers urgently need data links to keep aircraft safely

apart.

Long-range planners insist that these distressing

symptoms only hint of what's to come. By the end of this decade, they see a whopping

500 percent increase in global communications. They predict the sound of human voices

on phone lines will soon be exceeded by the chatter of machines conversing with

each other. And the intense pressure to communicate can only increase as developing

nations emerge, or as new electronic services are brought into the home. Long-range planners insist that these distressing

symptoms only hint of what's to come. By the end of this decade, they see a whopping

500 percent increase in global communications. They predict the sound of human voices

on phone lines will soon be exceeded by the chatter of machines conversing with

each other. And the intense pressure to communicate can only increase as developing

nations emerge, or as new electronic services are brought into the home.

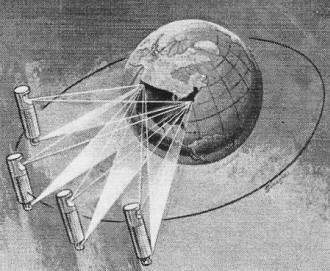

But thanks to the communications satellite, there should be more room for everyone.

Today, a single space vehicle can carry more traffic than all the transatlantic

undersea cables combined. Merely three satellites deployed about the earth can "see"

every point on the globe, and join any two of them as no cable can. Besides international

coverage, a rising generation of "domestic" satellites is filling in sparsely populated

regions. This is about to happen in the northern wilderness where cables are costly

to lay. Canada has agreed to pay the U. S. $30 million for launching three satellites

in 1972, with a similar system planned for Alaska. These developments make it nearly

incomprehensible that the first commercial communications satellite thundered off

Cape Kennedy only seven short years ago.

Marconi Bridged the Ocean. The concept of a "radio relay tower

in the sky" is often dated at 1945, but its genesis goes clear back to Marconi himself.

He had stumbled on the "passive reflector" idea when his signals bridged the ocean

in 1901. Although Marconi had no inkling why his signals crossed the Atlantic, it

mattered little at the time. The breakthrough was that long-haul communications

were finally freed from the wire. Until then, linking continents was done by the

ship Great Eastern which carried on long voyages mountainous stores of food and

equipment to lay cable on the ocean floor. It took two hours to merely lower the

30-ton cable to the bottom. After the job was completed, the system could carry

only a limited number of messages. (Even the most modern cable proposed today has

a capacity of only 840 telephone circuits.)

Marconi, on the other hand, had captured signals across the Atlantic on a kite,

a 600-foot aerial, coils, capacitors, an earphone and an inefficient detector. He

had unwittingly used nature's communications satellite, the ionosphere. This well-known

electrical mirror hovers near the top of the atmosphere where it intercepts radio

signals from the earth. If angles are correct, the signals are reflected downward

and return to the surface at some distant point. The phenomenon is curiously reminiscent

of the first generation of crude, passive communications satellites.

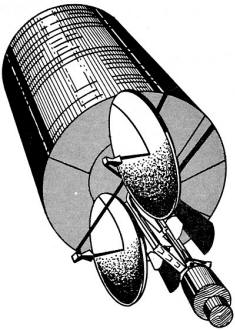

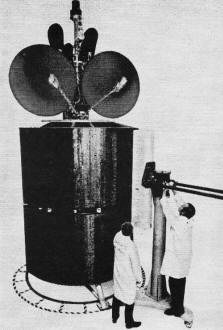

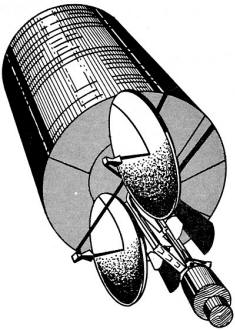

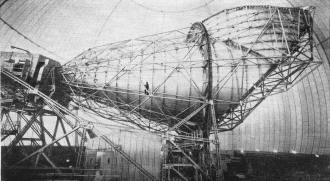

Intelsat IV satellite is shown here being tested in the Hughes

RF laboratory.

Besides achieving great distance, Marconi had produced a second miracle: tremendous

increase in bandwidth, a precious commodity in any communications medium. His experiments

soon led to the opening of a broad path for global communications and international

broadcasting between 3 and 30 MHz. This is the high-frequency band (HF) where the

ionospheric "skip" effect is most efficient. If a single voice message requires

a total bandwidth of 4 kHz, then consider that the entire shortwave region from

3 to 30 MHz will accommodate only about 7,000 messages. As any ham or SWL knows,

the actual capacity is much smaller because of fading, noise, solar flares, radio

blackouts and other caprices of the ionosphere. Nevertheless it provided the most

important transmission medium for the first half-century of global communications.

Today the ionosphere groans from overload. The ham who chases DX fights through

unbelievable interference; CB'ers suffer from the howl of heterodynes from local

and distant stations; and nations enter delicate negotiations to parcel out precious

frequencies. And the pressure increases as the nature of our communications demands

greater bandwidth than ever. A TV channel, for example, consumes a 6-MHz slice of

the spectrum. This alone gobbles up about 1500 voice circuits and makes international

TV a technical impracticality between 3 and 30 MHz.

Passive Reflectors. The first signs of relief appeared in 1946. Like Marconi

forty-five years earlier, experimenters wanted to exploit a natural reflector, only

now it was the moon. It was known that if a signal were high enough in frequency,

it would pass through the ionosphere in a straight line and be lost in space. Why

not, went the theory, use the moon as a passive reflector to return the signal?

The U.S. Army Signal Corps did just that when it swung a radar antenna toward the

lunar surface and fired a pulse of microwave energy. Slightly more than two seconds

later a weak, noisy signal returned and was heard in the receiver. It was powerful

evidence of the feasibility of a true communications satellite.

Suddenly an idea suggested a year earlier (1945) by a British science writer

no longer smacked of science fiction. Arthur C. Clarke (who wrote the film "2001"),

and others before him, had dreamed up a novel concept of artificial satellites orbiting

the earth to serve as radio relay stations. He calculated that a satellite circling

at a height of some 22,000 miles would seem to be fixed over a spot on the earth's

surface. At this altitude the satellite would take 24 hours to revolve once around

the planet. Since the earth also takes this time for one rotation, the satellite

would appear to remain in one position. This could provide an unrivalled platform

for retransmitting radio signals over the horizon. Clarke's predictions proved surprisingly

accurate.

By 1958 the U. S. Air Force launched the first true communications satellite.

Named Score, it was primitive by today's standards, its payload little more than

a tape recorder playing a Christmas greeting back to earth from orbit. (President

Eisenhower had pr-recorded the message on the ground.) The conventional batteries

that powered the satellite went dead in 12 days. (Today the power lasts seven years.)

But Score was hailed as the first "active" satellite because it didn't passively

bounce back signals to earth but contained active, powered circuits.

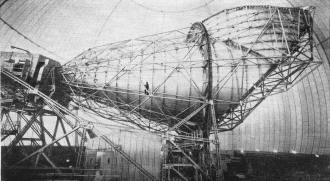

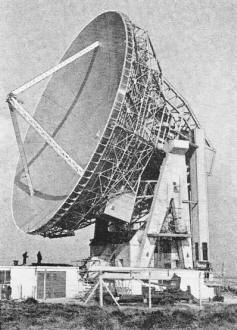

The big 380-ton horn antenna at the earth station at Andover,

Maine, is used by Comsat to transmit and receive satellite signals between U.S.

and Europe.

The heyday of the passive reflector came in 1959 when Bell Telephone Labs in

New Jersey communicated with colleagues in California during Project Moonbounce

(again using the moon.) This soon led to a manmade reflector called Echo. Launched

into orbit as a tiny packet, Echo reacted to the sun's rays by expanding into a

100-ft balloon with an aluminum foil skin. This created a metal surface orbiting

1000 miles aloft. Although it became wrinkled and deflated after three years, Echo

was used to refine the technology needed in the ground stations. During this period,

engineers developed horn-reflector antennas of great gain and directionality, extremely

low-noise receivers and new tracking techniques by computer. The passive reflector

idea, though, was short-lived.

A far more sophisticated package roared off the pad in 1960. Called Courier I-B,

it was studded with 20,000 solar cells and could sustain itself by converting the

sun's energy into electricity. Equipped with four receivers, four transmitters and

five tape recorders it demonstrated the possibility of storing received signals

on tape, then re-transmitting them at a later time. This was the solution to the

problem of linking two ground points that could not "see" the satellite at the same

time. Technical difficulties brought Courier to a premature end after 18 days, but

not until it had received and transmitted 118 million words.

Telstar and Later. Courier stirred great scientific interest

but it only hinted of things to come. A series of sensational successes followed

in the summer of 1962. Just before daybreak on a July morning a Thor-Delta rocket

lifted off Cape Kennedy. Minutes later Telstar I, a 3-foot-wide craft was inserted

into an orbit that ranged between 600 and 3,500 miles. During the sixth pass, Telstar

relayed the first live TV program between U.S.A. and Europe. It did it with no time

delay or tape storage: Telstar received and transmitted simultaneously. Below the

TV picture of singer Yves Montand appeared the sub-title on American home TV sets

"Live From France."

Despite its dazzling success, the vehicle fell victim to the hostile environment

of space. Two months after launch, engineers noted the vehicle was not executing

the "T2" command, an order to turn off communications equipment when out of range.

Otherwise there would be a serious drain on the electrical system. Some electronic

detective work revealed the culprit. Sensing devices on Telstar reported the space

vehicle had picked up 100 times more radiation than predicted as it skirted the

Van Allen Belt (which girdles the earth with high-energy electrons.) Acting on this

cue, engineers doused similar Telstar components in the lab with heavy radiation.

They discovered that radiation could penetrate transistor casings and ionize the

gas trapped within. Since gas ions are electrically charged, they interfered with

normal transistor action. Telstar I fell silent six months after launch.

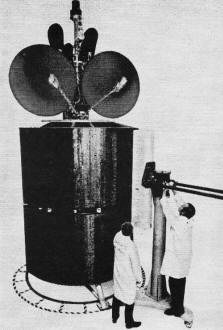

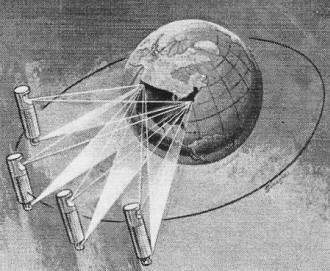

Four domestic satellites proposed by Bell System would provide

83,000 channels for voice, 24 TV, and 64 spares.

These findings protected Telstar II against similar misfortune. A new orbit swung

the vehicle 3000 miles further into space and held it beyond strong radiation belts

for longer periods. What's more, the troublesome gasses inside the transistors were

carefully evacuated during manufacture.

The stage was now set for the first practical, work-a-day communications satellite.

Much had been learned through experiments on these early "low-orbit" vehicles which

swept over the earth to link two points on the earth's surface only hours at a time.

Now the time had come for a satellite system that could provide continuous commercial

service. It happened April 6, 1965, as Early Bird (Intelsat I) rose to its perch

22,300 miles above the Atlantic. Small by today's standards (it weighed 8.5 lb.),

it had a capacity of 240 telephone circuits. But in a single leap it increased the

transatlantic cable capacity by 50 percent! It also turned in a remarkable record

of 100 percent reliability in 3 1/2 years of service.

Just as Clarke predicted back in 1945, Early Bird and the "synchronous" satellites

which followed give the illusion of standing still. Their velocity through space

is about 7000 mph, as the earth's surface below moves at 1000 mph. The reason for

the difference is easily seen by viewing a disc rotating on a phonograph. Although

the disc near the spindle seemingly crawls around, the edge of the record moves

quickly. Both areas, however, complete one turn in exactly the same time.

The satellite's synchronous orbit, which is also described as "geostationary,"

provides a big advantage in satellite communications. The craft is fixed s that

it becomes the equivalent of a permanent tower high above the earth. This is in

contrast to earlier satellites which rapidly looped around the globe to provide

only fleeting periods of communication. The synchronous craft "transponds" continuously;

that is, it receives signals from one earth station and relays them to another station

thousands of miles away at the same time. The shortcoming, though, is that a synchronous

satellite "sees" only one-third of the earth from its fixed position. This is solved

by orbiting three equally spaced satellites for global coverage. Right now there

are vehicles hovering above the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans to enshroud

the earth.

The synchronous satellites have other shortcomings, too. Remaining parked in

orbit is a tricky condition because celestial mechanics are hardly constant. The

earth's gravitational pull has irregularities which cause orbital drift. The sun

and moon exert pulls which affect the satellite with uneven forces. Even the tiny

push of sunlight against a space craft threatens to disrupt its delicate balance.

Such factors can wobble the vehicle off course and ultimately spin it to a fiery

death in the atmosphere. To see how these problems have been solved, let's examine

the techniques used in Intelsat IV, the newest of the communications satellites.

The Newest Satellite. The Intelsat IV was placed into service

in March, 1971 over the Atlantic. Any irregular force on the vehicle is countered

by pairs of onboard thrusters. Driven by hydrazine, the thrusters are positioned

around the vehicle so command signals from earth can accelerate it in any direction.

Sufficient propellant (270 lb) is stored to keep the craft on station during a design

life of seven years.

Next, there's the matter of keeping certain surfaces pointed earthward. This

is essential to exploit highly directional antennas which make most efficient use

of electrical and radio power. This is done by "Spin-stabilization" to keep the

vehicle rotating at 50 rpm. (Thrusters also regulate this action.) Thus the craft

achieves rigidity in space from a gyroscopic effect. Not all of the satellite is

allowed to spin since those directional antennas must be aimed and held with incredible

accuracy. About half the vehicle, the part with the antennas, is "despun," or counter-rotated,

to bring it to a halt with relation to earth. A transfer assembly on ball bearings

carries power and signals between the rotating halves of the vehicle.

This stable arrangement supports a veritable antenna farm. Two high-gain horns

receive signals from earth and two transmit them back There are several non-directional

antennas to handle the command and telemetry signals which monitor and govern the

vehicle's condition, There are also "spot beam" antennas which can be precisely

aimed at a small region on the earth for point-to-point traffic. These narrow signals

can increase the number of circuits since energy is held within a beam only 4.5

degrees wide.

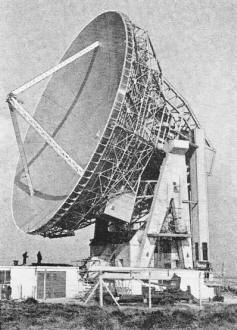

Ground station at Goonhilly Downs in Cornwall, England, uses

steerable 85' parabolic dish to transmit, receive.

Thanks to high-gain antennas in the satellite, as well as huge horns on the ground,

the transmitter power may be only six watts. In a typical transmission, a signal

from the ground is sent to the satellite on a frequency of approximately 6 gigahertz

(6,000 MHz). This is in the microwave spectrum where waves are extremely short in

length and display no bending through the ionosphere. Upon receiving the signal,

one of 12 transponders aboard the satellite retransmits the intelligence toward

earth on 4 gigahertz (4,000 MHz). By separating arriving and departing signals in

frequency, the relay is simultaneous, since the transmitter doesn't block the receiver.

Power for the satellite is derived from 40,000 solar cells which spin in the

sunlight. They produce about 500 watts of primary electrical power (at 24 volts)

to energize transponders and control systems. If a solar eclipse occurs, power is

temporarily obtained from two nickel-cadmium batteries held on charge by about 3000

solar cells. The complete, self-sustaining vehicle is about the weight of a Volkswagen.

What does it add up to in communications capacity? With its 12 transponders operating,

Intelsat IV can provide more than 9,000 two-way telephone circuits (each 4 kHz)

or 12 television channels. In typical operation the satellite carries about 5,000

voice channels and TV. Some transponders aboard feed the spot-beam antennas for

point-to-point traffic, while other transponders feed the horns which cover the

viewable earth disc. Compare Intelsat IV's capacity -a total bandwidth of 432 MHz

- with an ionosphere barely 30 MHz wide. And the satellite is virtually immune to

the vagaries of sun and static. During 1970, the Intelsat III satellite series carried

their traffic without fail during 99.55 percent of the time.

Support from the Ground. Orbiting hardware captures the headlines,

but it would be so much debris without support from earth stations. To gain access

to the system, 30 countries have erected 43 earth stations throughout the world.

These figures are expected to double within the next three years as space communications

continue to reduce traffic costs. It's notable that countries with traditionally

poor communications (Latin America, the Far East, the Near East and Africa) are

taking the great leap forward with the construction of their own earth stations

to participate in the system.

Consider what you'd see at a typical ground facility, like the Bartlett Earth

Station recently completed near Anchorage, Alaska. It communicates through Intelsat

III positioned over the Pacific to provide a direct tie between Alaska and the lower

48 states or Hawaii, Australia and Japan. The station receives locally generated

traffic (telephone, teletypewriter, TV or high-speed data) and sends it through

a huge dish-shaped antenna 98 feet in diameter. Although the array weighs 315 tons,

it can be rapidly rotated toward the satellite and zeroed on target with an accuracy

of 2/100ths of a degree. Signals fly simultaneously to and from the satellite through

the same dish, kept apart by a 2-gigahertz frequency difference. To keep ground

receivers operating at the greatest possible gain, front-end amplifiers are cooled

almost to absolute zero by helium. This slows the molecules in the circuit so they

contribute less noise to the faint signals arriving from above. It takes 16 men

to run Bartlett around the clock.

About 80 percent of the traffic now carried by all satellites is the telephone

message. And it's increasing at a rapid pace. The number of phone calls between

Argentina and the U.S. jumped from 200 to 400 per day last year when satellite service

commenced. TV news pickups and special events via live satellite relay are now routine,

and this will surely increase due to major rate reductions. Today's cost for a minute

of transatlantic TV is $66 - a mere 15 percent of the tariff back in 1965.

Despite the exciting success of the communications satellite, its future sparks

plenty of lively controversy. The privately owned Communications Satellite Corp.

(Comsat) in the U.S. is attempting to accommodate the differing needs of a common

carrier like A.T.&T. and the TV networks. A renewed space race is brewing between

three competing international systems: Intelsat, an organization of 79 nations in

a joint venture; the Franco-German Symphonie satellite and the Russian Molniya.

Technically, some interests are calling for a quick jump to much higher frequencies

- as far as 30,000 MHz - where the bandwidth available is even greater. This is

opposed by others who feel that the state of the art is still years behind such

a plan. They point out that, as the frequencies grow higher, they behave more like

light and are attenuated by rain and other obstacles. But it's a healthy battle

with little of the wasteful duplication of the first space race.

Posted January 31, 2024

(updated from original

post on 10/1/2017)

|