|

March 1973 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

According to author R.R. Freeland,

manufacturing processes for radio-quality manmade crystals saw major improvements toward

the end of World War II. At the time, the process was highly manual-intensive, as

can be seen in this really nicely done 1940s video titled "Crystals Go to War."

Prior to the use of crystals as frequency-determining devices, inductor-capacitor (LC)

tank circuits were the dominant configuration. There were actually other frequency-determining

schemes like spark gaps and even vibrating mechanical reeds. As you might guess, anything

less than a crystal suffered from higher short-term and long-term stability, drift over

temperature, microphonics,

and the phase noise

- composed of multiple effects like shot noise, i/f noise, etc. - was relatively terrible.

Crystals for CB & Ham Communication

To Keep Your Signals Steady as a Rock, You Need Quartz Crystals in Proper Circuits

By R. R. Freeland

President, International Crystal Manufacturing Co.

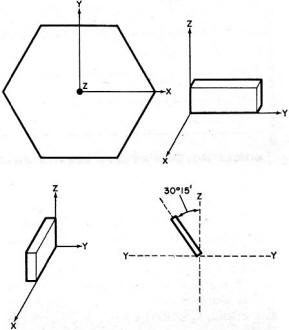

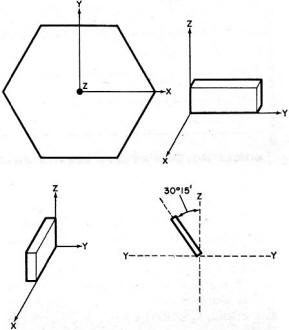

Fig. 1 - Axes for the mother quartz crystal. Both X-cut and Y-cut

blanks are shown. The AT-cut crystal is widely used.

Quartz crystalline material, natural and "grown" by man, has become the most widely

used device for controlling radio frequencies. Historically, crystal frequency control

began with radio amateurs back in the late 1920's. Full-scale production and use of crystals

in the commercial market began during World War II. Since 1945, however, considerable

effort has gone into improving crystal production methods and the circuits in which crystals

are used to provide close control over frequencies over wide temperature ranges.

Many crystals, particularly quartz, exhibit a property known as "piezoelectricity,"

whereby they convert mechanical energy into electrical vibrations (oscillations) and

vice-versa. A crystal blank cut from quartz will vibrate mechanically about one or more

nodal points when a voltage is applied to it. Both fundamental and harmonic (whole multiples

of the fundamental) oscillations are generated by the crystal.

The fundamental frequency at which a crystal is made to oscillate depends upon many

factors but mainly the crystal's size and thickness, the angle of "cut," and operating

temperature. As far as size and thickness are concerned, the smaller they are, the higher

will be the operating frequency. The cut of the crystal refers to the manner in which

the blank is sliced from the bulk crystal material, taking into account the six-sided

crystalline structure.

Of the general modes of oscillation obtainable from a crystal (extensional, shear,

and flexure), we are interested in only the shear mode for amateur radio and CB applications.

In this mode, wave propagation is parallel to the thickness dimension.

The thickness shear is sometimes called the high-frequency shear mode. The quartz

can also oscillate at a mechanical harmonic (must be an odd number) such that the two

opposite faces of the blank effectively move in opposite directions. The mechanical harmonic

should not be confused with the electrical harmonic which can be any multiple of the

fundamental frequency.

Fig. 2 - Edge-clamp or cemented-lead mount.

The orientation of the raw quartz crystal is universally defined by assigning X, Y,

and Z axes as shown in Fig. 1. The Z axis is commonly referred to as the "optical" axis

owing to the fact that it can be located by optical methods. No piezoelectric effects

are directly associated with it as they are with the X (electrical) and Y (mechanical)

axes. X-cut crystals are used mainly for low-frequency applications, and Y cuts are used

mainly for medium- and high-frequency applications. Hence, our only interest here is

in the various Y-cut crystals.

A simple Y-cut crystal is a poor frequency control device. So, the simple Y cut has

been replaced by rotated-Y cuts, the most common of which is the AT cut whose plane is

rotated around the X axis by approximately 35° from the Z axis. By carefully selecting

the angle of rotation, crystals with very small temperature coefficients can be fabricated.

For critical requirements, angle tolerances are maintained within 15 seconds of arc.

For less critical ham and CB applications, the tolerance can be within 3 minutes of arc.

The AT crystal is commonly mounted in its holder by the edge-clamp method (cemented

lead mount) as shown in Fig. 2. Plated electrodes cover part of the crystal face. Plating

on the opposite faces extends to the edges to provide good electrical contact. By keeping

the electrode area small, the capacitance is reduced and the principal activity is confined

to the central region of the crystal to improve stability. This, in turn, reduces the

impedance of the supporting wires.

High-quality piano wire supports the crystal. A small amount of conductive cement

assures a good connection between the wire and the plated electrode. (With the plated-wire

mounted crystal, calibration tolerances can be as high as 0.001 percent.) The crystal

is sealed in a vacuum or dry-nitrogen-filled glass or metal case.

Crystals are designed and processed to undergo a minimum of aging during their useful

lives. A 10-part-per-million rate the first year is not an unreasonable figure. The aging

rate decreases with time and usually levels off after about six months of operation.

Pre-aging by heat cycling can reduce the initial aging period.

When a crystal is put into operation, the lower the drive level, the longer its useful

life. The aging factors are more pronounced when a crystal is operated at high drive

levels, and the higher operating voltage increases the possibility of corona discharges

which, together with greater vibration amplitudes, can lead to crystal failure. To obtain

maximum life and stability, crystals should be operated at the lowest practicable drive

levels.

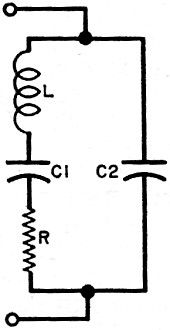

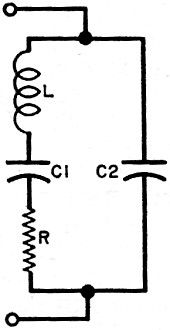

Fig. 3 - This is a simplified schematic of an equivalent circuit for

a typical quartz crystal mounted inside a holder.

Crystal Circuitry. The simplified equivalent circuit of a crystal

in its holder is illustrated in Fig. 3. Capacitor C2 represents the electrostatic capacitance

between the electrodes, while L, C1, and R represent the equivalent mass, compliance,

and frictional loss of the vibrating crystal. Capacitance C2 can be measured by conventional

methods; the series-resonant and anti-resonant impedances and frequencies can be measured

by using a crystal impedance meter. From these two sets of measurements, C1 and L can

be calculated. (The crystal can appear as either a low-impedance device at series resonance

or a high-impedance device at anti-resonance.)

Crystals can be operated at series resonance, but it is impractical to operate them

at exactly the anti-resonant frequency. Adjusted to operate at maximum voltage (parallel

resonance) at some proper phase and frequency, the crystal is most sensitive to frequency

changes with small changes in effective load impedance. Both the equivalent impedance

and resonant frequency change with effective load changes. A 30-to- 40-pF load operates

the crystal at a lower impedance point where small circuit changes have less effect and

the adjustment range is smaller with the same trimmer capacitor.

The total shunt capacitance across the crystal plays an important part in determining

the final frequency. However, the crystal itself bears the primary responsibility for

frequency stability, which is dependent upon the magnitude of the change in reactance

with frequency.

Crystal Performance. Crystals can be graded according to activity,

frequency stability, bandwidth, quality factor (Q), and parameter stability. Frequency

stability is the crystal's ability to minimize frequency changes arising from variations

in the parameters of the external circuit. Bandwidth is the useful operating frequency

range of the crystal. Quality factor is simply a figure of merit. Parameter stability

is the stability of the crystal parameters during changes in temperature, drive level,

and tuning adjustments. The stability of a crystal oscillator depends upon both the crystal

and the parameter stabilities.

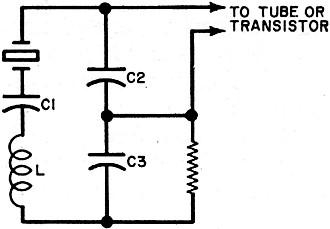

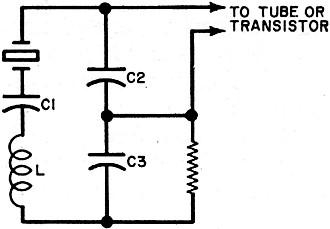

Fig. 4 - Typical crystal oscillator circuit.

Transmitter crystals are usually operated at the fundamental frequency into an approximate

32-pF load. A common crystal oscillator configuration is shown in Fig. 4. The maximum

effective load is present in this circuit when C1 is shorted. Inductor L is used to balance

out capacitive reactance to permit operating at series resonance.

Many CB rigs provide a single trimmer capacitor for all channels instead of individual

trimmers for each channel, which complicates correlation for many transmitters. Switch

lead lengths and dress, as well as component locations, affect the oscillator load capacitance.

Most of the CB transmitters that cover all 23 channels reduce the number of crystals

needed by combining several crystals to produce the desired frequencies and use the same

group for the receiver's oscillator. Two crystals must be considered for determining

the accuracy of the final signal frequency. Both crystals must track in tolerance over

the temperature range to yield the desired results. Not only does the crystal's temperature

characteristic become im-portant, but the exact oscillator load must also be known to

allow calibration.

Posted January 15, 2018

|