|

August 1956 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

The radar system I worked

on in the USAF used two early memory types described in this 1956 Popular Electronics

magazine article. In fact, the radar was designed during that era, so it is no surprise.

Our IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) secondary radar had a whopping 1 kilobyte

of magnetic core memory in its processor circuitry. It consisted of 1024 tiny toroids

mounted in a square matrix with four hair-width enamel coated wires running through

them as x and y magnetization current lines, sense, and inhibit functions. If my

memory serves me (pun intended) after three decades away from it, the TTL circuitry

(no microprocessor) stored range values to calculate speed and direction from sample

to sample. The other memory type was a mercury acoustic delay line contraption having

a piezoelectric transducer at one end to launch an electrical pulse along its length

and another transducer at the other end to convert back to an electrical pulse.

It was used to cancel out stationary targets (clutter) as part of the MTI (moving

target indication) circuitry in our precision approach radar (PAR).

The Electronic Mind - How it Remembers

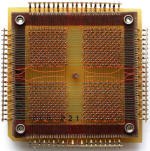

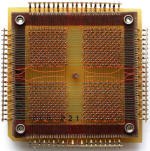

Close-up of magnetic core memory consisting of small ferrite

rings retaining information imparted through pulses from the wire network.

By H. H. Fantel, Associate Editor

Man's machines are doing the work of his muscles ... now, electronics explores

ways to take the load off his mind

When I was about five years old, I always carried a piece of string in my pocket.

I used to tie knots in it to remind myself of things I shouldn't forget. Without

knowing it at the time, I had, in effect, developed a "machine mind." To be sure,

it wasn't capable of very fine mental distinctions. But it could tell the difference

between yes and no. A knot meant "yes" (= there is something I ought to do). No

knot meant "no" (= relax and do nothing).

Today's digital computers use essentially the same system. Instead of a string,

there is a wire. Instead of a knot, there is a voltage pulse. Otherwise, it's the

same. The pulse means: go ahead and do something. No pulse means: rest.

In the language of computer engineers, each "pulse" or each "no-pulse" is called

a "bit," because each represents one specific bit of information. Together, and

arranged in logical sequence, billions of bits make up the complex patterns which

direct the computers toward the solution of a problem. Yet everything the machine

needs to know is broken down into simple yes-or-no propositions. "Pulse" or "no-pulse"

is all that any part of the machine ever needs to distinguish, all it ever needs

to remember. The computer's memory is therefore a device for storing electrical

pulses in predetermined patterns.

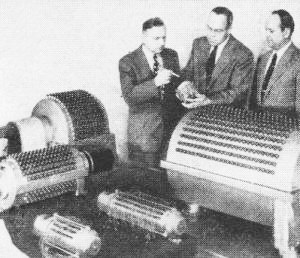

Over-all view of the basic components of a Univac computer. Behind

the control desk in foreground, the central computer mechanism occupies cabinet

at rear. The two round objects showing through open center door are mercury delay

lines, part of the machine's "internal memory." The array of tape recorders at right

serves as "external memory." Automatic typewriter in center spells out answers to

problems.

Human concepts expressed through words and numbers must be broken

down into simple yes-or-no "bits," somewhat like playing "20 Questions," except

that here the elementary items of information run into billions. This machine converts

numerical data from keyboard into monosyllabic computer code recorded on tape. The

information is then retained in the computer's "external memory."

Punched cards are also used to give instructions to the computer.

The pattern of holes is then converted into a sequence of electric pulses.

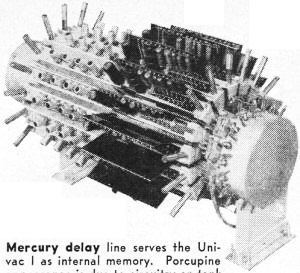

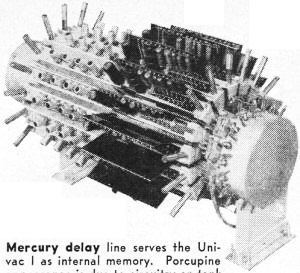

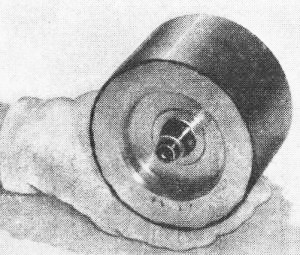

Mercury delay line serves the Univac I as internal memory. Porcupine

appearance is due to circuitry on tank surface, amplifying and re-shaping pulses

for endless repetition in this "talk-to-yourself" mumble-tub.

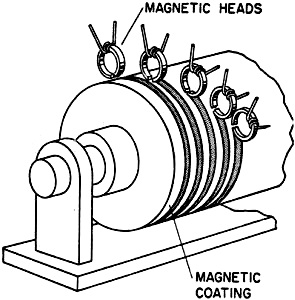

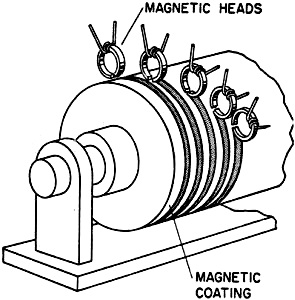

Magnetic drum principle is illustrated in simplified drawing

above. Each magnetic head reads or writes pulses received from the computer onto

its own track on the magnetically coated rotating drum.

Family of drums, ranging from giant roller to small twirler held

by the engineer, make a veritable "memory lane" for Remington Rand.

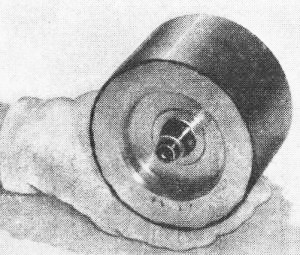

Small drum rotor whirls within the Univac at 16,500 rpm in an

atmosphere of helium, which reduces friction and draws off excess heat.

Magnetic core matrix is a net of tiny ferrite rings, each storing

one "bit" of information.

External and Internal Memory. Most electronic computers have

two basic types of memory - external and internal. As the names imply, the external

memory is a sort of auxiliary, tacked onto the central computer mechanism. The internal

memory is located right within the works of the computer.

The external memory acts as a go-between for the machine and its human masters.

It remembers the instructions given to the computer' by human mathematicians. By

setting up the external memory, scientists can "program" the computer to do a given

job. This memory also acts as a sort of "time transformer" to match the slow speed

of human beings to the high speed of the machine. Scientists might take days to

punch a set of instructions into the external memory. Later, the memory can reel

out this row of instructions fast enough to keep up with a computer when it zooms

through the whole problem.

Physically, the external memory takes the form of punched cards, magnetic tape,

or punched paper tape.

Punched cards and paper tape have long been in use with conventional office equipment

as data storage media - punched-card tabulating equipment, for example, has become

commonplace in American business, and the paper-tape-driven automatic typewriter

has relieved many a typist of repetitive labor. The data storage principle in each

of these cases is extremely simple: information is recorded on the card or tape

in the form of punched holes. A hole means an electric pulse; no hole, no pulse.

Because of the wide use of these storage devices, some computers have been equipped

with punched-card and punched-tape readers, and a number of machines have been developed

to convert these media automatically to magnetic tape.

In magnetic tape storage, the most commonly used form of external storage for

the electronic computer, characters are represented by combinations of tiny magnetized

and unmagnetized spots, each representing a "bit" of information. When data recorded

on the tape is fed into the computer, the magnetic tape reader translates the combination

of magnetized and non-magnetized spots to a series of electronic pulse/no pulse

combinations which, in computer language, have a definite meaning.

The great advantage of magnetic tape over other external memory devices is its

tremendous capacity. One reel of magnetic tape, eight inches in diameter and one-half

inch wide, can store approximately 2,880,000 characters, with up to 200 characters

recorded per linear inch. The tape will preserve data permanently and will not corrode.

It can be "erased" and used again for new data.

The machine uses its internal memory in the same way that human beings use scratch

pads in solving a math problem. It is a place to put down intermediate results and

the auxiliary numbers in the course of a calculation. Since such figures - in the

form of electronic pulses - must be quickly jotted down, stashed away, or shifted

from one place to another, some very tricky mechanisms were developed to do all

this juggling of "bits." Mainly, they are storage devices permitting information

bits to be quickly put in, quickly taken out, and accurately placed in a meaningful

over-all pattern.

Electrostatic Storage. These storage devices are cathode-ray

tubes resembling picture tubes in television sets. The screen of such a tube acts

like a checkerboard of small capacitors. Whenever the "writing beam" of the tube

hits one of the "squares" on this checkerboard, its capacitor effect stores up an

electric charge imparted to it by the beam. The guided beam places a pattern of

charged and uncharged areas on the checkerboard screen. Each area is a "bit," and

the arrangement of the bits on the board spells out a numerical meaning. This pattern

of electrostatic charges can be "read" by another beam scanning the area.

Information stored in such a way can be reached very quickly. It only takes between

five- and ten-millionths of a second to "read out" a digit of information and shift

it to wherever it is needed for the next logical operation of the computer. Because

the computer must spend much of its operating time searching its memory for data

and instructions, the speed of access to specific information largely determines

the over-all speed of the system.

The storage capacity of a single tube is limited usually to about 1000 bits.

Tubes can, of course; be used in combination to form large-capacity storage units.

One disadvantage of electrostatic storage is that the data are lost from the

tube's surface unless they are constantly regenerated by the writing beam. In other

words, the machine has to keep talking to itself to remember what it is saying.

Although this is done entirely by automatic circuitry, the stored data are lost

in the event of a power failure.

A certain unreliability stems from the fact that beam guidance is highly critical.

A small temporary voltage change on the deflection plates can direct the beam to

the wrong checkerboard area on the face of the tube, resulting in false information.

Frequent adjustment by engineering personnel is essential for operating reliability.

Electro-Acoustic Delay Line. One of the first memory systems

to gain wide commercial acceptance for electronic computers was the electro-acoustic

delay line. In simplest terms, a delay line memory stores electronic data by constantly

recirculating the information pulse pattern in the form of sound through a delay

element, usually a tank of mercury. At the precise moment when the information must

be inserted into the calculation, it is picked up by a "listening" device at the

far end of the tank and transferred to where it is needed. The memory tank can then

stop mumbling to itself.

The process may be likened to the short-range human device of repeating a phone

number to oneself from the time it is located in the phone book until it has been

dialed.

A mercury delay line memory channel consists simply of a mercury tank capped

at each end by a transducing crystal, and a closed recirculation circuit. As pulses

are delivered to the memory from the computer's control circuits, the crystal at

one end acts as a sort of loudspeaker and sends a series of pulse/no-pulse tones

through the mercury. These pulses thus travel through the mercury at the speed of

sound, much lower than the speed of electronic pulses through wire. This provides

the delay needed to hold information for controlled lengths of time.

As the pulses reach the end of the mercury column, they strike the second transducing

crystal - which acts as a microphone - and produce small electrical voltages that

can be amplified and fed back to the input. In this way, the bits continually go

in circles until they are replaced by other data from the control circuits. Then

the whole cycle starts anew.

Each tank has automatic counting devices, which count the number of times a message

is repeated. This provides accurate timing within a few thousandths of a second

for picking up the message when it is needed.

Magnetic Drum Storage. The magnetic drum is an aluminum cylinder

or "drum" coated with a magnetic material and equipped with a row of read-write

heads. As the drum spins at high speed, each head monitors a narrow "track" around

the circumference.

When data are to be stored, the pulse combinations are flashed to the heads and

are recorded in the form of magnetized and unmagnetized areas on the drum's surface.

The operation is very much like recording data on a broad, endless loop of tape

with many channels.

An important advantage of magnetic drums is their capacity; such drums are made

to hold as many as 2,552,000 bits, or about 350,000 characters. Other favorable

features are their .low cost and the fact that they retain stored data indefinitely.

Magnetic Core Memory. In recent years, pure physical research

has opened up new horizons through the discovery of a new basic material: the ferrites.

Their impact on electronics is a whole story in itself. Here we are concerned only

with their possibilities as memory devices.

Magnetic polarity can be established in ferrites by a current of sufficient strength.

Once established, the magnetic field resists change until an equally strong current

is passed in the other direction. Thus, for example, the magnetic field of a ferrite

with positive polarity can be reversed by applying a sufficiently strong negative

current.

Wikipedia Magnetic Core Memory photo

In computers, this physical fact forms the basis of a memory system. The ferrites

are shaped into doughnut-like rings, called toroidal cores, which are wired together

in checkerboard "matrices." A pair of wires, one horizontal and one vertical, intersect

at each core. To store an electronic "bit," it is only necessary to apply a polarizing

voltage to the pair of wires meeting at a certain core. The magnetic field of that

particular core will then shift and hold its new polarity, i.e., it will hold one

"bit" of pulse-type information. None of the other cores will be affected, since

the current in any one wire is not strong enough to reverse the cores' polarity.

Only at the intersection point of the two pulsed wires, i.e., at the desired core

location, do the two currents summate and thus achieve sufficient strength to evoke

magnetic response.

Magnetic core memory is the current favorite among computer engineers. The reasons

are easy to see. To "read out" the information stored in the core memory requires

no more time than it takes to send a "sensing" pulse along the diagonal lines to

pick up the pattern of magnetic shifts. Six characters can be transferred into or

out of the memory in about 20-millionths of a second. At this rate of figuring,

the answers come up fast.

Here, with the most advanced of memory devices, we are actually closest to my

erstwhile piece of string with the knots tied in it. We may quite literally think

of the pulsing wires as strings and of the magnetized cores as the knots. The magnetizing

pulses "tie" the knots, and the sensing pulses "feel along" the string to locate

the knots.

Of course, my string didn't know the meaning of the knots. Only I did. Neither

does the machine mind know the meaning of its memories. Only the creative mind of

a human being is able to translate pulses, "bits," characters, or even words and

numbers into the kind of living sense from which men build their world.

Posted January 31, 2023

(updated from original

post on 2/26/2016)

|