|

December 1965 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

A news story with a title about

a boat and reverse current is more likely to be referring to water flow in a river or

stream than about electrical current in a conductor. Having

grown up in a neighborhood

next to a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay, I spent quite a bit of time around boats,

both large and small. Salt water is particularly destructive to metal hulls due to

cathodic

corrosion, exacerbated by the salt water's conductivity. While working as an

electrician in the 1970s, I installed electrical supplies for a few dockside cathodic

protection systems that probably functioned like the one described in this 1965 issue

of Popular Electronics magazine. The principle is fairly simple whereby anodes

are placed in the water around the hull and a counter-current is induced to cancel the

natural current flow. Evidently the systems needed to be fine tuned so as to not harm

the hull's paint.

Reverse Current Keeps Ferry Afloat

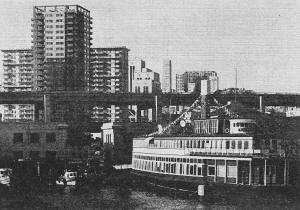

Converted ferry was stripped of machinery and engines, and connected

to city water, gas, electricity, etc. Problem was to prevent the hull from rusting away

without yearly dry-docking.

By William P. Brothers

When the San Francisco firm of J. Walter Landor ran out of space, it simply bought

one of the last of the Bay ferryboats. The company tied the boat up to a dock and converted

the topside into offices. Keeping the steel hull of the 40-year-old ferry from scuttling

the studios and staff was a problem.

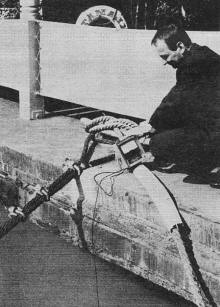

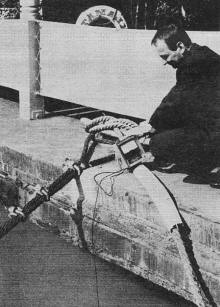

Electrical potential of steel hull is measured every month. Brass

studs brazed to hull give solid electrical contact, accurate reading. Amount of d.c.

current required depends on exposed hull area.

A permanently moored ferryboat is corroded by the electrolytic action of sea water.

One ampere of d.c. will wear away 20 pounds of steel each year. To overcome this action,

designer Alexis Tellis dropped four carbon anodes overside and fed them d.c.-reversed

to the corrosive action of the hull. A solid-state rectifier supplies 0.85-0.95 volt

to the rods. More voltage damages the paint; less voltage corrodes the hull.

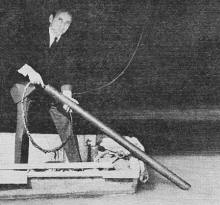

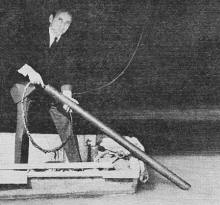

Designer Alexis Tellis examines one of four carbon anodes dropped

around steel hull. Anodes, charged with d.c. equal to that ferry would ordinarily lose

by electrolytic action, counteract current flow.

Posted May 22, 2018

|