|

September 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

People are entering

the field of electronics all the time and many want to learn not only circuit theory

and troubleshooting, but design as well. With all the pre-packaged integrated circuits

available that perform just about every function imaginable, there are still times

when you either want or need to set about designing your own circuit. Interfaces

between two circuits, or to displays and sensors are examples of the kinds of applications

that might need a custom design. That applies not only for RF type circuits that

require impedance matching, but also to low frequency analog and digital circuits.

This article by Mr. Jim Huffman, which appeared in a 1972 issue of Popular

Electronics, provides an introduction on how to methodically determine all

necessary requirements and then actually design your circuit - in this case an audio

amplifier. A technician I worked with in the early-to-mid 1980s who was an inspector

at Westinghouse Oceanic Division, in Annapolis, Maryland, designed a battery-powered,

pocket-sized amplifier for driving a set of headphones from his electric guitar.

It was his first "real" circuit design and he doted over it like it was his newborn

child. He came up with a great name for it: the "Jam Anywhere."

Simple Solid-State Circuits for the Experimenter

Basic Approach Enables Anyone to "Roll His Own" Amplifier

By Jim Huffman

You don't have to be a mathematical genius to design a simple solid-state amplifier.

All you have to do is follow some basic rules, cut-and-try a little, test the circuit,

and there it is! The mathematics involved in complete, top-level circuit design

require the knowledge of a graduate engineer; but, unless the circuit is critical,

there are some shortcuts that can be used by the serious electronics experimenter.

These shortcuts yield "ballpark" figures that work well with components having 5%

or 10% tolerances.

To explain what we mean by shortcuts and simplicity, we will use as an example

the design of a microphone preamplifier. In this design, math is at the high school

level, and Ohm's Law is the most complicated formula involved. All the designer

has to do is "plug in" the numbers necessary for his particular application.

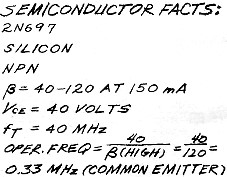

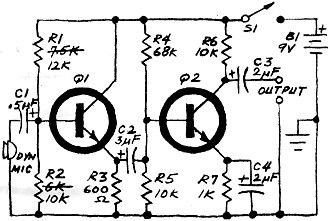

Fig. 1 - Write down basic circuit facts.

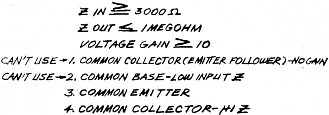

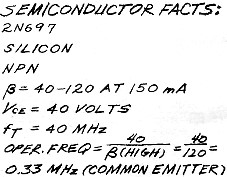

Fig. 2 - Consider transistor characteristics.

Fig. 3 - These are circuit parameters.

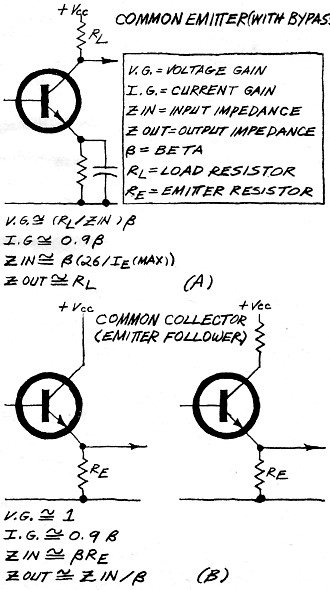

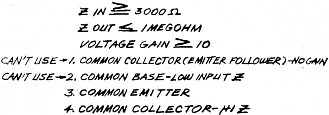

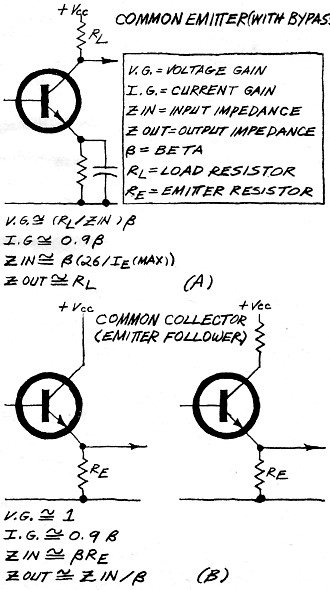

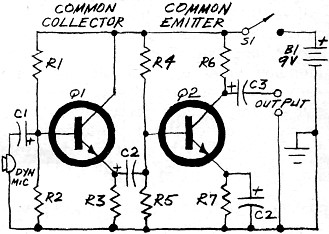

Fig. 4 - Two circuit configurations.

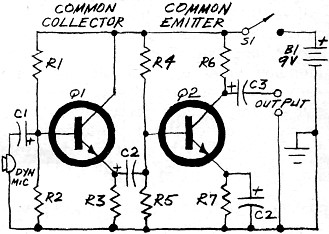

Fig. 5 - Draw basic circuit diagram.

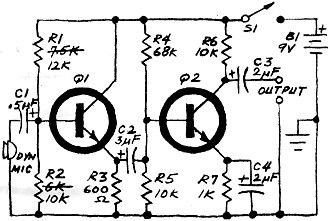

Fig. 6 - Determine the resistor values.

Fig. 7 - Convert to equivalent ac design.

Fig. 8 - This is the final circuit layout.

Fig. 9 - Testing input/output impedances.

Preamplifier Design

Suppose you want a microphone preamplifier that will match a low-impedance dynamic

mike to a modulator or power amplifier with an input impedance of one megohm. (In

other words, you want to make the dynamic mike "100k" like a crystal mike.) Note,

however, that the same procedure described here could be used for matching an input

device of any impedance to any circuit impedance simply by changing the necessary

figures and using the appropriate transistor.

The design is accomplished in eight easy steps:

- Write down all the pertinent facts about the circuit (see Fig. 1). It was determined

(by tests) that the output of a crystal mike hits a maximum of 0.5 volt (roughly

that of a crystal phonograph pick-up). The dynamic mike was connected to a VTVM,

and a no-load output voltage of 0.1 volt was measured when speaking loudly, so a

normal level of 0.05 volt was used. Thus, the voltage gain required of the amplifier

is about 10 (0.5/0.05). Since these are very rough approximations, a final voltage

gain of at least 20 was decided upon.

- Write down all available facts about the transistor. Since we have a 2N697 in

our junk box, we decide to try it (see Fig. 2). The 2N697 is silicon, so it is stable

with temperature. It is an npn and has a beta between 40 and 120 when the current

is 150 mA. Usually, we use the lowest beta figure, but since the 150 mA specified

for the 2N697 is considerably more than we need, we use a beta of 50. Since we are

using a nine-volt supply and the breakdown voltage, VCE, is 40, the device should

be safe. The gam-bandwidth product, fT, for the 2N697 is 40 MHz. Dividing

this value by the highest beta (120) gives a maximum frequency of 330 kHz, when

the device is used in the common-emitter configuration. This is well above the 3-kHz

maximum frequency required.

- Decide on a configuration, using the facts in Fig. 1. The parameters selected

are shown in Fig. 3. The input impedance may be hard to achieve with a common-base

amplifier; and since the voltage gain is more than unity, the common-collector approach

can't be used. The common emitter (Fig. 4A) looks good except that the input impedance

is higher than that normally associated with a common-emitter circuit. So we have

to add another stage (emitter follower) to raise the input impedance (Fig. 4B).

- Now we can draw a preliminary design, such as that shown in Fig. 5. The battery

supply is included, capacitors are marked for polarity, and components are numbered

for reference.

Note that single-battery bias is used. This bias method provides

better results as far as temperature stability and other factors are concerned.

Also, contrary to some beliefs, this is the easiest system to design.

- Calculate the data as shown in Fig. 6, using the data supplied in Fig. 4A for

the common emitter stage and Fig. 4B for the emitter follower. The most critical

parameter for the emitter follower is the output impedance. The latter is approximately

equal to the input impedance divided by beta, or 3000/50. So the output impedance

(or the emitter resistance) should be 60 ohms or more. This is easy to achieve since

the input impedance of the next stage is probably greater than 60 ohms. The actual

emitter resistor is R3, and to avoid as little loss as possible, we choose it to

be ten times the 60 ohms decided on for the emitter resistance. Thus, R3 = 600 ohms

or more. The "or more" tells us which way to go if we have to use other than a 600-ohm

resistor.

For stability, R2 should be about 10 times R3 or 6000 ohms.

The value of R1 depends on the value of bias current chosen. Since the stage

is a voltage amplifier, and since a 9-volt supply is used, there should be about

4 volts across R3 (including a 1-volt drop across the transistor). Thus, the voltage

at the base of the emitter follower should be four volts when there is no input

signal. To achieve this drop across R2, R1 has to be 7500 ohms. For the

common emitter stage, R7 is a non-critical value in most cases and can be "picked

out of the air." If the wrong value is chosen, we will find out later in the design.

A good value to choose for R7 is 1000 ohms. In this stage, as before, R5

is 10 times R7 or 10,000 ohms. The value for R6, which must be chosen before

R4 can be determined, will be approximately equal to the output impedance of the

amplifier. The modulator or power amplifier input is a voltage amplifier because

of the high impedance. Since the output of the preamp is required to be a voltage

generator, the output impedance can be much less than the input impedance of the

modulator or power amplifier. The stage need not transfer maximum power, only maximum

volts, so the impedances need not match. Essentially, the entire output voltage

from the common emitter stage will he felt at the input of the amplifier if the

output impedance is less than about 1/10 of the input impedance of the amplifier.

In fact, 1/100 would be a better figure, so R6 is chosen to be 10,000 ohms. Normally,

at this time, R6 would be considered in regard to the desired voltage gain. A quick

check shows that the 10,000-ohm value provides a gain of over 20. To make

sure that the output of the amplifier is class A (and since Q2 is a current amplifier,)

the bias through R6 is chosen to be half of its maximum value. The maximum current

through R6 will be about 0.73 mA (1-volt drop in the transistor) or about 0.36 mA

at the class A bias point. Resistor R4 is selected to provide the 0.36-mA

bias current. There should be about 0.36 volt across R1 with bias current flowing.

Since this is a small voltage, we must take into account the 0.8-volt drop at the

base-emitter junction of the transistor. Thus the voltage at the base of the transistor

must be 0.8 + 0.36 or 1.16. Resistor R4 is chosen to provide 1.16 volts across R5.

This turns out to be about 68,000 ohms.

- To calculate the ac values, redraw the circuit showing all bypassed resistors

as shorts to ac and the input impedance of the following stage as resistors (Fig.

7). Note that R1 and R2 in parallel form Rin which is in parallel with

Zin of the emitter follower to form the amplifier input impedance Since

the input impedance of the emitter follower is dependent on the input impedance

of the common emitter, we must determine the latter from Fig. 4A. Since Ic

= 0.36 mA and beta is 50, the input impedance is 3600 ohms. The latter is in parallel

with R4 and RS, the bias resistors. The parallel value of R4 and R5 is approximately

8800 ohms, which, in parallel with 3600, comes to about 2560 ohms.

The 2560

ohms is paralleled by the emitter follower's own R3 so the emitter sees about 500

ohms. The emitter follower input impedance becomes 500 times the beta or 25,000

ohms. The input impedance of the entire amplifier is RIN (3600)

in parallel with 25,000 or 3000 ohms, which is what is desired. If the values were

found to yield an overall input impedance which was not 3000 ohms, the components

would have to be adjusted appropriately. The voltage gain of the amplifier

depends on the gain of the common emitter stage, which, from Fig. 4A, is about 140.

Thus the amplifier meets the gain requirement of at least 20. Capacitor

values are chosen so that the response at 100 Hz is -3 dB. So, we lump the impedances

associated with a particular capacitor and solve for an equivalent Xc.

Since the input impedance is 3000 ohms, Xc1 = 3k and C1 is

0.5 μF (Xc = 1/2πfC). Keep in mind that, if you cannot hit this

value, a larger capacitance will only lower the response and probably won't be undesirable.

Bypass capacitor C4 is associated with a 1000-ohm resistor and its value

will he close to 2 μF. Capacitor C3 and the 10,000-ohm output impedance combine

for a value of 0.2 μF; and the reactance of C2 must be 500 ohms so its value

is about 3 μF. Insert all of the above figures into the circuit as shown

in Fig. 8.

- Breadboard the circuit. When substituting resistor values, keep the same ratio

between the values and increase or decrease until you come close to something you

have. For instance, assume you do not have a 7500- or 6000-ohm resistor for R1 or

R2. You know the values can go up, so find the ratio of R1/R2 - which is 1.25. An

increase in both values will merely raise the input impedance, which is not objectionable.

Thus, as shown in Fig. 8, R1 and R2 were changed to 12k and 10k, respectively, since

they were readily available.

If you want to change the value of R3, you

will have to go higher, since lowering its value would lower the 3000-ohm input

impedance. Keep in mind that, in some applications, the impedance may not be allowed

to be different from that calculated. Now we can build the circuit, apply

power and check the voltage levels at the emitters of both transistors. This tells

us whether the bias values are correct. It also tells us whether or not the circuit

will operate. Then we connect it to the other devices (mike and power amplifier)

to see if the whole thing works.

- You may not wish to perform this last step, but if you have an audio generator,

use the hookups shown in Fig. 9 to measure the important parameters of the circuit.

Figure 9A is used to measure input impedance. Adjust R1 until the voltage at the

input is half its maximum value. (The value of R1 should be greater than the estimated

input impedance of the amplifier. Then remove R1 and measure its rotor-to-end resistance.

This value will be approximately the same as the input impedance of the

amplifier. The output impedance is measured in the same way by adjusting

R2 in Fig. 9B. The voltage gain is found by using the circuit in Fig. 9C and dividing

the output by the input. Frequency response is found by adjusting the frequency

until two points are obtained at which the output is 0.707 times the maximum. These

are the upper and lower 3-dB power-loss points.

Now the design is complete. The checks should show any values that need adjusting.

Parts can now be purchased, printed circuit boards can be etched, etc., etc.

Posted November 4, 2019

|