October 1960 Popular Electronics

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

If you are looking for

a very thorough treatise on transformers, from AC line frequency up through audio

and RF frequencies, but without a lot of formulas to distract you, then this article

by Ken Gilmore is it. He begins with the fundamentals of a current setting up a

magnetic field, talks about mutual coupling and induction, step-up- and step-down

transformers, autotransformers, iron and laminated core transformers, multi-tap

voltage and impedance matching transformers, and even touches on the mage-size transformers

in electrical distribution system substations. Transformers fundamentally work the

same way today as they did when first invented in the 1830s. Equations for simulations

have been refined to the nth degree, but for the vast majority of mankind this article

will suffice to provide a better-than-a-layman's knowledge of the principles.

The Transformer

By Ken Gilmore

A fundamental coupling device, the transformer is one of electronics' most capable

magicians - here's what's behind its electrical sleight-of-hand and how it performs

its multitude of valuable tricks.

What the Transformer Does

The electrical power that makes your light bulbs glow, runs your refrigerator,

and operates your hi-fi set comes into your home at a potential of about 115 volts.

Yet if you were to climb the utility pole outside and measure the voltage there,

it could turn out to be as high as 6000 volts. If you kept on climbing poles at

other places around town, you might find voltages as high as 120,000 volts!

Even in your home, some appliances - air conditioners, clothes dryers, electric

ranges, and other heavy-duty equipment - may operate at 230 volts instead of the

usual 115 volts. And if you probe into your television set, you'll find an even

wider voltage range. For although your TV draws its power from the wall plug - and

power there is at 115 volts - your set has the ability to change this voltage into

a number of different values, so that each tube and circuit can operate under the

exact conditions it likes best. Consequently, in some places, you will find values

as low as one or two volts; in others, values as high as 15 or 20 thousand volts.

Electric power, one of our most useful servants, becomes tremendously more useful

when we can change it at will to dozens, or even hundreds, of different voltages.

Fortunately, we can make these changes easily and economically with a device known

as the transformer.

Transformers are all around us. One - the gadget about the size of a large garbage

can hanging near the top of utility poles - changes the 6000-volt transmission-line

power into the 115 and 230 volts you need. Another - this one about as big as a

flashlight - takes 6 or 12 volts from your car's battery, and changes it into the

10,000 or more volts needed to fire your spark plugs. Still another - a square can

a little bigger than your fist - channels high-fidelity electrical signals into

the speakers of your hi-fi set.

We'll talk more about these special applications - and others like them - a little

later. Right now, let's get down to the business of seeing just how a transformer

goes about performing this valuable electrical sleight-of-hand-changing one voltage

into another.

How the Transformer Works

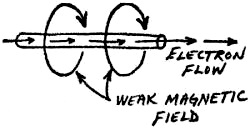

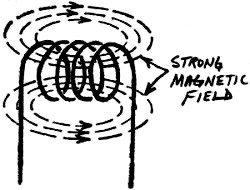

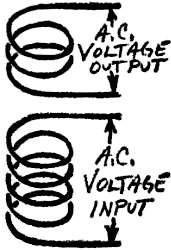

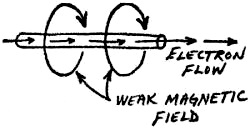

When an electric current flows in a wire,

a weak magnetic field is set up around it. If we twist the wire into a coil, the

weak field around each turn of the wire is reinforced by the fields around the other

turns; the result is a much stronger field. When an electric current flows in a wire,

a weak magnetic field is set up around it. If we twist the wire into a coil, the

weak field around each turn of the wire is reinforced by the fields around the other

turns; the result is a much stronger field.

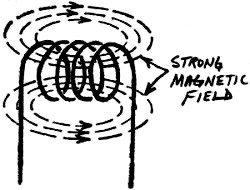

If an a.c, current flows in the coil, the magnetic field builds as the current

flows in one direction; dies down, or decays, as the current returns to zero; then

builds in the opposite polarity as the current flows in the other direction. You

can think of the building and decaying magnetic field as a pulsing, invisible force,

expanding and contracting as the current reverses its direction of flow. As the

field builds and decays, the magnetic flux lines (the circular lines in the diagram)

cut back and forth through the coil.

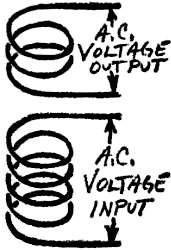

Now suppose we put another coil of wire

next to and in line with the first, although not actually touching it. As the magnetic

field expands and contracts, the flux lines will cut back and forth through the

second coil as well as through the first one, and a voltage will be induced in the

second coil. This is called "mutual induction," and is the basis of all transformer

action. Because of this property, a simple transformer can be made - and many are

- simply by placing two coils of wire close together and applying an alternating

current to one of them. Now suppose we put another coil of wire

next to and in line with the first, although not actually touching it. As the magnetic

field expands and contracts, the flux lines will cut back and forth through the

second coil as well as through the first one, and a voltage will be induced in the

second coil. This is called "mutual induction," and is the basis of all transformer

action. Because of this property, a simple transformer can be made - and many are

- simply by placing two coils of wire close together and applying an alternating

current to one of them.

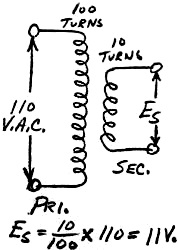

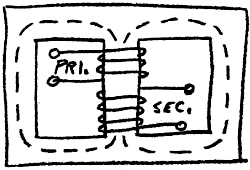

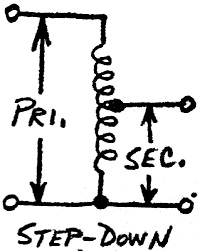

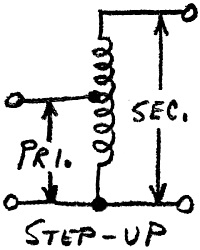

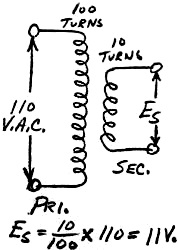

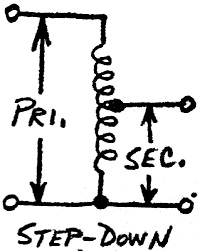

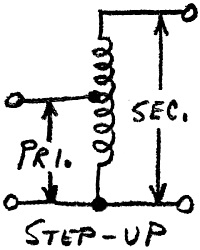

The main value of a transformer lies in the fact that the ratio of the voltages

in the two coils can be controlled by the number of turns of wire in each. To put

it another way, if the secondary (the coil into which voltage is induced) has ten

times as many turns of wire as the primary (the coil across which the original voltage

is applied), then the secondary voltage will be ten times the primary voltage. In

such a case we have a step-up transformer.

On the other hand, if the secondary has only one-tenth as many turns as the primary,

the secondary voltage will be one-tenth the primary voltage, and we have a step-down

transformer.

Efficiency

In the above calculations, we have assumed

that all magnetic lines of flux, as they expand and contract, cut all turns of the

transformer. The magnetic coupling in such a case would be 100%. Of course, in practical

transformers a few lines of force manage to stray outside the useful area. But by

careful design, engineers are able to produce transformers with efficiencies of

80%, 90%, and even more. In fact, for the purposes of most calculations, transformer

efficiency can be considered to be virtually 100%. In the above calculations, we have assumed

that all magnetic lines of flux, as they expand and contract, cut all turns of the

transformer. The magnetic coupling in such a case would be 100%. Of course, in practical

transformers a few lines of force manage to stray outside the useful area. But by

careful design, engineers are able to produce transformers with efficiencies of

80%, 90%, and even more. In fact, for the purposes of most calculations, transformer

efficiency can be considered to be virtually 100%.

Voltage vs. Current

Even though we can get a higher voltage from a transformer than we put into it,

the transformer is not capable of creating power. What we gain in voltage, we lose

in current. On the other hand, if we step down the voltage, we get more current.

If the current flowing in the primary of the step-up transformer in the diagram

above is 5 amperes and the voltage 110 volts, the power consumed in the primary

is 550 watts. Since the output voltage is 1100 volts, or ten times as much, we would

have available only one-tenth the current, or 0.5 ampere. Thus, even though we can

juggle voltages and currents at will, the output power is 550 watts - the same as

the primary input. (Actually, the output power would be slightly less than 550 watts,

due to the small losses in efficiency mentioned earlier.)

Iron Cores

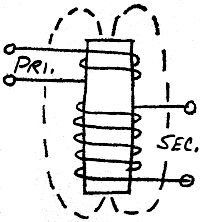

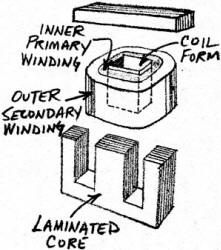

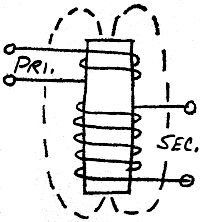

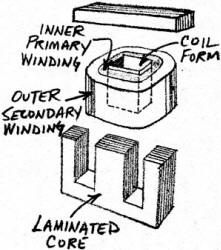

So far, we have described a transformer as two

coils of wire, placed close together along a common axis. Although some transformers

are actually built this way, most use other types of construction. Instead of being

placed side by side, the two coils are usually arranged with one coil inside the

other; this gives much closer and more efficient magnetic coupling. So far, we have described a transformer as two

coils of wire, placed close together along a common axis. Although some transformers

are actually built this way, most use other types of construction. Instead of being

placed side by side, the two coils are usually arranged with one coil inside the

other; this gives much closer and more efficient magnetic coupling.

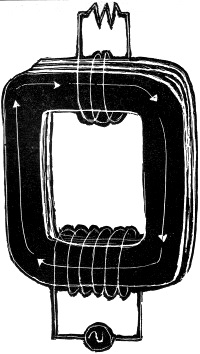

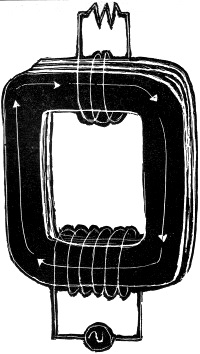

For use at low frequencies, designers wind the two coils around a common iron

core. Since iron is a much more efficient conductor than air, the magnetic field

built up is much stronger. That is, almost all the magnetic lines of force developed

by the primary winding are gathered up by the

iron core and shaped so that almost all

cut through the secondary winding. Therefore the efficiency of the transformer is

greatly increased. iron core and shaped so that almost all

cut through the secondary winding. Therefore the efficiency of the transformer is

greatly increased.

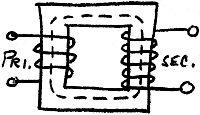

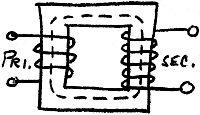

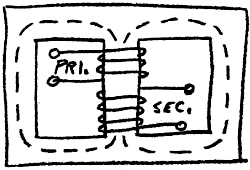

The diagrams at left show the three principal types of iron-core transformers.

First is the open-core transformer which, while possible, is never used because

of its relative inefficiency - a large part of the magnetic field would still have

to be in air, rather than in iron. The closed-core transformer is considerably more

efficient; and the shell core transformer is most efficient of all. The shell-core

type has another advantage: since the flux path is almost entirely contained in

the iron core, it is less subject to disturbances by external magnetic fields than

other types, and it doesn't disturb other nearby circuits as much.

Transformer Losses

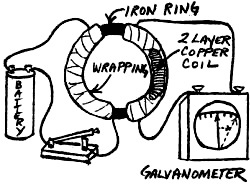

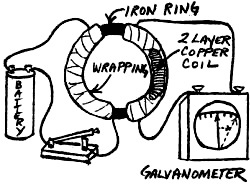

The first transformer ever made was simply

an iron ring with two 2-layer coils of wire wrapped around it. Its inventor was

Michael Faraday, the great English electrical pioneer. He discovered electromagnetic

or mutual induction - the principle upon which the transformer works - in 1831.

When he connected his primitive iron-ring transformer as shown, the galvanometer

needle jumped as the switch was closed. The first transformer ever made was simply

an iron ring with two 2-layer coils of wire wrapped around it. Its inventor was

Michael Faraday, the great English electrical pioneer. He discovered electromagnetic

or mutual induction - the principle upon which the transformer works - in 1831.

When he connected his primitive iron-ring transformer as shown, the galvanometer

needle jumped as the switch was closed.

Although Faraday's device was a true transformer,

its losses were high. Today's modern, refined transformers have assumed a wide variety

of sizes, shapes, and characteristics as engineers have attempted to minimize the

losses that are a part of every transformer's operation. Although Faraday's device was a true transformer,

its losses were high. Today's modern, refined transformers have assumed a wide variety

of sizes, shapes, and characteristics as engineers have attempted to minimize the

losses that are a part of every transformer's operation.

Transformer losses come from many different

sources. First, not every magnetic flux line cuts the secondary - some simply travel

out into space, consuming energy from the primary, but doing no useful work. This

loss is called flux leakage. Designers minimize it by careful physical arrangement

of the coils and core. Sometimes the primary is wound on the core first, then the

secondary applied on top. At other times the secondary is split into two layers

with the primary in between. Transformer losses come from many different

sources. First, not every magnetic flux line cuts the secondary - some simply travel

out into space, consuming energy from the primary, but doing no useful work. This

loss is called flux leakage. Designers minimize it by careful physical arrangement

of the coils and core. Sometimes the primary is wound on the core first, then the

secondary applied on top. At other times the secondary is split into two layers

with the primary in between.

Copper Losses

The so-called copper losses are caused by the electrical resistance of the transformer

windings. Although copper is a good conductor, it has a measurable resistance, as

does any conductor. When current flows through this resistance, heating takes place

and power is wasted. As a result, almost any transformer will feel warm to the touch

when operating normally, and some are actually hot.

Core Losses

Since the iron core itself, as well as the

coils, is cut by the expanding and contracting magnetic field, a current is induced

here, too. As this eddy current flows in the core, it steals energy from the primary

circuit and dissipates it as useless heat. The eddy current flows at right angles

to the magnetic flux. It can be reduced by substituting several thin layers of iron

for the solid core. These thin layers - laminations - are separated by layers of

glue which electrically insulate the laminations from each other. In practice, a

small eddy current is set up separately in each lamination, but the total loss is

much less than for a solid-core transformer. Since the iron core itself, as well as the

coils, is cut by the expanding and contracting magnetic field, a current is induced

here, too. As this eddy current flows in the core, it steals energy from the primary

circuit and dissipates it as useless heat. The eddy current flows at right angles

to the magnetic flux. It can be reduced by substituting several thin layers of iron

for the solid core. These thin layers - laminations - are separated by layers of

glue which electrically insulate the laminations from each other. In practice, a

small eddy current is set up separately in each lamination, but the total loss is

much less than for a solid-core transformer.

Still another core loss is caused by the alternating current itself. Since this

current reverses its direction 120 times a second, the iron core - in effect, an

electromagnet - must continually reverse its polarity. And since the minute magnetic

elements in the core tend to resist this change, power must be expended to realign

them. This is called hysteresis loss. Engineers reduce it by building transformer

cores of steels which change magnetic polarity with comparative ease, so that less

power is consumed in making the switch.

Miscellaneous Losses

Since the turns of wire in a transformer

are close together, there is some distributed capacitance between the turns, between

different layers of windings and between separate windings. This capacitance, though

small, is cumulative. Like a small capacitor connected across the transformer, it

shorts out some of the voltage developed across the windings. At low frequencies

(the usual 60 cps of house current, for example) this loss is unimportant, but at

higher frequencies engineers must go to great lengths to minimize it. Since the turns of wire in a transformer

are close together, there is some distributed capacitance between the turns, between

different layers of windings and between separate windings. This capacitance, though

small, is cumulative. Like a small capacitor connected across the transformer, it

shorts out some of the voltage developed across the windings. At low frequencies

(the usual 60 cps of house current, for example) this loss is unimportant, but at

higher frequencies engineers must go to great lengths to minimize it.

Another small loss is caused by the imperfection of transformer insulation. A

small leakage current will flow through almost any insulator, and thus absorb some

of the transformer's power. This is known as dielectric loss.

Then, too, particularly at high frequencies, a transformer can begin to act as

a small but efficient radio transmitter, and actually radiate power like a broadcast

antenna. This is called transmission loss.

Most of these losses, under normal conditions, are minor, but at times they become

serious. For example, eddy current losses are small at power-line frequencies, but

at the high end of the audio spectrum - say around 20,000 cps - they become significant.

This means that a poorly designed transformer in the output stage of a hi-fi amplifier

will operate much less efficiently at 20,000 cps than at 1000 cps; the result is

poor frequency response.

To minimize eddy currents designers specify thinner laminations. Where laminations

20 to 25 thousandths of an inch thick are used in power transformers designed to

work at 60 cps, audio transformers rarely have laminations thicker than 10 or 15

thousandths of an inch. For really good hi-fi reproduction, lamination thicknesses

may range from ten thousandths of an inch all the way down to only one thousandth

of an inch.

Higher and Higher Frequencies

As frequencies go still higher, even one

thousandth of an inch is too much, and eddy current losses become excessive. Consequently,

r.f. transformers frequently have cores made of minute grains of iron suspended

in an insulating material and compressed under high pressure into a solid mass.

Since the grains are insulated from each other, they break up the eddy current path

and help reduce eddy current losses. As frequencies go still higher, even one

thousandth of an inch is too much, and eddy current losses become excessive. Consequently,

r.f. transformers frequently have cores made of minute grains of iron suspended

in an insulating material and compressed under high pressure into a solid mass.

Since the grains are insulated from each other, they break up the eddy current path

and help reduce eddy current losses.

As might be expected, the size of the iron granules becomes important as the

frequency increases, since at high frequencies eddy currents are even set up within

the individual granules. Granules several thousandths of an inch thick are satisfactory

below 100,000 cps, but as the frequency goes higher the particles cannot be larger

than several millionths of an inch thick.

A new type of magnetic core made of iron ferrite has recently allowed designers

to build iron-core transformers to operate at frequencies higher than ever before.

These ferrites - varieties of iron oxide, or rust - are valuable because they have

magnetic properties, and yet are insulators and do not conduct current. Because

of the unusual construction of these transformers, no eddy currents form.

If you have bought an ultra-portable radio recently, you are benefiting from

ferrite-improved transformers. Miniature radios of even a few years ago had loop

antennas at least 8 to 10 inches long and almost as high to collect enough signal

to operate. Now ferrite-core antennas, far more efficient because of their magnetic

core but not susceptible to eddy current ills, can be built as small as a short

pencil. As a result, portable radios can now be produced smaller than they have

ever been produced before.

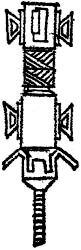

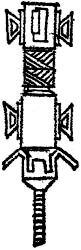

In many applications, particularly for very

high frequencies, air-core transformers are used. The coils are wound on a non-magnetic

form such as Bakelite or polystyrene. The coils may be concentric, or end to end.

Frequently one is movable, so that the degree of coupling between them is adjustable. In many applications, particularly for very

high frequencies, air-core transformers are used. The coils are wound on a non-magnetic

form such as Bakelite or polystyrene. The coils may be concentric, or end to end.

Frequently one is movable, so that the degree of coupling between them is adjustable.

One of the biggest problems in high-frequency transformer design, particularly

where multiple layers of winding are involved, is stray capacitance. If a regular

winding were used, with adjacent layers lying parallel to each other, this capacitance

could become intolerable. Consequently, layers are frequently spiraled back and

forth as in the transformer shown in the drawing at right. This makes adjacent layers

cross each other almost at right angles instead of being parallel, and stray capacitance

is materially lowered as a result.

How the Transformer is Used

The transformer invented in the 1830's wasn't put to work outside the laboratory

until 1885 when William Stanley, an engineer who worked for George Westinghouse,

designed and tested a transformer power-distribution system. He used a 500-volt

generator and fed the power directly into a 4000-foot transmission line. A transformer

to step down the voltage to 100 volts was used at the other end of the line.

Westinghouse wasted no time in putting Stanley's superior transmission system

into operation. That same year he built the first plant especially designed for

transformer power distribution in Buffalo, N. Y. It went into use on November 30,

1886. His generator produced a 1000-volt, 133-cps output which was fed directly

into the transmission line, and stepped down at the customer's home.

In spite of its obvious superiority, however, high-voltage transmission with

transformers did not gain immediate acceptance. Thomas Edison, for one, was violently

opposed to a.c. power, and he used his tremendous prestige to gain support for his

own d.c. system. Consequently, it was not until many years later - after the turn

of the century - that high-voltage a.c. power distribution became common. Even today

there are a few places - some areas of New York City, for example - still receiving

Edison's legacy of d.c. power.

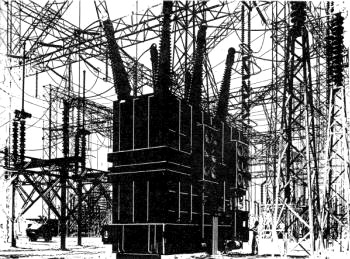

But giant power transformers and their complex distribution stations now dot

the landscape all over the country. The one shown on the next page, one of the largest

ever built, can handle enough electric power for a city of 500,000 inhabitants.

Power Distribution

Why use transformers for power distribution?

The efficiency of transmission is tremendously increased by stepping up the voltage

to as much as several hundred thousand volts. Also, a given size of wire can carry

far more power at high voltage than low, saving money in transmission costs. Let's

see why. Why use transformers for power distribution?

The efficiency of transmission is tremendously increased by stepping up the voltage

to as much as several hundred thousand volts. Also, a given size of wire can carry

far more power at high voltage than low, saving money in transmission costs. Let's

see why.

As an example, let's take a transmission line of No.1 wire 10 miles long - that's

a conductor about the size of your little finger. The resistance of one such wire

10 miles long is about 7 ohms. (Actually, the resistance of each wire in the transmission

pair is 7 ohms but for the sake of illustration let's consider just one.) Now let's

say that we transmit a current of 120 amperes at 120,000 volts (a common transmission-line

voltage) over the 10 miles. The total power fed into the line at the generating

station is 14,400,000 volt-amperes.

With 120 amperes flowing in the 7-ohm line, the voltage drop over the ten miles

will be 840 volts. Thus, the output voltage will be 119,160 volts; 120 amperes at

119,160 volts gives a 14,299,200 volt-ampere output. Along the line we have lost

100,800 volt-amperes, dissipated by the resistance of the transmission line. This

seems like a lot of power, but if we figure it in terms of percentage, the loss

amounts to a negligible 0.7% of the total fed into the line.

Now let's see what happens if the supply voltage is reduced to only 12,000 volts.

The power input is now 1,440,000 volt-amperes. We will assume that the transmission

line is still carrying 120 amps - its maximum load under any conditions. Since the

current and resistance are the same, the voltage drop over the 10 miles will also

be the same - 840 volts. The loss in the transmission line will still be 100,800

volt-amperes, but now this represents a whopping 7% of the total fed into the transmission

line.

Obviously, the high-voltage transmission is far more efficient. As also demonstrated

in this example, the transmission line can carry far more power under high-voltage

conditions. For these reasons, all transmission lines operate at higher voltages

than those delivered to your electric meter by the power companies.

At Niagara Falls, N. Y., for example, hydroelectric generators produce power

at 6000 volts. It is immediately stepped up by transformers to 120,000 volts and

fed to long-distance transmission lines. At various points it is stepped back down

to 6000 volts for distribution over local areas, then stepped down once again to

230 and 115 volts for home use.

Power Transformers

Although a power-distribution transformer

is more spectacular, you're much more likely to be familiar with the ordinary power

transformer used in radios, amplifiers, and TV sets. Such devices have a primary

winding and usually several secondary windings to meet the various voltage and current

requirements of a receiver or amplifier; a drawing of a typical power transformer

is shown at right, above. The primary is usually designed for 115 volts; the high-voltage

secondary may produce anywhere from 250 to as high as 600 or 700 volts (higher for

some purposes). The other secondaries, usually rated at 5.0 and 6.3 volts, are for

tube filaments. Although a power-distribution transformer

is more spectacular, you're much more likely to be familiar with the ordinary power

transformer used in radios, amplifiers, and TV sets. Such devices have a primary

winding and usually several secondary windings to meet the various voltage and current

requirements of a receiver or amplifier; a drawing of a typical power transformer

is shown at right, above. The primary is usually designed for 115 volts; the high-voltage

secondary may produce anywhere from 250 to as high as 600 or 700 volts (higher for

some purposes). The other secondaries, usually rated at 5.0 and 6.3 volts, are for

tube filaments.

Power transformers are available with a wide variety of windings and current

capabilities. They may have four, five, six, or even more windings, each rated at

a different voltage for some specific purpose. The high-voltage winding of a light-duty

power transformer may be capable of producing perhaps only 30 or 40 ma., while a

heavy-duty unit may turn out 300, 400, or even 500 ma. Transformers for high-power

transmitters produce voltages and currents far in excess of these values, but for

such applications separate transformers are generally used for high-voltage and

filament supplies.

Audio Transformers

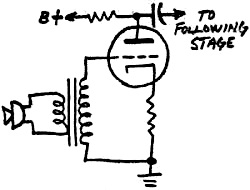

So far, all the transformers we have talked

about in detail are designed for use in power circuits which operate at 60 cps.

But transformers can operate on a wide variety of frequencies - every audio amplifier

uses at least one transformer of this sort, and many include several such transformers. So far, all the transformers we have talked

about in detail are designed for use in power circuits which operate at 60 cps.

But transformers can operate on a wide variety of frequencies - every audio amplifier

uses at least one transformer of this sort, and many include several such transformers.

Although the same basic principles of step-up and step-down are used in audio

transformers, this is usually of secondary importance to the transformer's ability

to serve as an impedance-matching device. Take, for example, an input transformer.

Here it may be necessary to match a phonograph pickup, a microphone, or other input

source of as little as 200 or 300 ohms (even less, in some cases) to a grid circuit

of as much as several hundred thousand ohms. If the pickup or microphone were connected

directly to the grid, a serious mismatch would occur, which would not only reduce

the efficiency of the circuit but upset frequency response as well. The input transformer

matches the components so that each operates properly.

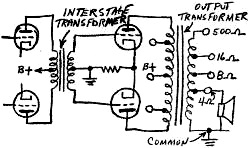

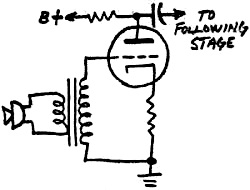

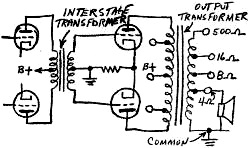

The interstage transformer is another variety

of the audio transformer and performs much the same kind of job: matching the output

tube-several thousand ohms-to a grid circuit of a much higher impedance. The interstage transformer is another variety

of the audio transformer and performs much the same kind of job: matching the output

tube-several thousand ohms-to a grid circuit of a much higher impedance.

A third variety is the output transformer, whose main task is again impedance-matching.

The plate circuit of the output tubes may have an impedance of many thousands of

ohms, while most loudspeakers are 4, 8, or 16 ohms. To accommodate various tube-speaker

combinations, most output transformers have a series of "taps" on the secondary

winding, and perhaps on the primary as well, so that windings of the proper impedance

can be selected. Only the part of the transformer windings actually used (in 'the

diagram, the portion between the first and second terminals) affects the circuit's

impedance values. One form of output transformer - known as a "universal" type -

is so designed that it is capable of matching virtually any possible tube and speaker

combination.

Better and Better Design

Great progress has been made recently in

audio-transformer design. Just a few years ago it was difficult to get a transformer

with any appreciable output above, say, 10,000 to 15,000 cps. Today, transformers

with flat outputs up to 20,000 cps are common, while units flat to 50,000 or even

100,000 cps are available. Great progress has been made recently in

audio-transformer design. Just a few years ago it was difficult to get a transformer

with any appreciable output above, say, 10,000 to 15,000 cps. Today, transformers

with flat outputs up to 20,000 cps are common, while units flat to 50,000 or even

100,000 cps are available.

Tremendous problems had to be overcome to produce today's outstanding transformers.

In addition to the losses mentioned earlier, a transformer has inductive reactance

which varies according to frequency (remember that a transformer is also a coil).

At frequencies of 100 and 1000 cps, the inductive reactance of the primary will

be 10 and 100 times, respectively, its value at 10 cps. The inductive reactance

appears to the output tube's plate as a load resistance, and thus various amounts

of amplification take place at various frequencies. As a result, the gain of the

amplifier is about two-and-a-half times higher at 200 cps than at 10 cps. At 3000

cps it would be three times higher. At still higher frequencies, distributed capacitance

becomes an important factor, and gains fall off rapidly.

Engineers go to great lengths to compensate for these effects; by means of special

core materials, unique coil designs, special wrapping patterns, interlaced layers,

and other techniques, they have produced a variety of audio transformers with unbelievably

even response over an extremely wide range of frequencies.

R.F. Circuits R.F. Circuits

As mentioned earlier, transformers are also widely used in r.f. circuits. Even

the simplest five-tube a.c.-d.c. radio will usually have as many as four transformers,

in addition to its audio output transformer. A typical radio, for example, might

have an antenna coil (actually a small transformer which couples the antenna's output

into the grid of the first amplifying tube), an oscillator coil (a transformer which

supplies feedback for the oscillator), and two i.f. transformers which couple the

various stages.

These transformers are likely to be air, powdered-iron, or ferrite-core transformers,

since a regular iron core would cause intolerable eddy-current losses. The windings

will also probably be of a special spiral design calculated to minimize capacitance

effect,

Special Purpose Transformers

Although the transformers we have been discussing make up the bulk of those used,

there are many other types, all of which perform their useful, specialized jobs.

The autotransformer, for example, uses only

one winding instead of two, but accomplishes an effect similar to that of a regular

transformer. If the whole coil is used as the primary and only a portion as the

secondary, then it is a step-down unit. Hooked in reverse, it is a step-up device.

This transformer, of course, cannot be used in circuits which must be electrically

isolated from each other. But it serves very well in your automobile where it draws

current from the 6- or 12-volt battery or generator and puts out the 10,000 or more

volts needed to fire your spark plugs. The autotransformer, for example, uses only

one winding instead of two, but accomplishes an effect similar to that of a regular

transformer. If the whole coil is used as the primary and only a portion as the

secondary, then it is a step-down unit. Hooked in reverse, it is a step-up device.

This transformer, of course, cannot be used in circuits which must be electrically

isolated from each other. But it serves very well in your automobile where it draws

current from the 6- or 12-volt battery or generator and puts out the 10,000 or more

volts needed to fire your spark plugs.

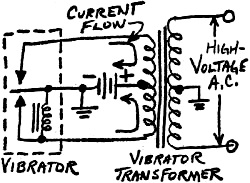

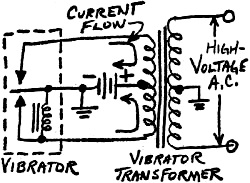

While we're on the subject of your automobile,

let's take a look at the car radio which uses another kind of specialized device,

the vibrator transformer. This device effectively "transforms" d.c. As the vibrator

element moves back and forth touching each contact in turn, current flows through

each half of the primary alternately, with each pulse going in a different direction.

With the proper turns ratio, the output from the original 6- or 12- volt d.c. source

can be as much as several hundred volts a.c. While we're on the subject of your automobile,

let's take a look at the car radio which uses another kind of specialized device,

the vibrator transformer. This device effectively "transforms" d.c. As the vibrator

element moves back and forth touching each contact in turn, current flows through

each half of the primary alternately, with each pulse going in a different direction.

With the proper turns ratio, the output from the original 6- or 12- volt d.c. source

can be as much as several hundred volts a.c.

Photoflash transformers, used to operate photographer's electronic flash or "strobe"

units, are also vibrator-operated. They can take the vibrator-interrupted output

from a 1 1/2-volt battery and turn it into several thousand volts a.c.

Pulse transformers are used primarily in

radar. They range from tiny units (several of which can fit in a thimble) that put

out a few millionths of a watt to huge, multi-ton giants that transmit powerful

million-watt pulses. These transformers are designed to step up odd-shaped waveforms

without changing the waveshape. Pulse transformers are used primarily in

radar. They range from tiny units (several of which can fit in a thimble) that put

out a few millionths of a watt to huge, multi-ton giants that transmit powerful

million-watt pulses. These transformers are designed to step up odd-shaped waveforms

without changing the waveshape.

One of the newest types - transistor transformers - are similar to those used

in regular r.f. and a.f. circuits except that their impedances and voltage ratings

are calculated to match the operating requirements of transistors. Some of these

units, by the way, can fit in a cube three-eighths of an inch square, and they weigh

only a fraction of an ounce.

Thus, through the ingenuity of the design engineer, the transformer - though

always operating on the same simple principle discovered by Faraday - can be adapted

to perform hundreds of useful and important services.

Posted March 1, 2022

(updated from original post on 5/14/2014

|

So far, we have described a transformer as two

coils of wire, placed close together along a common axis. Although some transformers

are actually built this way, most use other types of construction. Instead of being

placed side by side, the two coils are usually arranged with one coil inside the

other; this gives much closer and more efficient magnetic coupling.

So far, we have described a transformer as two

coils of wire, placed close together along a common axis. Although some transformers

are actually built this way, most use other types of construction. Instead of being

placed side by side, the two coils are usually arranged with one coil inside the

other; this gives much closer and more efficient magnetic coupling.

In many applications, particularly for very

high frequencies, air-core transformers are used. The coils are wound on a non-magnetic

form such as Bakelite or polystyrene. The coils may be concentric, or end to end.

Frequently one is movable, so that the degree of coupling between them is adjustable.

In many applications, particularly for very

high frequencies, air-core transformers are used. The coils are wound on a non-magnetic

form such as Bakelite or polystyrene. The coils may be concentric, or end to end.

Frequently one is movable, so that the degree of coupling between them is adjustable.

The autotransformer, for example, uses only

one winding instead of two, but accomplishes an effect similar to that of a regular

transformer. If the whole coil is used as the primary and only a portion as the

secondary, then it is a step-down unit. Hooked in reverse, it is a step-up device.

This transformer, of course, cannot be used in circuits which must be electrically

isolated from each other. But it serves very well in your automobile where it draws

current from the 6- or 12-volt battery or generator and puts out the 10,000 or more

volts needed to fire your spark plugs.

The autotransformer, for example, uses only

one winding instead of two, but accomplishes an effect similar to that of a regular

transformer. If the whole coil is used as the primary and only a portion as the

secondary, then it is a step-down unit. Hooked in reverse, it is a step-up device.

This transformer, of course, cannot be used in circuits which must be electrically

isolated from each other. But it serves very well in your automobile where it draws

current from the 6- or 12-volt battery or generator and puts out the 10,000 or more

volts needed to fire your spark plugs.  While we're on the subject of your automobile,

let's take a look at the car radio which uses another kind of specialized device,

the vibrator transformer. This device effectively "transforms" d.c. As the vibrator

element moves back and forth touching each contact in turn, current flows through

each half of the primary alternately, with each pulse going in a different direction.

With the proper turns ratio, the output from the original 6- or 12- volt d.c. source

can be as much as several hundred volts a.c.

While we're on the subject of your automobile,

let's take a look at the car radio which uses another kind of specialized device,

the vibrator transformer. This device effectively "transforms" d.c. As the vibrator

element moves back and forth touching each contact in turn, current flows through

each half of the primary alternately, with each pulse going in a different direction.

With the proper turns ratio, the output from the original 6- or 12- volt d.c. source

can be as much as several hundred volts a.c.