October 1960 Popular Electronics

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

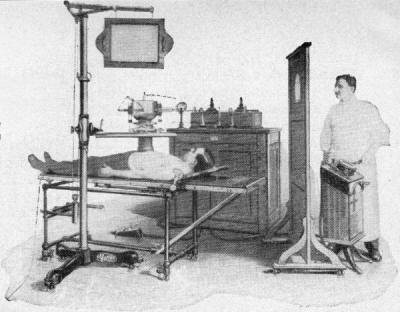

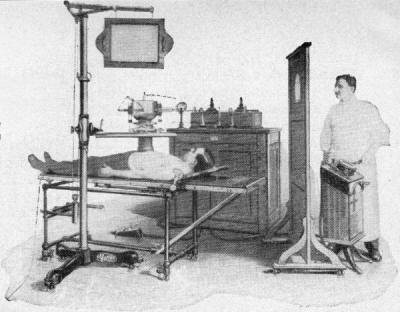

Looking at the first

picture reminds me of a scene in Star Trek VI

where Mr. Chekov takes a fall while exploring a "nuclear wessel" and is left

unconscious. By the time Capt. Kirk and Dr. McCoy get to him, the doctors

have prepared Chekov for 20th-century-style brain surgery. McCoy is abhorred over

the "midievalism" technique that actually requires cutting open the skull to treat

the injury. Instead, the good doctor passes his humming little device over Mr. Chekov

and heals him instantly. Someday, if mankind or an asteroid doesn't wipe out civilization,

we probably will reach the point of Dr. McCoy's magic brain healing gizmo. I

will reassert the "barbaric" description here regarding how scary-looking early medical x-ray

machines were as shown in the October 1960 issue of Popular Electronics

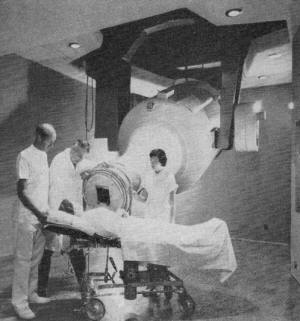

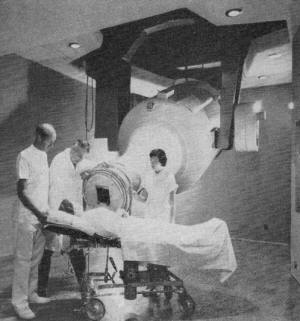

magazine. Admittedly, being stuffed inside a modern MRI machine and having the loud

electromagnetic coils cycling is no relaxing trip to the countryside, but the

early machinery was downright frightening. See also "Electronics Against

Cancer" for more info. Looking at the first

picture reminds me of a scene in Star Trek VI

where Mr. Chekov takes a fall while exploring a "nuclear wessel" and is left

unconscious. By the time Capt. Kirk and Dr. McCoy get to him, the doctors

have prepared Chekov for 20th-century-style brain surgery. McCoy is abhorred over

the "midievalism" technique that actually requires cutting open the skull to treat

the injury. Instead, the good doctor passes his humming little device over Mr. Chekov

and heals him instantly. Someday, if mankind or an asteroid doesn't wipe out civilization,

we probably will reach the point of Dr. McCoy's magic brain healing gizmo. I

will reassert the "barbaric" description here regarding how scary-looking early medical x-ray

machines were as shown in the October 1960 issue of Popular Electronics

magazine. Admittedly, being stuffed inside a modern MRI machine and having the loud

electromagnetic coils cycling is no relaxing trip to the countryside, but the

early machinery was downright frightening. See also "Electronics Against

Cancer" for more info.

After Class: X-Rays

By Fred E. Ebel, W9PXA By Fred E. Ebel, W9PXA

Discovered by chance only 65 years ago, X rays are one of our most valuable research

tools

Is it light?

No.

Is it electricity?

Not in any known form.

What is it?

I don't know.

With such scientific frankness did physics professor Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen

relate his discovery of a mysterious new ray to a newspaper reporter. Stumbled upon

by accident during a routine laboratory experiment on the night of November 8, 1895,

the new ray was dubbed an "X ray" by Roentgen. "X," then as now, was the mathematical

symbol for the unknown.

Much of the "X" has been taken out of X rays since the modest German physics

professor demonstrated this startling radiation and its power to penetrate tin,

paper, wood, and even the human body. When X-rays were first put into use, you ordinarily

had to visit a hospital to see them in action. Today, unlimited industrial applications

make X rays far more than just a diagnostic and therapeutic tool of medical science.

Chance - or Fate? Just

what did happen on the night of November 8, 1895? Call it fate, fortune, or chance,

but there were a number of conditions that conspired to make this night one to remember.

First, Roentgen had completely covered the Crookes tube he was using with a black

cardboard, making it light-tight. Secondly, his laboratory itself was plunged in

darkness. Finally, the piece de resistance - a sheet of paper painted with crystals

of barium platinocyanide - lay on a bench some distance from the tube. Chance - or Fate? Just

what did happen on the night of November 8, 1895? Call it fate, fortune, or chance,

but there were a number of conditions that conspired to make this night one to remember.

First, Roentgen had completely covered the Crookes tube he was using with a black

cardboard, making it light-tight. Secondly, his laboratory itself was plunged in

darkness. Finally, the piece de resistance - a sheet of paper painted with crystals

of barium platinocyanide - lay on a bench some distance from the tube.

The barium platinocyanide screen was the "chance" that nature gave Roentgen to

unlock one of her secrets. For when the crystals glowed with a shimmering yellow-green

fluorescence, Roentgen's keen scientific mind became curious. True, cathode rays

could make the crystals glow - but at this distance? He placed the crystal screen

at an even greater distance from the tube than the range cathode rays were known

to penetrate. Still the strange fluorescence!

Heart pounding, he grabbed a book and placed it between the Crookes tube and

the screen. The crystals continued to glow. Whatever it was, it was coming through

the book! Next, he tried metals - and found that the rays penetrated in varying

degrees, although lead and platinum stopped them completely.

Now came the most dramatic test of all.

Roentgen exposed his hand, and - his heart

must have almost stopped - saw the shadows of his bones. As Roentgen made photographs

of his findings, it was obvious that he had found something far more exciting than

cathode rays - X rays! Roentgen exposed his hand, and - his heart

must have almost stopped - saw the shadows of his bones. As Roentgen made photographs

of his findings, it was obvious that he had found something far more exciting than

cathode rays - X rays!

How X Rays Are Formed. How was Roentgen able to produce these

powerful rays with his crude apparatus - a modified Crookes tube, mercury interrupter,

and a Ruhrnkorff induction coil that furnished a bare 20,000 volts? The simple fact

is this: X rays are relatively easy to generate. You simply speed up electrons and

let them collide with a target. The electrons cause disturbances within the atoms

of the target, releasing X rays. Any material, even a gas or liquid, will release

X rays when bombarded by high-velocity electrons.

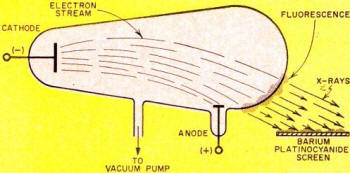

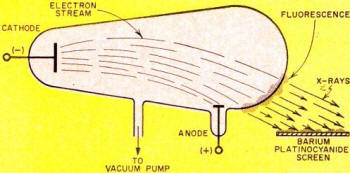

Obviously, then, glass can be a target, as is was in the Crookes tube Roentgen

used - see Fig. 1. Here a gas-type tube, consisting of an anode and cold cathode,

was connected to a high-tension induction coil. Heavy positive ions in the residual

gas were drawn to the negative cathode (unlike charges attract), striking with such

force that they knocked electrons from the cathode metal. It was this positive-ion

bombardment that created and maintained a source of electrons, the "work horses"

for X-ray generation.

The negatively charged electrons, in turn, were drawn toward the high-voltage

positive anode. The resultant stream of electrons, actually cathode rays, traveled

so fast - about 30,000 miles per second - that most of them could not "turn the

corner" to reach the anode. Instead, they smashed into the glass wall of the tube.

The glass, therefore, was the target, providing the barrier for the sudden stoppage

of electrons. The result: radiation of X rays, and, of course, the glow of fluorescence

of the glass that Roentgen observed.

Fig. 1 - Crookes tube used by Roentgen produced X rays when

electrons flowing from its cathode to its anode bombarded the glass tube.

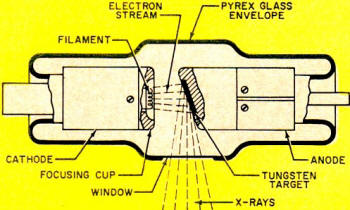

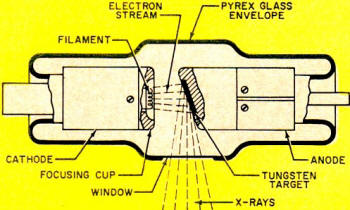

Fig. 2 - Basic X-ray unit includes X-ray tube and high-voltage

supply.

Fig. 3 - X-ray tube detail. The focusing cup concentrates

electron stream from cathode and directs it toward tungsten target material.

Nature of X Rays. X rays are electromagnetic rays similar to

visible light rays, with this important exception - their wavelength is very small,

about 1/10,000th that of light. These tiny wavelengths are measured in angstroms,

units so small that you can line up 254,000,000 of them between the one-inch marks

on a ruler. The X-ray region in the electromagnetic spectrum ranges from about 0.006

to 1000 angstrom units. Interestingly enough, it is this exceedingly short wavelength

of X rays that makes possible their penetration of matter, and which enables the

researcher to delve into the vast voids of molecular inner space.

Unlike the cathode ray generated in your TV picture tube, X rays are non-electrical.

Thus, they are unaffected by electrostatic and magnetic fields. This can be proved

by placing a magnet or charged plate near X rays; they "ill be neither attracted

nor repelled as in the case of cathode rays.

Traveling at e same speed as light and radio waves - 186,000 miles per second,

X rays can be reflected and refracted only at very small angles. (Roentgen failed

to focus X rays, despite many experiments with lenses of wood, glass, aluminum,

and other materials, for this reason.)

The darkening of photographic film by X rays has given them wide application

in medicine, research, and industry. A radiograph used by makers of cast-metal products

is actually a shadow picture of the subject. The dark regions of the film represent

the more penetrable parts - gas pockets in a weld, for example; the lighter regions

identify the more opaque areas.

How X Rays Work. A basic X-ray unit is comprised of filament,

high-voltage transformer and timing circuits - see Fig. 2. The heart of the

unit is the X-ray tube. Like Roentgen's original tube, the modern tube also has

a cathode and an anode, but with tremendous improvements. Now the tube is evacuated

to an extremely high vacuum. The cathode structure contains a coil of tungsten wire

- the filament - which "boils off" electrons when heated to incandescence. A metal

reflector or focusing cup on the cathode directs the electron beam toward the target-as

shown in Fig. 3.

Tungsten is ordinarily used for the target material, since it can withstand high

temperatures without melting. This is important because less than 1% of the energy

in the electrons is converted to X rays upon bombardment with the target; most of

the energy is converted to heat. To help dissipate the heat, the tungsten is imbedded

in a large mass of copper which conducts the heat into air or into oil, as in the

case of the oil-immersed tube.

It is desirable to have the focal spot - the area of the target that receives

the electron bombardment - as small as possible. The smaller the focal spot, the

better the detail of the radiograph. But a small focal spot means an intense blast

of electrons in a tiny area; even tungsten melts under such grueling treatment.

This problem can be solved by simply rotating the anode target. The target constantly

turns another "face" to the electron stream, area - see Fig. 4.

An induction motor provides the rotating power in an ingenious way. The stator

surrounds the outside of the evacuated glass bulb tube and provides the rotating

magnetic field that turns the rotor in the tube at approximately 3000 rpm. The rotor

in the "neck" of the tube is, of course, connected to the target. The entire moving

assembly is located inside the evacuated tube.

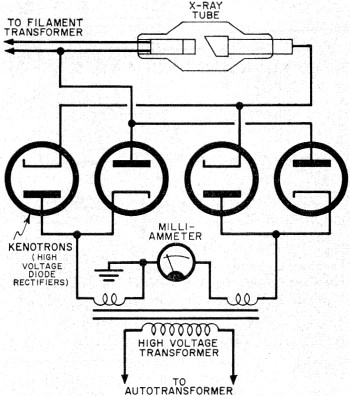

The high-voltage circuit consists of a step-up transformer and its controls;

an autotransformer supplies voltage to the primary winding of the high-voltage transformer.

Any change of the autotransformer voltage produces a corresponding change in the

high-voltage output which is applied to the X-ray tube. Changes in voltage are made

with a selector switch; increasing the tube voltage results in a decrease in wavelengths

of X rays, accompanied by an increase in penetrability.

Fig. 4 - Rotating anode in target constantly turns new face

to electron stream in order to distribute heat over a wide area.

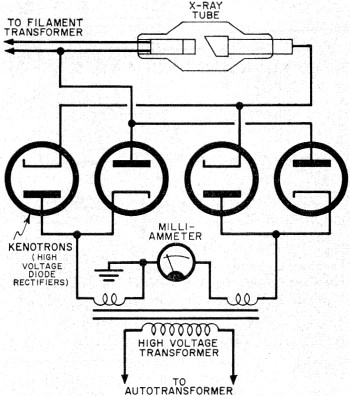

Fig. 5 - High-voltage rectifier circuit used in some X-ray

systems.

If "soft" X rays of low penetrability and longer wavelengths are desired, the

selector switch is set at about 20,000 volts. But if "hard" X rays of high penetrability

and shorter wavelengths are desired, the switch is set for several hundred thousand

volts.

Rectification of the high-tension alternating current to the tube can be very

simple - in fact, the circuit can be made self-rectifying. Current will flow through

the tube only on the half cycle when the anode is on its negative half cycle, since

the anode now repels the negative electrons. Some X-ray systems use a high-voltage

full-wave rectifier circuit, permitting conduction of current through the tube on

each half cycle of alternating current-see Fig. 5.

Present Day Uses. Quality control in manufacturing makes extensive

use of the non-destructive quality of X rays in the inspection of casting and weldments

for such defects as cracks and gas pockets. X-ray devices in beverage plants "look

into" opaque cans moving rapidly on a conveyor line and give the signal for automatic

rejection of under-filled cans.

Similar devices reveal foreign bodies in food stuffs; detect the hollow heart

of potatoes; separate pithy from juicy oranges; and reveal the improper assembly

of electronic tubes, switches, and small electrical assemblies. X rays also gauge

the thickness of electroplating, as well as that of hot steel strip racing along

at 4000 feet per minute in a rolling mill.

Dramatic applications abound in X-ray diffraction. Here, X rays are made to bounce

off mirror-like atomic planes of crystalline substances to reveal secrets of inner

structure. Nylon, magnetic TV tape. synthetic rubber, high-temperature alloys, high-test

gasolines, and penicillin are just a few of the products X-ray diffraction has helped

to develop or improve.

Art museums use X rays to examine the authenticity of old paintings. In other

applications, X rays distinguish real diamonds and pearls from their imitations.

Biologically Speaking. It is now well known that X rays as well

as gamma rays can mutate or change the genes (hereditary units) of our bodies. Excessive

X-radiation can also affect flesh, bone, and blood destructively. For these reasons,

it is of utmost importance that exposure to radiation be kept at a minimum.

What can be done in this respect? So far as background radiation is concerned,

even Adam and Eve had to contend with the small amount of gamma radiation from radioactive

material which occurs naturally in soil, rocks, and even plants. In fact, there

are radioelements in our bodies that give each of us a daily unavoidable radiation

dose of 0.0001 roentgen. (The roentgen is the unit of X- and gamma-ray dose.) In

addition, cosmic rays from interstellar space add to our daily dose of background

radiation.

In essence, X rays are simply a form of man-made radiation, but new techniques

and advancements greatly reduce the effects of their exposure to patients. Diagnostic

voltages now up to 150 kv. permit much shorter exposure times, as do faster films.

Significant, too, are collimators that confine the X-ray beam to the exact area

desired.

All in all, few would deny that the tremendous diagnostic and therapeutic benefits

of X rays far outweigh any possible deleterious effects. In fact, many a man, woman,

and child is alive today because of Roentgen's startling discovery. Since that eventful

night in 1895, these once strange and unknown rays have done much to alter the nature

of the world we live in.

Posted June 18, 2021

(updated from original post on 5/20/2014)

|

By Fred E. Ebel, W9PXA

By Fred E. Ebel, W9PXA