| June 1944 Popular Mechanics |

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

mechanics and electronics. See articles from

Popular Mechanics,

published continuously since 1902. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The mention of magnesium

(Mg) often - maybe usually - invokes thoughts of a material that spontaneously

bursts into flames when it comes into contact with water. It is true when a

non-oxidized Mg surface meets water, but a protective layer of oxide quickly

forms on surfaces exposed to air, rendering it inert. In fact, the machining

process continuously exposes raw magnesium, so special precautionary processes

are required. This story about the Basic Magnesium, Inc. (BMI) magnesium

processing plant just a few miles from the Boulder Dam (now called the Hoover

Dam) in Nevada (from which it consumed a third of its generating capacity)

appeared in a 1944 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine. At a third the

weight of steel (atomic #12), magnesium was a critical component of aircraft

structures and engines during World War II. Vast amounts of electric power was

required, as evidenced by this passage: "BMI borrowed some 20,000 tons of coin

silver from the Treasury, shaped it into metal planks to serve as electrical bus

bars, and installed it in the plant. The silver is worth $23,313,000 and will be

returned to the Treasury after the war. It is perfectly safe where it is in

spite of its value. No one would dare to touch it, considering the heavy current

that it carries."

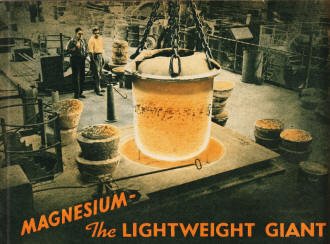

Magnesium - The Lightweight Giant

A safe bet is that none of your friends

can name the third largest city in Nevada. A safe bet is that none of your friends

can name the third largest city in Nevada.

There are some 10,000 people in this city, yet you won't find it on your map.

It is a modern community of air-conditioned homes with its own schools and churches,

and it's so new that its inhabitants got around to naming it only a few months ago.

Two years ago Henderson, Nevada, didn't exist. Now it is the "lightweight metal

capital of America." As much magnesium was refined there last year as was produced

in the United States during the 27 years preceding Pearl Harbor. The plant of Basic

Magnesium, Inc., is producing more magnesium than any other plant on earth.

Magnesium is the wonder metal that weighs one third less than aluminum and that

has the greatest strength-weight ratio of all commercial structural materials. After

the war you can expect to find it in your automobile, saving you money by the reduced

weight the engine has to pull. You can look for it in your kitchen where it will

save money again because of its great heat conductivity when used as cooking utensils.

You may find it in lightweight furniture, typewriters that weigh only a few pounds,

and paper-weight vacuum cleaners.

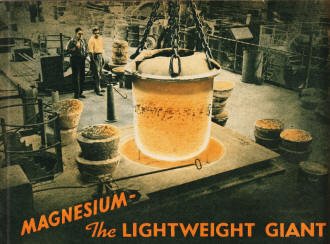

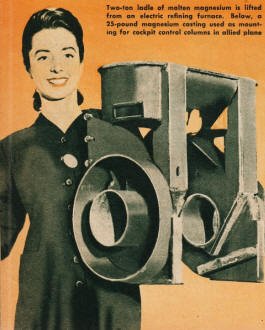

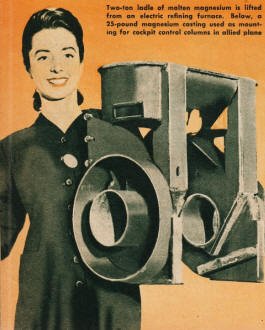

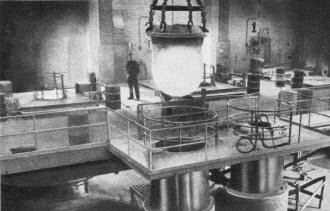

Two-ton ladle of molten magnesium is lifted from an electric

refining furnace. Below, a 25-pound magnesium casting used as mounting for cockpit

control columns in allied plane.

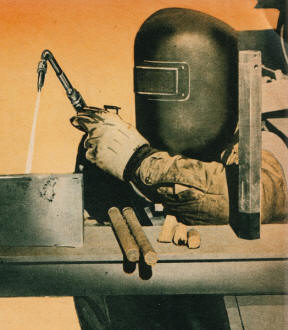

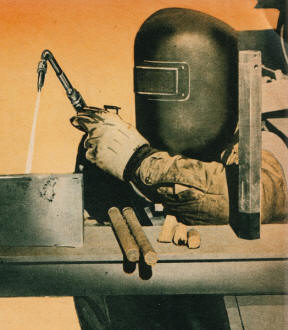

Welder cuts through solid magnesium to show that it resists combustion,

except under special circumstances.

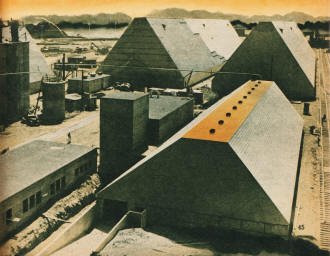

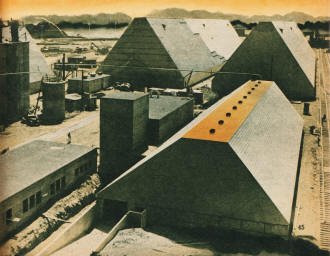

Storage tanks are at the Basic Magnesium, Inc., plant.

Trucks haul crude magnesite ore from mine to adjacent BMI plant,

largest of its type in the world.

Conduits and pipes under plant's rectifier building where alternating

is changed to direct current.

Finished bars of refined magnesium as they look when ready for

shipment. The Nevada plant produces more than 50,000 tons a year.

At present, of course, all the magnesium that America can produce is needed for

aircraft construction. Every piece of heavier metal that can be replaced by magnesium

in an airplane increases the plane's cargo capacity. These days such cargo often

consists of incendiary bombs and tracer bullets that are also made of magnesium.

Right here is a good place to dispel a popular misunderstanding about magnesium's

inflammability. Incendiary bombs made of it burn with terrible heat, but your future

magnesium pots and pans won't catch fire. Solid magnesium can be ignited only by

special sources of high heat.

Magnesium is one of the most common constituents of the earth and it also occurs

in sea water and brines, but America produced relatively little of it until the

war brought on a sudden, desperate demand. Of the plants that were erected in a

rush to produce it, the most unique in many respects is BMI, which is located 20

miles from Boulder Dam and about 300 miles from a huge magnesite deposit.

The BMI plant ranks among the greatest single enterprises ever built by man.

It cost $150,000,000. The plant, which is so big it could cover the entire business

section of Los Angeles, has its own bus and taxi service inside the gate for transporting

workers and officials on the job. It is using one third the generator capacity of

Boulder Dam, enough electricity to light Los Angeles. Two transmission lines with

a capacity of 230,000 volts each extend from the dam to the plant. Its water requirements

are on a similar scale and it draws its water from Lake Mead behind the dam from

the end of a special cantilever bridge that projects out from shore. The electrical

installation is second largest in the world and the air conditioning sys-tem, to

draw off gases and maintain equable temperatures, is the world's largest.

Millions of pounds of copper were used in the electric installation but even

this was not enough. Because of other war demands for copper, BMI borrowed some

20,000 tons of coin silver from the Treasury, shaped it into metal planks to serve

as electrical bus bars, and installed it in the plant. The silver is worth $23,313,000

and will be returned to the Treasury after the war. It is perfectly safe where it

is in spite of its value. No one would dare to touch it, considering the heavy current

that it carries.

Essentially the process used at BMI consists of changing magnesite, or magnesium

carbonate to an oxide, then to a chloride, then breaking down the magnesium chloride

into metallic magnesium and chlorine gas.

The magnesite is blasted out of a hillside in 10,000 ton amounts, is concentrated,

and shipped by rail or truck to the main plant. Here it is heated to drive off carbon

monoxide, converting it to an oxide, and is then mixed with calcined magnesite,

peat moss from Canada, coal from Utah, and special salts. After pellets of this

material are burned to produce porosity they are placed in huge electric furnaces

into which blasts of pure chlorine gas are also introduced, changing the magnesium

oxide to magnesium chloride. The chloride, in a molten state, is then transferred

to huge electrolytic cells where, under the influence of direct current, the molten

magnesium metal collects in pools on the surface of the electrolyte. The metal is

then cast into pigs and is taken to a refinery building where it is remelted together

with fluxes that carry off any impurities. The refined metal is then cast into ingots.

BMI was designed to produce some 50,000 tons of magnesium per year. Today, under

the management of Anaconda Copper Mining Company, it is producing more than 100

percent of its rated capacity. Magnesium is already cheaper than aluminum, copper,

and other metals on a cubic foot basis. With further reduced costs, magnesium will

be on a competitive per pound basis.

Magnesium is alloyed with other metals for most uses. Such an alloy may run 80

percent magnesium with various percentages of aluminum, zinc, manganese, or other

alloying materials. One magnesium-aluminum alloy, for instance, is three times as

strong as its weight in ordinary steel. Magnesium alloys are stiff metals of high

machinability. They may be cast, die-cast, forged, extruded, welded, rolled, and

fabricated in every known way.

Magnesium has been widely used in Europe in automobile bodies, truck bodies,

and in lightweight railroad rolling stock in addition to its uses in aviation. Right

now, it's called the "Victory metal." After the war it will be one of the new metals

of peace.

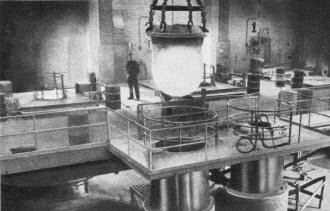

Lowering crucible of molten magnesium metal into cooling chamber.

At Basic Magnesium, Inc., magnesite is changed into an oxide and then to a chlorine,

which is broken down into metallic magnesium and chlorine gas.

Water storage tanks under construction.

Posted January 26, 2024

|