July 1944 QST

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

This is another installment of the Hams in

Combat series that QST magazine ran during WWII. I enjoy waxing vicariously nostalgic

of a time before I was born, at time when there was still honor, courage, selflessness,

and pride of country. During World War II, it was an ingrained part of most citizens,

whether or not they happened to be serving in the military. Our modern day troops

still have it, but sadly fewer and fewer people see their own country as any place

special in the world. Sure, as

General William Tecumseh Sherman famously said,

"War is hell," but then again so is witnessing the tearing apart of your country

from forces within - an "enemy at the gates,"

or a "fifth column," so to speak.

A Lady of Mercy

By S/Sgt. John F. Wojtkiewicz W3GJY-W4GQJ By S/Sgt. John F. Wojtkiewicz W3GJY-W4GQJ

A FEW DAYS after the bombing raid on Violet we were on our way back to Carnation.

There was constant air activity. Allied planes of all types moved in endless patterns

across the Mediterranean to Rose. Every now and then an Allied fighter would swoop

low over us and dip his wings in salute. Something about those fast, devastating

fighters commanded respect. But it couldn't compare to the feeling I had when we

passed a fleet of American warships traveling in a single, majestic line. They had

just come back from pasting a port in Rose and seemed to possess an air of quiet

satisfaction. I helped dip the Lady Luck's flag in salute to the fleet, experiencing

a feeling of complete reverence as I did so.

Ashore in Carnation the following afternoon I found there was strict curfew and

no one was supposed to be in the city unless on official business. Not wanting to

stay in the outskirts of the city I hailed a Navy truck hauling supplies and gave

the driver a long, sad tale about friends I had to see in Carnation. Being a sympathetic

soul he told me to climb in with the supplies and smuggled me through the military

police. The MPs must have figured I was on official business, for once I was inside

no one bothered me.

I reached a section of the city where row after

row of buildings lay in ruins. A small boy who spoke a little English appointed

himself my guide. As we walked along he pointed to this and that building, telling

me which had been bombed by the RAF and which by the Americans.

When we reached Cafe Roma I gave the boy some chewing gum and thanked him for

the tour. Seating myself at a corner table, I ordered a bottle of wine. A few minutes

later two of the mates from the Lady Luck entered the cafe and, needless to say,

they joined me in a series of toasts. I say "series of toasts" because that's the

seamen's way of excusing the system of multiple drinking they employ.

Before long the world suddenly seemed very wonderful. The people of Carnation

were wonderful. We were wonderful. One of the mates could speak the language of

the people fairly well and soon we were surrounded by a crowd of them, three deep.

Through the mate's interpretation we exchanged viewpoints on the war, the wines,

the customs, the cigarettes and the future.

It was now six o'clock and we had orders to be back at the ship by eight. We

bade the people good-by and started off in search of a ride. We were in luck; within

five minutes a jeep picked us up and deposited us right in front of the dock gates.

We presented our papers and started for the boat which was to take us to the Lady

Luck.

Suddenly the three of us halted in our tracks. There, dead ahead, was the Lady

Luck's tall stack moving out to sea. We stared dumbly. It couldn't be. We still

had an hour and a half of liberty time. I made a feeble joke about being left behind

in Carnation, but the response was even weaker. No matter how much of an adventurer

one is at heart, it is no fun to be stranded in a foreign port in wartime without

proper papers.

Then one of the mates went into action. Rushing up to the skipper of an LCI boat,

he told of our plight. Now, a mate carries quite a bit of authority, but an LCI

doesn't chase fleeing ships just to deliver a few stragglers. I waited for the skipper's

polite refusal. But, unaccountably it was a deal - the LCI would take us.

The LCI's engines roared and away we went after the Lady Luck, now a good six

miles ahead of us. It was exhilarating to feel the power of those engines under

the thin steel deck. The propellers churned up a mountainous peak of water as they

bore along under full throttle and I felt (with the help of a couple of bottles

of wine) like the hero in a movie thriller.

A half hour went by and the lights of the Lady Luck seemed no nearer. An hour

passed and still we seemed no closer. It didn't make sense. The Lady Luck can only

do sixteen and a half knots wide open and there would be no reason for her to be

going full blast. The LCI should do better than eighteen knots and we were wide

open. Still, the fact remained that it would take three or four hours to catch her

at the rate we were going. We tried blinking her down, but there was no answering

light. The LCI's skipper was very nice - but enough was enough. He had patrol duty

that night, so we had to turn back.

There was nothing to do but go on patrol duty with the LCI. Personally, I was

quite in the mood for it by then, for the wine was having its full effect. I took

one last look at the fleeing Lady Luck and then settled down to enjoy whatever might

come.

It was a very dark night with everything blacked out. Suddenly a huge, black

hull loomed up. With all guns trained on the LCI it challenged us. We all tensed

until the LCI established its identity, for one shot from the cruiser's lightest

gun would have blown us to very small bits.

In spite of anticipated action I slept peacefully the night through, awakening

the next morning to see Carnation bathed in warm, peaceful sunshine. Looking out

on the bay I saw, of all things, the Lady Luck. I couldn't believe my eyes. Why

would she be back in Carnation after racing out to sea like a scared rabbit the

night before? I woke up the mates from the Lady Luck and asked them if I was seeing

things. They assured me I was not. Thanking the skipper of the LCI, we made our

way back to our ship. Never has anything seemed so good as the moment I planted

my feet on the Lady Luck's deck.

It turned out that the captain had been told to anchor a safe distance outside

Carnation to escape the expected air raid. Naturally the ship. couldn't wait for

us, so it just went ahead according to orders. During the night a German Focke-Wolf

flew over the Lady Luck and circled as though picking the best place to drop its

bombs. While the raider was circling the Lady Luck it spotted a destroyer about

a mile away. After gaining altitude for a moment, it dove on. the destroyer, releasing

its bombs - all of which, however, fell wide.

The destroyer in the meantime had signaled a near-by airfield that the Lady Luck

was being attacked. In no time American night fighters were overhead and the German

raider was brought down in flames.

We took on casualties that afternoon. For the first time I learned that the constant

sound of rifles we had been hearing in the outskirts of the city was the firing

of snipers. After that, when-ever I heard the crack of a rifle I felt sure that

the sniper had me singled out for a pot shot.

Not far out of Carnation I went below to the administration office of the Lady

Luck. There, lying on the floor on stretchers, were badly wounded men, many of them

in agony. Yet every one of them returned smile for smile as I passed by, as much

as to say: "Don't worry about me; I'm okay." It made me wonder, seeing those men

as they were then, what right anyone has to complain about rationing, taxes, no

cars or little gasoline ....

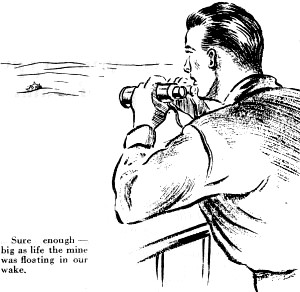

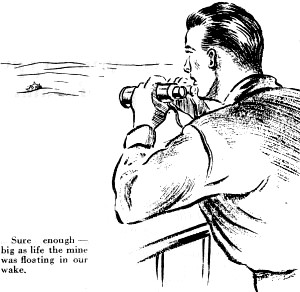

When I reported back to the bridge a few minutes later the captain looked worried.

I soon discovered why. We had, by deft maneuvering, just missed a floating mine.

Not one of the small or medium-sized kind, but a big one. It would have blown the

Lady Luck in half had we struck it. I looked astern through the field glasses and,

sure enough, big as life the mine was floating -in our wake. The horns standing

out on the surface of the mine (its contact points) looked more wicked and diabolic

than those of the devil himself at that moment. When I reported back to the bridge a few minutes later the captain looked worried.

I soon discovered why. We had, by deft maneuvering, just missed a floating mine.

Not one of the small or medium-sized kind, but a big one. It would have blown the

Lady Luck in half had we struck it. I looked astern through the field glasses and,

sure enough, big as life the mine was floating -in our wake. The horns standing

out on the surface of the mine (its contact points) looked more wicked and diabolic

than those of the devil himself at that moment.

There was nothing the Lady Luck could do about the mine. We had no guns to set

it off. Yet it was a crime to let it float around to blow another ship to bits.

At that moment a plane appeared overhead. When it turned out to be an Allied plane

we signaled a message reporting the mine and its location.

This time we took the casualties to Orange Blossom instead of Violet. The harbor

of Orange Blossom is strictly man-made. A long sea wall runs almost parallel with

the shore, and at a glance one can see why it is such an important Allied base.

The next morning I went ashore into the city of Orange Blossom. There I got the

full impact of the food shortage when I saw a group of poorly dressed natives standing

around begging, not for money but for any small particle of food we could give them.

When I arrived back at the ship there was great excitement aboard. A rumor was

circulating that we were going back to the States. It seemed too good to be true,

but when the captain came aboard he confirmed it. We were heading back to the States

that very day.

While we were taking on fuel in the afternoon all hell broke loose in the hills

behind Orange Blossom. Big guns started blasting and the din was terrific. We all

looked heavenward to see what enemy craft had been spotted, but no planes were in

sight. It turned out that the Army was trying out some big guns. I don't know the

value of those guns as weapons, but if they won't hit the enemy they surely will

scare him to death.

Late that night we were on our way to get our clearance papers. I could fairly

hear an official coming aboard and saying: "Sorry, but your orders have been changed."

But no - the Lady Luck was cleared within a matter of minutes, and soon we were

on our way out into the open sea.

For days after we left there was a stiff head-wind,

but the weather was clear and the sea steady. The night of August 25th brought hurricane

warnings from Nova Scotia. According to the reports a full gale was offshore, heading

toward Nova Scotia, and would probably hit the following night. The next day the

wind got stiffer, but it was nothing to worry about and most of us figured we would

probably escape the main blast. But that night all hell broke loose around the Lady

Luck.

The sea seemed to come to a boil. Odd pieces of equipment broke loose on deck,

and even good sailors were getting that telltale look symptomatic of seasickness.

I thought of the casualties below and the misery such a sea would bring them. But

soon I forgot everything except the Lady Luck herself. I wondered if she would break

in two as she spanked down on the sea after sticking her bow sickeningly upward

over the combers that drove in at us. The gale was terrific now and the sea was

being whipped into a white lather. The captain issued orders for all ship's personnel

except those on watch to stay below, and for everyone to stay away from windows.

Some thought the last was a foolish order since the glass in the Lady Luck was half

an inch thick -surely enough to withstand any sea.

By now the blow was at its worst. The doctors, nurses and enlisted men's crews

all were suffering violently from seasickness. They could barely hold their heads

up, yet there was so much that had to be done for the casualties.

Accidents began to multiply. Men and women were being thrown headlong down ladders,

against walls and into furniture. The captain's warning to stay away from windows

was forgotten and a group of enlisted men clustered about a porthole to look out.

Then - crash! - a huge sea smashed into the glass, shattering it to fragments. Many

were cut. One man would have died on the spot if a quick-thinking sergeant hadn't

clamped his thumb on the man's severed jugular vein. Beside sewing up this man's

throat, the doctors took seventeen stitches in his face and eleven in his leg. Yes,

the captain had known what he' was talking about!

The sea and wind were now doing their best to tear the lifeboats away and deck

crews worked constantly to keep them securely lashed. I found out later the deck

engineers were out in that storm off and on all night lashing those boats.

Electricians were constantly on the move, taking care of frayed wires and short

circuits. A fire broke out, but was brought under control.

By now the sea had become an inferno minus only the flames. Waves forty feet

high picked us up, and then threw us down and down until we thought we would never

come up again.

The sea had not spent itself when the doctors were called upon to operate. It

meant saving a man's life, and blood plasma had to be administered. (Give a pint

of blood when you can. I tell you in all honesty that it truly saves men's lives.)

It meant operating on a table that was rocking tumultuously, in a room with all

its windows knocked out, by doctors and nurses so sick they could barely hold their

heads up. Yet the anesthetic was given and the operation successfully performed.

. . .

I became acquainted with some of the casualties on the return trip to New York

and I found that those who were the most severely wounded were least inclined to

brood over their misfortune. Most were quite cheerful and happy beyond words to

be going back home. Some who were badly maimed dreaded seeing their families and

friends for the first time for fear of a too-sympathetic reaction. Sympathy is the

one thing they do not want.

I couldn't help but compare my feelings at returning home to the feelings of

those soldiers who were returning as they were. What mental torture they must have

gone through on the return trip - wondering what would await them at home, wondering

if their sacrifices would be remembered in a world quick to forget. I, for one,

won't forget. I'll remember those men to my dying day ....

I have said very little about the nurses aboard the Lady Luck because I wanted

to see how they stacked up at the end of the trip. Believe me, they stacked up all

aces. There's very little bally-hoo about nurses. They do a non-spectacular job

well and that's that, but if the public could see the sacrifices they make, the

backbreaking work they do, the countless odd jobs that keep them on the go at all

hours - well, verbal praise is inadequate. I have seen those nurses so seasick they

could hardly stand up, but it didn't interfere with their administering to the wants

of the wounded. The cheerful smile was still there. The willing hands were still

available. Nothing I can say here can do those nurses justice.

The same goes for the doctors and the enlisted men, too. They worked under the

most trying conditions sometimes, but always quietly and efficiently. There is no

glory in the work they do, only the satisfaction of knowing they are tending to

the humane part of war. And if anyone tells you the overseas medical corps is a

safe outfit - brother, put them straight for me.

I doubt if there is one person who served on the staff of the Lady Luck who isn't

more than a little proud of her. She still is carrying on her work of mercy "over

there." Yes, ladies and gentlemen, I give you a ship small in size but big in deed

- a gallant lady of mercy - the Lady Luck. THE END

The term "fifth column" has its origins in the Spanish Civil War, which

occurred from 1936 to 1939. General Emilio Mola, a Nationalist leader supporting

Francisco Franco's forces, is credited with coining the term. In July 1936, as

his Nationalist troops were advancing on Madrid, Mola reportedly told a

journalist that he had four columns of troops outside the city but also had a

"fifth column" of Nationalist sympathizers and supporters inside the city who

would work to undermine the Republican government from within. The concept of

the "fifth column" became widely known through media reports and was

subsequently used to describe clandestine or subversive groups of individuals

who operated within a country or organization to sabotage it from the inside.

The term gained even more prominence during World War II when it was used to

describe the potential presence of enemy agents and spies within allied

countries.

Posted September 25, 2023

(updated from original post on 7/24/2011)

|

By S/Sgt. John F. Wojtkiewicz W3GJY-W4GQJ

By S/Sgt. John F. Wojtkiewicz W3GJY-W4GQJ  When I reported back to the bridge a few minutes later the captain looked worried.

I soon discovered why. We had, by deft maneuvering, just missed a floating mine.

Not one of the small or medium-sized kind, but a big one. It would have blown the

Lady Luck in half had we struck it. I looked astern through the field glasses and,

sure enough, big as life the mine was floating -in our wake. The horns standing

out on the surface of the mine (its contact points) looked more wicked and diabolic

than those of the devil himself at that moment.

When I reported back to the bridge a few minutes later the captain looked worried.

I soon discovered why. We had, by deft maneuvering, just missed a floating mine.

Not one of the small or medium-sized kind, but a big one. It would have blown the

Lady Luck in half had we struck it. I looked astern through the field glasses and,

sure enough, big as life the mine was floating -in our wake. The horns standing

out on the surface of the mine (its contact points) looked more wicked and diabolic

than those of the devil himself at that moment.