|

January 1939 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

In 1938, Bell Telephone Laboratories,

Western Electric Company, United Air Lines, and Boeing worked together to developed

the first practical microwave radio altimeter for use in commercial aircraft. The

system reported in this 1939 issue of Radio-Craft magazine

is not a radar unit in that the distance is not determined solely by emitting a

signal and measuring the time taken to the target (the ground in this case) and

back again. Rather, the radio altimeter relies on a heterodyned beat frequency generated

between a reference signal and that of the transmitted and received ground-directed

signal. Author Washburn does a nice job explaining the process, so I needn't add

to it. It is interesting to note the statement about the 500 MHz used being

the "highest frequency ever to be used for practical purposes."

New Radio Altimeter Increases Air Safety

News flash: "Wreckage of plane found on side of mountain

by searching party. All aboard apparently instantly killed."

Last month radio helped immeasurably to promote aviation safety. A great laboratory,

a great industrial plant, and a great airline combined to develop, build and test

an altimeter, for use on airplanes, that accurately indicates height above land-level

(including buildings and bridges).

R. D. Washburne

How many times have you read some such tragic report as the above, in connection

with an airplane crack-up on a mountain? Published figures place this general type

of plane casualties at about 50 per cent; imagine it - one-half of all plane crashes

in which, due mainly to poor visibility (fog, etc.) , the "ship" smacked head-on

into obstructions of which the pilot was unaware. Too frequently its passengers

and crew have passed into Eternity.

Achilles' Heel

How could such a catastrophe occur? The motor was working perfectly; the pilot

was experienced and trustworthy; the radio equipment and flying instruments were

in perfect working order - except that the altimeter locked in position by the impact

indicated a height of several thousand feet!

Ah!-There is the answer. Several thousand feet - above sea level... but

the plane was flying in mountainous country and the altimeter did not, could not,

indicate height above land.

The aeronautic-type altitude indicator operates on the principle of the aneroid

barometer. This type of instrument indicates height (altitude) with respect to a

reference level having constant barometric pressure - a condition which is found

only at sea level.

Engineers have worked unceasingly to develop an altimeter that would indicate

height above land with the same or greater accuracy now possible over water (or

land at water-level).

Demonstration

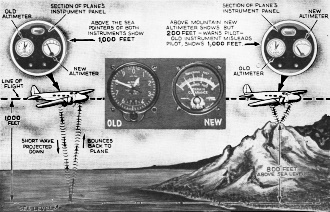

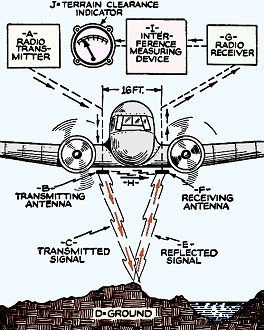

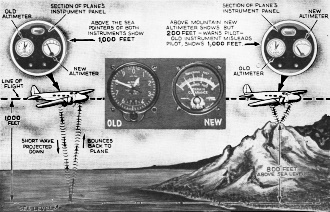

Fig. 1 - Signal C and reflection E, are shown beamed, only

for purposes of illustration. Actually, they are only semi-directional. Antennas

B and F are each 1 ft. long. This radio altimeter is effective from heights of 100

to over 10,000 ft.

Last month radio as shown in the heading illustration solved the problem. The

radio-operated "Terrain Clearance Indicator" proved its ability in direct comparisons

with the Standard Altimeter; the panel meters of both systems were mounted side-by-side

as shown in Fig. A (insert, in heading illustration).

Bell Telephone Laboratories developed this microwave radio altimeter, Western

Electric Co, made the equipment, and United Air Lines installed the apparatus in

a special Boeing twin-engined airliner. In cooperation, these 3 groups demonstrated

the efficiency of the new radio altimeter in a test flight over New York.

Despite weather conditions or poor visibility, the pilot could read his height

directly and accurately whether he was several thousand feet high or merely skimming

a few feet above the earth.

So keen is the sensitivity of the new altimeter that, from an altitude of several

hundred feet, the presence of the George Washington Bridge was clearly indicated

by the meter as the test ship flew down the Hudson River, far above the actual obstruction

itself. Over the Hudson River both altimeters indicated a height of about 800 ft.;

when the plane swung over the Palisades, the standard altimeter continued to show

a height of 800 ft. but the Radio Altimeter indicated the fact that the ground was

only 250 ft. below the plane!

(No comment has been forthcoming as yet concerning provisions for indicating

conditions dead-ahead - an abruptly-rising plateau, for instance - but undoubtedly

means will be found to take care of this condition. -Author)

Extended flight tests of the new development are being made over regular airways

by engineers of Bell Telephone Laboratories in a special Boeing twin-engined airliner

assigned by United for service testing.

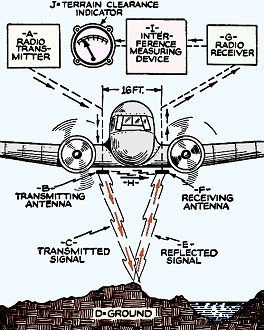

The principle of operation, shown in a general way in Fig. 1, is as follows:

A frequency-modulated, 500-megacycle (0.6 meter) signal - highest frequency ever

to be used for practical purposes, it is said-from a transmitter (A) is radiated

from antenna No. 1 (B) as signal C to ground (D). The reflected signal (E). is picked

up by antenna No.2 (F) connected to a receiver (G).

Although antenna No.1 is directive toward the ground a considerable amount of

energy "slops over" to antenna No. 2 (note direction of arrow, H).

This "slop-over" signal combines with the reflected signal and, in receiver G,

produces a beat frequency which is segregated by an "interference measuring device"

(I) and indicated on a unit, on the instrument-panel in front of the pilot, called

a "terrain clearance indicator" (J).

The beat frequency is a function of the height, .and directly proportional to

it. Therefore the radio altimeter (J) is calibrated for direct-reading in feet.

In order to understand how this radio altimeter functions it may be well to mention

some of the principles previously employed.

Prior Art

(1) The idea of measuring the capacity between airplane and ground is not considered

practicable due to the fact that capacity variation is large for low altitudes but

very small for high altitudes. (2) The principle of measuring the phase difference

between a radiated wave and its reflection is difficult to realize in practice.

(3) The scheme of sending an impulse and then determining the distance as a function

of the elapsed time before the reflection (echo) is received although useful in

measurement of ionosphere heights is not applicable for short distances because

of the minute time element involved. (4). The frequency-modulator radio wave principle

- and the one upon which the new system is based - affords a continuous and linearly

proportional indication of altitude.

Merely to mix, at the receiver, original and reflected signals of the same frequency

(since there would be no change in frequency due to reflection from the ground)

would not produce a beat.

Audio Example

This is easy to understand if we take the example of a person whistling a single

note uninterruptedly. Unless the continuous whistle is interrupted for a certain

length of time it is not possible to hear an echo (reflection) should one exist.

Interrupting the whistle and noting the lapse of time until the echo is heard may

be taken to represent the impulse method of determining distances.

Let us suppose that instead of a continuous single note, a continuous sequence

of notes is whistled. To make the point more clear let us suppose that the note

is warbled up and down the scale, considering however, that in warbling only 2 notes

are sent out.

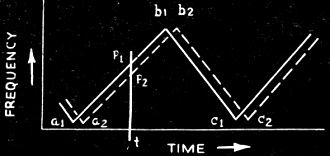

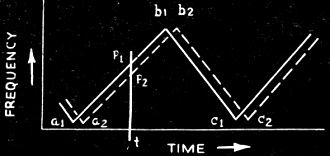

Fig. 2 - The frequency-modulated signal is reflected.

First we whistle note No.1; then, 2nd, note No.2; 3rd, No.1 again; 4th, No.2

again, and so-on. Now, if we are far enough from a reflecting surface so that note

No. 1 reaches our ear as an echo just as note No. 2 is being whistled we will be

able to hear not only both notes simultaneously but also a 3rd or beat frequency

due to the heterodyning (mixing together) of notes 1 and 2. Without going into too

much additional detail let us take for granted that a meter arranged to show the

presence of these beats could be calibrated to indicate the number of feet that

note No.1 had to travel before it heterodyned with note No.2; for maximum indication

on the "beat" meter this will always be a fixed distance.

How then can we obtain beats whose readings on the beat-meter will be equivalent

to other distances?

Frequency Modulation

Well, let us consider a second example in which we wobble the frequency. 5 notes

up and down the scale instead of warbling only 2 notes. The note sequence would

then look like this: No. 1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1-2-3-4-5-4-3-2-1-, etc.

Now, if, at the time note No. 4, let us say, is being sent out, note No. 1 is

received, it indicates that the sound had to travel so far to produce an echo that

a 4-note lag resulted; and since each additional note lag means the sound had to

travel just that much further before the echo could be observed, a "lag meter" indicating

this degree of lag - or difference between radiated and received frequencies - could

be calibrated to read directly in feet distance. This "lag" may be compared to the

"beat" mentioned in the 1st example; the beat frequency (lag) therefore is a direct

indication of the echo distance.

This becomes quite clear upon observing that, when note No.5 is radiated and

note No.2 is being received, there i still a difference of 4 notes; that is, the

echo distance has not changed, hence, the feet-distance (beat frequency) indication

remains unchanged.

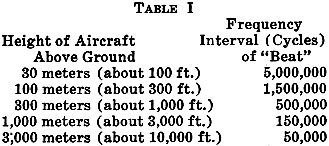

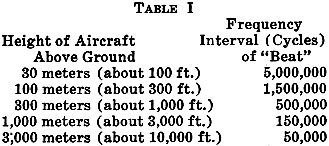

Applying this crude simile to the radio altimeter, let us consider that the 500-megacycle

signal is "wobbled" or frequency modulated. That is, shifted up and down the radio

frequency (wavelength) scale, smoothly and continuously.

The various beat frequencies then required to indicate equivalent echo distances

(or, in the instance of airplane operation, altitude above ground, or a bridge,

a building, or any other reflecting surface) are as given in Table 1. The figures

are from patents issued to Lloyd Espenschied and assigned to American Tel. &

Tel. Co.

With this introduction we are prepared to consider a graph, Fig. 2, which

has been made available by Western Electric Co. This figure illustrates the basic

principle of reflecting a frequency-modulated radio wave (the speed of which is

constant) and indicating the elapsed time as proportional distance.

If an airplane is equipped with a radio oscillator whose frequency can be "wobbled"

according to the sawtooth curve a1 b1 c1 of Fig. 2, and if a corresponding

wave is radiated toward the ground, some of the energy will be reflected back to

the plane where it will set up a current in an antenna. The frequency of that current

will have a similar wobble, but displaced in time to the position a2 b2 c2 by reason

of the delay in travel to the ground and back. At any instant the frequency of the

received wave will differ from that sent out by a constant amount equal to p1 p2.

If the ground falls away or the plane rises, the travel time will be increased

and the received current will be displaced still further; consequently, the frequency

difference at any instant will increase in proportion to the change in clearance.

The difference in frequency between 2 currents can be measured by passing them

through a modulator tube, and measuring the frequency of the "difference" component

in a frequency meter. The scale of this instrument is then graduated in feet, and

indicates directly the terrain clearance.

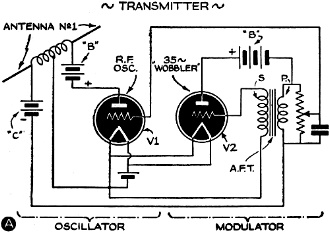

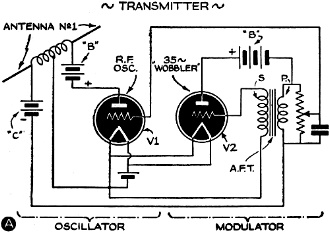

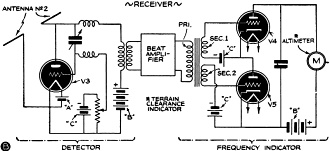

Transmitter and Receiver

Some idea of how microwave signals may be generated and frequency-modulated at

the transmitter, and the reflected and "slop-over" signals received and the beat

frequency detected and made to indicate on a meter calibrated in altitude at the

receiver, may be obtained by reference to Fig. 3. These illustrations are based

in part on figures in an article, by Sadahiro Matsuo (Faculty of Engineering, Tohoku

Imperial University, Sendaishi, Japan), on a radio altimeter, in a recent issue

of Proc., I.R.E.

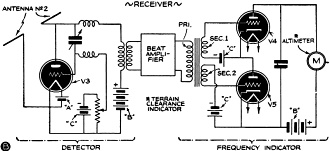

Fig. 3 - (Above & Below) These theoretical, composite

diagrams illustrate the sequence of operations. The frequency-modulated signal results

in a beat frequency that may be resolved on an output meter into terrain clearance

indications in feet.

Referring to Fig. 3A the sawtooth-wave-form modulation, shown in Fig. 2,

is obtained from modulator V2 and applied in required degree to the grid of V1.

(Note - Matsuo's transmitter employed V1 as a Barkhausen-Kurtz triode oscillator.

-Author)

In Fig. 3B, the beat-frequency signal is detected, amplified, limited to

a constant value, and applied to an output meter (altitude indicator). In order

to secure satisfactory operation of an indicator-type frequency meter, with a constant-output-level

beat frequency input, inverse voltage is fed to tubes V4-V5 by connecting transformer

secondaries Sec. 1 and Sec. 2 as shown. Tubes V4-V5 alternate in conductivity.

In addition to the regular meter, the device may also be equipped with a red

signal light which will automatically flash a warning when the plane descends below

a safe predetermined altitude.

This radio distance indicator may also be used on shipboard. In foggy weather

the presence of icebergs, other ships, promontories, etc., could be detected and

their exact distance indicated.

In commenting on this latest scientific tool for aeronautical navigation, W.

A. Patterson, President of United Air Lines, said, "Our engineers and pilots regard

the development of this device as one of the most important technical advancements

in the history of air transportation, and a major contribution to the safety of

scheduled flying. Following completion of service tests now in progress with the

device in United's Flying Laboratory, we will make these devices standard equipment

on every airliner in our fleet."

Posted January 3, 2024

(updated from original

post on 8/12/2015)

|