|

April 1944 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Hugo Gernsback, ever the prolific

author on futuristic technology of the wireless nature, proposes here in a 1944

issue of Radio-Craft magazine a new form of sea-faring weapon that would

project an practically unstoppable assault on enemy ships: a high speed, remote

controlled torpedo*. After being launched from the safety of a location far out

of range of enemy fire, a human controller in an airborne platform (i.e., an airplane)

would, using navigation advice provided by spotter aircraft (forward air

control, in modern terms), steer the explosive craft over potentially long distances

to direct hits on battleships, destroyers, landing craft, patrol boats, etc. Fortunately

for all involved (well at least for

Allied

nations), the war would only last another year and a half by the time this concept

was published so it did not come to fruition in time to test. That would have to

wait for the next war - Korea, a mere five years after the end of World War II.

* A remote controlled torpedo was the basis of

Hedy Lamarr's

frequency-hopping spread spectrum patent.

Radio Motor-Torpedoes

By Hugo Gernsback

The present war has shown that large capital

ships rarely fight it out with other capital ships. The huge monster battleships

are usually held in reserve, wherever possible for the balance of sea-power; they

engage the shores of the enemy rarely. If they do, they must make sure that there

is a sufficient air umbrella to protect them from enemy aircraft. The present war has shown that large capital

ships rarely fight it out with other capital ships. The huge monster battleships

are usually held in reserve, wherever possible for the balance of sea-power; they

engage the shores of the enemy rarely. If they do, they must make sure that there

is a sufficient air umbrella to protect them from enemy aircraft.

No longer are large battleships safe near the enemy shore. The sinking of the

two English battleships - The Prince of Wales and the Repulse - proved this sufficiently

off the coast of Malaya. These two battleships, not having an aircraft umbrella,

were quickly sunk by Japanese torpedo planes. Likewise, the Italian capital ships,

when still under the Axis rule, stayed safely in their harbors and did not venture

forth to give battle to the English and American Navies.

Air power has changed naval tactics considerably, and even if one country has

an overwhelming superiority in naval equipment, this does not make for an automatic

or certain victory, as would have been the case before the advent of air power.

Today, when one naval unit attacks another, a handful of airplanes equipped with

torpedoes can raise fearful havoc with the opponent's fleet. For this reason, it

is safe to predict that future decisive naval battles will be fought without the

two fleets even glimpsing each other. This has already been shown by our own engagements

in the South Pacific with parts of the Japanese fleet, and the tendency will increase

from now on. Whenever we are attacking a Japanese fleet, it will be from a safe

distance anywhere from 100 to 150 miles away. Our Air Force will bear the brunt

of the preliminary fighting. We will try to sink or damage as many of the Japanese

naval units as we possibly can from the air, before our capital ships close in for

the kill.

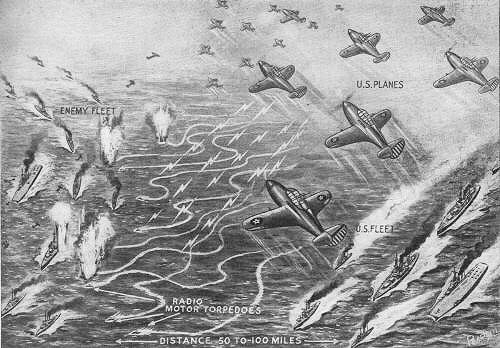

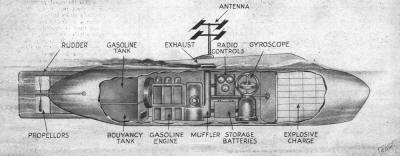

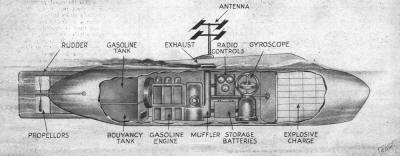

Long distance torpedoes, which are combined with a type of motorboat craft and

which are controlled by radio from airplanes, form the substance of this article.

These radio super-torpedoes have enough fuel to travel over a distance of several

hundred miles in the open sea. Their speed is sufficiently great and the radio control

is such that they they become difficult targets for the enemy.

The present day aerial torpedo, launched from an airplane against an enemy vessel

is a formidable weapon, but if the opposing force possesses sufficient air-power

- that is, fighting planes - it can then down the torpedo plane or planes, so that

the latter never get a chance to come near the enemy fleet.

We need, therefore, something better, and the means which are described here

seem to fill that need.

As is well known, the ordinary torpedo usually is powered by compressed air.

It only runs for a few thousand yards at the most, then if it does not strike its

target, it automatically sinks before it is captured by the enemy, or does damage

to its own fleet. What then is needed is a long distance torpedo which can travel,

if necessary, 100 miles towards the enemy, then if no strike is made, it can return

to its own fleet with, full safety to the latter. For this purpose, we require not

an ordinary torpedo, but rather a sea-going motor speed-boat combined with a torpedo

as shown in our illustrations. In the forward part of the boat is the war-head carrying

several thousand pounds of high explosives, similar to those in regulation torpedoes.

The device therefore is nothing but a super-torpedo, which instead of using compressed

air (or electric batteries, as some types now use) has powerful, standard motorboat

engines. There is also sufficient fuel aboard so that the craft can run up to a'

distance of 200 miles, if necessary.

|

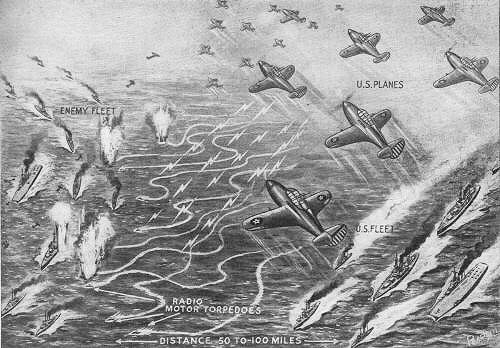

One observer-pilot may handle the necessary controls to keep two or more torpedoes

accurately on their way to the distant target.

|

Like a regulation torpedo, this motor-torpedo carries no one aboard the craft.

But here, the similarity ends. The usual torpedo is launched on its course and then

by means of its gyroscope and other electric devices, it speeds toward the enemy

craft which it usually sinks, or heavily damages, on impact with it. The radio-controlled

motor-torpedo also has its share of automatic devices, but, most important, its

radio "brain" which does the steering has the latest possible refinements, so that

it not only can be made to veer from right to left, but it can suddenly swerve almost

at right angles, cut figure eights, run around in circles, etc. In practice this

radio super-torpedo would work out somewhat as follows:

The motor torpedoes are carried on any suitable naval craft of the fleet. When

ready for battle, they are lowered into the water, the engine is started and, after

short preliminary tests, the craft is sent on its way in the general direction of

the enemy. At the moment the motor-torpedo is started, an airplane which has on

board the radio control which is to guide it, also takes off from its carrier, or

is catapulted from its mother battleship. The torpedo is painted in such. a color

that it is easily visible from aloft. Note that this particular torpedo does not

submerge entirely as does the regulation type. There is, however, very little of

its upper structure visible and its runs almost awash. Most prominent is its antenna

over which it receives the impulses from the guiding control plane.

The motor torpedoes are carried on any suitable naval craft of the fleet. When

ready for battle, they are lowered into the water, the engine is started and, after

short preliminary tests, the craft is sent on its way in the general direction of

the enemy. At the moment the motor-torpedo is started, an airplane which has on

board the radio control which is to guide it, also takes off from its carrier, or

is catapulted from its mother battleship. The torpedo is painted in such a color

that it is easily visible from aloft. Note that this particular torpedo does not

submerge entirely as does the regulation type. There is, however, very little of

its upper structure visible and it runs almost awash. Most prominent is its antenna

over which it receives the impulses from the guiding control plane.

The radio control operator on board the radio-control airplane has in front of

him a keyboard and the other radio transmission devices making it comparatively

simple to steer the radio motor-torpedo from above. These radio controlled war engines

are fast craft, funning over 40 miles per hour, even in a rough sea. For the time

being, enemy is nowhere visible. But in the meanwhile, our reconnaissance airplanes

have already reported the general position of the enemy fleet. The radio-control

airplane therefore knows the exact direction and he will now speed the radio motor-torpedo

in that direction until the enemy fleet becomes visible.

I should mention here that it is quite feasible for one radio-control plane to

direct more than one radio motor-torpedo. As many as three in a group can thus be

guided by a single plane. The observer, anywhere from 5,000 to 20,000 feet up, can

follow the course of the several torpedoes without too great difficulty. If the

weather does not permit it, he will have to come down, so that with his binoculars

he can actually follow the craft's course. He will be greatly aided in this because

the torpedoes make quite a visible wake in the water, which helps him in locating

them.

Automatic or semi-automatic apparatus may assist in the control and guidance

of these super-torpedoes, making it unnecessary for the observer to concentrate

all his attention on one. There is some reason to believe that some kind of automatic

guiding apparatus is already in use on German aerial radio rockets. (See Radio-Craft,

February 1944, page 267, for a note on certain features of these rockets.)

From here on it becomes a battle between the control airplane and the enemy's

air fleet. Naturally the enemy will do all in its power to down the control plane,

if he can do so. Furthermore the radio-control plane, being the driving brain of

the torpedoes, will be sought out by the enemy - if he can find it. For that reason,

it is advisable for practical purposes to employ a number of planes. The enemy therefore

cannot guess which of the planes is the guiding plane. As all of the planes are

fighter planes, the enemy will not find it too easy to single out the one plane

he most wants to down.

It will be of little use for the enemy to try and bomb the motor-torpedoes, for

several reasons. In the first place they travel at to high a speed. Secondly, being

very small targets, it will be practically impossible to make a bomb-hit on them.

But now let us suppose that we have out-maneuvered the attacking enemy airplanes.

It is by no means necessary for the control airplane to get right over the enemy

fleet. There is no such intention. By now our planes, including the control plane,

have risen to a great height and the radio torpedoes are steered on their course.

Remember, they travel under their own power. Our radio control airplane may actually

still be miles away from the enemy fleet. Thus it does not get within the range

of the enemy's anti-aircraft fire, or anywhere near it. If now the enemy tries maneuvering

to evade the motor-torpedoes, our little craft can do likewise, only much faster,

and no matter how fast the enemy tries to turn, the motor-torpedoes can do it quicker,

because they are so much smaller. The radio operator aloft can then steer each torpedo

into the final run where it must hit its target. The control operator can even guide

the torpedoes around the fleet and attack the enemy from the rear.

The objection will be made that the enemy will be certain to bring into play

his full gunfire directed toward any torpedo when it comes within gun range and

try to blow it up before it can strike one of his ships. This is quite true, but

consider that the motor-torpedo runs at high speed and therefore makes a most difficult

target. The radio control operator aloft can further safeguard it by running it

in a zigzag course. This again makes a hit much more difficult for the enemy's

guns, and the chances for the motor-torpedo to strike its target will therefore

be all the greater.

That an occasional gun hit will be made against one of the torpedoes, and blow

it up before it gets near a ship or transport, is a foregone conclusion. Not every

torpedo can possibly hope to find its mark but note that each of the radio-control

planes can guide up to three motor-torpedoes without too much difficulty. It should

also be realized that we will not attack the enemy just with three torpedoes alone.

We may attack with a dozen or more, at .the same time by using a number of radio-control

planes, each operating on a different wave length, for its own flock of torpedoes.

All this is possible and feasible today, with means well known in the art.

As I have pointed out in my former articles* it is almost impossible for an enemy

to "jam" a radio-controlled weapon today. Therefore this means of beating the motor-torpedo

is immediately ruled out.

If all runs well for us, we therefore will be in a position to secure a number

of sure strikes by means of these radio-controlled torpedoes and sink or otherwise

damage the enemy fleet and probably cripple a good many units.

There are a number of other uses for these radio motor-torpedoes, particularly

for night warfare, against harbor installations, etc., which for security reasons

cannot be divulged in this article.

The idea of radio controlled naval craft is by no means a new idea. During World

War I, the English Navy successfully piloted a radio-controlled ship into the harbor

of of Zeebrügge (Belgium), used by the Germans at that time as a submarine

base. This particular craft had no one on board and was guided to its destination

purely by radio into Zeebrügge harbor, where it was blown up and sunk. This effectively

bottled up the German submarines and their outlet to the sea for many months.

*The Radio Glider Bomb, Radio-Craft November, 1943. Radio Pilot Mine Destroyers,

Radio-Craft, December, 1943.

Posted December 28, 2021

(updated from original post on 12/7/2014)

|