|

October 1957 Radio & TV News

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Radio & Television News, published 1919-1959. All copyrights hereby

acknowledged.

|

Audio crossover networks

have the same fundamental mission as RF multiplexer filters in radio systems,

which is to separate and steer specific bands of frequencies into two or more

signal paths. While simple in concept, implementation in hardware can be a major

challenge depending on requirements for channel separation, feedthrough, phase

and group delay, amplitude equalization, distortion, and other factors. This

article discusses some of the decisions used by crossover network designers

when considering where to make band breaks, while leaving actual circuit design

rules to other authors. I built a set of custom speakers many moons ago and

went through the frustrating process of deciding where to place the breaks and

which speakers to use (based on their rated frequency

responses). In the end, I got an acceptable result, but I never was convinced

that all my work - including paying for fairly expensive

(on USAF, A1C pay) coils for the bass part of

the crossover network - justified the trouble. While I appreciate a truly fine

audio system, 'good enough' is a fairly low standard for me when trading off

quality and cost.

Choosing Your Crossovers

What crossover frequencies and circuits should you use in your 2-, 3- and

4-way hi-fi speaker systems?

By Norman H. Crowhurst

When you set out to choose your hi-fi loudspeaker installation, you probably

do not choose the crossovers as a separate entity, it is true. But different

systems offer quite a variety of different crossover frequencies and rates of

roll-off, etc., so you will want to know what it is that governs this choice.

How many crossovers (two-, three- or four-way system), what frequencies are

used for crossing over, and how sharply do the crossovers act are questions

to which each system gives different answers.

How Many?

On the question of how many crossovers, there are two extreme schools of

thought. One of these favors no crossovers at all - a single extended range

loudspeaker unit, that responds to all the frequencies in the audio range. According

to protagonists for this approach, you will avoid all the phase shifts and all

the problems that crossovers "get you into." What you don't avoid, however,

is the problem of getting one loudspeaker unit to respond to a frequency range

covering the ratio of 1000 to 1, from 20 cycles to 20,000 cycles. Even if you

are content with a slightly less ambitious range, say from 40 cycles to 10,000

cycles, this is still a tremendous range of frequencies to cover with one vibrating

system.

To radiate the low frequencies satisfactorily, it must inevitably have a

large surface area exposed for radiation. To radiate the upper end satisfactorily

it must be extremely light and rigid, to avoid the kind of break-up that causes

erratic response to consecutive frequencies.

Another requirement is that it shall not introduce any distortion. If there

is any distortion in the way it handles the lower frequencies with the large

movements they involve, this will also modulate the higher frequencies, besides

causing distortion components to the low frequencies themselves. This intermodulation,

as it is called, gives a "dithery" rendering of programs when low frequencies

and high frequencies occur at the same time, and can be particularly noticeable

on material like organ music.

It is practically impossible to make a loudspeaker unit with perfectly uniform

response over a range of even 250 to 1 (let alone 1000 to 1) and also with absolutely

no distortion, particularly of the lower frequencies. The use of crossovers

proves to be a boon in helping out, both to achieve a uniform frequency response

and minimize intermodulation distortion. This leaves us with the question, how

many crossovers, and where?

Here the protagonists of the opposite extreme come in by pointing out that

serious intermodulation distortion can only appear when more than one octave

is handled by the same loudspeaker. Consequently it would be good to have 10

loudspeaker units, each covering an octave and thus completing the range from

20 cycles to 20,000 cycles. The first loudspeaker unit would cover from 20 to

40 cycles, the second 40 to 80, the third 80 to 160, the fourth 160 to 320,

and so on, up to 20,480 cycles. This would necessitate nine crossovers between

the 10 units.

Of course, there is no comparison between the effect of these two extremes

on the budget requirement. However good a single extended-range loudspeaker

unit is made, it would never approach the cost of 10 separate units, each made

for its own frequency range, with nine crossovers. So it might appear that the

number of crossovers you use depends on your budget. But before our millionaire

readers proceed to order 10-way loudspeaker systems, it should be pointed out

that this extreme is not the ideal either.

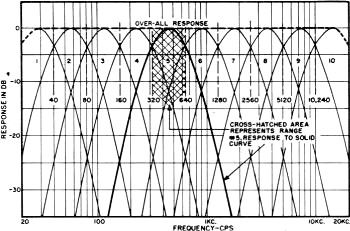

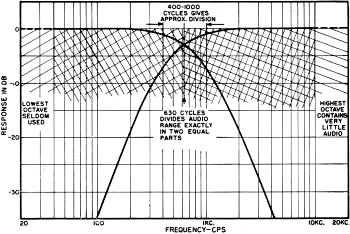

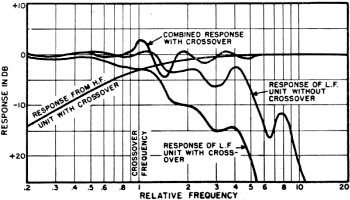

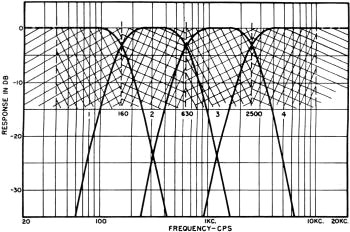

Fig. 1 - Above curves show the division of the entire audio spectrum

into ten octaves. This may be regarded as the very "ultimate" in the number

of crossovers.

While, if well designed, it would certainly do a wonderful job of providing

a smooth frequency response and freedom from IM distortion, this is not all

that is required of a system. In fact, from some aspects, it is not even the

most important thing required of a system.

Smooth frequency response, as measured by steady tone testing, is one thing,

but a smooth frequency response, as judged by listening to program material,

often proves to be quite a different matter. This is because our listening is

much more dependent upon the transient response of the system than its response

to the steady tones used for testing.

If you put a loudspeaker inside the voice box of a pipe organ and opened

all the pipe valves, the frequency response of the system, measured with a continuous

gliding tone, would come out pretty close to flat. But can you imagine what

the loudspeaker would sound like? You've guessed it, like a program being heard

through a mass of tuned pipes. A 10-way system, it is true, would not be quite

as bad as this, but it would follow the same general trend.

Each octave bandpass filter will need to have sharp cut-offs at each side

if we are going to take full advantage of the way this system can minimize intermodulation

distortion (Fig. 1). This would mean that tones in each band would set

up a kind of ringing from the loudspeaker on the particular tone played, caused

by the characteristics of the filter. It is true the "ring" would not be so

pronounced as with a tuned pipe, but it would still result in reproduction with

considerably more coloration than the simpler types of systems despite the fact

that the steady tone response looks flat.

So there are disadvantages to both extremes. As a compromise, most loudspeaker

systems now fall into the two-way or three-way classes, with a few going to

four-way. Having narrowed down the number of crossovers to choose, we can now

take the next question.

Where?

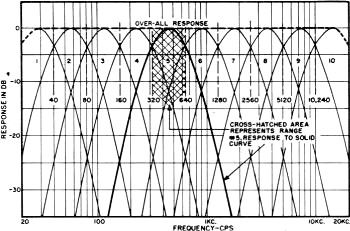

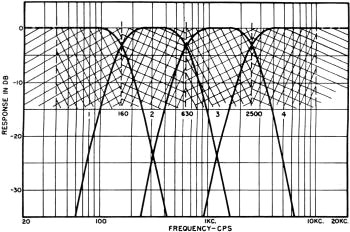

Fig. 2 - When a two-way system is employed. the use of a crossover

in the region of 600 cycles divides the entire audio spectrum into two equal

portions.

If you pick a two-way system, the logical crossover frequency will be somewhere

in the region of 600 cycles. Actually anywhere between 400 and 1000 cycles would

be satisfactory. The reason for this is that, whether you consider you need

the frequency response to be from 20 cycles to 20,000 cycles, or from 40 cycles

to 10,000 cycles, the middle of the range comes out to about 630 cycles. Since

both halves are 4 or 5 octaves, it is not critical, within half an octave or

so, to have the frequency at precisely 630 cycles. Anywhere between 400 and

1000 cycles will divide the spectrum approximately into two equal parts (Fig. 2).

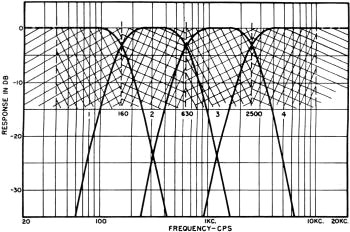

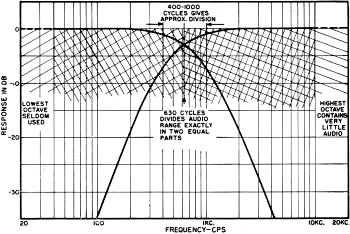

If you take a three-way system and consider the spectrum as extending from

40 to 10,000 cycles, which is more like a reasonable extent, because there is

very little audio "intelligence" in the 20 to 40 cycle range and in the 10,000

to 20,000 cycle range, dividing this part of the spectrum into three approximately

equal parts will require crossovers at 250 cycles and 1600 cycles (Fig. 3)

.

This choice of frequencies brings an interesting fact to light: 250 cycles

is approximately the frequency of "middle C." Frequencies below this correspond

to the bass part of musical reproduction, while frequencies above this correspond

to treble. So this division gives us one band in the bass and two for the treble.

Actually the range from 250 to 1600 cycles could be regarded as the treble,

while the extreme high-frequency range from 1600 to 10,000 or 20,000 cycles

is principally occupied by overtones and transients that provide definition.

In speech the principal components in this top range are the consonant sounds

due to "s," "t," and "d."

Dividing the spectrum four ways would require crossovers at approximately

160 cycles, 630 cycles, and 2500 cycles (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 - If it is desired to divide the more useful part of the entire

audio spectrum into three equal portions, crossovers would be required at

the frequencies of about 250 and 1600 cycles. A three-way system would use

such values.

This consideration has been based entirely on a consideration of the frequency

spectrum. If you consult loudspeaker catalogues you'll find few systems that

conform to the figures just given. This is because there are other factors that

complicate the choice. Wherever you divide the spectrum, by means of a crossover,

the lower frequencies are going to be reproduced by one loudspeaker while the

frequencies above this point come from another. In a musical program, it is

inevitable that the fundamental tones and possibly some of the lower harmonics

of certain instruments will be reproduced by one loudspeaker while other overtones

or higher frequencies will come from another unit. This is one of the undesirable

features of multi-way systems.

Another factor that needs some consideration is the distribution of the dominant

sound energy through the frequency spectrum. This should not be confused with

the apparent loudness of different frequencies. Most curves of average energy

spectrums will show there is not much in either speech or music below 100 or

200 cycles. But here the word average is important, especially for music. .

Bass notes are only evident in comparatively few passages, which is why an average

curve shows them low. However, when low notes are present, they have considerable

energy, and the system has to reproduce this energy - not an average figure.

At the other end, there is not much energy in speech above 500 to 1000 cycles,

but the small energy present is very important to intelligibility, to carry

consonant sounds, particularly "s," "t," and "d." Musical energy, too, tails

off above 1500 to 2500 cycles, except for short bursts from the percussion,

which again do not show up on an average curve. So a system should be able to

handle more or less uniform power peaks over the range from about 40 to 2500

cycles, and should be reasonably flat in response (at lower levels) from 20

to 20,000 cycles or, as a secondary standard, from 40 to 10,000 cycles.

Fig. 4 - With a four-way system, crossovers should be as shown. The

lowest channel would then handle frequencies up to 160 cycles; channel 2 would

cover 160-630 cps; channel 3, 630-2500 cps; and channel 4 would cover all

above 2500 cps.

Consequently a more usual approach is to cover as much as possible of the frequency

range with the mid-range unit. That is, we take as much as the mid-range unit

can comfortably handle without running into difficulties with frequency response

and intermodulation, then the part that the mid-range unit cannot comfortably

handle is delegated, at the low end to the woofer and at the high end to the

tweeter.

Fortunately this integration problem is not very important at the low-frequency

end. By the time you get down to 250 cycles, the wavelength is four feet. As

the biggest loudspeaker system doesn't usually exceed this dimension in one

direction, you are not going to suffer noticeable lack of integration between

frequencies below and above 250 cycles, or any similar crossover frequency for

that matter. So, to maintain good integration, the usual practice is to use

as low a crossover as possible without running into intermodulation problems.

If better integration can be achieved at the high end by pushing the crossover

up to, say 5000 cycles, then we may raise the lower crossover frequency as high

as, say, 600 cycles. Then the tweeter will just handle frequencies from 5000

cycles on up, where the mid-range unit runs into serious break-up problems.

The tweeter will maintain the smoothness of response at the high end.

A crossover around 600 cycles is not likely to run into serious integration

problems provided satisfactory transition is achieved in the 600 cycle region.

More of this in a moment, however. If 600 cycles is the crossover point from

the low frequency to the mid-range unit, the range from 20 cycles, or even 40

cycles, up to 600 cycles is rather wider than any of the other ranges. This

is the reason for going to four-way systems. A unit to handle all the frequencies

below 600 cycles can still cause intermodulation. Such division is not usually

necessary in the smaller living rooms with a well-designed enclosure. Only with

the larger systems, where the low-frequency unit has to encounter considerable

diaphragm movements at the bottom end of its range, is this a necessity to minimize

intermodulation.

How Much?

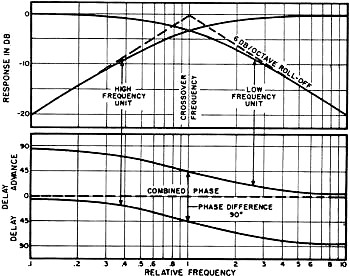

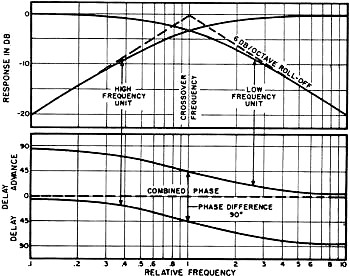

Fig. 5 - Here are the amplitude and the phase response curves for crossover

networks having a 6 db/octave slope. Note that at the crossover frequency

the phase difference amounts to 90 degrees.

So much for the question of the different possibilities in frequency of crossovers.

Next we come to the sharpness of the slope. Different crossovers employ different

degrees of separation between the frequencies. The simplest kind of crossover

uses just an inductance or a capacitance for each individual channel. This provides

an ultimate roll-off of 6 db per octave beyond a frequency of about 2 to 1 each

side of the crossover (Fig. 5).

If the individual units are connected in-phase, so both diaphragms move forward

when the fluctuation from the output transformer in their respective frequency

ranges is in the same direction, the response will come out flat, and the combination

of phase shift from the two will neutralize or cancel, resulting in a uniform

response in frequency and zero phase shift all the way up. Also this simple

kind of crossover does not introduce any measurable degree of transient distortion.

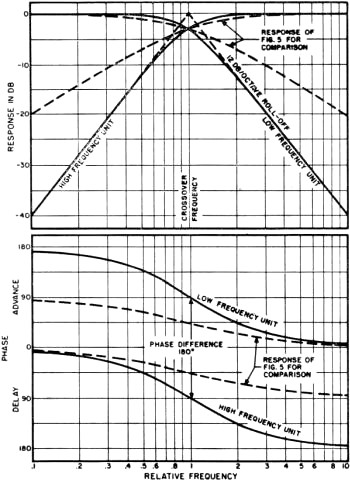

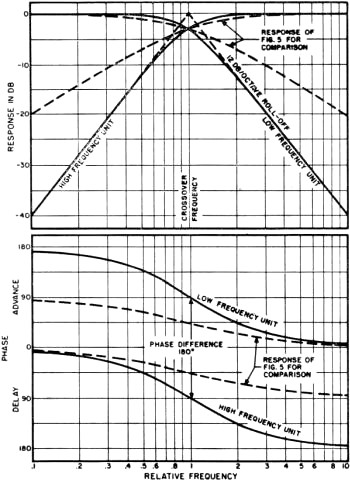

As soon as you get into more complicated crossovers that produce an ultimate

roll-off of 12 db, or more, per octave, there are phase shift problems and also

the transient response is likely to suffer. With a 12 db per octave crossover

(Fig. 6), the two voice coils should be connected in opposite phase, otherwise

at the crossover frequency they will be moving in opposite directions and cancel,

producing a "hole" in the frequency response.

This means that phase reversal occurs with this kind of crossover, through

the transition from one side of the crossover frequency to the other. In theory

this could convert a square wave into a triangular one. But demonstrations have

shown that such a change makes no audible difference. The more important difference

is in transient response. We begin to experience the effect described with the

10-way system. The transition from one unit to the other in the vicinity of

crossover is less likely to be satisfactory.

So why use steeper slope crossovers? The only satisfactory reason is for

minimizing the intermodulation distortion. Another reason that has been advanced

is the possibility of interference between the frequency response from the two

units. This will only occur if the frequency response from one unit becomes

quite erratic immediately beyond the accepted frequency range.

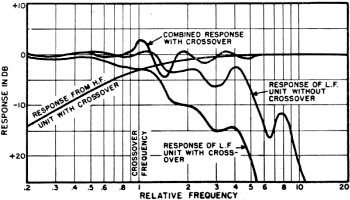

For example, a loudspeaker intended to reproduce up to 600 cycles might show

some erratic peaks and valleys in the region of 1000 cycles. This could seriously

interfere with the over-all response when combined with a separate high-frequency

unit, if the crossover was of the simple type (See illustration Fig. 7).

The answer to this argument is that a unit that becomes erratic in its response

so shortly beyond the accepted frequency range is probably not a very good unit

within the accepted frequency range, although its response may look good. Its

transient response will certainly not be as good as the steady tone response.

Fig. 6 - Relevant details of amplitude and phase response for the 12 db/octave crossover network compared with the 6 db/octave unit (dashed).

Not only does the crossover have to take care of delivering the right range

of frequencies to each unit, with uniform coverage, but sometimes adjustment

for balance is needed too. This is because often tweeters are more efficient

than woofers or mid-range units. If the tweeter unit is twice as efficient,

then feeding it straight-through from the crossover will make the tweeter give

twice the acoustic output it should to maintain balance. To care for this, a

good crossover should incorporate an attenuator, or balance control, so the

output in acoustic watts can be balanced to take care of differences in efficiency

between units.

This brings up another question - what controls to look for on a crossover.

In turn, this could lead into a much more complicated article, because there

is such a variety of ways adjustments can be made; but let's keep it simple.

Only electronic dividing networks have continuously variable controls, either

of crossover frequency or slope of roll-off, and that's another subject. But

some crossovers for use in loudspeaker circuits have adjustments that can be

made in steps, either to change the slope or the frequency. This may be done

by changing capacitor elements, or by changing taps on inductors, or both. If

you buy a unit with these facilities, make sure it comes with sufficient instructions,

so you know exactly what it can do. Don't be satisfied with a vague promotion

statement, such as "this unit is adjustable to suit your system's exact requirements."

Having three or four possible ways of connecting it will probably insure that

one way will sound better than the others, but it does not insure that any of

them are right.

You would do better to buy a unit with only one (right) way of connecting

it, than a "versatile" unit with inadequate information, so you do not know

what each position does. If it comes with complete information you will be able

to check that it does provide facilities for crossing over where you want it

to, and for feeding units at the impedance of your system (4, 8, or 16 ohms).

By and large, then, the recommendation seems to favor using the simpler crossover

and units designed to have a good response, not only within the range for which

they are intended, but also at least an octave beyond the nominal crossover

frequency. Then the over-all response, both to transients and intermodulation

distortion tests, should be quite acceptable.

We have spoken about the question of integration. A few more words of explanation

might be in order here. By integration we mean the radiation of sound as if

the whole frequency spectrum "belongs." This can perhaps best be illustrated

by showing what results without it. If a loudspeaker consists of two units,

say one handling below 600 cycles and the other above, and the low-frequency

unit gives a good smooth response radiated uniformly into the room, while the

high-frequency unit tends to eject its frequencies in a concentrated beam, away

from the low-frequency unit, one can easily get the impression that the high

frequencies in the audio spectrum are "squirted in" as an afterthought from

the side.

This is quite unrealistic on musical reproduction, and on speech it can become

distressing. The principal high frequencies in speech are due to the sibilants,

"s's" and so on. Lack of good integration will give the impression that most

parts of the voice come from the low-frequency unit, while the "s's" are added

from some completely different direction. This is even more unnatural than the

effect on musical programs.

Fig. 7 - These curves show why the response that exists beyond the

accepted range (of the low-frequency unit in this case) can be important to

the system.

To summarize, then, the question of choosing a loudspeaker system and what crossovers

to utilize in it, depends to a considerable extent upon the rest of your system.

If you have a larger-than-average living room to supply with sound, or if

you intend to operate at unusually high levels, with an amplifier of 50 watts

or more, then intermodulation is likely to trouble you, and a three- or four-way

crossover is advisable.

For more average sized living rooms and moderate levels of reproduction,

a three-way crossover will certainly be adequate, and for smaller systems a

two-way crossover is quite sufficient.

The best choice of crossover frequency (ies) and the sharpness of the crossover

is dependent upon the types of units used. While there are broad principles,

based on the frequency spectrum itself, these are modified to a considerable

extent by the effectiveness of the units. In most instances, combinations put

out by a single manufacturer usually incorporate the best crossover frequency

for that combination.

While sharper crossovers have certain advantages in some circumstances, it

is better all round to choose a crossover with a more gradual transition from

one unit to the other as frequency passes through this region.

Fortunately in this branch of high fidelity we find the same thing we find

elsewhere, that paying a lot more for a more complicated system does not necessarily

give us better performance. In fact, if you shop around, you will be able to

find quite a good performing system at whatever price you are prepared to pay.

By paying more you naturally can get a better system, but just paying more and

getting more equipment into the system doesn't mean it must be a better one.

Posted February 25, 2021

(updated from original post on 8/28/2014)

|