|

During and immediately following

World War II, the "Monitoring Service" of the British Broadcasting Corporation

(BBC) relentlessly listened to radio broadcasts from all over the world in order

to be able to break headline news and, if appropriate, pass strategic military information

on to Allied command centers (who were simultaneously doing their own monitoring).

This 1946 Radio News magazine article tells of some of the more significant

messages intercepted and how the facility was a highly guarded secret in order to

prevent sabotage and infiltration. At the height of activity, 32 languages were

being transcribed into English daily, consisting of more than 300,000 words. Voice,

teletype, and Morse code were processed. Rumor has it the propaganda ministry of

Joseph Goebbels is required

study material for modern day mainstream "journalists."

Listening to the World

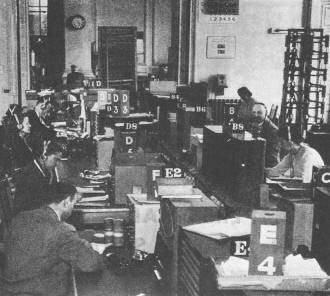

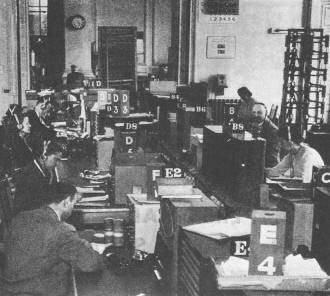

The main listening room in which BBC monitors listen to transmissions

from all over the world, in over thirty different languages. The numbered blocks,

shown in the photograph, are to indicate that a recorder is in use from that listening

position.

By Christopher Cross

BBC's achievements in the development of its famous monitor service -equivalent

to our own FBIS.

When Keren fell, it was the BBC's Monitoring Service that picked up the news

in Arabic from a Cairo transmission and flashed it to Prime Minister Churchill ten

minutes before the operational telegram from the War Office arrived.

When Mussolini resigned it was BBC's Monitoring that picked up the news in Italian

at 22:51 and flashed it to the news department of the BBC at 22:53.

When Holland was invaded, Hilversum was putting out intermittently the announcements

"Parachutists over Parachutists coming down ... " BBC's Monitoring Service got these

messages through to the Air Ministry before the parachutists had even touched the

earth.

Von Krosigk's broadcast announcing the liquidation of the German Eighth Army

was flashed out within six minutes and reached Washington five minutes before the

Associated Press carried the news as urgent.

These are but a few of the achievements of the Monitoring Service of the British

Broadcasting Corporation which, at the time of the German surrender, had developed

into the largest and most efficient listening post in the world.

The location of this service was one of the most closely guarded secrets of the

war. It was in the Oratory School for Boys at Caversham, Berkshire, that John Jarvis,

a blind man with amazing hearing and memory supervised this activity.

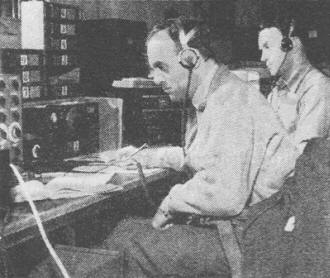

Hellschreiber and Morse Special Listening Section monitors at

work. World-wide transmissions were monitored at all times.

Goebbels' instructions to his network of newspapers and broadcasting

units were tapped by this BBC Hellschreiber machine.

From a few perspiring young men struggling rather on their own initiative to

keep a record of what the enemy was saying, the Monitoring Service grew in five

years to a highly organized professional news and intelligence service comprising

over six hundred employees and listening to every audible broadcast worth mentioning

throughout the world. Before the German surrender it was listening to about one

and a quarter million words a day in thirty-two languages. Some three hundred thousand

words were daily transcribed into English, of which approximately one hundred thousand

were published in a Daily Digest of World Broadcasts, and twenty-five to thirty

thousand a day flashed as an urgent service on teleprinter to 19 War, Government,

and BBC departments. In addition, the daily Monitoring Report, giving the main slants

of world radio propaganda and news and a short daily report for the War Cabinet

offices, were issued. Specialists produced a daily digest in German, French, and

Italian.

The world monitor requires explanation. Before the war there was, by international

agreement, a technical station at Brussels which 'checked on' all wavelengths and

warned broadcasting stations when they wandered too far off their allotted frequency.

This machine was the monitor, Latin for advisor.

Listening in to other nations' broadcasts did actually start in Britain by the

BBC as long ago as the Italo-Abyssinian campaign. But the application of the word

monitor, derived from the Brussels machine, did not occur until the time of Munich.

The Monitoring Service of the BBC did not begin until the late summer of 1939.

The Hellschreiber, a German invention, does for radio what the tape machine does

by landlines. An elaborate Hellschreiber organization was used by Goebbels for service

and instructions to his network of newspapers and broadcasting units all over Germany

and occupied Europe. There was only one way to intercept these messages-by obtaining

a Hellschreiber. The BBC got one, and then more machines. Thus, they were able to

monitor fully both Goebbels instructions and news. At first this was kept secret

since it was not known whether the Goebbels organization knew or suspected that

Britain was eavesdrop-ping systematically on all his private conversations; or whether,

though he knew it, he could do nothing about it since his own Hellschreiber setup

was too valuable and elaborate to be scrapped.

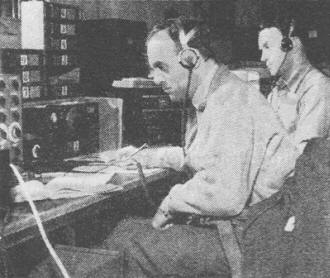

The Morse Listening Room. where ordinary telegraph service signals in Morse code

are intercepted and copied on the typewriters. High-speed signals are recorded and

slowed down later for transcription.

All voice broadcasts are not only heard by the individual monitors (the listeners)

but simultaneously recorded on equipment very similar to that of a Dictaphone, to

insure that what the monitor hears can' be checked. The moment a monitor has finished

his listening and has made such notes as he requires for his own guidance, he goes

into the Information Bureau to confess. This means that he reports every item monitored

to a supervisor who knows where this information should be flashed first. This super-visor

indicates the appropriate treat-ment of what the monitor has heard.

The military leader who said that the BBC Monitoring Service had the value for

the Allied Forces of 40 divi-sions was not exaggerating.

Posted April 26, 2022

(updated from original post on 10/19/2015)

|