|

September 1932 Radio News

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Radio & Television News, published 1919-1959. All copyrights hereby

acknowledged.

|

Being that we are entering

the forest fire season with the onset of summer, this story from a 1932

edition of Radio News magazine is an appropriate recognition of the sacrifice

offered by firefighters who battle the destructive conflagrations.

Firefighters of all specialties have relied on radio communications nearly since

its inception, and particularly once battery-powered versions became available for

portability. It is hard to imagine a time when such a convenience - even a necessity

- was not part of the standard firefighting outfit. Nowadays the radios are compact

and clip onto a shoulder lapel, but in 1932 the vacuum tubes, large transformers

and batteries meant even a primitive radio was in the form of a harness-mounted

manpack

radio (a word not yet coined at the time). The portable half-wave dipole antenna

in the picture looks almost exactly like ones I have seen advertised in

contemporary issues of

QST magazine.

Radio Fights Forest Fire

By George A. Duthie*

The forest Ranger up to this time had to rely upon primitive communication methods

in fighting great fires in our National forests. He has hit the trail to carry word

of a conflagration either by horse or afoot. But now radio comes to the rescue with

two portable transmitter-receivers that contact headquarters within a few seconds

bringing necessary help and equipment in short order

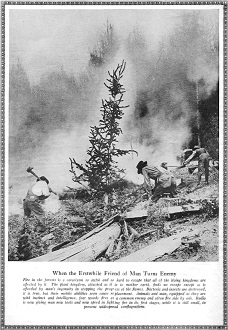

When the Erstwhile Friend of Man Turns Enemy

Fire in the forests is a cataclysm so awful and so hard to escape that all of

the living kingdoms are affected by it. The plant kingdom, attached as it is to

mother earth, finds no escape except as is afforded by man's ingenuity in stopping

the progress of the flames. Bacteria and insects are destroyed, it is true, but

their mobile abilities soon cause replacement. Animals and man, equipped as they

are with instinct and intelligence, fear woods fires as a common enemy and often

flee side by side. Radio is now giving man new tools and new speed in fighting fire

in its first stages, while it is still small, to prevent widespread conflagrations.

Forest Service Photos

Portable radio receiver-transmitters for emergency communication in the national

forests is a recent achievement of the U. S. Forest Service. It is an achievement

hailed with enthusiasm by forest officers. Since the day when the radio telephone

was announced forest rangers have dreamed daydreams of the time when a ranger on

leaving for a trip to the back country, would slip a radiophone into his pack, along

with his grub, and be able to report back to headquarters from the deep woods or

from beyond the high ranges. "An impractical, futile dream," said experts who were

appealed to for help to solve the problem. But the ranger "amateurs" unfettered

by knowledge of radio engineering that recognized this futility, substituted enthusiasm

for learning, and trial-and-error experiments for fundamental research, to achieve

the impossible. The dream has now come true. Its final achievement was marked by

a recent order for the construction of 105 portable and 27 semi-portable radio sets

of a special Forest Service design. It is the first step toward equipping the field

force with this long-sought solution for its emergency communication problems. It

is the culmination of 14 years of research on radio transmitter-receiver sets that

can be carried about in the forests and set up at will for temporary emergency service.

Although both sets are portable radio transmitter-receivers, the smaller instrument

is referred to as the "portable" because it is so light that it can be carried about

in a ranger's back-pack. It weighs only 10 3/4 pounds including batteries and antenna

and is literally a hand radio set which the forester can carry right along with

him as he works (See Figure 1). For the sake of lightness the phone transmitter

is dispensed with and the instrument transmits code only - but it receives voice!

The larger set is called "semi-portable" to distinguish it from the portable. It

is a radio-phone (receiving and transmitting) handling voice as well as code. It

weighs about 60 pounds and may readily be transported any place where a pack-horse

can go.

In the forests the communication problem is present on almost every job. Whether

it is fire patrol or fire suppression, building roads or trails cruising timber,

rescuing lost persons or inspecting range, there is always need for communication.

The work is spread over thousands of square miles of rough timbered territory and

the efficiency and speed with which it is done is directly affected by the efficiency

of the communication system in quite the same way that field operation of an army

depends upon its communication service. Between points of permanent activity, such

as ranger headquarters and lookout stations, telephone lines have already been built.

There are 40,000 miles of government-owned lines in the forests, and approximately

100,000 miles of commercial and private lines, all of which are available for official

use and yet less than 20 percent. of the territory lies within convenient reach

of a telephone line. There are 200,000 square miles of territory without communication

service except by messenger or, temporarily, by stringing insulated emergency wire.

The use of the latter type of communication has been confined principally to

large fires where it has rendered valuable aid, but it is not satisfactory because

it is slow, expensive and generally inadequate. A crew of men will toil for days

to reach the fire camp with an emergency line and the pressing need for it is sometimes

past before it is completed. It is costly because it is difficult to lay down and

maintain, and frequently the wire is not worth the cost of salvage after the emergency

is over. It is inadequate because it furnishes connections only to the supply base.

A wire line cannot be maintained to the rapidly changing fire front where sweating

crews are waging a real battle. It is here that the communication need is most acute,

for the fire fighters may be frantically calling for help but their message will

speed no faster than a runner can travel. The work of the various crews attacking

the fire on several sectors must be correlated, but the officer in charge can receive

his reports and send out instructions only by a messenger who may take an hour (or

many hours) to reach his objective.

The Ranger's Portable Radio Pack

Figure 1 - Special forest service radio pack, weight ten pounds,

range ten miles

Minutes Count at a Fire

The radio solves this problem, for it will move right along with the crews. It

takes but a few minutes to set up the instruments and its message reports the situation

to headquarters at the instant - not the situation as it was an hour or five or

ten hours ago. I have timed a forest officer who, without hurry, unpacked a portable

set, hung up his antenna between two trees, and established communication with a

distant station in twelve minutes. In fire suppression work minutes count and that

is why the radiophone is regarded as an achievement of great importance in forest

protection. The patrolman or the "smoke chaser" hunting incipient fires or the crew

boss on the fire line may now carry his communication with him and contact headquarters

at will (See Figure 2).

How often do small fires become raging conflagrations during the interval while

re-enforcements are being summoned? Perhaps a margin of thirty minutes in arrival

time would have been sufficient to stop the fire in its first run. The portable

set will give the forest officers the benefit of that margin.

Radio will not, however, replace the telephone lines for regular service between

permanent stations. It will supplement the wire system and provide temporary emergency

communication for 80 percent. of the forest territory that is out-of-reach of the

wire lines. The equipment designed by the Forest Service for its work consists of

two short-wave sets; a 3-tube portable for the patrolman's pack, light, compact

and sturdy, which transmits code and receives voice; and a 6-tube semi-portable

set which can be readily transported by pack horse or automobile and which transmits

and receives either code or voice.

The outstanding features of the portable set are its light weight; its compactness;

its simple, rugged construction; and its low cost. These four features, together

with dependable service under the peculiar atmospheric conditions encountered in

forests, comprise the essential requirements that the set had to meet before it

could be adopted. Its power plant consists of a single 140-volt B battery and an

A battery of two flashlight cells which have a life of seven hours. The power of

the transmitter is too small to be measured, but its C.W. range is from 10 to 15

miles - which is enough for its purpose. Exclusive of B battery and antenna, the

entire equipment is contained in an aluminum box 6 by 8 by 9 inches. It weighs but

a trifle more than 10 pounds and can be fabricated for $50.

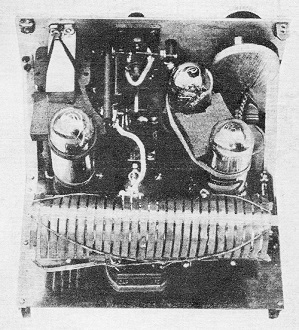

Semi-portable Ranger Set

Figure 2 - Smoke Chaser with Portable Set

This ranger is recording back to field headquarters an incipient

fire by means of the portable set for field use

The semi-portable radiophone (See Figure 3) weighs 60 pounds and has a range

of 10 miles for voice and 20 miles for code. Its power consists of two 200-volt

B batteries and an A battery of three No.6 dry-cells. It is constructed with the

same rugged simplicity as the portable set. While it is too heavy for a man to pack

far over mountain trails, it will stand packing on a horse or by automobile over

rough roads.

The scheme of use for the two sets is to place the semi-portable at the lookout

station, the fire camp or construction camp or any other field job when the short

period of occupancy of the camp and the distance from a telephone line renders wire

communication unavailable. The portables will be carried by the field-going men

who are traveling on foot or by saddle horse. At the lookout station, the radiophone

will act as central station to which the "smoke chasers," who are dispatched to

investigate smokes, will report back with the portable C.W. sets. On large fires,

the crew bosses and patrolmen will carry the portables on the fire line for reporting

to the central camp where a dispatcher will be constantly on the air with a semi-portable

radiophone. A contemplated development for camp set-up is an amplified receiver

which will pick up the signals from the field sets and make them audible without

keeping the dispatcher with his ears glued to the headphones.

The history of the development of this equipment, like that of most new equipment,

has been one of long research, many discouragements, threatened abandonment and

a slow breaking down of the main obstacles and final success in a climax of feverish

enthusiasm. The first attempt to use radio in forest work was made immediately following

the World War with long-wave equipment. It was a complete failure but it served

to discover some of the special problems of radio transmission peculiar to the conditions

in the forests. These problems, for some years, appeared to be insurmountable obstacles

the adaptation of radio to forest communication.

Set-up at Field Headquarters

Figure 3 - This semi-portable radiophone can be carried by motor

or pack horse and set-up in a safe location near the fire to contact rangers on

the fire line.

The Chief Obstacles Were:

1. The absorption of radio energy by the green timber, which to overcome would,

it seemed, require much more power than could be provided in a portable set. 2.

The shadow effects of rough topography. Under high mountains there might be "dead

spots" from which low-power radio signals could not emerge. 3. The deadening effect

of static and fading in the mountainous country, an effect that varies for different

wavelengths and for different periods of the day. 4. The difficulty of erecting

long antennas in the forest where the thicket of undergrowth and swaying branches

of trees would interfere. 5. The mechanical difficulty of constructing a set with

a combination of extremely light weight and the sturdy construction which is necessary

to withstand the hazards of transportation in a wilderness country. 6. Simplicity

of design which will obviate delicate adjustments and tuning so that the apparatus

can be operated by inexperienced and unskilled men.

It would be a simple matter to build radio sets that would overcome any one of

these obstacles, but to successfully meet all of them in combination presented a

discouraging, yes even hopeless, problem for many years.

Following the failure of the first attempt to use radio, nothing more was done

for several years save that some of the more radio-minded members of the service

kept the idea simmering until in 1927, Dwight L. Beatty, an inspector, made some

interesting demonstrations with a small short-wave "bread-board" set which resulted

in his detachment from other duties and his full-time assignment to the radio problem.

Beatty first canvassed the field of commercial sets, especially airplane radio,

but found nothing that would meet the forest requirements. Radio engineers and experts

were interviewed, but they offered no suggestions more than to say that the problem

opened up a field of research in which they could see little opportunity for fruitful

work. It became obvious, therefore, that if radio-in-the-woods was to become possible,

it must come through amateur experimentation.

So Beatty set to work. At the outset, his purpose was to discover the effect

of absorption of radio energy by green timber and the nature of the interference

encountered in the shadow of rough topography. He found that the loss in signal

strength, in timber as compared to an open setting, ranged as high as 35 percent.

He also discovered that the shadow effect and fading in the mountains varied in

wide limits for different wavelengths and that these variations changed during different

periods of the day. For example a 91-meter signal at noon might be completely smothered

but after 4 o'clock it picked up in volume while from the same station a 55-meter

signal which was strong, throughout the day, faded away at night. He found also

that some types of equipment were more sensitive to these effects than others, which

led him into extensive tests of different combinations of parts and hook-ups. He

worked diligently for three years, endlessly building sets, testing them under field

conditions, tearing them down, rearranging and reconstructing, always searching

for improved equipment that would improve efficiency and better provide the specified

qualities of lightness, compactness, strong construction, efficiency of performance

under forest conditions, simple design and low cost. Only standard parts were used

so that there is nothing new about the equipment except its design and assembly.

In each alteration of design greater simplicity was sought. Every dispensable part

was eliminated to reduce weight.

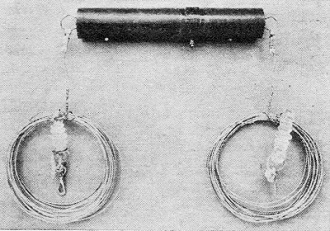

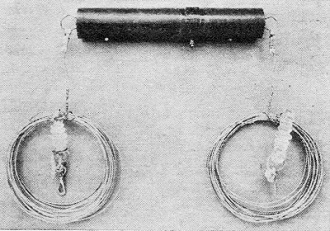

The Power-Feed Antenna

Figure 4 - This antenna was developed for the special use of

the forest service radio-phone.

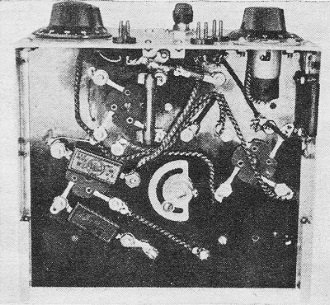

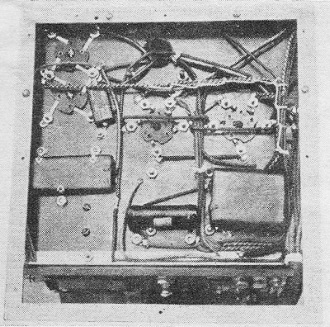

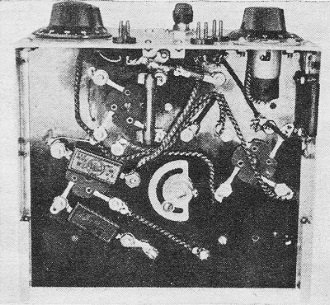

Bottom View of the Two Ranger Units

Figure 5a - The underneath view of the sub-panel of the semi-portable

transmitter-receiver.

Figure 5b - The same view of the portable unit which may be carried

on the ranger's back

By the summer of 1930, Beatty had developed two sets: a semi-portable radio-phone

weighing approximately 80 pounds (including batteries and antenna) and a portable

set weighing less than 20 pounds. The antennas employed with both types were the

same. It was a counterpoise system consisting of an antenna wire stretched approximately

15 feet from the ground between two light masts and a counterpoise wire at 3 1/2

feet, stretched parallel to the antenna wire. The length of the system varied from

73 to 90 meters, according to the frequency in use.

Both sets were given extensive field tests in 1930 in the Columbia forest in

southern Washington. Seven of the portables were placed in service with road and

trail crews and fire patrolmen, and were used throughout the summer. Two of them

were used at the Dog Mountain fire, where a large number of messages were exchanged

during the course of the fire. Although these sets were used by men inexperienced

in radio and without training in the use of code, the records of the use of the

seven instruments showed better than 94 percent successful performance. The 6 percent

failures were due, almost entirely, to weather conditions.

In spite of this good record there were still many problems to be worked out

before the equipment could be voted a success under all conditions. The bugbear

of absorption and shadows had been largely overcome, but the equipment was too heavy

and the aerial too cumbersome. Therefore, when Beatty dropped the work in early

1931 there was grave danger that it would be discontinued. It was rescued from the

discard by F. V. Horton, assistant regional forester of Portland, who put A. Gael

Simson in charge of the work.

Simson was employed in forest research but he was an amateur radio enthusiast,

having served as a radio operator in the Navy during the World War. He was given

two assistants, Harold K. Lawson, a young logging engineer who was employed on timber

sales work and road building, and W. F. Squibb, a student of electrical engineering

at Washington State College, who accepted short-term summer employment as a ranger

guard. All of these men are amateur radio fans. They took up the job where Beatty

left it and tackled the unsolved problems with that intense enthusiasm that only

an amateur knows. Three months after they started work, I happened in at headquarters

one Sunday morning and finding the whole crew hard at work I remarked to Simson:

"Your assistants seem to be pretty much interested in their job." "To a fault,"

he replied tersely, "Lawson, there, is a logging engineer. He thinks the right time

to begin the day is 7 a.m., but Squib is a student; he likes to work at night and

is ready to call it a day about midnight, and between the two they work me a mighty

long shift." So the testing, experimenting, and rebuilding went on, almost feverishly,

throughout the summer. Both sets shriveled in size and weight and increased in reliable

performance. Perhaps the most outstanding improvement, however, was in the antenna.

The counterpoise system was unsatisfactory because it is clumsy and unhandy to

erect. The two wires must be taut, parallel and reasonably level. On rough ground

or in dense undergrowth, finding a suitable place to erect it frequently presented

a serious problem. An opening may be readily found where a single antenna wire can

be stretched where it is quite impossible to find one where two wires could be stretched

12 feet apart in the clear. It was, therefore, decided to make a special effort

to develop a single-wire system and the result is a power-feed antenna of very simple

design (See Figure 4). The length of the antenna is made to correspond to the frequency

of the transmitter. A loading coil, fitted with a terminal attachment for the feeder

wire, is inserted at the correct point to give the best results. This point has

been found to be about 14 percent. "off-center." The coil reduced the length of

the antenna to about 70 feet, which greatly simplifies its erection. Since the point

of attachment of the feeder wire is definitely fixed by the terminal post on the

coil, no particular care in erecting the power-feed antenna is necessary, excepting

to be sure it is in-the-clear of branches or other interference. It has the additional

advantage of being several pounds lighter than the counterpoise system, which is

an important contribution to the success of the project.

The innumerable field tests of the past year have brought a great deal of new

information about the selection of a site for the set-up. It was found, for instance,

that a shift of 200 yards from the base of an overshadowing ridge may increase the

strength of the signals as much as two points in a scale of ten, of which seven

points represent the normal degree of loudness that the receiving operator desires

from a headphone clamped to his ears. Another subject of inquiry was how readily

inexperienced men could be expected to become proficient in the use of the C.W.

portable set. Many of the men who may have occasion to use it will be temporary

laborers, for whom no preliminary training in sending code is possible. It is really

remarkable how quickly untrained men, who may never before have seen a telegraph

key used, can pick up the use of the code. A monitor is built into the receiver

which permits the operator to hear his own signals. This steadies his sending and

provides a constant check on its quality. With a surprisingly small amount of practice

he can send intelligible code signals with the tiny telegraph key. As a final demonstration

test, a young laborer employed on trail construction was given about 30 minutes

coaching and was instructed to send a dictated message. In 46 minutes he set up

the radio, coded the message, sent it to a distant station, had it repeated back

to him by voice, and packed up the radio ready for transportation. This demonstration

silenced all doubts whether the rank and file of officers and temporary employees

would or would not be able to use the C.W. sets without long preliminary training.

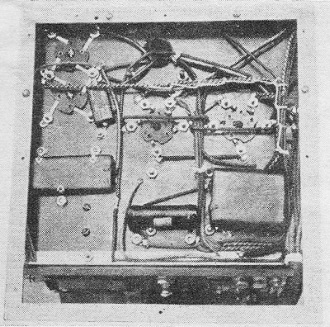

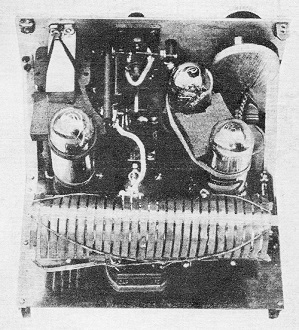

Inside the Portable

Figure 6 - This inner view shows the details of the c.w. transmitter-receiver

illustrating compact arrangement.

If light weight is the first essential, sturdy construction is a second requisite

of almost equal importance. The vibrations, knocks, and jolts of transportation

by truck, pack-horse or man-pack would quickly disable the delicate meters which

are usually considered indispensable in a radio transmitter. All delicate parts

and fragile wiring had to be eliminated to insure dependable performance of the

equipment when it reaches the field. It was found possible to dispense with all

meters (except a small voltmeter which can be successfully cushioned in sponge rubber).

The simple arrangement of the parts, to reduce wiring and strength of all connections,

were worked out with great care (See Figure 5), and the tubes are set in spring

sockets and cushioned with sponge rubber (See Figure 6) so that they need not be

removed during transportation. Both sets have been subjected to every kind of stress

they may meet with in field use and have stood up under the roughest kind of treatment.

Finally the designers decided to give the semi-portable radiophone an accident

test, just to see how much it would stand and where failure might first be expected.

Four of the six tubes were tied to their sockets with rubber, the remaining tubes

were left free. The set was then dropped 14 feet to the ground! The jolt caused

the two free tubes to jump from their sockets and to break. The broken glass was

shaken out of the set, the two broken tubes replaced and it was put "on-the-air"

without further adjustment and a conversation carried on with a station 60 miles

away. The sets have certainly been built for rough going!

The experimental stage is now completed. Every conceivable test for weaknesses

that might develop has been made and as weak points have developed changes were

made to remedy them. Radio is now ready for the field, the forests, and a thousand

ranger officers are reaching for it. Approximately 150 sets will be available this

year, and these will be issued to a few forests where the need for them seems most

urgent and where good opportunity exists for exacting field tryouts. It is to be

expected that some failures may develop, for the sets will be used in every kind

of climatic situation from the humid forests of northern Washington to dry deserts

of Arizona and California, from sea level to the timberline country of the Continental

Divide, in heat and cold and from mountain top to the bottom of deep canyons. Some

situations may be found where special equipment or change of design will be necessary,

but the versatility they have already displayed in experimental tests gives confidence

in their adaptability to almost any situation. Long before sufficient equipment

to supply all of the forests can be had, there will be opportunity to discover any

peculiar situations where special adaptations will be necessary.

A problem which can be foreseen, but upon which no work has as yet been done,

is regulation of traffic in the channels assigned to the Forest Service. When 147

forests are equipped with radiophones and each forest has several central-camp stations

receiving reports from several individuals using portable sets, it can be foreseen

that, without regulation, there might be chaos. The very-low power and range of

the instruments will help to hold this situation in check to some extent, but some

additional regulation will doubtless be necessary so that all the men will not try

to talk at once.

* Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Posted June 28, 2023

(updated from original post

on 7/4/2014)

|