|

April 1935 Short Wave Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from Short Wave Craft,

published 1930 - 1936. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Despite all the prefabricated,

relatively inexpensive products available these days, there are still many people

who like to build their own projects. Whether electrical or mechanical - or both

- some sort of enclosure is usually involved. Often, you can cannibalize an existing,

retired project to use its chassis or find a product at Walmart or a home improvement

store that does not cost too much that you can buy just to get its enclosure. Buying

a pre-formed chassis for your project can get expensive, so there are times when

the best option is to obtain a piece of sheet metal (which can also be expensive)

and bend it yourself. If you have never attempted such an endeavor, believe me it

can be pretty challenging, especially with heavier gauge metal. It is usually best

to lay out and drill / cut / punch / file as many holes as possible prior to doing

any bending. This chassis bending article presents a good method for forming your

sheet metal, but does omit recommending making holes prior to bending - maybe hole

cutting was in the next month's edition. If you need a custom box but do not feel

confident making it yourself, try taking your plans to a heating and air conditioning

shop that does its own ductwork fabrication in-house. Those guys are really good

at this stuff, and you will probably get a better price than going to a machine

shop.

How to Bend Your Own Chassis

|

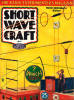

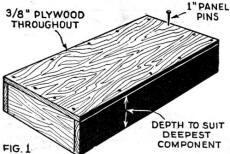

Fig. 1 - Simplest wooden chassis.

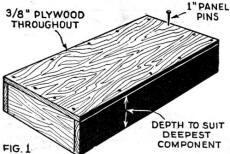

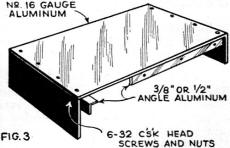

Fig. 3 - Simple design of metal chassis, built up from flat

pieces, without any bending. Angle aluminum or brass, tapped for 6 or 8-32 machine

screws, serve to hold the sections together.

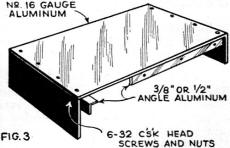

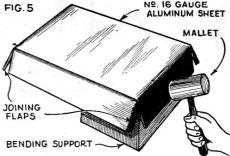

Fig. 5 - The metal, aluminum or steel, is bent by hammering

back and forth along the side to be folded. Don't try to bend it all at once, but

a little at a time along the entire section.

|

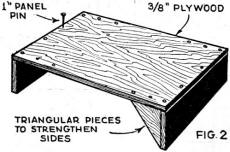

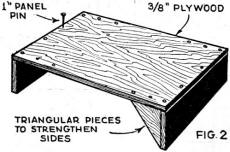

Fig. 2 - More open type of wooden chassis.

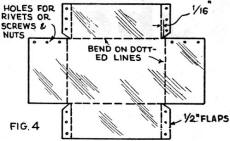

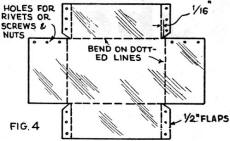

Fig. 4 - Shows how typical metal chassis is laid out before

bending, which takes place along the dotted lines. Flaps are cut out with snips

before bending.

Fig. 6 - Handy way of mounting chassis so it can be rotated

while wiring. Screws permit clamping in any position.

|

To earn the coveted title of Advanced Constructor, you certainly must do something

about set-chassis making. It all depends on how you go about the work. You can with

advantage start off with a really simple wooden chassis, gaining confidence for

more ambitious metal affairs as you construct various shapes and sizes.

Shall we take a look at Fig. 1, for a start? Here is the most straightforward

complete chassis we can imagine. It is made up entirely of wood - preferably treated

wood of the metallized variety. This is available in England, but not here, to our

knowledge. Metal foil or screening could be put over the wood. Tin, zinc or brass

could be used in an emergency.

So that the design in Fig. 1, built up of metallized wood, or metal-covered

wood, is a really sound chassis. Its size depends, of course, on your own needs.

The governing considerations will be the depth - determined by your deepest sub-chassis

mounted component.

You can use 3/8 in. wood for this Fig. 1 chassis, tacking together the top,

sides and ends with 1 inch panel pins (brads). Be generous with these pins, and

then you will have a stout chassis that will stand any amount of knocking about.

If you know that the sub-chassis wiring is going to be rather complicated, or

if there are going to be a lot of components - some being therefore inaccessible

- you might try the Fig. 2 chassis, which is a more skeletonized version.

Tack the top portion to two ends, strengthening up the structure with four triangular

pieces of wood. Use the same wood as before, and the same pins. With a shallow chassis

this method is very satisfactory.

So much for simple wood chassis, which are becoming more popular as amateurs

realize the easy way they can be made up - and as it dawns on amateurs that a good

metallized or metal covered, as explained, wood chassis can do all that a more ornate

all metal job can do.

There are times, though, when a really nice metal chassis is wanted - and then,

assuming you are inexperienced - the Fig. 3 construction is admirable. All

you need are three perfectly flat pieces of No. 16 gauge aluminum, one for the top

and two for the ends. These are then held together by angle brackets, which you

can readily buy quite cheaply - especially in brass. But they are also available

in aluminum if you look long enough.

Now we come to the more complicated sort of chassis - a real all-metal affair.

You can see how it is dimensioned from Fig. 4.

About the bending. This is really quite an art - but an easily acquired one if

you go the right way about it. The first need is a hardwood block to work upon.

It should have true corners - to make sharp bends in the metal when it is hit.

Hit with a wooden or rawhide mallet, too. If an ordinary hammer is used it will

badly mark the metal. You can see how this job is done from Fig. 5.

At Fig. 6 is just a little idea for chassis experiments. Make up a stand,

with two slots in the ends, so that the chassis can be swiveled around - then you

can examine components and get at tricky bits of wiring. -Courtesy English "Amateur

Wireless."

Posted March 2, 2020

(original 1/14/2015)

|