|

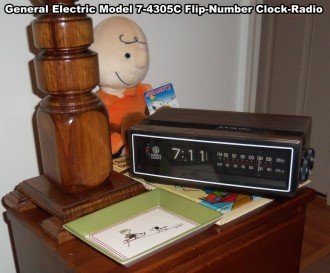

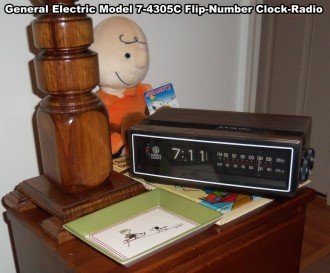

A while back,

I posted information on a vintage General Electric (GE) analog

AM/FM clock radio that I bought on eBay. It is a model I had as

a teenager while living at home. As with most, if not all, AC clocks of the day,

it used a synchronous motor to drive the clockworks - in my case a set of

rotating numerals for displaying the time in increments of minutes (no seconds display).

Synchronous motors, as the name implies, rotates at a rate proportional to the frequency

of the alternating current that drives it. In the United States the AC line frequency

is 60 Hz. In the United Kingdom, the frequency is 50 Hz. Consequently,

a clock designed to work at 60 Hz will run at a rate that is 50/60, or 5/6

the normal speed when operated at 50 Hz. Rather than increment the minutes numeral

once every second, it will do so once every 6/5*60 = 72 seconds. A while back,

I posted information on a vintage General Electric (GE) analog

AM/FM clock radio that I bought on eBay. It is a model I had as

a teenager while living at home. As with most, if not all, AC clocks of the day,

it used a synchronous motor to drive the clockworks - in my case a set of

rotating numerals for displaying the time in increments of minutes (no seconds display).

Synchronous motors, as the name implies, rotates at a rate proportional to the frequency

of the alternating current that drives it. In the United States the AC line frequency

is 60 Hz. In the United Kingdom, the frequency is 50 Hz. Consequently,

a clock designed to work at 60 Hz will run at a rate that is 50/60, or 5/6

the normal speed when operated at 50 Hz. Rather than increment the minutes numeral

once every second, it will do so once every 6/5*60 = 72 seconds.

Why write about that here, you might ask? Well, a few days ago I received an

e-mail from a chap in the UK who bought a similar clock radio on eBay. He told me

of his experience and asked if I knew what was causing his clock to run slow. I

knew it was not due to Special Relativity because he was traveling on Earth at about

the same rate as me - a little slower due to being at a higher latitude - but insignificant

for the reported error) ;-) Once I noted his .co.uk e-mail address, the answer was

immediately obvious.

My suggestion was to find a voltage and frequency converter made for international

travelers. Most of those converters, I warned, convert only voltage but not frequency.

What he needs is readily available, but costs much more, a

dual voltage, dual

frequency converter. It would be cheaper to find a synchronous motor designed

to run on 50 Hz and retro fit it to the clock.

Synchronous motors are uniquely qualified for use in clocks because of their

slavish (electronically) dependency on the line frequency. The long-term stability

of AC power, at least in the U.S. is exceptionally good. Power generation stations

monitor the output line frequency (Brits refer to it as the 'mains') and make occasional

adjustments to bring everything back into sync. Power companies use a highly accurate

Universal Time (UT) reference for comparison for the automated system to make frequency

changes. It is impossible to maintain a constant, highly accurate line frequency

due to load changes, mechanical irregularities in the generation equipment, transmission

routing changes, etc., so metered corrections are used to compensate over time.

A simple formula governs rotational rate of an AC synchronous motor:

Ns = 120 * (f/p) [rpm]

where f = line frequency (Hz), and p = number of poles per

phase. Accordingly, you could build a synchronous motor to drive the minute numeral

changer without using any gears simply by using 120 * 60 / (1/60) = 432,000 poles

;-)

In an August 1964 Electronics World article titled "Frequency & Time Standards," I commented on how much the crystal-driven

digital clock in my high-end, 2014-era Asus notebook computer does a lousy job of

keeping time and how it by default only updates its time with Internet time once

every 7 days. It can easily be off by a couple minutes, which tends to annoy amateur

horologists

like me who have multiple chiming clocks that I keep in synch. Incidentally, I almost

referred to myself as a

chronophile,

but had the good sense to look up the official definition first and discovered the

tern chronophelia, which ain't good. Various sources offer a wide range of definitions,

at least one of which is not complementary. Whew - that was a close one!

BTW,

Wikipedia has a cool set of audio samples of 50 Hz, 60 Hz,

and 400 Hz 'noise' to listen to the difference.

|