|

September 19, 1966 Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Electronics,

published 1930 - 1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

John Mackenzie's 1966

Electronics magazine article predicted a future where glass would

transcend its role as a passive material to become a primary semiconductor for

devices like memories, transducers, and switches. This forecast has proven

remarkably prescient. While crystalline silicon has dominated mainstream

computing, the unique properties of amorphous materials, now classified under

amorphous semiconductors or phase-change materials, have become foundational to

modern technology. The most significant realization of this prediction is in

non-volatile memory, where chalcogenide glasses are the active material in

commercial Phase-Change Memory (PCM) and the memory cells of optical discs

(CD-RW, DVD-RW). Furthermore, thin-film transistors (TFTs) made from amorphous

silicon are ubiquitous in every LCD display, and specialized glass-based sensors

are used in various applications. The author's vision of a "renaissance in glass

technology" has been fully validated, with these materials now performing the

precise "primary roles" he envisioned. Check this 2025 news headline: "Glass

Use in Semis to Triple by 2030."

Looking Through Glasses for New Active Components

John D. Mackenzie, known internationally for his work on glass,

was born in Hong Kong and educated in England. After a postdoctoral fellowship at

Princeton University, he did research at the General Electric Co. and became professor

of materials sciences at Rensselaer in 1963.

By John D. Mackenzie, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy,

N.Y

Renaissance in glass technology is providing hundreds of new

materials - including amorphous alloys - with potential applications as low-cost

semiconductor components, transducers, memories and other devices.

Glass isn't an ordinary electronic material, even though most component designers

only use it in ordinary ways. Many kinds of components, from switching and memory

diodes to computer memories, might be cheaply produced with glass if recent discoveries

by glass scientists were exploited by electronics engineers. Glasses can now be

made as semiconductors, photoconductors, magnets, transducers, optical switches,

memory materials and superior insulators and dielectrics.

Present applications are mainly based on just a few of the obvious physical characteristics

of glass. Most engineers think of it as an easy to form, transparent, nearly impervious

solid with high electrical resistivity. So they use glass for optical parts, tube

envelopes, protective coatings, insulators and substrates. All are secondary roles,

compared with the primary roles assigned to such materials as ferrites and crystalline

semiconductors.

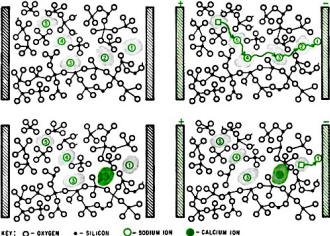

Divalent ions such as calcium improve resistivity of glass by

preventing ionic condition. Weak electrostatic bonds hold monovalent sodium ions

in place (upper left). A direct-current field, indicated by colored electrodes,

causes the ions to move between the glassy chains (upper right). The stronger bond

of a calcium ion (lower left) allows it to block the ions behind it when there is

a d-c field (lower right).

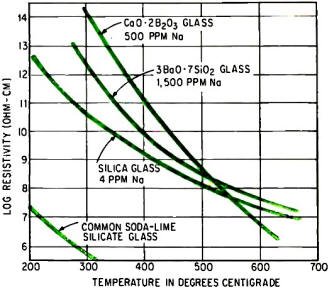

Ionic blocking of calcium or barium ions gives glasses containing

sodium much higher resistivity than silica glass, which is nearly free of sodium

but expensive.

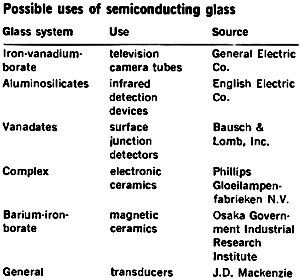

Possible uses of semiconducting glass.

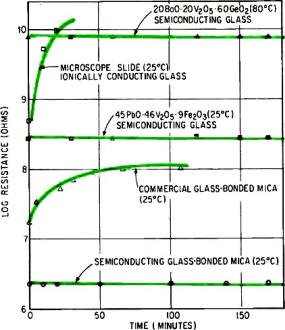

Superiority of semiconducting glass and glass-bonded mica over

ionically conducting materials is indicated by effect of 200 volts of direct current.

Increase in resistance with time indicates deterioration.

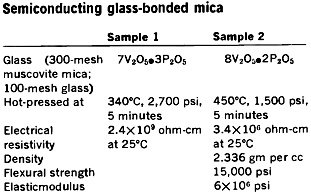

Semiconducting glass-bonded mica.

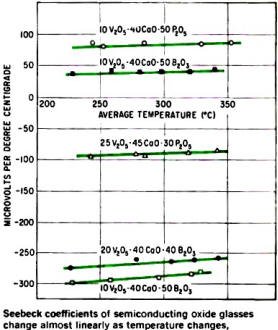

Seebeck coefficients of semiconducting oxide glasses change almost

linearly as temperature changes, indicating they would make good temperature sensors

and thermoelectric devices.

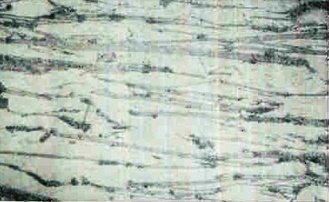

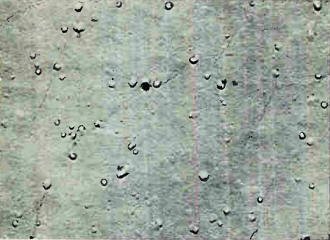

Layered structure of semiconducting glass-bonded mica, magnified

300X. Such high-strength composites can also be made with boron-nitride dielectric

and graphite.

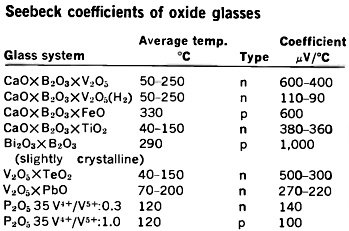

Seebeck coefficients of oxide glasses

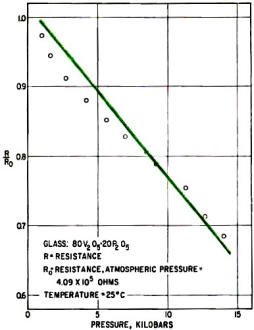

Increasing pressure linearly reduces resistivity of semiconductor

glass, probably because distances between vanadium ions decrease, allowing conduction

to increase. This glass could be used as a pressure transducer.

Semiconducting glass magnified 40,000 times by electron microscope.

"Droplets" are tiny crystals about 100 angstroms in diameter. The size and distribution

of crystals such as ferrites can be closely controlled in glass.

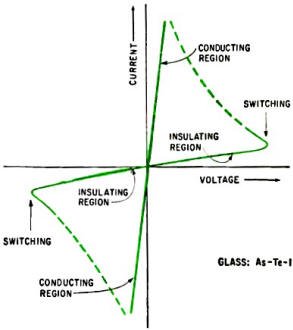

Current-voltage characteristics of diodes made of elemental arsenic-tellurium-iodine

glass. Besides pronounced switching behavior, diodes made of this semiconducting

glass will remember their states for long periods at zero bias voltage.

This general concept of glass as an auxiliary material is actually very narrow

in contrast with the capabilities of hundreds of new glasses. Few people realize,

for example, that glasses are not solids, but rigid liquids that can have an almost

infinite variety of compositions. Their room temperature resistivity can range from

only 100 ohm-centimeters to 10 °, ohm-cm. They can conduct both ionically and electronically.

Their structures can be controlled so that the glassy matrix is host to millions

of ferrite crystals, opening up the possibilities of producing microminiature but

numerically vast arrays of memory elements.

Device designers can't really be faulted for not having exploited these and other

potentially significant features of glass. Materials scientists have still not thoroughly

probed all the inherent electronic properties of glass and some of the glasses that

enhance such properties are new and untried. But it is apparent that glass is enjoying

a technological renaissance certain to make it an increasingly important electronic

device material in the coming decade. Some of the recent discoveries have already

been converted into practical hardware.

Uniqueness of Glass

If device designers are to make maximum use of glass's inherent electronic properties

they should recognize that it is unlike any other material. It can be put to work

both as a liquid and a solid because it is a "frozen-in" liquid. Like most liquids

it can - in the absence of physical disturbances and impurities - be cooled

well below its freezing point without crystallizing. The viscosity of a watery liquid

is 0.01 poise and that of glycerine is 10 poise. When the liquid becomes so cold

that its viscosity has risen to 10 poise it becomes rigid. Such a liquid is defined

as glass. Many materials can be rendered into the glassy or vitreous state in addition

to the common glasses. Since glass is a rigid liquid it never melts but only softens

when heated. This makes the fabrication of glass objects easy and permits materials

to be dissolved in glass at high temperature. The added material can then be precipitated

out in a controlled manner when the glass is cooler and rigid. This explains why

a second phase - such as ferrite crystals of controllable size - can be uniformly

distributed through the glass and why the compositions can be so varied.

The inexhaustible flexibility of composition means, of course, wide flexibility

in properties. In contrast, most solids consist of crystals. Since crystals are

stoichiometry compounds - having fixed proportions - the control over their properties

is restricted. Yet the atomic defects that make crystals so useful in electronic

applications can be duplicated in glass. Glass behaves much like crystal in its

short-range order (over spacings of a few atomic distances). How advantageous this

is, is demonstrated, for example, in the manufacture of high-power lasers. A neodymium-doped

glass laser rod 4 feet long and 3 inches in diameter is readily made by conventional

glass-making techniques. But there is no practical way of making a sufficiently

uniform single-crystal ruby laser of like size.

Glass's fabrication ease should help make practical other new electronic systems,

too. For instance, it is difficult to produce fine, superconducting magnet wire

with adequate insulation. Many years ago glass workers learned to draw hollow, hair-like

fibers of glass by pulling on a softened glass tube. Insulating superconducting

wire can now be made inexpensively by putting a slug of the superconducting metal

into a tube and softening and pulling both at once.

High-Resistivity Glasses

Formulating the glass to suppress ionic conduction improves insulating substrates,

such as those for thin-film circuits. Common oxide glasses may not be chemically

inert to the components they carry because they contain mobile and reactive alkali

metal ions, particularly sodium ions. In silicate glasses, for instance, ionic electrical

transport is entirely due to sodium ions. Their motion deteriorates circuits placed

on the glass.

Using pure silica glass, with a minimum of sodium ions, prevents deterioration.

But such glass is difficult to fabricate, is expensive and its coefficient of thermal

expansion is negligible - too low for good adherence of metal films. However, the

motions of the sodium ions can be suppressed in inexpensive silicate and borate

glasses by adding calcium and barium ions. Ionic conduction becomes negligible despite

appreciable quantities of alkalis. Some newer glasses containing calcium ions are

even much better insulators than silica, as the graph at the right indicates. One

such glass, simply fused wollanstonite, is a silicate of the composition CaO•SiO2.

Because ionic conduction occurs on an atomic scale, it has not been seen visually,

but the mechanism is probably that diagramed at the left. Apparently the sodium

ions must travel in preferential paths, which highly immobile ions such as calcium

can block to pin down the sodium ions.

Normally, the sodium ions are held in place between the silica tetrahedra (silicon

atoms bonded to four oxygen atoms) by electrostatic binding, as in the upper left

drawing. The sodium ions are cations (positively charged) while the oxygen has a

negative charge. However, when there is a d-c potential across the glass, as in

the upper right drawing, the greater attraction of the negative electrode causes

the sodium ion numbered 1 to vacate its original site. Ion 2 can then move through

the opening in the polymer-like chains of tetrahedra and replace ion 1. Ion 3 can

then replace ion 2 and so on until ion 5 has moved along the path.

Sodium ions move easily because their valence is low, only 1, and electrostatic

binding is proportional to the valence, or charge, squared. Calcium and barium are

divalent so their electrostatic binding is four times as strong. The lower set of

diagrams show how a calcium ion - the solid colored circle - stays put in a d-c

field. Sodium ion 1 can still move to the negative electrode but sodium ions 3,

4 and 5 are blocked. This blocking can occur millions of times in a piece of glass,

effectively suppressing ionic conduction and making the glass more inert and more

resistive.

Semiconducting Oxide Glasses

Most polyvalent cations are not only immobile in glass - even at temperatures

of 200° to 300° C - but because they have different valence states they make

possible electronic conduction in glass. Hence, glasses can be semiconductors, often

surprisingly good ones. Some of the possible applications for such glasses are tabulated

at the right. In a crystalline transition metal oxide like iron oxide, electronic

conduction occurs by means of a highly complex charge-transfer mechanism. The mechanism

involves carriers of low mobility, say less than 1 cm per volt-second. Electron

motion in an n-type conductor may be represented by:

Fe2+—O—Fe3+—>Fe3+—O—Fe2+

Electronic conduction can also occur in glass when enough variable valence ions

are present, since the glass's short-range order is considered similar to a crystal's.

Silicate glass containing 10% iron oxide has high resistivity but is also electronically

conducting, so it is a semiconductor.

In glasses the charge transfer is generally called "hopping" and is thought to

be similar to impurity band conduction in doped germanium. This hopping, together

with polarization induced by the charge, is called a polaron, which is now thought

to be the most likely conduction mechanism. In glasses containing vanadium oxides,

which the author has studied extensively, the hopping process is represented by:

V4+—O—V5+—>V5+—O—V4+

Many hundreds of such semiconducting glasses have been made recently. Conduction

is a bulk effect so the semiconductors are not polarized. Resistivity can vary with

the concentration of variable valence ions and other factors.

Semiconductor glasses are superior to conventional silicate glasses for all direct-current

applications. An immediate and important application is improving the long-term

performance of image-orthicon tubes. The targets of these tubes are glass disks

2 to 5 microns thick and about 2 inches in diameter. Their thickness must be uniform

and the glass resistivity should remain at about 1012 ohm-cm at room

temperature. Targets made of common glass deteriorate in time - ionic charge transfer

under the d-c potential of tube operation causes electrolysis. Targets made of the

new semiconducting glass give the tubes long life because the charge transfer is

largely by electrons, not ions, and electrolysis does not occur.

Crack-Proof Dielectrics

Semiconducting glasses can also improve glass-bonded mica, widely used in electronics

because of highly desirable dielectric and mechanical properties provided by the

mica it contains. Unlike ordinary glass, cracks apparently do not propagate through

this composite material, so it can be made into complex shapes by machining or molding.

However, charge buildup during prolonged exposure to electrons leads to dielectric

breakdown. This is due to the ionic nature of the glassy phase. If semiconducting

glass is substituted for common silicate glass, electron conduction overcomes this

difficulty, as shown at the left. Furthermore, the composite's resistivity range,

controlled mainly by the glass phase, is greatly extended.

The layered structure of the mica, as in the photomicrograph at the right, is

probably what prevents crack propagation. Many other inorganic materials also have

a layered structure. Among them are boron nitride, a good dielectric, and graphite,

a good conductor. The author formed composite glasses with both these materials.

They are machinable and possess interesting electrical properties. Varying the amount

of graphite changes the resistivity and its temperature coefficient. The glass containing

boron nitride has very low-loss factors, indicating it would be a superior capacitor

material.

Glass Transducers

Exploitation of glass semiconductors as active semiconductors is still in its

infancy. But it appears that oxide-glass semiconductors could make good temperature

and pressure transducers and that other glasses can be made into switching and active

but nonvolatile memory components.

Many oxide-glass semiconductors have large Seebeck coefficients (a measure of

thermoelectric conversion efficiency), as indicated by the typical values given

in the graph and table at the right.

The graph indicates also that the Seebeck coefficient is relatively stable over

wide ranges of temperature and that the glasses can be made as p-type semiconductors

(upper curves) or as n-type (lower curves). Thus, these glasses might make good,

low-cost temperature sensors.

Another distinction between semiconducting glasses and ionically conducting glasses

is that the electronic conductivity of semiconductors increases with physical pressure.

The resistivity change can be remarkably linear, as plotted by the author in the

graph on page 134. The pressure was applied hydrostatically at room temperature;

at 100°C, the resistance drops about an order of magnitude but is still very linear.

Analysis indicated that the conductivity increase was due to compression of the

glassy matrix, which increased the concentration of vanadium atoms per unit volume

and increased conduction by the hopping process.

An obvious potential use of this glass is as a pressure transducer. Such a transducer

could have advantages over conventional pressure sensors, since the pressure sensed

by a calibrated device could be read directly as a resistance value or used to initiate

a control signal without converting from a nonelectronic value.

Glass Ceramics

Uncontrolled crystallization in glass is undesirable because it makes the physical

properties uncontrollable. However, in recent years the controlled crystallization

of glass has become a highly successful technology with electronic implications

far wider than the present use of the technique to produce supporting materials.

Glass can crystallize because it is a metastable solid - one whose structure

may be radically changed by an impurity or physical disturbance. It tends to crystallize

at temperatures that make the ions sufficiently mobile because the crystalline phase

is invariably more stable thermodynamically.

The glass ceramics widely used in electronics for missile radomes, high-temperature

circuit boards and other components are an example of controlled crystallization.

The insulating types are detailed in a recent book. The crystals, whose formation

is triggered by electromagnetic radiation and heat, are less than a micron in diameter

and closely knit together, so mechanical properties are excellent. They can also

have high electrical resistivity and low loss factors.

Glass ceramics with active electronic properties - such as the semiconductor

glasses - can also be produced today. So it should be possible to further tailor

and enhance their electronic properties.

The composition and hence the electronic properties of such glass can be remarkably

uniform, as evidenced by the electron micrograph on page 135. The picture shows

semiconducting glass in an early stage of crystal formation, enlarged 40,000 times.

The droplets that will later become crystals are only about 100 angstroms in diameter

and the distances between them vary by only a small fraction of a micron.

No such precision can be achieved in formation of single-crystal semiconductors.

If three constituents - call them A, B and C - are combined to form a crystalline

material, A and B will probably concentrate on the surface and C will have a concentration

gradient. The electrical properties will also be nonuniform through the body of

the material, and such factors as variations in temperature coefficient of expansion

may cause strains and other defects.

Glassy semiconductors on the other hand - including the amorphous metals discussed

on page 136 - are almost like perfect single crystals in that there are no grain

boundaries, with attendant faults and concentrations of impurities. This uniformity

might someday be exploited to solve semiconductor production problems. For example,

integrated-circuit manufacturers are beginning to make monolithic circuit arrays

containing thousands of devices on a single-crystal substrate. When crystal semiconductors

are used, the number of devices ruined by random flaws in the crystals pose serious

problems. One such problem is the need to develop custom wiring patterns that avoid

the faulty devices.

New Magnetic Materials

Well on the way to laboratory success is the production of glass ceramics containing

ferrite crystals of controlled composition and distribution. This creates exciting

possibilities in development of microelectronic magnetic devices.

For example, if oxides are melted to form glass with a molecular composition

of 20% B2O3, 30% BaO and 50% Fe2O3,

controlled heat treatment will crystallize barium ferrite out of the glass. Barium

ferrite is a hard, ferromagnetic material, suitable for magnets. Virtually any ferrite

can be produced in glass hosts in this way. Thin films of barium-titanate ferroelectric

have already been made, an achievement that makes possible the manufacture of thin-film

capacitors with high dielectric constant.

From a manufacturing viewpoint, the significance of glass ferrites is the ease

of shaping and "assembling" ferrite elements, compared to the complex sequence of

processes and assembly steps needed, for instance, to produce a ferrite-core memory.

The glass can be pressed, molded, blown or drawn to produce rods, plates, films,

fibers or complex forms. The crystals can be oriented in the glass by controlling

the direction in which they grow. Phosphate glass, for one, contains long, glassy

chains; ferrite crystals will grow along these chains and their easy direction of

magnetization will be along the chains.

Selective crystallization techniques, such as selective heating or irradiation,

can control the location of the crystals. As a simple proof, the author wrapped

a resistance-heated wire around a glass cylinder. When the glass was cooled, the

ferrite appeared as a helix around the cylinder. Perhaps sense and drive wires could

be counter-wound on such a helix by an ordinary coil-winding machine to produce

a small memory. Or perhaps thin-film memories could be made with orthogonal wiring;

if in a forming stage wiring cross-points were heated by an overcurrent so the ferrite

crystallized in the underlying glass film, many of the deposition processes now

required to make planar or laminar memories could be avoided. These possibilities

remain to he proved by electronic device designers.

Optoelectronic Switches and Memories

Controlled crystallization has also led to the invention of phototropic or photochromic

glasses - materials that change color when irradiated by light of one wavelength

and then revert to their original color under light of another wavelength.

Optoelectronic system designers have worked for some time with organic phototropic

materials, but these suffer from "fatigue" - usually, after a few hundred color

changes they lose their phototropy.

Scientists at the Corning Class Works discovered that silicate glasses containing

about ½% of silver halide crystals retain their phototropy for more than

300,000 cycles." Corning is studying the feasibility of using such glasses in optical

displays, temporary data storage and data-processing systems, as well as ophthalmic,

automotive and architectural applications." It might also be used as a Q switch,

a device that boosts the peak power of laser pulses.

The phototropy is a result of glass being a rigid liquid. Silver halide is dissolved

in it at high temperature. After the glass is shaped it is heat-treated at a lower

temperature until the halide crystals are about 50 to 100 angstroms in size. The

glass is transparent to visible light, darkens under ultraviolet light and bleaches

under light of a higher wavelength or when heated. Apparently, darkening results

when the first wavelength releases halogens, but they cannot disperse in the glass

and so they recombine under the bleaching stimulus.

The reactions take from less than two minutes to hours depending on composition

and stimuli, and darkened glass eventually bleaches. Corning scientists concede

slow reactions may bar high-speed electronic applications, but point out that optical

resolution is 10 to 20 times that of photographic film. So they envision other data

and display uses."

Another phototropic glass, discovered several years ago at the Pittsburgh Plate

Glass Co., is based on glass having a short-range order like a crystal12

It has long been known that crystals can be made phototropic by generating color

centers in them. Centers can be formed in glass by melting it under highly reducing

conditions. Doping with cerium or europium ions improves the phototropy. A company

spokesman reported in August that it has not been pursuing electronic applications

of the glass because of the low volume that would be used.

Nonoxide Glasses

A group of glasses known as the chalcogenides now used for infrared transmissions

started with arsenic trisulfide in the early 1950's. The constant hunt for better

infrared transmitters that are more stable at high temperatures led to the discovery

of many such nonoxide or elemental glassy systems. Again, many possess intriguing

electronic properties.

These glasses are made by melting together various proportions of the following

elements: sulphur, selenium, tellurium, arsenic, antimony, thallium, chlorine, bromine,

iodine, phosphorus, silicon and germanium. The melt is quenched to produce the glass.

Some typical glass systems and applications are: As-S-Se, an insulator that melts

at low temperature; As-Te-I, electronic switches and memory devices; As-Se-Te, photoconductor;

and As-Ge-Si-Te, an infrared transmitter that withstands high temperature. Some

elemental glasses transmit infrared light with wavelengths as long as 20 microns.

Recently, the American Optical Co. began making arsenic trisulfide in long fibers

by pulling the melt. This allows infrared light to be piped, as in visible-light

fiber optics, and might pave the way for better methods of transmitting and steering

laser signals.

Some chalcogenides soften at temperatures below 0°C, others are viscous at 100°C,

making it feasible to dip-coat temperature-sensitive devices in glass rather than

organic materials. The softening temperatures can be controlled over a wide range.

Several years ago, Bell Telephone Laboratories reported experimental success

in dip-coating diodes with arsenic and sulfur glasses. They were good insulators

and their chemical stability was superior to organic polymeric materials.18

But according to A.D. Pearson of the research team, that work was set aside primarily

because the planar passivation process for silicon devices proved better. Nonetheless,

glass should be an attractive coating for other types of devices.

Elemental Glass Switches

Current-voltage characteristics of some elemental glasses indicate they can be

used as switching and memory devices. Pearson and his co-workers at Bell Telephone

Laboratories reported on such devices verbally in May, 1962, at an Electrochemical

Society meeting. When point contacts are made to a glass such as As-Te-I, a variation

in applied voltage switches the device from an insulating to a highly conducting

state." The switching can occur in less than a microsecond and is reversible. The

diode would remain in a given state, even under zero bias, and could remember which

state it was in for many days. A generalized current-voltage plot is shown below.

Pearson says this work, too, is inactive at present. One reason is that crystal

semiconductors have better long-term stability and thus are considered more suitable

for telephone system applications. However, several companies in the U.S. and Europe

are actively attempting to develop practical uses for elemental glasses. Little

of this work is reported in the open literature since it is considered proprietary.

[The Energy Conversion Devices Co. disclosed this month that the semiconductor

devices it has begun offering commercially are principally elemental glasses and

amorphous alloys. The active materials are homogenous, without p-n junctions. Devices

being made or under development include a-c and d-c switches, temperature and pressure

transducers, adaptive devices and nonvolatile memory elements. - Editor]

Photoconducting Glasses

The Russians have extensively studied the electronic properties of nonoxide glasses.

One of the better known properties is photoconductivity - the photoconductivity

of glassy selenium, for example, makes it a basic material for xerography.

Glasses based on selenium, tellurium and arsenic are also photoconductors.16

In contrast to crystalline materials, the conductivity of the glasses is insensitive

to impurity contents. This means electronic properties are easier to control during

manufacture. Silicon and germanium are rendered into the amorphous - or glassy -

state by vacuum evaporation and show higher conductivity and other interesting variations

in semiconducting property.' It is not known for certain whether such vapor-deposited

noncrystalline films are glasses. Glasses are usually considered materials made

by cooling molten materials.

Still another new form of glass of interest to electronics is electronically

conducting glass based upon mixtures of oxides and nonoxides."

Quenched and Pseudo Glasses

Quenching and other exotic techniques of producing glasses from metals and other

unusual materials are also being tried. In one quenching technique, called splat-cooling,

droplets of molten metal are sprayed at high speed onto a revolving substrate cooled

by liquid nitrogen. Alloys such as silicon and gold or silver can be made as glass

by this method,18 and some metals that normally will not mix can be rendered

into glassy or amorphous alloys.

The technique is based on the fact that undercooled liquids can be prevented

from crystallizing if the cooling - called quenching - is rapid enough. Since quenching

rate depends upon heat conduction, the smaller the amount of material, the easier

it is to make it into glass. Tiny glass bodies may not interest window and bottle

manufacturers, but small amounts of materials can be highly important in processes

such as those used to produce semiconductor integrated circuits.

Although little information is available on metal glasses, related materials

give strong indications that interesting electronic properties can be expected.

These indications come from noncrystalline films formed by vapor deposition. The

films are not necessarily similar to quenched glass films of the material, but often

they are alike." Silicon dioxide films formed by diverse techniques - such as melting,

vapor-phase hydrolysis, sputtering, thermal decomposition and shock-wave transformation

and neutron bombardment of crystals - have similar refractive indexes and infrared

absorption bands. One can conclude that each SiO2 sample is glass.

If one also assumes that all vapor-formed, noncrystalline films are glass, many

new electronic glasses or pseudo glasses have been discovered in recent years. Among

these are: bismuth, a superconductor; MgO and MgF2, infrared transmitters;

and cobalt-gold alloys, ferromagnetics. The latter should settle the question whether

a noncrystalline material can be ferromagnetic.21

The cobalt-gold alloys were made by researchers at the International Business

Machine Co. They vacuum-deposited the two metals onto a liquid nitrogen cooled substrate.

The material remains amorphous until heated. As it becomes crystalline, its coercive

force jumps, typically from 20 to 40 oersteds. The alloy appears to have a magnetic

structure like fine-grained Permalloy.

It seems, therefore, that microelectronic systems designers searching for new

magnetic materials now have a possible alternative to conventional materials and

oxide glasses containing ferrite.

References

1. J.D. Mackenzie, "Vitreous State," Encyclopedia of Physics, Reinhold Publishing

Corp., N.Y., 1966, p. 769.

2. S.M. Cox, "Ion migration in glass substrates for electronic components. Physics

and Chemistry of Glasses 5, 1964, p. 161.

3. J.D. Mackenzie, "Fine Structure in Glass from Ionic Transport and Volumetric

Considerations," Proc. VII International Congress on Glass, 1965, p. 22.

4. J.D. Mackenzie, "Semiconducting Oxide Glasses," Modern Aspects of the Vitreous

State, Vol. 3, Butterworth Inc., Washington, 1964.

5. J.D. Mackenzie and S.P. Mitoff, "Semiconducting Glass," U.S. Patent No. 3,258,434,

June 28, 1966.

6. J.D. Mackenzie, "Semiconducting Glass-Bonded Mica - A New Electronic Ceramic

Composite," Bulletin American Ceramic Society, 45, 1966, p. 539.

7. P.W. McMillan, "Glass-Ceramics," Academic Press, N.Y., 1964.

8. H. Tanigawa and H. Tanaka, "Studies on Magnetic Microcrystalline Materials

Produced by Crystallization of Glasses in the System 6203-BaO-Fe2O3," Bulletin,

Osaka Government Industrial Research Institute, Japan, 15, 1964, p. 285.

9. A. Herczog and S.D. Stookey, "Glass and Methods of devitrifying same and making

a capacitor therefrom," U.S. Patent No. 3,195,030, July 13, 1965.

10. W.H. Armistead and S.D. Stookey, "Photochromic Silicate Glasses Sensitized

by Silver Halides," Science, 144, 1964, p. 150.

11. G.K. Megla, "Optical Properties and Applications of Photochromic Glass,"

Applied Optics, 5, 1966, p. 945.

12. E.L. Swarts and J. Pressau, "Phototropy of Reduced Silicate Glasses Containing

the 575 m Color Center," Bulletin American Ceramic Society, 42, 1963, p. 231.

13. A.D. Pearson, "Sulphide, Selenide and Telluride Glasses," Modern Aspects

of the Vitreous State, Vol. 3, Butterworth Inc., Washington, 1964.

14. A.D. Pearson, W.R. Northover, J.F. Dewald, and W.F. Peck, Jr., "Chemical,

Physical, and Electrical Properties of Some Unusual Inorganic Glasses," Advances

in Glass Technology, Plenum Press, N.Y., 1962, p. 357.

15. T.N. Vengel and B.T. Kolomiets, "Vitreous Semiconductors," Soviet Physics

- Technical Physics, 2, 1957, p. 2,314.

16. J. Stuke, "Electrical and Optical Properties of Elementary Amorphous Semiconductors,"

Conference on Electronic Processes in Low-Mobility Solids, Sheffield University,

England, 1966.

17. B.T. Kolomiets, "Vitreous Semiconductors," Physics Status Solidi, 7, 1964,

p. 713.

18. W. Klement, Jr., R.H. Willens, and P. Duwez, "Noncrystalline Structures in

Solidified Gold-Silicon Alloys," Nature, 187, 1960, p. 869.

19. D.R. Secrist and J.D. Mackenzie, "Identification of Uncommon Noncrystalline

Solids as Glasses," Journal American Ceramic Society, 48, 1965, p. 487.

20. D.R. Secrist and J.D. Mackenzie, "Preparation of Noncrystalline Solids by

Uncommon Methods," Modern Aspects of the Vitreous State, Vol. 3, Butterworth Inc.,

Washington, 1964.

21. S. Mader and A.S. Nowick, "Metastable Co-Au Alloys: Example of an Amorphous

Ferromagnet," Applied Physics Letters, 7. 1965, p. 57

|