|

October 1968 Electronics World

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Allen Kushner's (Times

Wire and Cable) 1968 Electronics World magazine article portrays

coaxial cables as essential microwave components with impedance, power-handling,

attenuation, time-delay, and shielding traits that must hold steady over broad

frequency, temperature, and harsh environmental conditions like moisture,

corrosion, and flexing. Optimal use demands impedance matching for maximum

energy transfer, minimizing VSWR, radiation losses, and delays; dielectric

selection -- solid polyolefins/PTFE for moisture resistance versus low-loss

foamed or air-spaced types with aluminum sheaths reducing attenuation by 20%;

and superior shielding, from ~80 dB in single-braid to 110-plus-dB in doubles,

triaxials, or sheathed cables. Electrical length, tied to propagation velocity

(66% polyethylene, 81% foam), shifts with temperature (±1°), flexing, and

frequency, critical for phased arrays. Mechanical compromises include stranded

conductors for flex life (20% higher loss), tensile strength enhancements,

moisture-proofing via pressurization/flooding, silver cladding for GHz

stability, and precise, tested connector terminations avoiding soldering

pitfalls. Coax excels in broadband efficiency; consult MIL-Handbook-216 for

details.

Characteristics & Parameters of Coaxial Transmission

Lines

Table 1 - Characteristics of RG/U Transmission

Cables.

By Allen M. Kushner

Manager, Engineering Services, Times Wire and Cable Co.

Coaxial cables are in every sense microwave components. They have an impedance

characteristic, power capability, and a distortion requirement.

transmission line is not just a piece of hardware; in reality it is a microwave

component. It's not merely a cable which links two black boxes but a device with

an impedance characteristic, a power - handling capability, an attenuation or distortion

requirement, a time -delay characteristic, and a specific ability to provide electromagnetic

shielding. In addition, coaxial cable must demonstrate these properties over wide

frequency and temperature ranges without significant degradation due to exposure

to moisture, corrosive environments, and mechanical abuse. Coax is not always the

most efficient means of power transfer; but it is easy to handle and is effective

over wide bandwidths. A valuable feature of coax is that the outer conductor also

acts as a shield.

To achieve maximum efficiency from coaxial cable transmission lines, the engineer

must concern himself with: impedance- matching cables to the system or systems to

assure maximum energy transfer; energy-loss or gain by radiation or pickup; insertion

losses; and time delays. Mechanical considerations enter into his deliberations

since tension and frequent flexing cause insertion losses, voltage standing-wave-ratios

(v.s.w.r.) , and time delays to vary. Temperature and pressure in high altitude

and underseas applications also affect insertion loss and power- handling capability:

while exposure to moisture and chemicals influence cable life.

Dielectrics

Fig. 1 - Cable losses due to dielectric configurations.

The dielectric is normally a polyolefin, polytetrafluoroethylene, air, or some

other substance. While air has excellent electrical characteristics, it is adversely

affected by moisture and it does not provide the necessary support to maintain the

center conductor in place with respect to the outer conductor. For a cable to have

stable electrical characteristics, both factors must be kept constant. Solid dielectrics

are not affected by moisture. they are easily bent without changing conductor spacing,

and they are not affected by changes in ambient pressure. Offsetting these advantages,

however, is the fact that solid dielectrics have the highest electrical losses (Fig.

1). Foamed-plastic dielectric is an effort at compromise between the solid-dielectric

approach and the air-spaced cable. In foam-plastic dielectrics, a great many small,

individual air spaces are obtained by releasing gas in the molten plastic during

the extrusion process. But foamed dielectrics can absorb moisture and cause an increase

in attenuation. This can be prevented by encasing the cable in a seamless aluminum

tube. By doing so, a 20% or greater reduction in attenuation is achieved over ordinary

solid -dielectric cables. It is apparent that we can reduce the attenuation even

further by removing as much solid- dielectric material as possible, leaving only

the amount needed to support and protect the center conductor. Cables housed in

a seamless tubular aluminum sheath with the center conductor supported by minimum

solid dielectric have the lowest possible losses for a given cable size. These sheathed

cables are classified as semi- flexible since they may be easily bent for installation

but not flexed in use.

Fig. 2 - In coax cables, electrical length changes with temperature.

Some cable lengths will vary as much as 1°.

Electrical Length

Usually electrical length is not a crucial dimension but there are applications

where the length of a coaxial cable is critically related to other elements and

to the system as a, whole. Phased array antennas, for example, are functionally

dependent on the electrical lengths of their various electrical members.

Time-delay and electrical length are closely related and for many applications

the engineer must know the mechanical length of the cable and the velocity of propagation

of an electromagnetic wave through the cable (Fig. 2). Velocity is a function of

the dielectric material. For example, solid polyethylene dielectric propagates at

66% of the velocity of light, solid Teflon 69.4 %, and foamed dielectrics at 81%.

Air-spaced cables vary somewhat with velocities of propagation from production run

to production run. In solid-dielectric cables, variances of ±1% are usual;

foamed dielectrics ±2% and air-spaced cables ±2%.

Electrical length also changes with cable flexing and frequency. The variation

from a normal linear response can be ±1% in short cable lengths, but significantly

higher where electrical-length spikes (variations at specific frequencies) occur

in long cable runs.

Shielding

Energy pickup and leakage relate to the quality of the cable's shielding. It

is important that engineers know how much energy is lost through radiation and how

much is picked up from outside sources (interference). The specific application

will, of course, spell out tolerances. For example, consider two N-foot lengths

of single-shielded coax cable side by side. A one-volt input to one cable will result

in approximately 10-4 volt induced in the second cable. This represents

an over-all attenuation from cable to cable of 80 dB. This is only an approximation

since much depends on the type of installation and surrounding conditions. But it

is certainly a correct order of magnitude. In many systems, this much pickup is

considered intolerable. Sensitive systems. therefore, use a second shield, triaxial

cable, or a semi-flexible cable (aluminum sheath).

Fig. 3 - Relative shielding efficiencies for various cables.

Fig. 4 - Variation of v.s.w.r. with frequency. Narrow v.s.w.r.

spike (2.11 was caused by bending the cable).

Fig. 5 - Impedance changes along the length of a cable.

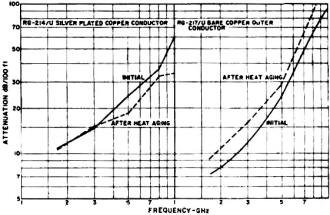

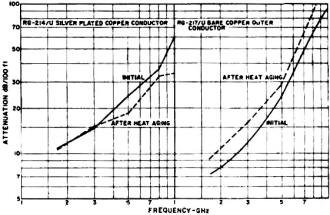

Fig.6 - A stability test of RG-214/U with silver-clad outer conductor

and bare copper-covered RG- 217/U.

Double-shielded cable generally adds about 15 dB more isolation; and triaxial

cable about 15 dB more than the double shielded. Cables encased in seamless aluminum

sheath are at least 80 dB better than the single-shielded flexible variety. The

seamless metal sheath effectively stops energy from escaping or being picked up,

except at the connector interface (Fig. 3) .

Cables must also match the impedances of the "black boxes" they connect. Compatible

characteristic impedances mean efficient transfer of power, no overheating, and

no voltage breakdown. Characteristic impedance is a function of conductor size,

dielectric material, and form (solid, foam, air); and uniformity of dimensions and

velocity of propagation. A 0.1% impedance variation every 3 inches.

The Mechanical Environment

The mechanical environment in which a cable must work is also important in its

selection by the designer. A cable chosen solely for electrical characteristics

may be highly unsuited for its intended environment; and one picked for environment

may have poor electrical characteristics. As it is with most engineering solutions,

the result must be a judicious compromise between function and cost. For example,

when a flexible cable with a solid conductor is attached to a shock-mounted piece

of equipment or otherwise exposed to frequent motion. A stranded center conductor

could be substituted. Characteristically, the stranded conductor will have a much

longer flex-life than the solid, but the stranded conductor will have a 20% higher

attenuation characteristic. The stranded conductor, however, is obviously the only

practical approach and represents good engineering compromise.

Tension

Past installation practices generally account for cable design characteristics

such as tensile strength. Cables of less than 1/8-inch diameter will usually break

at about 100 pounds. Sometimes coaxial cables are used to support a component, in

which case a strength member, such as a reinforced center conductor, a rated metallic,

Dacron, or fiberglass member, is added. Usually, the limitation in cables over 1/8

-inch diameter is the method of cable termination.

Moisture and Temperature

Moisture affects the attenuation stability of cables. In a 1000-foot cable run

it is reasonable to expect one or more pinholes which admit water vapor. Even if

there were no pinholes, water vapor might enter the cable through the connector

and condense. In the ground, borers or worms may attack the cable jacketing and

thus permit water to be admitted. If the dielectric is foam. water vapor will cause

an attenuation increase; and if it is solid, the water will eventually corrode the

braid or short the connector. Underwater, the problem is even more severe because

pressure can push the water through the entire cable length.

Cables sheathed with seamless aluminum are less affected. Sheathed cables that

use an air dielectric and a spline construction to protect the center conductor

may be pressurized to prevent moisture entry. As long as the cable pressure is higher

than the ambient pressure, the conductors will be immune to moisture and corrosion.

New techniques developed for flexible and semi-flexible cables permit flooding the

outer conductor with a corrosion prevention compound which does not affect the loss-characteristics

of the cable. Since flexible cable jackets are not absolutely impervious to ambient

moisture, corrosive vapors may also penetrate them and cause an in- crease in electrical

losses with time. Flooding the outer conductor with a moisture-proofing compound

is a good solution to this problem. Even aluminum-sheathed cables buried in the

earth or otherwise subjected to corrosive ambients must be protected. Standard practice

has been to extrude polyethylene jackets onto the aluminum sheaths. In a -new manufacturing

technique, an additional corrosion preventative layer is added between the sheath

and the polyethylene jacket.

Elevated ambient temperatures may cause a permanent change in loss-characteristics

by oxidizing the outer conductor. Therefore. attenuation in cables using bare copper

and tinned copper conductors increase appreciably at frequencies above 1 GHz. Silver

cladding of conductors brings attenuations down to acceptable levels (Fig. 6).

Impedance and Mechanical Environment

Even when the environment does not affect the cable proper, it may affect the

cable-to-connector junction. The cable must at all times remain in intimate contact

with the connector interface. Tension, flexure, temperature variations -all tend

to destroy the contact. Temperature variations often cause some motion or shrinkage

of the dielectric. Any such internal motions cause the cable-connector impedance

and losses to vary. Sometimes, this kind of situation can go to extremes. A slight

motion can. in certain cases, cause a v.s.w.r. of 3.0 and an increase in attenuation

of 6 dB. These effects are most pronounced at the higher frequencies where a few

thousandths of an inch of motion can mean significant alterations of cable characteristics

and therefore significant changes in system performance.

Cable Terminations

All cables must be terminated in some manner. But the manner of termination becomes

extremely important and relevant to system operation at frequencies about 1 GHz.

Above this frequency, connectors of some kind are employed. But all the factors

previously outlined or mentioned as leading to effective, efficient, and economic

cable operation may be lost by use of an improper connector or by an improper termination

procedure.

Center conductors are normally soldered and sometimes. depending on application,

crimped. The UG V-type of braid clamp is usually a part of the outer conductor;

or it may be crimped or restrained between the two surfaces of a friction clamp.

When using the UG -type clamp, care must be taken to form the outer braid over the

clamping ring and to torque the back nut up snugly. With crimp-type devices, the

crimp ring location is critical to both the attenuation and v.s.w.r. stabilities

of the cable. Center conductor soldering is not really desirable because low temperature

dielectrics (such as polyethylene) can over- heat and alter the relationship between

inner and outer conductor at the connector interface. The cable must seat perfectly

in the connector to achieve the designed electrical characteristics. If seating

is off by as little as 20 to 30 thousandths, v.s.w.r. at high frequencies may increase.

Also, above i GHz, cold-solder joints wreak havoc with cable parameters.

There is increasing recognition of the importance and critical character of the

interconnecting cable and its termination. The sophistication of the "black boxes"

of today is too high to be sacrificed by an inadequate means of energy transfer.

There is a trend, therefore, to purchase cable assemblies which have been fully

tested for insertion loss and v.s.w.r. over the usable frequency range. Cable manufacturers

have developed semi-automated techniques that replace the normal soldering processes

as well as the UG -type of clamp and hand tools used in crimping operations. Many

types of connectors are now being assembled to cables in a true precision machining

process and, in most cases, each and every complete assembly is evaluated by vigorous

tests over its entire specified performance range.

Like so many other engineering areas, the design, manufacture, and application

of coaxial cables has risen to the level of an independent technology. Nevertheless,

it is still difficult to obtain enough cable design information to fully satisfy

design needs. One of the best sources is MIL-Handbook-216, available to companies

working on military contracts. Manufacturers catalogues are also excellent sources.

Some cable fabricators issue technical memoranda from time to time which amplify

specific topics of interest to cable users.

* The author holds a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering degree from Rensselaer

Polytechnic Institute and a Master of Science degree from the University of Connecticut.

He is a former research worker for General Motors and also served with the U.S.

Air Force as an Electronics Officer.

|