|

June 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

In 1969 when this article

appeared in Electronics World magazine, laser technology was still

in the realm of rare earth elements and bulky gas chambers with monster power

supplies. Efficiencies for conversion of input line AC power to output laser

light power was measured in the low single digits. Real science was a long,

long way from the predictions of science fiction in terms of size and capability

of lasers. Although laser technology has made much better progress than futurists'

visions of flying cars and nuclear fusion power generation, we are just now

deploying the first serious laser weapons. Semiconductor-based lasers have

enabled incredible advances in local communications (i.e., point-to-point

optical cable and through-the-air data, storage media R/W, computer mouses[sic])

and physical processing (i.e., etching and cutting), but Earth orbit-to-ground

links are in the early stages of implementation and testing. Reading articles

like this gives you a real appreciation for the people who relentlessly push

the frontiers of science forward.

Experimental Laser Engines

By L. George Lawrence By L. George Lawrence

Future space vehicles may be propelled by lasers that can produce immense

shock waves in the vacuum of outer space.

Although lasers have been thought about and used in areas of communications,

medicine, and metallurgy, the idea of using them as prime movers for space

vehicles is unique. What makes the laser so attractive to propulsion engineers

is its inherent ability to develop immense shock waves and light-pressure

phenomena of considerable magnitude. Research in this area is continuous,

and both theoretical and practical findings permit hopes for the not-too-distant

future.

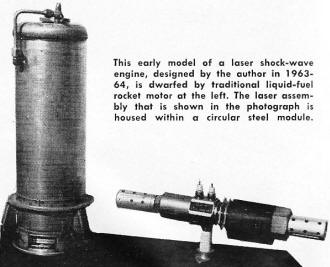

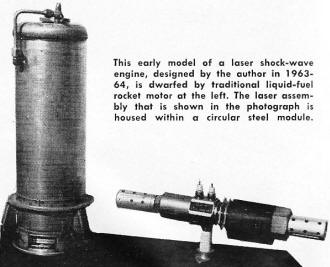

This early model of a laser shock-wave engine, designed

by the author in 1963-64, is dwarfed by traditional liquid-fuel rocket motor

at the left. The laser assembly that is shown in the photograph is housed

within a circular steel module.

Fig. 1. Electrostatic ion engine, although functional,

has very low efficiency. Neutralizing filament is used to prevent collection

of electrons on vehicle, building up negative charge which slows down positively

charged ion exhaust stream.

Fig. 2. Laser light-pressure engine can produce tremendous

radiation pressure; however, the target plate is destroyed.

Fig. 3. Laser engine test assembly that has been

employed for investigating shock waves generated by means of plasmas.

Laser engines, taken together, fall into the classification of electric

propulsion systems. Related thrusters, as exemplified by the contemporary

ion engine, are not a distinctly new concept. One of Dr. Werner von Braun's

teachers, H. Oberth, discussed these systems as early as 1929. Not, however,

until shortly before actual space flights did serious development of the associated

technology begin.

Fig. 1 illustrates one of a family of electronic thrusters. The processes

integral to the engine's function are: (1) generation of charged particles,

(2) their acceleration, (3) deceleration, and (4) neutralization of the ion

beam by electron addition; this latter process being required to restore the

(positive) ions to electrical neutrality by replenishing them with lost electrons.

Otherwise the electrons will collect on the vehicular system, building up

a negative charge that will slow down the positively charged exhaust stream.

A "hot" filament serves as an electron injector.

Much energy is lost during operation. The efficiency of ion engine is very,

very low - something on the order of 50 kilowatts of electrical energy is

required to produce little more than one pound of thrust.

It is no coincidence, therefore, that more efficient propulsion methods

are being sought. Thoughts have turned to all-nuclear engines. But, to date,

no electronics-based nuclear engine has emerged. Nor do we yet have a genuine

anti-gravity device. And the true electromagnetic space ship, much speculated

upon by science-fiction writers as being the best of interstellar vessels,

does not exist.

A laser-type engine's most noteworthy features for propulsion purposes

are light-pressure generation and the ability to produce shock waves. We shall

examine these properties individually.

Light-Pressure Generation

Most of us are familiar with the fact that moving air or water has momentum

when striking an object at a certain velocity. Both streaming jets of air

and water can drill a hole if these streams are powerful enough. But not so

well known is the fact that electromagnetic waves may also have momentum.

They are able to exert "radiation pressure." In the case of objects that are

hit by light, a definite mechanical force can be imparted to the object. The

effective force is, however, very small indeed.

A different situation arises, however, if laser-generated light is point-focused

upon a substrate acting as a light-pressure cell.

By using an experimental system like that shown in Fig. 2, it is possible

to generate a very powerful, coherent and monochromatic beam of intensely

focused light that can be directed at some surface.

According to calculations by Dr. Arthur L. Schawlow, one of the pioneers

in optical masers, the following light-pressure values were postulated: Working

with a ruby laser having a peak power of 500 million watts in a beam whose

cross-section is less than 1 cm2, and assuming that the beam intensity

is roughly 1 billion watts per cm2, the intensity of the corresponding

electric field would be about 1 million volts per centimeter in the unfocused

beam. Using a good convex lens with a focal length of 10 mm, the laser's light

could be directed to a small spot one thousandth of a centimeter in diameter.

Here, the beam intensity would be one million billion (1015) watts

per cm2, and the optical-frequency electric field would have a

magnitude of about 1 billion volts per centimeter. Under these conditions,

light pressure as a result of the focused laser beam would attain a magnitude

of 15 million pounds per square inch!

Unfortunately, the immediate effect of this immense force is that there

are severe disruptions in even transparent substances, since the optical-frequency

electric field is more than that binding the outer electrons in most atoms.

Consequently, a given material (including diamond) is either drilled through

or vaporized without providing the desired propulsion effect.

However, the magnitude of laser-generated light pressure is large enough

to have more than passing technological significance, and much thought is

being given to materials that are able to physically withstand and transfer

imparted momentum without - literally speaking - going to pieces. A semi-critical

nuclear mass might be able to do this, and we also have a byproduct in the

form of plasma-which is easier to work with.

Shock-Wave Investigations

Intense mechanical shock waves can be generated by focusing a laser beam

in free air or compressed gas, since a special product is generated at the

focus point. This product, called "plasma," can be regarded as a collection

of positively and negatively charged particles. Plasmas are everywhere in

the universe, forming intensely hot gas under high pressure in the sun and

the stars. Plasmas are present in the flames of burning fuel and in gas-discharge

devices such as neon signs. Research on plasmas, particularly on many gas

discharges, led to the discovery of the electron and to the elucidation of

atomic structure.

A basic experimental setup for investigating shock-wave-type laser engines

is shown in Fig. 3. An engine assembly, designed by the author during

1963-64, is shown in the photograph on page 30. The high-pressure laser engine

is dwarfed by a liquid-fuel rocket motor, shown here for comparison of size.

Strong blast waves and gaseous plasmas will occur in high-pressure gases

by focusing giant pulsed optical lasers with short-focal-length optics to

converge within the test volume. Using argon gas at an initial pressure of

100 atmospheres and a laser energy discharge of 1.0 joule (1 joule equals

1 watt-second of energy), pressures in excess of 8 X 108 newtons/m2

have been reported. These forces are equaled only by chemical explosions that

are similar to those obtained from rocket fuels confined to small volumes

of expansion. Here, as there, if the "exhaust" that is produced by the device

is propagated in a unidirectional manner, then effective propulsion will be

the result.

The working principles of the laser engine have been simplified in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The working principles of a laser engine

are illustrated here.

A typical Kerr cell assembled for operation is shown here.

Filled with nitrobenzene or similar liquids, cell is opaque to light unless

it is energized by high-voltage electric field.

Fig. 5. One proposed design employs battery of 20

lasers inside rotating cylinder, all firing into a common chamber.

Fig. 6. A proposed laser engine energized by the

sunlight.

The ruby-type pulse laser is equipped with a helical xenon lamp and is

pulse-switched by means of a "Q"-spoiling Kerr-cell shutter. This shutter,

a sample of which is in photo below, is based upon the principle that certain

liquids transmit light only when an electric field is applied to them. Thus,

after the laser has been "pumped" by its xenon lamp and is in a highly excited

state, light oscillations between the reflectors (or end mirrors) can occur

only after the intervening Kerr cell has been opened. At that instant, laser

action takes place and the coherent, monochromatic beam is emanated in the

form of a giant pulse of light. Other switching principles may also be used,

such as rotating mirrors and polarizers, which can be inserted between a ruby

laser's end reflectors. These choices vary considerably from one experimental

system to the next.

Referring back to Fig. 3, formation of the plasma is detected by a

Kerr-cell-operated camera using Polaroid film with an A.S.A. rating of 10,000.

The magnitude of pressures developed can be sensed by fairly traditional high-speed

transducers. When the shock wave is generated, the gas attains high temperatures,

is ionized, and exhibits the unique ability to absorb light. Aside from air,

gases such as helium, argon, nitrogen, and deuterium have been used. After

the laser has been activated and propagates its radiation into a test cell,

plasmas generated in an argon atmosphere reach a peak after approximately

125 nanoseconds. Extinction takes place shortly after about 850 nanoseconds

have elapsed.

In order to determine a point of maximum electric field beyond the focusing

convex lens, a small piece of aluminum foil may be placed at a given spot.

Then, by moving and tilting the foil during successive firings, a precise

target position can be found.

Shock-wave-type laser engines have much in common with detonation-based

force generators. High load factors can be achieved by pressurizing the plasma-forming

gas, sometimes up to 2000 psi. At standard pressure, and using air as the

working medium with a laser input energy of 3 joules, a shock-front velocity

of approximately 3 X 104 cm/sec can be obtained.

Practical Applications

Regarding practical applications, the problem remains of providing proper

exit systems and plasma-forming "combustion" chambers of small working size

and mechanical rigidity. To afford strong, rapid pulsing of the laser engine,

proposed designs include rotating laser batteries which, like a revolver's

cartridge drum, fire into a common chamber, as shown in Fig. 5. This

particular design allows the individual battery members sufficient time for

recycling and cooling.

In deep-space operation, it is desirable to operate vehicular propulsion

systems from natural rather than on-board power sources. The sun, above all,

should certainly be able to provide an adequate amount of power for this type

of operation.

Fig. 6 illustrates the author's concept of a laser engine powered

by sunlight. The light concentrators take the form of Fresnel reflectors focused

onto a "Q"-spoiled laser assembly. Auxiliary electronics, energized by solar

cells, effect switching and en-route steering of the chamber and nozzle structures.

A gas supply is required as well.

The laser's basic capability as a promising prime mover for spacecraft

has been recognized both here and abroad. Ideally, the ultimate engine will

be one that can lift a large vehicle off a planet's surface and supply continuous

deep-space propulsion for any given length of time. Today, it would be safe

to place our bets with the light-pressure engine. The shock-wave engine should

be regarded as an intermediate step since it is too similar to a rocket.

(Editor's Note: In addition to the references cited below, readers who

have access to early issues of this publication will find a basic article

on ionic and plasma engines in our April, 1962 issue (page 25) under the title

"Electric Engines for Outer Space" by Ken Gilmore.)

References

Ditchburn, R.W.: "Light," John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. Second

edition, 1963.

Friedrich, O.M., et al: "Investigation of Strong Blast Waves and the Dynamics

of Laser Induced Plasmas in High Pressure Gases," #67-969, AIAA Electric Propulsion

and Plasmadynamics Conference, Colorado Springs, 1967.

Rashad, A.R.M.: "Diagnostics of Medium and Dense Plasmas using Self-Focused

Laser Beams," #67-707, op cit.

Ambartsymyan, R.V., et al: "Heating of Matter by Focused Laser Radiation,"

Soviet Physics JETP 21, December, 1966.

David, C., et al: "Density and Temperature of a Laser Induced Plasma,"

IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics, QE-2, September, 1966.

Caruso, A., et al: "Ionization and Heating of Solid Material by Means of

a Laser Pulse," Il Nuovo Cimento, Serie X 45, October 11, 1966.

Lengyel, B.A.: "Lasers: Generation of Light by Stimulated Emission," John

Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1962.

Posted August 20, 2024

(updated from original

post on 5/19/2017)

|

By L. George Lawrence

By L. George Lawrence