|

December 1967 Electronics World

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

John R. Collins' 1967

Electronics World magazine article captures the essence of magnetic materials

leaping from incremental tweaks to revolutionary shifts, like grain-oriented steels

that aligned crystals to slash transformer losses and shrink massive power gear

for aviation and grids. Alnico alloys ditched bulky speakers for sleek permanent

magnets, while ferrites -- ceramic wonders --tamed high frequencies with non-conductive

ease, spawning compact motors, tools, and early computer memories. Superconductors,

then lab novelties generating intense fields with zero resistance, hinted at sci-fi

applications from particle physics to space. These innovations democratized strong

magnets, trimming weight and waste across electronics. Fast-forward to today, and they've

exploded: neodymium powerhouses fuel EVs and turbines with unmatched punch; nanocrystalline

cores devour losses in smart grids; high-temperature superconductors like YBCO deliver

routine 20+ tesla for MRIs and fusion dreams, proving Collins' "quantum jumps" birthed

today's magnetic backbone for clean energy and quantum tech.

Advances in Magnetic Materials

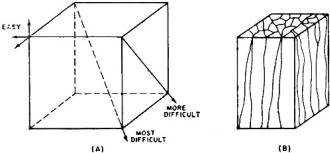

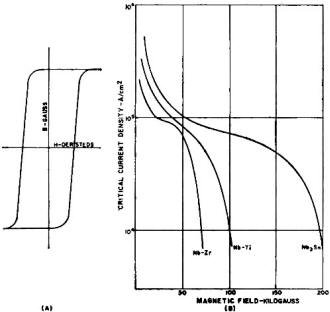

Fig. 1 - (A) A crystal of silicon steel, showing relative difficulty

of magnetizing along its various axes. (B) Grain structure of oriented Alnico magnetic

material is shown here.

By John R. Collins

Grain-oriented materials, new magnetic alloys, ceramic and ferrite magnets, and

superconducting cryogenic magnets are just some of the new developments advancing

magnetic technology.

Although much progress in magnetic materials can be ascribed to gradual refinements,

the more important advances have come from technological breakthroughs-quantum jumps

to new levels of capability. In the case of soft magnetic materials, the discovery

of grain orientation was perhaps the greatest accomplishment, contributing both

to economical power distribution and to important savings in size and weight for

airborne apparatus. For permanent magnets, a significant milestone was the introduction

of Alnico alloys which permitted, among other things, the manufacture of practical

PNI speakers to replace the cumbersome electro-magnetic speakers previously used.

Ceramics, or ferrites, have vastly influenced both hard and soft magnetic materials.

Their unusually high coercive force permits the design of relatively thin permanent

magnets as compared with competitive materials; their nonconductive properties,

coupled with high permeability, have revolutionized magnetics at radio and microwave

frequencies. In addition, they are comparatively easy to form in irregular shapes

and do not utilize critical materials.

Designing superconducting magnets for practical use has unquestionably been the

greatest accomplishment in recent years. Such magnets support magnetic fields far

stronger and more concentrated than any previously obtainable. They have added new

dimensions to old techniques and hold the promise of solutions to problems that

could not be tackled before because available magnetic fields were inadequate.

Grain-Oriented Steels

By far the greatest volume of magnetic material is used in the electric power

industry for the generation and distribution of electricity. To minimize I2R

losses, voltage is stepped up for transmission of power over distances and stepped

down to conventional levels before distribution to households. Large transformers

are most efficient for such purposes. Doubling transformer dimensions will increase

volume, weight, and losses by a factor of eight, but will increase power capacity

by a factor of about sixteen. Therefore, 250,000-kilowatt transformers weighing

more than ½ million pounds are not unusual.

Transformer power loss is measured in watts per pound. Although this loss may

be only a fraction of a watt per pound, the enormous amount of electrical power

consumed in the world today makes even minor improvements in efficiency important.

For many years transformers were made from hot-rolled iron sheet containing about

4 percent silicon to increase resistivity and thus reduce eddy currents. Typical

good grade material of this kind exhibits losses of about 0.5 watt per pound at

10 kilogauss and 60 Hz. Cold rolling makes a slight improvement in the material.

Grain-oriented steels first came into production after World War II. As shown

in Fig. 1A, crystals of silicon steel are magnetized most readily along their edges.

It follows that losses would be less if the crystals were aligned so that their

edges were oriented in the direction of magnetization. This is accomplished by means

of hot and cold rolling steps followed by recrystallization annealing. Individual

grains of the alloy are aligned by this procedure so that magnetization is easy

in the direction of rolling and losses are small, amounting to less than 0.3 watt

per pound at 10 kilogauss and 60 Hz. Coercive force may be as low as 0.1 oersted,

compared to 0.5 for ordinary silicon steel.

A further improvement in the past several years has produced magnetic steel oriented

in such a manner that it has two directions of easy magnetization -- in the direction

of rolling and perpendicular to it. These steels make it possible to operate a transformer

at 15 kilogauss instead of 10. Although losses rise to about 0.5 watt per pound

at the higher flux density, the accompanying reduction in the amount of material

needed more than compensates for the difference.

A parallel improvement has been an increase in maximum permeability -- through

refining the steel, removing impurities, and relieving strains -- from about 5000

in early transformers to about 35,000 today. This represents an important increase

in efficiency, since it permits transformers to be built with less material, and

losses are proportional to weight. Far greater permeability can be achieved through

further refinement, but the material is too delicate for use.

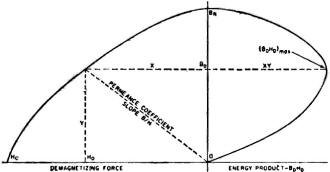

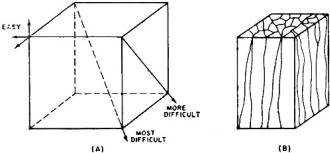

Fig. 2 - The demagnetization and energy product curve.

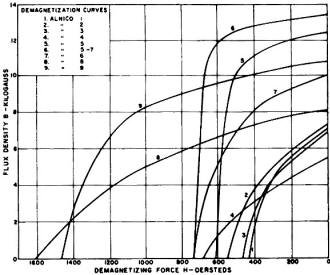

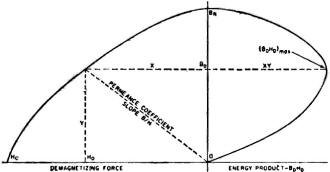

Fig. 3 - Comparative demagnetization curves for various Alnicos.

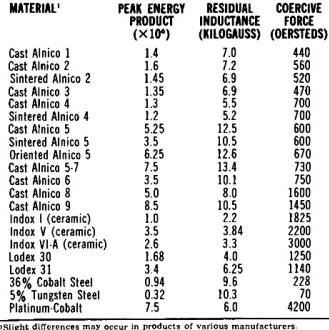

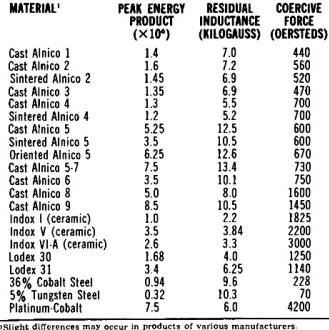

Table 1 - Characteristics of permanent magnet materials.

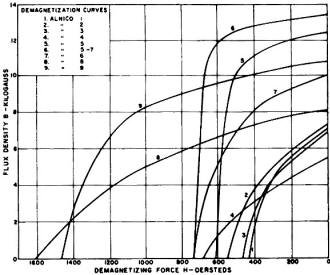

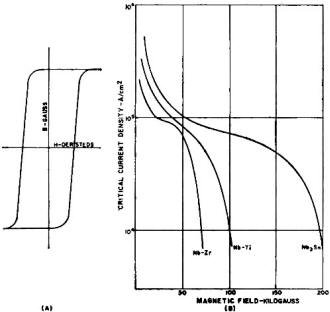

Fig. 4 - (A) Rectangular hysteresis loop characteristic of materials

used for magnetic amplifiers and memory cores. (B) Critical current density vs.

field for superconductors.

Permeability is also greatly enhanced through the use of nickel alloys. Permalloys,

embodying 78 percent nickel and 22 percent iron have been quite successful, and

alloys that include small quantities of chromium and molybdenum have been especially

efficient, since those elements increase resistivity. A notable example is Supermalloy,

which contains 70 percent nickel, 5 percent molybdenum, 15 percent iron, and 0.5

percent manganese, all of extremely high purity. When properly heat- treated, Supermalloy

has maximum permeability of about 1,000,000 together with coercive force as low

as 0.002 oersted. Alloys of this kind are useful for small transformers for communications

equipment and specialized applications, but are far too expensive for large power

types.

The Growing Alnico Family

A permanent magnet should have high residual induction to provide a strong magnetic

field and high coercive force to resist demagnetization. These properties may be

determined by plotting residual magnetism against the strength of the demagnetizing

force, as at the left in Fig. 2. The figure of merit of a permanent magnet is its

maximum energy product, measured in gauss-oersteds. This value may be determined

by multiplying x and y coordinates of each point on the demagnetization curve and

plotting the products as shown at the right of Fig. 2.

Early permanent magnets were made of hardened steel, usually with tungsten, chromium,

or cobalt added. All had maximum energy products of less than 1 million gauss-oersteds.

Carbon steel, for example, has a maximum energy product of 0.18; tungsten steel,

of 0.32; 33i percent chromium steel, of 0.29. By far the best material formerly

available was 36 percent cobalt steel, with a maximum energy product of 0.94.

Because of the relatively low magnetic fields that could be obtained with permanent

magnets, solenoid magnets were used almost exclusively for speakers in radio receivers

and amplifiers. With the discovery of the first aluminum-nickel-cobalt alloy in

1938, however, the situation changed rapidly and permanent magnets have found increasing

uses not only in speakers but in a multitude of other devices.

At the present time, there are nine such Alnico alloys in general use. The first

five have been in existence for a number of years, but the latter four are relatively

recent additions. There may be several variations of a single Alnico type, depending

on the method of construction. Alnico 5, for example, may have a maximum energy

product of 3.5, 5.5, or 6.25 million gauss-oersteds, depending on whether it is

formed by sintering, casting, or a special directional grain process.

In general, Alnicos are formed by conventional casting or powder metallurgical

techniques and a special heat treating procedure. The heat treatment consists of

heating the alloy to about 1300 °C and holding it at that temperature until a homogeneous

structure is achieved. This is followed by controlled cooling, then a period of

aging in which the alloy is heated to about 600 °C to increase coercive force and

energy product. Variations in the composition of the alloy or the time and temperature

of the heat treatment result in a variety of different magnetic properties. The

goal, of course, is to maximize the desired properties.

Alnicos 1 through 4 are isotropic, which means that they have the same magnetic

properties regardless of the direction of magnetization. Although they were considered

quite advanced when first discovered, they have only limited application today.

Anisotropic or directional magnets are made by applying a strong magnetic field

to the magnet during cooling. The field must also be in the same direction during

aging. Magnets having markedly superior properties are produced in this way.

More recently, Alnicos have been developed in which the crystal structure is

oriented in the direction of magnetic orientation. This is accomplished by casting

the molten metal against steel plates which chills the magnet and causes rapid cooling

and growth of long grains in the preferred direction. With careful regulation of

casting and heat treating, almost complete directional grain growth is achieved.

(Fig. 1B) . Alnico 5-7, a premium material for applications requiring superior performance,

is a product of this kind. Typical applications include airborne and space instrumentation,

where high magnetic fields are attained with magnets of reduced length and small

cross -section. The possible configurations of such magnets are limited, since the

direction of grain growth must correspond to the direction of the magnetic field,

and this can be done only in pieces magnetized in straight paths.

Alnico 8 is remarkable for its unusually high coercive force. This property makes

it especially valuable for circuits having large air gaps or involving large demagnetizing

influences. The most recent addition to the family is Alnico 9, whose energy product

is typically 8.5 but may be as high as 9.5 million gauss-oersteds in selected specimens,

and a coercive force of 1450 oersteds. It is a hard, brittle alloy that cannot be

machined easily except by grinding. Because orientation and magnetization must be

straight, the most common magnet shapes are cylinders and rectangles. Like Alnico

5-7, it is used in critical applications where a reduced size and weight without

sacrifice of energy is required. Comparative curves of these materials are shown

in Fig. 3.

Magnetic Particles

A limitation of Alnico magnets is the fact that the high-temperature heat-treating

processes that are involved make it difficult to hold close tolerances in physical

dimensions. The magnetic materials thus produced are hard and brittle, making grinding

difficult and expensive. This problem has been overcome in a family of magnets developed

by General Electric under the trade name Lodex. Lodex magnets grew out of the knowledge

that most permanent magnetic materials derive their magnetic properties from extremely

small and discrete particles dispersed in a non-magnetic medium.

In Alnicos and most other magnetic materials, the fine particles are precipitated

from the matrix as a result of high-temperature processing. In the manufacture of

Lodex, however, the magnetic elements are prepared by the electro-deposition of

iron-cobalt and are thermally treated to develop elongated shapes having superior

magnetic properties. These single-domain particles are then physically dispersed

in a non-magnetic matrix composed of lead and become the magnetic domains of this

synthetic system. In practice, the fine particle magnets and the lead binder are

mixed in powder form and then pressed into final shape. Properties can be regulated

by maintaining uniform proportions of magnetic particles to non-magnetic matrix,

and close tolerances can be obtained in the finished parts, since t pressing of

powders is the final operation.

Lodex magnets are less powerful than the best Alnico magnets, but they are available

with energy product as high as 3.4 million gauss-oersteds and coercive force of

1250 oersteds. The ease with which they can be handled permits wide latitude in

design and economies in manufacturing.

Fig. 5 - This superconducting magnet provides a field of 60 kilogauss.

Rare Earth and Hard Ceramic Magnets

Although still in the research stage, there are indications that compounds of

cobalt and rare earth elements, such as yttrium, cerium, praseodymium, and samarium,

may eventually yield permanent magnets with characteristics vastly superior to Alnico

alloys. Already experimental magnets have been produced of these materials which

exhibit energy product exceeding 5 million gauss-oersteds, and coercive force in

excess of 7000 oersteds. This is still a long way from the calculated theoretical

energy products, which range as high as 31 million gauss-oersteds, so there is much

room for development.

Rare earth mixtures are becoming commercially available at prices that compare

favorably with other premium magnetic materials. There is reason to believe that

fabrication will be easier than it now is with Alnico alloys.

Magnetic ceramics, or ferrites, are classified as "hard" if they exhibit high

energy product and high coercive force, and "soft" if they combine high permeability

with low loss in an a.c. field. The principal hard ceramic material is barium ferrite

BaO•6Fe4O2. Crystals of the material have a hexagonal

structure. The ferrite has a high degree of anisotropy and, therefore, a preferred

direction of magnetization.

The basic ingredients are barium carbonate and iron oxide, both readily available,

which are processed to obtain the desired characteristics. The resulting powder

is formed under high pressure in the required shape in a die. This fragile compact

is then sintered in a furnace at a high temperature. The magnet thus obtained can

be finished by grinding if necessary but is extremely difficult to drill or machine.

Barium ferrites, some of which are produced by Indiana General Corporation under

the trade name Indox, have the highest coercive force of any commercially available

magnetic material, being exceeded only by platinum-cobalt (see Table 1) which is

too costly for ordinary use. This characteristic makes it practical to use much

shorter magnet lengths than is possible with other materials. Like other ceramics,

barium ferrites have high electrical resistivity and are classed as non-conductors.

This permits them to be used in places where other magnetic materials would create

an undesired path for current or a short circuit. In addition, eddy current losses

and associated heating effects are extremely low when barium ferrites are exposed

to high-frequency alternating fields.

Because of their unusually high coercive force, barium ferrite magnets cannot

be demagnetized with ordinary demagnetizing coils, since these are not sufficiently

strong to overcome their field. For this reason, demagnetization is accomplished

when necessary by heating the ferrite above its Curie temperature (about 450 °C)

and cooling it slowly to avoid damage from thermal shock.

The first barium ferrites were non-oriented types, consisting of aggregates of

hexagonal crystals randomly arranged. Indox I is an example. It has a reasonably

high energy product and coercive force that compares favorably with Alnicos. It

is relatively inexpensive and thus finds extensive use. The characteristics can

be remarkably improved, however, through partial orientation (as in the case of

Indox II) or complete orientation (as in the case of Indox V and Indox VI-A). Orientation

is accomplished by subjecting the magnet to a very strong magnetic field during

the pressing operation and prior to final sintering.

Barium ferrite magnets are found in many common articles, such as cabinet latches,

can openers, and door closers. Because of their extremely high coercive force they

are especially useful in providing magnetic fields for motors and generators. In

hand tools, such as electric drills, they permit smaller and lighter devices than

is possible with conventional field coils. Their resistance to high-frequency field

makes them excellent choices for focusing applications, such as the periodic focusing

of traveling-wave tubes. They are also finding wide use in PM speakers, especially

for un- usually flat speaker designs which have been made possible through the use

of relatively short magnets.

Soft Ceramic Materials

Because of the high conductivity of metallic cores, losses mount rapidly with

frequency. For this reason, silicon steel is rarely used much above 400 Hz. Instead,

soft ceramic materials which have relatively high resistance are used as cores in

such devices as horizontal output transformers and deflection yokes for TV that

operate at about 16 kHz. They are also used for recording beads where, in addition

to their ability to handle high frequencies without significant loss, their mechanical

hardness provides superior resistance to wear.

The most common soft ferrites are composed of oxides of nickel and zinc. High

permeability material is made by sintering the oxides at high temperature until

a dense formation is obtained. For the higher frequencies, losses may be reduced

at the expense of permeability by increasing the ratio of nickel oxide to zinc oxide.

A superior soft material may be made from manganese oxide and zinc oxide, having

generally higher flux density, lower loss, and higher Curie temperature than the

nickel zinc types. The valence of manganese tends to vary, making manganese oxide

ferrites more difficult to produce. However, modern furnaces permit careful control

of firing conditions, so the problem is no longer as troublesome.

In recent years, ferrites have become important as cores for filter inductors,

i.f. transformers, antenna coils, and wide-band transformers where frequencies from

several hundred kHz to several hundred MHz may be encountered. The loss factor of

ferrites, discussed above, is too high for these applications and so a special series

of materials has been developed. These are characterized by unusually high resistance

and high "Q." "Q" refers to the efficiency of the material for converting from electrical

to magnetic energy and back again.

High-"Q" materials may be made from either oxides or nickel and zinc or oxides

of manganese and zinc. The manufacturing process is quite similar to that described

above except that the proportions of the compounds are not the same. In addition,

high-"Q" materials are somewhat under-fired, leaving them slightly porous. As a

result, their permeability is substantially less than ferrites intended high-frequency

use, but this factor is more than compensated by the reduction in losses at radio

frequency.

A class of ferrites known as garnets has been developed for use at microwave

frequencies. They have the general formula 3R2O3•5Fe2O3,

where R is any rare earth element. Yttrium iron garnet is an example of the type.

They have extremely high resistance and low loss. Typical applications include isolators,

phase shifters, and rotation devices. Placed within a cavity, such a ferrite causes

the plane of polarization of the microwave radiation to be rotated, thus permitting

nonreciprocal or one-way electrical networks to be constructed.

Square-loop ferrites are usually made by combining oxides of magnesium and manganese.

Other materials, such as nickel, copper, or calcium may be added to modify the properties.

These materials have high remanence, approximately equal to saturation flux density,

which gives the flatness at the top and bottom of their hysteresis loop ( Fig. 4A)

. Initial permeability is characteristically low, as is coercive force. Square-loop

ferrites are used for information storage and switching applications. One of their

primary uses is for core memories in computers. Switching speed is a very important

consideration, and this parameter has been reduced to a fraction of a microsecond

in some types.

Superconducting Magnets

Although superconductivity was discovered more than half a century ago, it has

been only in the past few years that the production of practical superconducting

magnets has become possible. The phenomenon was first noted in relation to mercury,

which was found to lose any measurable resistance at about 4°K. Early experimentation

demonstrated that tin and lead exhibit the same characteristic. As a result of concentrated

research the list has continued to grow. There are now 26 known superconducting

elements along with more than 1000 superconducting alloys and compounds.

The idea of winding magnet coils from superconducting materials is attractive

for obvious reasons. Since superconductors have no resistance they consume no power.

After a field has been established in such a coil, the terminals can be short-circuited

and the current will continue to flow indefinitely. In the absence of resistance

no heat is generated, and a much stronger field can be established in a small area

than is possible with conventional equipment. It is thus feasible, in theory, to

achieve extremely concentrated magnetic fields with lightweight apparatus.

Putting theory into practice was not easy. It was soon discovered that superconducting

elements lose all trace of superconductivity when the magnetic field exceeds a certain

critical value. This is attributed to the fact that the field is totally excluded

from the interior of the conductor at the lower flux levels, and that loss of superconductivity

occurs when the field penetrates the surface. Superconductors of this kind are called

"soft." They are unsuited for sustaining magnetic fields exceeding about 1000 gauss.

So-called "hard" superconductors are alloys and compounds that will continue

in the superconducting state despite partial penetration by the magnetic field.

Although they also lose superconductivity when field penetration is complete, many

of them are capable of sustaining quite concentrated fields before that transition

occurs. Theoretical calculations indicate that fields as high as 300 kilogauss may

be possible with hard superconductors, but this level has not yet been reached.

Superconducting alloys are usually quite ductile and easy to fabricate. The two

most promising at the present time are Nb-Zr, containing approximately 75% niobium

and 25% zirconium, and Nb-Ti, containing approximately 50% niobium and 50% titanium.

Both alloys are made from fine powders that are sintered to form wires. Nb-Zr has

a critical magnetic field of about 60 kilogauss; Nb-Ti of about 80 to 100 kilogauss

(Fig. 4B) .

Like most other superconducting compounds, niobium tin (Nb3Sn) is extremely brittle

and difficult to handle. However, it offers the greatest hope today of obtaining

superconducting magnets with fields in the vicinity of 200 kilogauss. Several methods

of forming niobium tin magnet coils have been devised. In one method, the tin is

deposited on niobium wire. After the coil is wound it is heat treated, causing the

tin to diffuse into the wire and react chemically to form niobium tin. A related

process involves placing powdered tin and niobium into a niobium tube which is heated

in order to form a compound after it has been coiled.

It is possible to wind a coil after the compound has been formed by coating a

thin metallic ribbon with a very thin layer of niobium tin. With proper care, a

ribbon of this kind cart be wound into a coil no more than an inch in diameter without

damaging the superconducting layer.

The highest magnetic field yet achieved with a superconducting magnet is about

140 kilogauss. This is still far short of the 250 kilogauss field that has been

obtained with a conventional magnet. However, conventional magnets in that range

required about 16 million watts to operate and huge quantities of water to dissipate

heat, whereas the superconducting magnets are relatively compact and require virtually

no power except the amount needed to refrigerate the superconducting coils.

A number of important uses are visualized for superconducting magnets. These

include such projects as improved bubble chambers for atomic research, deflection

systems for particle accelerators, plasma containment for thermonuclear reactions,

magnetohydrodynamic propulsion, and magnetic shielding and braking systems for space

vehicles.

Although most of these applications are in the future, it is important to note

that superconducting magnets are no longer laboratory curiosities but are becoming

standard equipment. As a case in point, consider the nuclear magnetic resonance

spectrometer manufactured by Varian Associates. This device requires a strong magnetic

field for its operation, and was traditionally supplied with a huge iron-core magnet

weighing 5000 pounds and capable of producing a 23-kilogauss field. Until quite

recently, such magnets represented the state of the art for NMR use: it was not

feasible to exceed that figure using conventional techniques. However, Varian now

offers superconducting magnets for use with its NMR spectrometers which weigh only

100 pounds and produce a field of 50 to 60 kilogauss ( Fig. 5).

Although it is necessary to refrigerate the coil with liquid helium, the dewar

holding the liquid and minimizing evaporation adds only 200 pounds to the weight,

so the total is still only a fraction of the weight of the conventional magnet.

Operating cost per kilogauss is less and there is better stability in the magnetic

field. Most important, however, is the fact that the markedly higher field has added

another dimension to NMR spectroscopy. The chemical shift of NMR spectra is proportional

to field strength, so results are clearer, more easily interpreted.

|