|

February 1967 Electronics World

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Operators didn't know how good

they had it in 1967. The story talks about the nuisance of having to sift through

"hundreds" of satellites, old rockets, and assorted space junk" in order to search

for and track potentially threatening objects in orbit around the Earth. We're into

the millions of objects in 2019, and the potential threats are infinitely larger.

The article mentions the use of an

AN/FPS-16 radar operating

in C-band to detect and measure the returns and then the results were analyzed in

an attempt to determine the character of the object. Open air test sites and anechoic

chambers were used to measure the radar cross section and characteristic signature

of many shapes to populate a database of recognizable returns that would help to

determine whether the space object was friend or foe.

Radar Signature Analysis

Typical of the radars used for signature analysis is this advanced

projects terminal measurements radar built by Raytheon for the White Sands Missile

Range in New Mexico.

By Edward A. Lacy

Every satellite and missile produces a distinctive pattern of radar echoes. These

can be employed to deduce satellite size, shape, as well as motion.

When our satellite-tracking radars detect a new foreign space vehicle, it surely

must cause some worrisome moments for our intelligence experts. For, after all,

such a satellite could be anything from a harmless scientific experiment to a surveillance

vehicle or, worse yet, a satellite equipped with a nuclear or biological warhead.

With hundreds of satellites, old rockets, and assorted space junk now in orbit

and with many of them passing over the continental United States, it has become

important to our military peace of mind to know the origin, capabilities, and intentions

of each of these objects. To determine this, the Air Force is building a surveillance

system to detect, track, identify, and catalogue all objects in space on their first

orbit.

Lest this sound like a simple matter, it should be noted that until recent years

it just was not possible for us to determine much, if anything, about such objects.

Of course, our radars told us the altitude, range, and velocity of a given satellite,

but even with the most precise radars it was not possible to "paint" a picture of

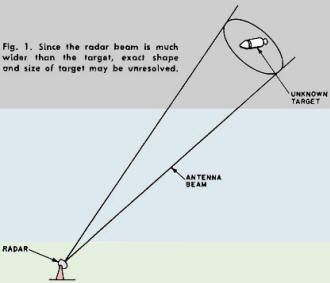

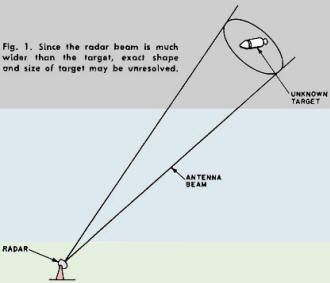

the satellite, that is, resolve the target in angle. As shown in Fig. 1, a

radar's beam is ordinarily too wide to give any indication of the shape of a satellite

which is an important factor in determining its mission or intent. At a distance

of 100 nautical miles from the antenna, for instance, a radar beam may be a mile

or more wide. To use such a beam to paint a silhouette of an object only a few feet

in diameter is like trying to fill in a "paint by number" drawing with a 6-inch

brush.

Fig. 1 - Since the radar beam is much wider than the target,

exact shape and size of target may be unresolved.

Over-all view of the control house at the Air Force radar target

scalier site (Rat Scat). The two antennas at the right are 10-ft dishes, while two

at the left are 6-ft dishes. These antennas are elevated on individual tracks when

they are being used for radar target measurements.

Fig. 2 - A compound body along with its radar signature.

The target end of Bunker-Ramo Corp.'s microwave anechoic chamber.

Foam plastic pyramids lining chamber absorb radiation.

Satellites such as Mariner IV have a more complicated radar signature

on account of the solar-cell paddles that are used.

Fig. 3 - Typical patterns produced by symmetrical bodies.

Fig. 4 - Patterns produced by rotating plate and cone.

While much of this information is still "classified" by the military, enough

has been released to indicate how a new technique, called "signature analysis" -

a remarkable bit of engineering detective work, is being used to determine satellite

size, shape, and motion.

Radar "Fingerprints"

Although the new system hasn't been refined to that extent as yet, it is almost

as if each satellite or reentry body has its own radar "fingerprint", which is a

plot of the signal strength of the radar echo (as recorded in the automatic gain

control circuit) versus time. In this technique, plots or signatures of the target

echo are broken down into patterns that represent the returns from objects of known

shape. These shapes are then put back together to define the complete shape of the

satellite - whether it is a cone, cylinder, sphere, or some combination of these

shapes (Fig. 2). Using other techniques of signature analysis, it is then possible

to determine the size of the satellite, its orientation if it is not tumbling, and

its tumble rate if it is tumbling.

Knowing these characteristics of the satellite, the analyst may then be able

to determine the satellite's intended mission. For example, if the satellite is

always oriented toward the earth as it passes over us, then it could very possibly

be a surveillance satellite. Particular shapes are optimum for certain types of

sensors used on surveillance satellites. On the other hand, extreme altitudes would

indicate that the satellite probably is not spying on us. By using this information

and making deductions, we can obtain a pretty good description of the craft.

Although plots of aircraft radar echoes have been available for several years,

it should be noted that signature analysis really began only in 1958. In that year

D. Barton of RCA was able to deduce the contours of Sputnik 2 from the plots of

echoes received on an AN/FPS-16 radar. By this process it was shown that complex

patterns of radar returns could be resolved into combinations of returns representing

simpler shapes and then put back together to indicate the original shape. In the

RCA publication, "An Introduction to Target Recognition", from which much of the

information in this article was derived, Charles Brindley reveals many of the techniques

used in signature analysis.

Cross-section Measurements

Signature analysis is based on radar cross-section: predicting it, measuring

it, recording it, and recognizing it. Radar cross-section is simply the size of

an object as it appears to a radar, irrespective of its actual size. While there

is no simple relationship between radar cross-section and actual size, generally

the larger the object, the greater its radar cross-section or reflectivity.

Obviously, the greater an object's cross-section, the easier it will be for the

radar to see it. Conversely, the smaller the cross-section, the harder it is for

the radar to acquire. The enemy takes advantage of this by shaping reentry bodies

so as to reduce their radar cross-section and by coating the vehicles with a radar-absorbing

material. Radar cross-section depends on radar frequency, the angle at which the

beam strikes the target, and the polarization of the signal.

To obtain laboratory cross-section data of actual satellites and other objects

is a difficult matter: it is hard to maneuver the satellite into known aspects,

satellites are expensive, and it is hard to repeat measurements. These difficulties

have lead to the development of test ranges, both indoors and out, for plotting

the cross-sections of various objects at rest.

In the indoor test range, called radar or microwave anechoic chambers, scale

models of various shapes and sizes are observed with radars which are scaled down

in size and up in frequency. Special radar absorbing materials are placed on the

walls of the chamber to prevent unwanted reflections. The scale-model test object

is placed on a turntable so that various aspect (viewing) angles may be obtained.

The radar signal is bounced off the object and the signal strength of the echo is

recorded on a strip-chart.

Anechoic chambers have the advantage of being immune to bad weather: you can

use them when it is raining, something you can't do with outdoor ranges since the

rain absorbs too much of the signal at the frequencies used on the model ranges.

Such chambers, though, can be an expensive proposition when waveguides and models

are built to small scale.

With outdoor test ranges the models do not have to be nearly as small. Avco has

a test range where 2500-pound models can be suspended up to 300 feet in the air.

At the radar target scatter site (called "Rat Scat") near Holloman Air Force Base,

New Mexico, static cross-section measurements can be made on objects weighing up

to 8000 pounds at frequencies from 100 to 12,000 MHz. On outdoor ranges such as

these, special care must be taken to eliminate or discount the return from the tower

or other supporting structures on which the target is placed since the tower may

have a greater cross-section than the target.

Various Types of Signatures

Now let us consider the various types of signatures or returns which we obtain

for bodies of various shapes, based on test range measurements. Figs. 3 and 4 show

the returns for a sphere, cone, cylinder, and other shapes. The returns shown are

for rotating bodies at a fixed position: the lobes may vary in width and number

for moving bodies.

Since a sphere looks like a sphere no matter how you view it, its radar cross-section

will be a constant level with no variation because of different aspect angles. The

cone and cylinder have more complicated returns because the strength of the echo

will depend on the angle or aspect at which the beam strikes the object. By the

use of certain approximations, most symmetrical bodies can be considered to be made

up of combinations of these basic shapes. If the satellite is not symmetrical (for

example, if it has solar cells mounted on paddles), the analysis problem becomes

more difficult.

In either a test range radar or an operational radar, the target signature may

be obtained from the automatic gain control circuit or the video circuits of the

radar receiver. The recording of the a.g.c. voltage versus time is usually made

with an analog strip-chart recorder. While this technique gives a good indication

of the average strength of the return signal, it is being replaced at many stations

by a video tape recorder which furnishes much more information since it records

on a pulse-by-pulse basis.

Using the recording of an operational radar and knowing the characteristic returns

of certain bodies obtained with a test range radar, the signature analyst can be

expected to come up with a reasonable approximation of the unknown body, provided

that both radars were looking at the target at the same angle.

Now that we've established the shape of the satellite, let's consider its motion.

While the more sophisticated satellites will be stabilized, it is possible for the

satellite to be tumbling which would indicate either a failure of the satellite

to perform as programmed or a lack of engineering ability on the part of the designers

and builders. In either case, it is important to know if the satellite is tumbling

and, if it is, the tumble rate. This can be determined by observing periodic repetitions

of the same cross-section pattern.

Thus far we have considered the cross-section just as a pattern and have ignored

units of measurement. To use cross-section to determine actual size of a satellite,

it is necessary to calibrate the radar, One method that has been used is to track

a 6-inch sphere suspended below a balloon and then calibrate the relationship of

the radar cross-section and the radar return accordingly.

By using appropriate formulas and by counting the number of lobes in one period,

one can find the length and radius of the object.

Reentry Body Study

Besides satellite target recognition, signature analysis is being used to study

reentry bodies. When a reentry vehicle enters the atmosphere, the shock waves formed

by the vehicle cause a plasma sheath - a concentrated layer of electrons-to be formed

on the vehicle. The plasma sheath has a drastic effect on the cross-section - the

reentry vehicle may show a significant increase or decrease in cross-section compared

to its cross-section as measured in free space. The ionized field - called the "wake"

- which trails behind the vehicle will show similar effects. Using signature analysis,

we can then determine how the vehicle is being affected by reentry.

In the military area, anti-radar signature devices (decoys) use built-in electronics

to reshape the returning radar echoes so that a small, inexpensive decoy can "look"

like a larger reentering vehicle.

A more important use of signature analysis is to be able to determine which reentry

bodies are enemy war-heads and which are merely decoys in the mass of reentry bodies.

Since the warhead must be identified in time for us to take defensive action, a

computer is necessary. A computer, however, tends to take things too literally:

if a return differs only slightly from the description which was given to it, the

computer will not recognize the object. But with new computers which are capable

of learning and with improved optical techniques for pattern recognition, perhaps

this problem is closer to solution.

|