|

November 1969 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

I have always found it

annoying when an author uses a symbol or subscript in an article without explaining

or somehow making obvious what it is. In this "Resistivity: Some Definitions" piece

from a 1969 issue of Electronics World magazine, the author's stated purpose

is to define terms related to resistivity, which he does well, but there are a couple

instances where subscripts for resistivity, rho (ρ),

are left for the reader to figure out. ρsp,

ρs, and ρv

have been replaced with ρspecific,

ρsheet, and ρvolume

, respectively, where needed. Sure, a careful reading of the surrounding content

clarified the intent, but you are not supposed to work that hard. Otherwise, this

is a great primer on the meaning of resistivity, how it is measured, and how it

is used to calculate the resistance of a device. Caution is advised in noting

and staying consistent with stated resistivity units when performing calculations.

Resistivity: Some Definitions

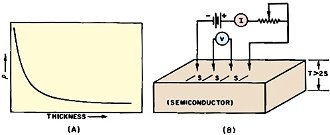

Fig. 1 - (A) In thin films, resistivity varies logarithmically.

Four-point probe (B) is used to measure crystal resistivity.

By Joseph Tusinski

Chief Technical Instructor, Old Dominion College

Often when defining technical terms or using them in an equation, many technical

men confuse them and unknowingly employ wrong expression.

Engineers as well as technicians some time have difficulty defining resistivity.

Resistivity and resistance are both related to the ability of a substance to impede

the drift of electronic charges. However, in specifically defining one or the other,

dimensions used in formulating each term are either disregarded or not even considered.

Resistance has dimensions of mass, length, time, and charge. Hence it is defined

in terms of volts per ampere. The unit of resistance is the ohm and its symbol is

capital omega (Ω). For example, when 100 Ω is expressed, what is implied

is 100 volts per ampere. Resistivity, on the other hand, is given in terms of resistance

per volume and its symbol is rho (ρ). Thus a problem

normally involves resistivity when it appears in a formula and the wrong dimensions

are used, or it would be more appropriate to say not used. Care should be exercised

in using tables of resistivities because, in many cases, identical substances may

have different numerical values of resistivity.

Resistivity appears subscripted in a number of ways. Some are:

ρspecific,

ρvolume,

ρrelative,

ρsurface,

ρsquare,

ρbulk,

ρsheet,

ρlattice,

and ρimperfection

Lattice and imperfection resistivity deal with lattice vibrations and imperfections

of a crystallographic structure. Hence technicians familiar with how semiconductors

and thin-films are made will encounter these terms as well as sheet resistivity.

Sheet resistivity may be encountered in a number of fields such as thin-film technology

or microwaves.

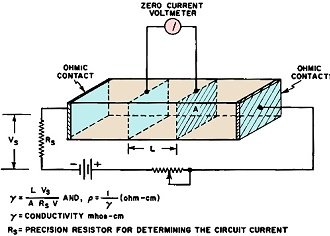

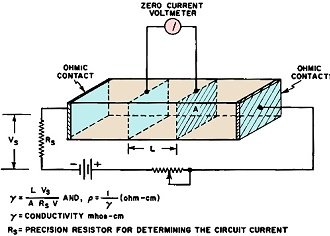

Fig. 2 - To measure bulk resistivity, current must be forced

through the material and the resulting voltage drop measured.

It should be mentioned here that all discussion about resistivity in this article

refers to a homogeneous material. A heterogeneous material may be physically attainable

or it may be obtained by virtue of frequency effects, such as skin-effect (see the

author's article "What is Skin Effect?," June 1963 issue of this magazine).

Fig. 1A shows that for very thin films, resistivity varies logarithmically and

that for thicker materials, the resistivity curve flattens out. A four-point probe

method (Fig. 1B) is used to measure sheet resistivity of semiconductor crystals.

If the thickness of the crystal is more than twice the probe spacing, the resistivity

of the material can be expressed by the equation:

ρsheet

= (2π Vs)/l

where s = probe spacing, V = voltage measured with a zero-current voltmeter, l =

constant current source, and 2π = 6.2832.

Bulk resistivity,

ρ∞,

is another term used to describe the resistivity or the impurity concentration of

a semiconductor. Ordinarily, when the resistivity of a material is measured, a known

current is forced through the material and the resulting voltage drop is measured.

Thus by Ohm's Law (R = E/I) the resistance is determined and related to resistivity

in ohms/cm3. Very often the term is shortened to ohm-cm, the cube being

implied. However, in bulk resistivity measurements, the resistance of the ohmic

contacts must not be included in calculations. Thus a method somewhat similar to

the four-point probe method is used (Fig. 2).

Square resistivity is perhaps the most misunderstood of all. Technicians usually

ask, "Square what?" or they assume that a square centimeter is implied. The implication

of square resistivity is that the length of the sample is equal to the width, i.e.,

is square. Resistivities are given in ohms/square. For example, assume a sample

of material having a resistivity of R ohms/square. Thus if four of the basic units

are combined, the length doubles, hence the resistance doubles (2R); however, the

width also doubles, which is the same as paralleling two resistors having values

of 2R each. The total resistance of the combination is: 2R x 2R / (2R + 2R) = R.

A simile can be derived by increasing the length three times and the width three

times, i.e., square. The total resistance is: 1/(1/3R + 1/3R + 1/3R) = R.

For example, suppose it is desired to achieve a resistance of 15 kΩ

with a material having a resistivity of 300Ω/square. Let us assume that the resistor

must have a minimum width of 20 mils: determine the length of the resistor. From

R = ρsquare

(L/W), L = WR/ρsquare

then L = (0.02 x 15,000)/300, or 1 inch. This equation states that to determine

the resistance of a specimen, the square resistivity is multiplied by the ratio

of the length to the width.

The use of specific, volume, and relative resistivities is normally relegated

to metals. These are perhaps the most popular tables of resistivity available, and

yet erroneous conclusions arise from their use.

In electronics, copper wire has been the most popular material used to interconnect

components. For this reason, many tables list the various characteristics of copper.

However, the characteristics of copper may be altered by various means (alloying

or annealing). Therefore a certain type of copper is used as a standard in evaluating

the conductivities of materials (γ = 1/ρ).

The standard, which represents 100 percent conductance, is annealed copper at

a temperature of 20° C. The resistance of a one-meter-long section having a uniform

cross-section of 1 mm is equal to 0.01724 ohm. Other methods were tried dealing

with the weight of copper; however these were not too fruitful, and the measurement

of length and area became the popular way to standardize.

The conductivity of aluminum may vary by as much as 35 percent depending upon

its composition. Pure aluminum (99.97 percent) has a conductivity of 64.6 percent

of standard copper. Thus if standard copper is considered to be unity, aluminum

has a relative resistivity of 1/0.646 = 1.54 or a specific resistance 1.54 times

that of standard copper. Thus values derived from a table consisting of relative

resistivities must be multiplied by the resistivity of copper to determine their

actual or specific resistance.

Tables relating the resistivity of a round copper wire were quickly formulated

so that most of the arithmetic could be simplified. From these, a table of specific

resistivities evolved. The popular dimensions chosen were the one -nail diameter

and one-foot length (the mil-inch was adopted in England). Thus they yield the specific

resistance of a material one-mil by one-foot, normally classified as Ω/mil-foot.

For example, annealed copper would have a specific resistivity of 10.36Ω/mil-foot.

Volume resistivities relate the resistance of a cubic structure. They are specified

as follows: 1. Ω/cm-cube (preferred), 2. Ω-cm, and 3. microhm-centimeters.

All three designations refer to a cubic specimen having square faces of one centimeter.

The resistance is to be measured between flat plates making contact with opposing

faces. Standard copper has a volume resistivity of 1.7241 X 10-6Ω/cm-cube

or 1.7241 microhm-cm. When

ρspecific,

and ρvolume

of copper are compared (1.7241 microhm-cm compared to 10.36Ω/mil-foot) and dimensions

disregarded, serious mathematical errors result. A simple example will help to illustrate

this point. The resistance of any uniform homogeneous material is given as R =

ρL/A (ohms).

It is obvious that if

ρ = 1.64,

or ρ =2.83

x 10-6, or

ρ = 16.9

is used in the equation, different results would be obtained. However, all of these

resistivities (relative, volume, and specific) are given for the same material.

Thus in order for the calculated resistance to be meaningful, the units of L and

A must be converted to correspond to the method used in determining the resistivity

of the material.

Another factor should be mentioned about determining resistivities of insulators.

For example, the surface resistivity of an insulator is measured from the opposite

edges of a square specimen. The bulk resistance of the body, which is parallel to

the surface, must be many times greater than the surface resistance. The volume

resistivity of an insulator must be determined using sophisticated guarding procedures,

so that surface charges will not mask uniform conduction through the sample. All

of the resistivities discussed are by no means all of the various forms of resistivity

that the technician or engineer will encounter. The intent is to bring about a respect

for a numerical value of resistivity and to be concise in specifying the dimensions,

method used, or theory involved in determining a value of rho.

|