|

July 1959 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Nothing has change in the

design and application of resistive attenuator pads since this article appeared

in a 1959 issue of Electronics World magazine. It could be legitimately reproduced

verbatim in the August 2018 issue of any magazine. When you crank through the equations

you will arrive at resistor values slightly different from those presented here

because the author chose the nearest standard 5% tolerance resistor values. For instance the 10 dB,

T-type attenuator for 75 Ω terminations shown in Figure 7 gives series branch

resistors of 33 Ω and a parallel branch resistor value of 51 Ω. The result

is an attenuator that does not present exactly the desired input and output impedances

or the exact attenuation value. More precise values are 39.0 Ω and 52.7 Ω,

respectively, so I am not sure why the author chose to use a 33 Ω resistor

rather than the 39 Ω (or even 36 Ω) standard value. 51 Ω is the closest

standard 5% resistor value. 1% tolerance resistors are as common today as 5% were

in 1959, so your attenuator / matching pad will end up closer to the ideal value.

I have fairly comprehensive coverage of

resistive attenuators

on RF Cafe with equations for both balanced and unbalanced "pi" and "T" pads for

both equal and unequal terminations.

Here is an article on

resistive pads from a 1966 issue of Electronics World.

The "Ins" and "Outs" of Resistor Pads

By Bob Eldridge

Fig. 1 - Matching "L" pads with formulas used for obtaining

resistances.

These ever-present matching and attenuating networks are often taken too much

for granted in service and other electronic work.

A pad is a network of resistors. It's as simple as that. The neat little device

at the end of the output cable of your signal generator or other item of test equipment

is quite likely to be a pad, perhaps with the addition of a coupling capacitor.

Little information on these devices appears nowadays, perhaps because they are

taken for granted. As a result, this means that a number of people do not know as

much about pads as they should. Learning the why's and wherefore's of these handy

devices not only enables the technician to service and work with his own equipment

in which they are used, but also to make up useful pads for many special purposes.

There are two main uses for resistive pads. They can be used to cut down a signal

that is too strong for the circuit to which it will be applied (attenuator pads)

or for the purpose of connecting together two circuits that present different impedances

to each other (matching pads). Sometimes, both uses are desired at the same time.

Where a pad is used to provide impedance match, there is always some incidental

loss of power, with the extent of this loss increasing as the difference between

the two impedances to be matched increases. For this reason, some device other than

the pad will be used to obtain matching in situations where the loss cannot be tolerated.

Take the case where a 75-ohm transmission line must be matched to the 300-ohm input

of a TV receiver in a weak-signal location. Here some sort of matching transformer,

which is more efficient, will be used. Where available signal is more than adequate,

of course, the simpler and cheaper resistive network can do the job.

Fig. 2 - (A) "L" pad with loads to be matched. (B, C) What

each end of pad sees looking at opposite, loaded end.

The "L" Pad

The networks and formulas shown in Fig. 1, used primarily for impedance-matching

problems, are known in telephone work as "minimum-loss" pads, since they are used

to connect circuits of different impedances while introducing the least loss of

signal that can be achieved without transformers. As with most pads, we have two

versions: the unbalanced and balanced types. The former is used where one conductor

is grounded, as where coaxial cable is involved. The balanced type comes in where

both terminals of the circuit are equally disposed with respect to ground potential,

as is the case with the antenna inputs of most modern TV receivers, for example.

You will note that, in the balanced version of the "L" pad (Fig. 1B), the

series resistors have been designated as R2/2. This has been done to

emphasize the fact that they are equal in value and that each is just half of the

single series resistor used in the corresponding unbalanced pad. Thus the same set

of formulas can be used for working out problems involving either version of this

pad. The balanced version of the "L" pad is sometimes called a "U" pad.

With the four formulas shown, it is possible to determine the values of resistors

for transforming from any impedance to any other. The accompanying tables in Fig. 1

have been worked out to show actual examples when transforming from three different

commonly encountered impedances to the ever-present 300 ohms. Resistance values

given are of the nearest standard-value units, rather than of the exact values determined

by formula. To start with, one of the last two formulas shown would have to be used

to determine the value of either R1 or R2.

Looking into "L" Pads

Straight mathematical formulas are unwelcome to many technicians. It is perhaps

of greater meaning to study the "L" pad as a network of series and parallel paths

to see what happens to it. In Fig. 2A, we see a specific pad designed to match

150 ohms to 300 ohms. First we "look into" the pad from the 150-ohm side to take

note of what this source impedance "sees." As shown in Fig. 2B, it sees a 220-ohm

resistor in parallel with 520 ohms. The latter is made up of a 220-ohm resistor

plus the connected 300-ohm load in series with it. A quick calculation (or an ohmmeter

measurement, if you don't like math) shows that this network comes to 155 ohms connected

across the 150-ohm source. The insignificant discrepancy of 5 ohms is due to the

fact that we have used standard-value resistors instead of the theoretically calculated

values.

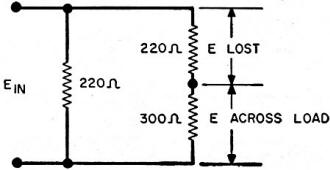

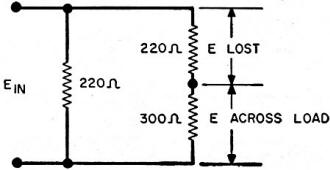

Fig. 3 - Although used for matching, the resistor pad must

introduce loss.

Fig. 4 - A pad can provide proper phono cartridge load with

an existing input.

Fig. 5 - The "T" pad provides specific attenuation without

an impedance change.

Fig. 6 - The "H" pad is the balanced version of the symmetrical

"T" pad.

Now we look into the pad from the other end, taking note of what the 300-ohm

end sees (Fig. 2C) with the 150-ohm source connected. First, there is the 150-ohm

source in parallel with a 220-ohm resistor. This comes to 89 ohms. In series with

this value is another 220 ohms, for a total value of 309 ohms-quite close to the

theoretically ideal 300 ohms.

In the manner shown, you can redraw any pad in terms of fairly simple series

and parallel networks. Always remember to include in the network the impedance of

the load at the end opposite from the one you are looking into.

As to the matter of efficiency, the "L" pad has been drawn in yet another way

in Fig. 3. While this resembles the version shown in Fig. 2B, voltage

distribution has been indicated to show why loss is inevitable. The load is part

of a voltage divider. Thus the resistor in series with it will always absorb some

part of the energy applied through the pad.

Note that, whatever the direction in which the transfer of energy through the

pad is to be, the lower impedance is always considered Z1 and the higher

Z2 for the purpose of the formula.

Some Uses of the "L" Pad

One of the most familiar applications of the "L" pad in TV service, already noted,

is as the terminating device for the output cable of a signal or sweep generator.

The coaxial output cable is usually matched to a 50- or 75-ohm output which, if

connected directly to the 300-ohm input of a TV set or FM tuner, can produce standing

waves often serious enough to distort the response curve so badly that alignment

is impossible. Simply gripping the output cable or changing its position under these

conditions can alter the shape and amplitude of response on the scope, or other

indicating instrument. The simple little device at the end of the cable is a matching

"L" pad that eliminates these problems.

Less obvious to the service technician, but also handy, is the use of an "L"

pad to match the output of a phonograph cartridge, such as some of the new ceramic

cartridges for which the manufacturer recommends a specific load impedance for optimum

response, to an existing circuit. In Fig. 4, a cartridge with a recommended

load of 110,000 ohms is to be connected to an amplifier stage whose input consists

of a 1-megohm volume control. With the two added resistors as shown, the cartridge

sees slightly over 110,000 ohms.

The pad is particularly useful in those cases where the output of a piezoelectric

cartridge is to be fed into a low-level preamplifier stage intended to accept the

output of a magnetic cartridge. To prevent overloading of the preamplifier, or of

succeeding stages, output of the higher-output pickup can be cut down to the proper

value by increasing the size of the resistor in series with the input of the preamp.

Symmetry vs Balance

All "L" pads are asymmetrical networks. That is to say, the input and output

impedances are not equal. There is some tendency to confuse the concept of symmetry

with that of balance. Symmetry pertains to impedances, whereas balance pertains

only to the relationship of the pad's terminals to ground. Thus, the pad shown in

Fig. 1B may be referred to as a balanced asymmetrical network.

"T" and "H" Pads

Table 1 - Factors for obtaining values for common loss figures

for any impedance.

Sometimes we have two circuits with matching impedances, but we wish to attenuate

the signal being transferred from one to the other without an impedance transformation.

Most commonly used for such a purpose is the "T" pad shown in Fig. 5. This

is an unbalanced, symmetrical network. When a balanced line is needed, another version

of this type of network, the "H" pad shown in Fig. 6, is used. This is a balanced,

symmetrical network. Because of the symmetry, we have only one impedance to deal

with here, and we call it the characteristic impedance, Z0.

To calculate the values of resistors for a pad of this type, we need only two

factors: the characteristic impedance already mentioned and the degree of attenuation

desired. In the formulas shown, the degree of attenuation is stated as the ratio

between the original voltage level and voltage level to which the original is to

be reduced. The formulas are the same for Figs. 5 and 6 except, of course, that

an adjustment has been made in the case of the balanced pad of Fig. 6 because

R1 will have to be split into two equal parts, one for each leg.

Fig. 7 shows some actual "T" pads that have been worked out for an unbalanced

line of 75 ohms impedance. Again, resistors chosen are to the nearest available

values, based on the formulas of Fig. 5. 20-db, 10-db, and 6-db pads are shown.

These provide, respectively, for voltage reductions of 10 times (that is, 1/10th

the original voltage), 3 times (1/3rd voltage), and 2 times (reduction to 1/2).

Using the formulas for Fig. 6, balanced "H" pads for similar voltage reductions

have been worked out for 300-ohm networks in Fig. 8.

The fact that attenuation is most often stated in terms of decibels, rather than

as a straight ratio between the original and reduced voltage, complicates the matter.

There is a formula for computing resistance values directly from db, but it's more

cumbersome than most technicians will wish to use. A table showing decibels with

corresponding voltage ratios may be used to convert for application of the relatively

simple formulas shown. In lieu of this, a table of factors for attenuator networks

may be used. Such a table, in abbreviated form, to show the factors for the most

commonly used degrees of attenuation (in db) is given here as Table 1.

Fig. 7 - "T" pads providing 3 steps of attenuation for fixed

75-ohm impedance.

Fig. 8 - "H" pads providing 3 steps of attenuation for fixed

300-ohm impedance.

Fig. 9 - How two attenuator pads (A) may be combined (B)

to provide more loss.

To use this table, simply determine how much attenuation in db is desired, and

what the impedance of the network is. The values of R1 and R2

are then determined by multiplying the factors listed in their respective columns

by the characteristic impedance. For example, suppose a 20-db pad is needed at 300

ohms impedance. R1 would then be 300 ohms multiplied by 0.8182, or 245

ohms. R2 is 300 ohms multiplied by 0.202, or 61 ohms. If an "H" pad is

involved, R1 is then broken into two equal resistors for either leg.

To the nearest available values, these calculations correspond with the 20-db pad

of Fig. 8, which was worked out from the formulas of Fig. 6.

In addition to these common attenuation steps, more complete tables of this kind

appear in many technical manuals. Increased attenuation may also be worked out from

Table 1.

If attenuation of more than 24 db is required, it becomes convenient to use two

or more pads in series. For example, 36 db of loss can be achieved by connecting

two 18-db pads in series, as shown in Fig. 9A. What makes this method particularly

convenient is that series-leg resistors can be combined. The pad in Fig. 9B,

for example, is electrically similar to that of Fig. 9A, with each pair of

series 120-ohm resistors combined into a single 270-ohm unit-the nearest standard

value.

Measuring Pad Impedance

Sometimes one is faced with the problem of having a "T" or "H" pad on hand but

not knowing what the characteristic impedance is. Two quick measurements and a calculation

will give the answer. Measurements are taken with an ohmmeter connected to one side

of the un terminated pad. The first measurement is taken with the far end of the

pad open. This impedance, Z0C is recorded. Then the far end of the pad

is shorted and this new reading, Zsc (impedance with shorted connection),

is recorded. These two readings, Z0C and Zsc, are multiplied together.

The square root of their product is the characteristic impedance of the pad; or,

EQUATION HERE. As a matter of interest, this is the same formula used to find the

characteristic impedance of a transmission line, readings being taken with an impedance

meter.

Uses for "T" and "H" Pads

In service work, symmetrical pads of this type are most often used for reducing

signal input to a TV receiver or amplifier, to prevent overloading and cross-modulation

effects. When a sensitive receiver is used in a location with one or more very strong

local stations and also some weaker distant ones, its a.g.c. system may not be able

to cope with the stronger signals. An attenuator pad in the lead of the antenna

for the local station (or a pad that can be switched in and out if there is just

one lead) brings the stronger signal down to a workable level.

In a service shop where only one channel is available to any practical extent

for checking out receivers, it is difficult to check on a.g.c. action or sync-circuit

operation, or to adjust the sound portions of TV sets with air signal. A series

of antenna pads can be very useful in simulating an adequate range of weak and strong

signals, with only one good one available. A switched set of pads could be made

up, but most often it will be found that two pads, say attenuating at 10 db and

20 db, each with antenna clips at one end and antenna terminals at the other, will

provide adequate variety.

Where signal is adequate, pads can be worked out for feeding two or more sets

on a single antenna with proper matching and adequate isolation from each other.

|