|

June 1968 Electronics World

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

I learned (or, "leared,"

in

MN Somali daycare lingo) a new word today - ergodic - from a 1968 issue of

Electronics World magazine. Ergodicity is a concept from mathematics and physics describing systems where

the time average of a property equals its average across all possible states (space

average). In simpler terms, a system is ergodic if, over time, it explores all possible

states in a way that reflects the overall statistical distribution of those states.

In physics and dynamical systems: An ergodic system eventually visits all parts

of its phase space uniformly. For example, in statistical mechanics, the ergodic

hypothesis suggests that a physical system will, over time, spend time in each state

proportional to its probability, allowing macroscopic properties (like temperature

or pressure) to be derived from time averages. In probability and stochastic processes:

A process is ergodic if its statistical properties (like mean or variance) can be

deduced from a single, sufficiently long sample path. For instance, a fair coin

flip sequence is ergodic because the long-term proportion of heads will converge

to 50%, matching the theoretical probability.

Electronic Measurements Using Statistical Techniques

Fig. 1 - Volts-time history of random data from four noise generators.

By Sidney L. Silver

Many physical phenomena produce nonperiodic, random signals that must be analyzed

by a statistical study of their average characteristics. Examples include thermal

and shot noise, static interference, irregular mechanical stresses, or vibration.

Techniques used are probability density, distribution correlation, spectral analysis.

In many branches of applied science and engineering, there occur problems involving

the measurement of physical quantities whose solution depends upon the proper interpretation

of the relative amplitude, phase, and frequency characteristics of complex waveforms.

Harmonic functions, for example, produce data which may be separated into simple

periodic waveshapes in order to determine the various frequency components and their

energy distribution. Such quantities are said to be "deterministic" since their

instantaneous values can easily be predicted as a function of time.

In practice, however, many physical phenomena produce non-periodic or random

information, which can best be defined in statistical terms. These quantities are

described as "probabilistic" since their instantaneous amplitudes cannot be predicted

with complete certainty at any future period of time. Instead, they must be analyzed

by making a statistical study of their average characteristics over a specific time

interval.

Typical examples of measurable quantities which produce random data are temperature

fluctuations in an industrial control process, noise and vibration from high-power

jet and rocket engines, buffeting forces on an aircraft at gust wind velocities,

acoustic pressures generated by turbulent air, notion of a structure caused by seismic

excitation, stresses of a stabilized ship exposed to rough ocean waves, static interference

in communications systems due to atmospheric disturbances, shot noise in a vacuum

tube, and thermal noise in a resistor.

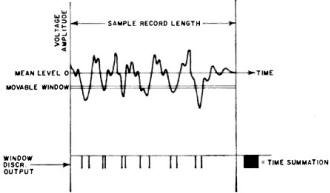

Fig. 2 - A graphic determination of probability density function.

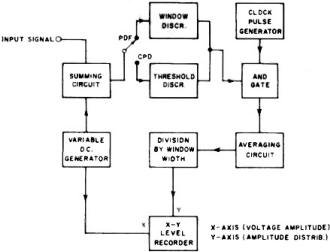

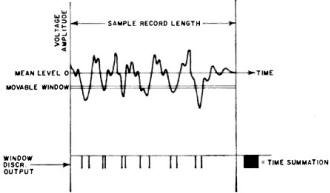

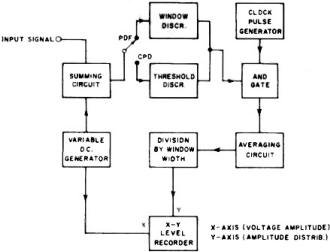

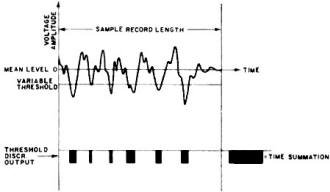

Fig. 3 - Amplitude distribution analyzer measures the probability

density and cumulative probability distribution.

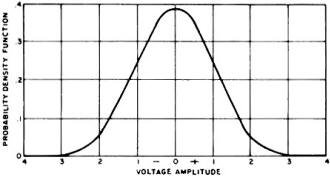

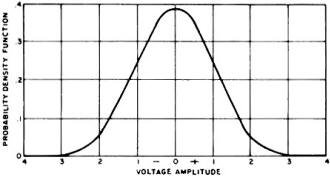

Fig. 4 - A normal probability density function curve.

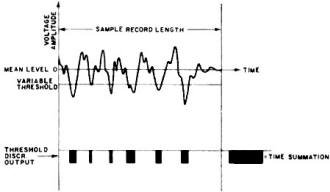

Fig. 5 - Evaluation of cumulative probability distribution.

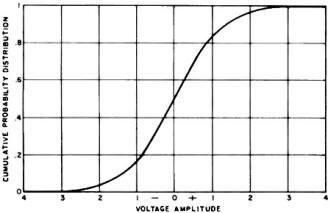

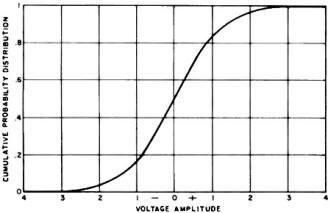

Fig. 6 - Cumulative probability distribution function curve.

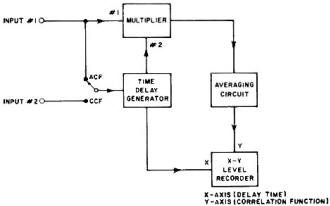

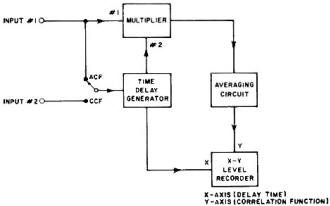

Fig. 7 - Correlation analyzer is used to measure autocorrelation

and the cross-correlation functions as described in text.

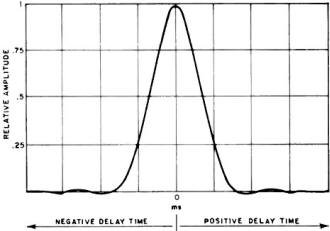

Fig. 8 - Autocorrelation function of wide -band random noise.

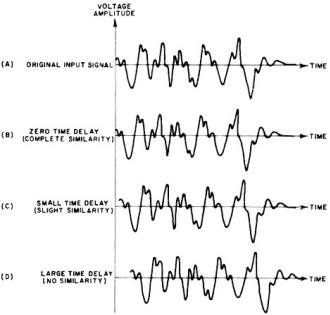

Fig. 9 - Time-shifting of the sample record during autocorrelation

scanning process to assess degree of similarity.

Fig. 10 - (A) Voltage-time plot of sine wave immersed in noise.

(B) Resulting autocorrelogram extracts the periodic component.

Fig. 11 - (A) Time plot of sawtooth wave in noise. (B) Time function

of reference pulses. (C) Cross-correlogram.

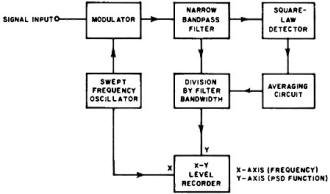

Fig. 12 - Functional diagram for power spectral density analyzer.

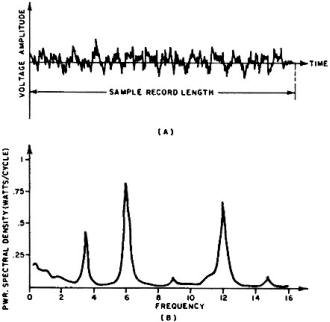

Fig. 13 - (A) Voltage-time plot of random variations. (B) Power

spectral density curve shows relative power distribution vs frequency.

Characteristics of Random\Waveforms

To demonstrate the nature of a random process, the voltage-time history of a

number of random -noise generators of identical design and construction is plotted

on a chart recorder (Fig. 1). For convenience, the mean value of each waveform is

arbitrarily chosen to be zero. By operating all generators simultaneously the collection,

or ensemble, of sample records is observed to fluctuate erratically, each waveform

representing only one of many possible occurrences. Clearly each observation of

the instantaneous magnitudes is a unique phenomenon, since the waveshapes never

exactly recur in a finite time period. Any attempt to make a precise, detailed analysis

of the fluctuations by observing previous values would be meaningless.

Theoretically a thoroughly accurate implementation of the random process would

involve an infinite number of sample records over an infinite time period. In practice,

however, only a finite number of noise generators need be considered, since the

long-term average characteristics of the amplitude values remain unchanged by any

additional noise sources. By applying statistical concepts to the measurement of

these random signals, it is possible to quantitatively describe them by computing

the integrated values of the waveforms over a predetermined interval of time. Some

of the apparent statistical variations can then be determined and a reasonably accurate

estimate of the future values easily obtained.

If the statistical properties of an ensemble (of sufficient length) do not vary

with time, the ensemble is said to be stationary. This implies that the mean value,

the amplitude distribution about the mean value, the number of peaks per unit time,

and the predominant frequencies, if any, of the collection of sample records is

the same. In this article, reference will be made only to those stationary random

phenomena with ergodic properties, i.e., where the time average of a single sample

record is equal to the corresponding ensemble average value, thus leading to the

same statistical results. Fortunately, most statistical phenomena are generally

ergodic so that such random data can be properly measured from a single sample record.

In the electronic measurement of random information, there are three domains

in which the statistical parameters may be processed: amplitude domain (probability

density and distribution), time domain (correlation), and frequency domain (spectral

analysis). Any of these can be implemented through analog or digital techniques.

Amplitude Domain Measurement

An important means of characterizing random data in the amplitude domain is the

probability density function (PDF), which describes the probability that the waveform

amplitude will assume a value within some specified range of values at any interval

of time.

Initially, the quantity to be analyzed is picked up by a suitable transducer

which converts the original signal into electrical form. The computation of the

PDF is most conveniently accomplished by recording a sample of the signal on a magnetic

tape loop. During the playback mode, the signal is continuously compared with a

reference level, or "window," discriminator which "slices" the sample record into

a very narrow amplitude range (Fig. 2), thus allowing only that portion of the signal

to pass through the system. The signal waveform is then integrated over the time

the signal spends within the amplitude window. At the end of each tape revolution,

the integrated signal is plotted and the window voltage is moved one incremental

step before the next integration cycle begins. This process continues until the

scanning band sweeps the entire amplitude range of the input signal, producing a

graphic representation of the amplitude distribution curve.

A functional block diagram of a typical amplitude distribution analyzer is shown

in Fig. 3. In the PDF mode of operation, the input signal is nixed with a variable

d.c. potential. This provides a bias voltage which allows different levels of the

waveform to be sampled by the window discriminator, and simultaneously shifts the

X-axis of the graphic recorder. Each time the instantaneous value of the signal

falls within the limits of the window, the and gate opens and passes 1 MHz clock

pulses to the averaging circuit. By this means, a measure of the total number of

pulses passed by the window circuit is obtained, expressed is a percentage of the

total number of pulses generated.

The time average may be obtained either by a true integrator (consisting of an

operational amplifier with feedback capacitor), or by a low-pass RC filter which

continuously smoothes the amplitude fluctuations. In general, true averaging is

employed when the scanning process is accomplished in discrete steps (stepped scan),

and RC averaging employed when a continuous scan sweeps the window. Finally, the

required division of the average sampling time by the window width (fixed amplitude

window voltage) yields the probability density function. Applying this parameter

to the Y-axis of the level recorder produces a plot of PDF vs. voltage amplitude.

Fig. 4 shows a normal, Or "Gaussian," PDF curve which is frequently encountered

in random data measurement. Here the higher portions of the symmetrical curve correspond

to the region where most of the input signal values occur, while the lower sections

indicate values which rarely occur. The area of the curve is based on a scale of

unity (or 100 %), so that any given area under the curve may be expressed in terms

of a percentage of all values represented by the entire cure. Thus, for example,

the probability that the instantaneous amplitude values of the input lie within

a range bounded by zero and +3 volts, is 50.

An alternate method of evaluating the amplitude distribution of a random waveform

is a measure of the "cumulative probability distribution" (CPD), which contains

the same information as the density function but presents it in a different form.

The value of the CPD function is defined as the probability that the input signal

is equal to, or below, a given amplitude.

In this mode of operation, one of the two thresholds of the window discriminator

shown in Fig. 3 is eliminated, thus extending the amplitude slice to include all

of the magnitudes that are less than, or equal to, the remaining threshold. Initially,

the reference level is set below the maximum negative value of the sample record

to be examined. As the threshold voltage sweeps upward from negative to positive

values (Fig. 5), an increasing portion of the input signal will lie below the reference

level. By com- paring the proportion of time that the signal falls below the threshold

to the total sampling time, a plot of the CPD function vs voltage amplitude is automatically

produced (Fig. 6). At the completion of the scanning process, the entire signal

waveform lies below the reference level and the integrated output is considered

to be 100%.

The principal applications for amplitude distribution measurements include the

determination of threshold levels in mechanical stress analysis, detection of non-linear

structural characteristics, surface and thickness instrumentation, and testing for

normality of random data.

The Domain Measurement

One of the most powerful techniques used to describe the properties of random

fluctuations in the time domain is the correlation function. The correlation concept

determines the extent to which a future value of a random quantity will be the same

as preset value of that quantity. By establishing a measure of similarity between

two waveforms, or by determining the influence of one signal upon another, a quantitative

analysis of the degree of randomness may be obtained.

An important parameter employed in the computation of random data is the "autocorrelation

function" (ACF) . This quantity refers to the dependency of a random signal upon

a time-shifted version of itself, and provides a convenient means of determining

the presence of a periodic signal obscured in a background of random noise. To implement

this process, it is necessary to delay the random signal by a variable time displacement,

multiply the signal value at any instant by the value preceding the delay time,

and finally average the instantaneous product value over the total time of the sample

record.

Fig. 7 shows a typical ACF analyzer which operates in conjunction with a special-purpose

instrumentation tape recorder. In this arrangement, a time sample of the signal

to be analyzed is recorded on a magnetic tape loop, and fed to a time-delay generator

to provide the necessary lag time. The variable time displacement is obtained by

means of a movable playback head which automatically advances one small step for

each revolution of the tape loop. Both the input and the output of the delay generator

are then multiplied and time-averaged so that at the end of each integration cycle,

the output appears as a series of discrete plots on the curve. hi some instruments,

correlation values are measured while the delay time is continuously varied through

the time displacement of interest, so that a continuous output curve is obtained.

The sample record is recirculated until the information at each time delay is completely

scanned and a graph of ACF vs time displacement is plotted on the X-Y recorder.

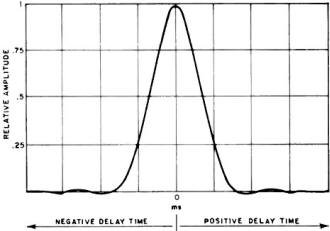

Fig. 8 shows an ACF plot, called an "autocorrelogram ", which is typical of wide-band

random noise. Assuming that the curve is plotted on positive and negative delay

values, the graph is observed to be a sharply peaked symmetrical pulse which reaches

a maximum value at zero time delay. The pulse then diminished to very low values

until the correlation function reaches zero at large time delays.

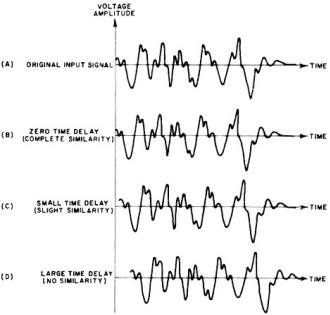

In order to interpret the form of the ACF curve, the relationship among the time-displaced

versions of the input waveform is given in Fig. 9. At zero delay time, the random

fluctuations applied to each input of the multiplier are in-phase. Since each positive

and negative ordinate in (A) is identical to its counterpart in (13), the product

of both values contributes a positive term to the sum. As the delay time increases

during the scanning process, the waveform becomes less and less related to itself

in (C), until the point is reached in (D) where the similarity is completely destroyed.

Now that each positive product value is offset by another negative product, the

sums rapidly decrease and the ACF reading falls effectively to zero.

If a sine wave were fed to the ACF analyzer, the autocorrelogram would also be

sinusoidal, having the same frequency and harmonic content as the input signal but

dropping all phase information. It is reasonable to expect, therefore, that an ACF

measurement of a wide-band noise record containing a hidden sine-wave component

(Fig. 10A) would have some of the characteristics of both the random noise and the

periodic signal. The resulting autocorrelogram in Fig. 10B indicates the peaked

curve at zero delay, with the sinusoidal component persisting over all time displacements.

Clearly the correlation technique makes it possible to detect and recover periodic

information by greatly improving the signal-to-noise ratio (as much as 40 dB) of

an incoming signal.

Now that the frequency of the periodic signal to be extracted from the random

noise is known, a more powerful technique, called the "cross -correlation function"

(CCF), may be applied. This is accomplished by switching the ACF analyzer, shown

in Fig. 7, to the CCF mode of operation. In this arrangement, the random signal

fed to the direct input of multiplier #1 is independent of an external periodic

waveform applied to the time-delay generator. Since the delayed input to the instrument

is now a pure sine wave of the same frequency as the hidden periodic signal, the

CCF analyzer produces a still greater improvement in signal-to-noise ratio and,

in the ideal case, reduces the noise components of the signal to zero. An important

advantage of this method over autocorrelation is that phase information is preserved,

so that the resultant cross-correlogram is a proportional reproduction of the original

time function.

Another method of detecting a signal masked by extraneous noise is indicated

in Fig. 11. This technique consists of cross-correlating the obscured signal (Fig.

11A) with a series of narrow pulses (Fig. 11B) which have the same fundamental frequency

as the obscured signal. The resultant CCF curve (Fig. 11C) reveals the hidden signal

to be a triangular wave.

The cross-correlation technique may be employed to establish a possible "cause

and effect" relationship between a disturbing sound source and a reverberant condition.

In acoustic vibration problems, for example, cross-correlation is useful in determining

the transmission paths and propagation velocities of a random vibration source.

By placing one microphone close to the source of the disturbance and moving another

microphone to different locations in sequence, a CCF computation is performanced

for each point. If multiple sound paths exist the cross-correlogram will contain

one peak for each sound path, while unrelated disturbances will rapidly correlate

to zero. The delay value at each peak corresponds to the transmit time of the transmission

path, and the ordinate of each peak indicates the relative contribution of each

sound source.

Frequency Domain Measurement

Since random waveforms are characterized by the relative distribution of their

frequency content, the analysis of non-periodic signals may be obtained in terms

of the "power spectral density" (PSD) function. This parameter describes the harmonic

composition of random data in terms of the mean square, or average power distribution

over the frequency spectrum. To make an analysis, it is necessary to filter the

input signal and average the squared instantaneous value over the total sampling

time.

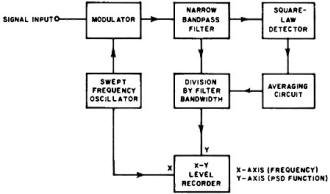

In the PSD analyzer shown in Fig. 12, the data stored on a magnetic tape loop

is heterodyned in the modulator by the output of a swept local oscillator. The modulator

output is then fed to a highly sensitive narrow bandpass filter (with a fixed center

frequency), which extracts that portion of the signal whose frequency range lies

within its passband. The frequency components are detected by the squaring circuit

and averaged by an RC filter whose time constant is set equal to the sample record

length. Where a true integrator is used for averaging, the transient produced by

the tape splice is used to derive a trigger pulse in order to reset the integrator

at the end of each tape loop period. The required division of the mean square value

of the averaging network by the filter bandwidth may be obtained by a proper scale

calibration. As the sweeping oscillator scans the frequency range of interest, the

center frequency of the bandpass filter is progressively moved, and output of the

analyzer is displayed as a continuous plot of PSD function vs. frequency.

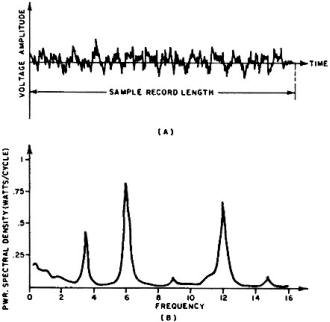

In Fig. 13A, a sample voltage-time history record is shown of an undesirable

random vibration, such as that produced by industrial machinery. By feeding this

data into the PSD analyzer, the resultant power spectral density curve (Fig. 13B)

shows how each peak level represents the signal contribution within the sample bandwidth.

Since the total power distribution is equal to the entire area under the curve,

the power in each of the peaks can be calculated from their individual areas. Now

that the hidden components in the frequency domain are easily identified, and knowing

the rotational speed of the machine parts, the disturbing vibration source can be

located and eliminated.

Where the phenomena being investigated involve the analysis of two related random

processes, some knowledge of the phase relationship between the two quantities is

sometimes required. For example it may be necessary to determine to what degree

an acoustic source of vibration is responsible for the mechanical vibration in a

metallic structure. This can be accomplished by means of a "cross-spectral density"

(CSD) analyzer which measures the linear relationship between the power spectral

density data represented by the two sample records.

The statistical concepts discussed have been restricted to the analog measurement

of stationary random data. Since the processing techniques do not, for the most

part, apply to the analysis of non-stationary random waveforms (whose statistical

properties change with time), more sophisticated methods must be developed to handle

such data.

|