|

March 1960 Electronics World

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Electronics World, published May 1959

- December 1971. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Perhaps one of the most frustrating

situations to find yourself in if you are a hard core audiophile is being an unmarried

enlisted man in the military, living in the barracks. Unlike residing in a college

dorm where comparatively there is no iron hand of peaceful existence enforcement

to quell a desire for music hall sound levels with bass saturation that can rock

you off your chair (other than dorm mates threatening to beat you to a pulp), in

a military establishment there is an immediate threat of arrest, rank demotion,

monetary fines, or a letter of reprimand (aka nonpunitive punishment) for blasting

a stereo (and your barrack mates might beat you to a pulp). One guy I shared a USAF

barracks room with had a couple thousand dollars worth of stereo equipment in a

19" rack in the room. It had something like a 1,000 watt quad speaker amplifier

(vacuum tubes for the output drivers of course - none of those emotionless transistors),

reel-to-reel tape deck, dual cassette tape deck, AM / FM / shortwave tuner, professional

quality turntable with a precision balanced tone arm and jeweled stylus, quad channel

equalizer, and other gizmos that I can't recall what they were. Oh, and of course

there were four monster speakers with finely tuned crossover networks for sub-bass,

bass, midrange, and tweeter speakers. On Saturday nights sometimes a pre-arranged

demonstration of the system's capability was given. Boston's "Don't Look Back"

would be played on the reel-to-reel and the volume cranked up (turntable couldn't

be used because the vibration would cause it to skip). After the bodies got up off

the room and hallway floors, congratulations and beers went 'round. Base security

probably thought an explosion had been detonated on the base.

See also "Room

Acoustics for Stereo" in the February 1960 issue of Electronics World.

More About Wide-Stage Stereo

By Paul W. Klipsch / Klipsch and Associates,

Inc. By Paul W. Klipsch / Klipsch and Associates,

Inc.

For stereo coverage of a wide listening area the addition of a center channel

speaker along with a pair of corner speaker systems is recommended.

Stereo enhances reproduced sound by supplying the sensations of depth, improved

definition, and enlargement of apparent volume of the listening room.

Defining "high-fidelity" as the accurate reproduction of original tonality has

its counterpart in stereo as the accurate reproduction of the geometry of the original

sound. The two should convey to the listener the mental picture of the original

sound, both in tonality and geometry. The essentials of stereo are:

1. Breadth or apparent width of the sound source.

2. Spatial continuity or a continuum of sound rather than several point sources.

3. Directionality or the ability of the observer to locate sounds across the

stage in approximately the locations as originally generated.

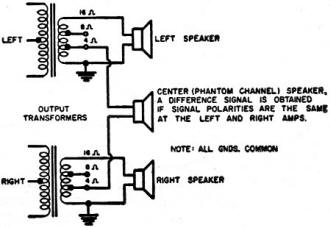

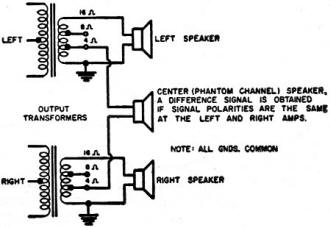

Fig. 1 - Arrangements used in experiments.

Steinberg and Snow1 showed that three sound channels were necessary

and sufficient to achieve a reasonable approach to these requirements. Experiments

by this writer confirm their conclusions, including the feasibility of deriving

three channels from two sound tracks.

Fig. 2 - (A) Actual locations of sound sources. (B) Apparent

locations with two speakers. (C) Apparent locations with center speaker added. (D)

Apparent locations during live listening experiment.

Fig. 3 - Bass response of speaker system.

Two-Speaker Stereo

The author's own early experiments in stereo led to the conclusion that if two

speakers were far enough apart to produce a satisfactory stage width, there was

a tendency toward a two-source effect.

In a 16 foot by 25 foot room, the various arrangements of speakers shown in Fig. 1

were tried. In Fig. 1A, the stereo effect was noted only at close proximity

to the array; in Figs. 1B and 1C, the listening distance was greater but the two-source

or "hole-in-the-middle" effect was objectionable. In Fig. 1D there was a lack

of stereo effect while in Fig. 1E, the stereo effect was evident, but the

dependence on wall reflections resulted in poor mid- and high-frequency response

and a hole-in-the-middle. In all cases, focus of a soloist was possible only for

one listener on the axis of symmetry.

Phantom Center Speaker

The derivation of a phantom center channel has been the subject of a number of

articles but seems to have been done first by Steinberg and Snow in 1933. The manner

of derivation has been discussed in various publications.2,3,4

Qualitatively, the derived third channel resulted in retention of the geometric

integrity of a string quartet and a large orchestra; a soloist standing some six

feet to the left of the podium was reproduced a little to the left of the center

speaker.

Quantitatively, a study was made of the geometry of reproduction.3

Sounds were generated in the pattern shown in Fig. 2A. With a two-speaker playback,

an observer plotted the apparent sound sources as shown in Fig. 2B. With the

three-channel playback using the derived center channel, a typical observation was

that of Fig. 2C. As a "control" the same observer listening to the original

sound (not over the loudspeakers) plotted the apparent sources as shown in Fig. 2D.

The sounds were generated by a person speaking at the indicated locations, outdoors,

and reproduced in a 16 foot by 25 foot room with speakers on the 25-foot wall. The

results in Fig. 2D were obtained with the observer wearing a hood so he could

see to plot his results but could not see the person speaking at the indicated locations.

Observers as much as 11 feet off-axis plotted results which were almost as accurate

as those shown. This corroborates the work of Steinberg and Snow, indicating only

small shifts of the virtual sources as the observer moves in front of a three-channel

array.

Fig. 4 - Increase in area of stereo effect.

Phantom-Channel Theory

The philosophy behind the phantom-channel technique may be stated as follows:

If two microphones are properly placed relative to each other and to the sound

source, their combined output is that of a single microphone in the middle; this

microphone "that wasn't there" can be reproduced by re-combination. The output of

an actual third microphone can also be recovered by re-combination.

In practice, this combination may be accomplished by simple addition. The theory

of the third channel derived from two sound tracks is still being developed, but

it appears that crosstalk is subordinate to signal mutuality. (Crosstalk is the

inadvertent transfer of signal from one channel to another; signal mutuality is

the natural consequence of one microphone in a stereo array picking up signals pertinent

to other microphones.7)

The fact that the center channel carries sound from the flanks as well is true

whether the channel is derived or independent. Experience shows that with proper

adjustment of levels, a high degree of accuracy of geometric reproduction may be

obtained with either the derived or independent center channel. As little as 2 db

can produce a shift in the virtual sound source.

Speaker Placement

In the experiments involved with Fig. 2, the flanking speakers were placed

in corners. This was deemed desirable for improved stereo geometry and also for

improved tonality. Referring again to Figs. 1A, 1B, and 1C, no sound appears to

come from outside the speaker array. Although the arrangement of Fig. 1E produced

a "wide-stage" effect, it could not fulfill the requirements either of good geometry

or good tonality. Thus, the arrangement of Fig. 1C plus a center channel was

regarded as the only feasible array.

Fig. 5 - Simple method of obtaining the phantom channel

after the power amplifiers. Speakers have 16-ohms impedance and equal efficiency.

Connection to 400hm tap results in half (3 db less) power to center speaker.

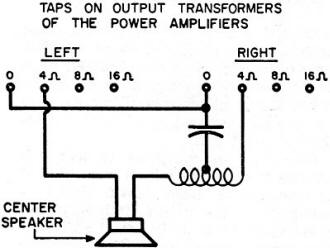

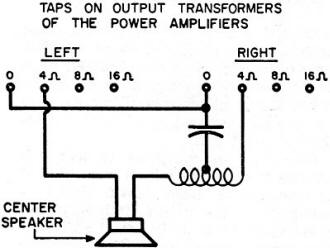

Fig. 6 - Deriving the center channel.

Fig. 7 - Method proposed of combining the same polarity

signals without cancellation.

Fig. 8 - This circuit may upset feedback ratio and cannot

be used in all amplifiers.

Fig. 9 - Another method proposed by the author to obtain

a sum and difference phantom-channel signal with 1:1 transformer.

Fig. 10 - Method of obtaining a sum signal from two power

amplifiers by first reversing phase of one of the input signals.

Monophonically the speaker response is improved by corner placement as a result

of: 1. Complete room coverage with 90-degree tweeter radiation angle; 2. Better

tonality or response; and 3. Accuracy in the lower three octaves of response.

Fig. 3 illustrates the benefits to be derived from corner placement - as

far as tonality is concerned. A 15-inch driver unit in a 6.7-cubic-foot closed box

on legs was tested four feet from the walls at a corner, on the floor in the same

place, and on the floor in a corner. The curves show the responses for these various

locations. Most noticeable is the improvement below 60 cycles, but actually of comparable

importance is the smoothing out of the 100-200 cycle range.

One must conclude from this that tonality and geometry demand corner placement

of flanking speakers.

An experiment, not reported elsewhere, concerns a corner center speaker with

wall-type flanking units, arranged in an "L" configuration. It was found that the

geometry of reproduction was unnatural. Attempts to bring the center unit into proper

geometry by increasing its signal input had the effect of causing it to "jump forward"

into monophonic prominence. It is believed that the delay effects of some 5 to 10

milliseconds cannot be compensated successfully by increasing the volume, at least

experience thus far negates the use of this configuration.

Corner placement permits the maximum separation and consequently the maximum

listening area. The listening area is proportional to the square of the distance

of speaker separation. (Refer to Fig. 4).

Outdoors, two speakers seven-feet apart could be detected as "stereo" at a distance

of more than 50 feet.5 Indoors, the distance decreased, with 14 feet

providing barely discernible stereo effect. The maximum satisfactory listening distance

was about 7 to 10 feet. Wider speaker placement insures adequate angle while addition

of the center channel insures proper focusing so that the angular stage width becomes

that of the original sound. Recall that the string quartet and soloist were properly

located on playback as well as with a large orchestra.

Microphone Placement

Early stereo demonstrations appear to have concentrated on spectacular effects

rather than reproduction of true stereo geometry. One such appears to have achieved

a "three-peep-hole" playback effect by placing three microphones too close to the

three separated sound sources.

Most current tapes and discs apparently have been cut using microphone placement

which is compatible with three-channel playback. The bulk of this author's experience

has been with two microphones. The current trend toward recording three sound tracks

and later dubbing these to two involves a technology which is an art and science

in itself. It is possible that microphone techniques which are capable of improving

two-channel playback will offer even greater benefits in playback using three channels.

Deriving the Phantom Channel

The re-combination to derive a center channel may be accomplished in various

ways. The original circuit2 is shown in Fig. 6. This represents

a "sum" combination while the "difference" circuit is shown in Fig. 5.

Systems using only two power amplifiers are based on intrinsic amplifier stability

(precluding types using "damping control" or other forms of positive feedback).

Some recordings have been encountered in which focus of the center channel required

a "sum" re-combination while others required a "difference" treatment. This option

may be taken using the circuits of Figs. 7, 8, and 9. Fig. 9 employs the Electro-Voice

XT-1 1:1 transformer. Fig. 7 involves the use of a special coil which is still

in the experimental stage and not currently in production. It is believed the frequency

at which 90-degree phase shift occurs should be placed at about 100 cycles."

Fig. 8 derives the "sum" or "difference" without the exciting current and

possible distortion of an additional transformer or coil. Fig. 10 shows a "sum"

signal derivation using a preamplifier which permits a polarity reversal. ("Polarity"

is used here rather than phase. "Phase" is the angular relation between two directed

quantities where the angle may be any value while polarity applies to the special

case where phase angles are confined to 0, 180, and 360 degrees.)

All of the circuits, except that employing three amplifiers, assume speakers

of approximately the same sound pressure output per volt of input. Impedance mismatches

have been made in "tolerable" directions and assume speakers of 16-ohm nominal impedance.

Output difference up to 6 db may be compensated by choice of output taps in two-amplifier

systems. Speakers need not be of equal "efficiency" or output per volt input, but

may differ as much as 6 db even in two-amplifier systems. Where a pad is indicated,

the "L" pad is to be preferred over a "T."

The theoretical level of the center channel has been derived as 3 db down from

the flanking channels2, but experience shows this to be a function of

environment. Room geometry has dictated center-channel levels from 0 to -9 db relative

to the flanking channels and these values may not include all extremes.

Latest Experiments

Stereo geometry experiments have been conducted comparing three independent channels

with two-track-derived three channels." These experiments are still under way but

those completed thus far indicate the two-microphone, two-track, three-channel system

approaches the three-microphone, three-track, three-channel system in performance

and exceeds the two-channel playback in accuracy of geometry.

This author is in agreement with Steinberg and Snow's' conclusions, i.e., that

the center channel is necessary for the preservation of a reasonable approximation

of the original geometry in stereo playback. Addition of the center channel permits

wider spacing of flanking speakers, culminating in the natural limiting case of

corner placement and the natural angular rotation of flanking units for complete

coverage of the wide listening area. Wide-stage stereo means wide listening area

as well and the corner-limited arrays permit full advantage to be taken of the improved

tonality afforded by corner-placed speakers and, preferably, corner-designed speakers.

References

1. Steinberg, J. C. & Snow, W. B.: "Symposium on Auditory Perspective-Physical

Factors," Electrical Engineering, January 1934.

2. Klipsch, Paul W.: "Stereophonic Sound with Two Track , Three Channels by Means

of Phantom Circuit, (2PH3)," Journal Audio Engineering Society, April 1958.

3. Klipsch,Paul W.: "Wide-Stage Stereo," IRE Transactions on Audio, July-August

1959.

4. Klipsch, Paul W.: "Circuits for Three Channel Stereophonic Playback Derived

from Two Sound Tracks (10 ways to do it)," IRE Transactions on Audio, November-December

1959.

5. Klipsch, Paul W.: "Corner Speaker Placement," Journal Audio Engineering Society,

July 1959.

6. Klipsch, Paul W.: "Three-Channel stereo Playback of Two Tracks Derived from.

Three Microphones," IRE Transactions on Audio, March-April 1959.

7. Klipsch, Paul W. & Avedon, Robert C.: "Signal Mutuality and Cross Talk

in Two-and Three-Track Three-Channel Stereo Systems," paper delivered before Audio

Engineering Society Convention, October 8, 1959.

|