|

September 1973 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Common sense never

goes out of style, especially as it pertains to safety in the presence of electricity.

Most people who have worked in the electrical / electronics realm for a while are

aware that lethal electrocution

can occur with currents as low as 100 mA when it passes through the heart. Lower

values cause progressively less profound maladies, but in practice any level of

current great enough to be felt is not a good thing. I have written before about

having received a few pretty scary shocks when working on high voltage equipment

and many lesser jolts throughout my 50± years of exposure. Other than observing

my father's being leery of using of anything with an electric cord attached to

it, my first formal instruction about electrical safety was in my vocational classes

in high school. Instructor Russ Lorenzen taught us to keep one hand in our pockets

when working on live circuits, which of course was only to be done under the rare

circumstance when it is not possible to first turn power off. In practice that often

meant when doing so would be more inconvenient than the calculated risk of electrocution

;-). Seriously, though, a very often encountered qualifying scenario is when working

inside a live circuit breaker service entrance panel where pulling the electric

meter is the only way to remove power. Doing so requires a utility worker to break

the seal on the meter socket enclosure, and besides, often shutting off every circuit

in the panel, especially in a commercial or industrial environment, would be unreasonable.

How to Avoid Workbench Hazards

Don't Be Careless When Working with Electronics Don't Be Careless When Working with Electronics

Every year, thousands of electronics professionals and hobbyists suffer the painful

and sometimes lethal effects of electrical shock while at their workbenches. Most

are lucky enough to come away from the experience with a bruise, a broken bone or

a painful memory and a new respect for the power of electricity. Those who fail

to come away from it become statistics.

These accidents need never have occurred if the victims had adopted a sensible

work plan and geared themselves physically and mentally to avoid multiplying the

shock hazard. You can minimize the shock hazard on your workbench by using a few

simple expedients and exercising good common sense.

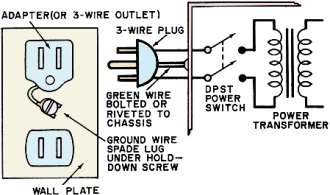

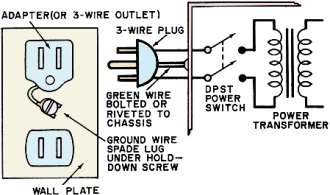

Fig. 1 - Recommended method of wiring cords and switches

on electronic gear.

In this article we will be discussing some of the practices you should adopt

whenever you work on line-powered and high-voltage circuits and equipment. We will

detail the conditions under which you should avoid working near potentially dangerous

voltages and describe what you can do to make your working environment a safer place

in which to work.

Safety Practices. Let us begin with the common denominator -

you. You can do everything possible to make your shop really safe, but if you are

a "walking disaster," accidents will follow you on the job.

First, never go to work on an electronic device-powered or not - while wearing

jewelry such as a wristwatch, ring, etc. The workbench is no place for jewelry or

other items like ties and dangling laces that can get hung up on the equipment in

an emergency or even be the cause of an emergency.

Be practical about what you wear on the job. You are at your best when comfortably

dressed. So, wear a long-sleeved shirt, buttoned at the wrists and open at the collar,

and rubber-soled shoes.

Whenever you are working on a circuit or chassis where high voltages are present,

keep your mind and eyes on what you are doing. Don't look away to observe a meter

reading or a scope waveform if you are touching a test prod to a point in a powered

circuit. Do your job the way a professional would: With the power to the equipment

under test turned off, connect the test leads. Turn on the power, take your reading,

and turn off the power. Only after the power has been turned off should you remove

the test leads from the equipment. If you do the job the unsafe way, your eyes have

to leave the work to take the reading, in which case the probe tip might slip. Chances

are that you will overreact and get yourself into more trouble.

It takes only about 10-20 μA of current coursing through the heart to cause

ventricular fibrillation, a usually fatal condition unless help and special equipment

are immediately available. Currents as low as 100 mA entering a hand and leaving

the body via the other hand or a foot can generate the fibrillatory current in the

heart. So, never reach into a high-voltage circuit with both hands, and never rest

one hand on the chassis while reaching into the circuit with the other hand. To

avoid temptation, keep your free hand in a pocket or behind your back.

If you plan to work on unpowered equipment in which high voltages are developed,

make certain that the line cord is unplugged and that you discharge all electrolytic

capacitors in the high-voltage circuits. Electrolytic capacitors can hold a potent

charge long after power is shut off; so, don't take chances. (Remember that charges

too small to be lethal can inflict secondary injuries like bruises, lacerations,

and broken bones as muscles violently and involuntarily contract upon contact. This

can be a life-saving move on the part of nature, by interrupting the through-the-body

circuit, but it doesn't help if you crack your skull against a shelf or tear your

flesh on a chassis.)

When Not to Work. Many electronics men go to work on circuits

or equipment when they should be doing something else - like resting. There are

definitely times when you should avoid going near electronic gear if you plan to

stay healthy.

Hot, muggy environments cause a worker to perspire profusely and sap energy.

A body covered with high-salinity perspiration becomes a fairly good conductor of

electricity. Not only is the resistance over the surface of the skin reduced by

perspiration, it provides a more direct current path between the skin and the interior

of the body.

Cold environments can be equally hazardous. Cold has a numbing effect on the

body, particularly in the extremities - like the fingers that hold test probes.

Fingers that lose their normally acute sense of touch can easily make mistakes and

do so all too often. Either heat the area or stay away.

Never approach a job if you are tired, angered, or emotionally upset. And don't

try to work off excess energy at your workbench. (Go lift weights or do some jogging;

it's safer.) Under these conditions, your concentration is apt to wander - which

is as bad as your eyes wandering.

Fig. 2 - How to make a workbench with a metal top safe by

addition of insulation.

The best time to go to work is when you are relaxed and alert. Stop working when

you become fatigued or bored, and take frequent rest breaks.

Your Equipment and Workshop. Many electronics men who practice

proper safety measures give little thought to their test equipment and workshops.

This is particularly true of the hobbyist who works in a basement or attic where

environmental conditions are hardly conducive to safety.

Line-powered test gear is a particularly sore point. Under no circumstances can

a line-powered instrument be considered safe if it is equipped with a two-conductor

line cord. It is even less safe if only a single-pole, single-throw power switch

is used. All two-conductor line cords should be replaced with three-conductor cords,

and all instruments should be equipped with double-pole single-throw switches. The

recommended method for wiring the cords and switches into your gear is shown in

Fig. 1. While you are at it, carefully inspect all power cords and plugs, replacing

any that are frayed, loose, or worn.

Plug three-prong plugs into appropriate sockets or into adapters to mate them

to two-conductor house wiring systems. If you use adapters, slip the spade lugs

on the grounding wire under the outlets' wall-plate mounting screw and tighten down.

When you have several instruments that have to be used simultaneously, your best

bet is to use a circuit-breaker or fuse-protected heavy-duty powerline outlet box.

In this event, you need only one adapter in a two conductor house wiring system.

If you want to be really safe at your workbench, consider installing a ground-fault

interrupter (GFI) in the bench's power system. The GFI is a fast-response device

that disconnects power from the load whenever leakage current exceeds a specific

amount (typically 5 mA). Don't install the GFI into the room's entire electrical

system, or it might extinguish the lighting when it trips - a safety hazard in itself

as you grope around in the dark and trip over things .

Finally, make your work area safe and livable. In a damp basement where the floor

is of raw concrete or in an attic where the floor is of unfinished lumber, lay vinyl

flooring. Both areas will benefit enormously from a few sheets of hardboard nailed

over exposed studs and rafters. Before installing the hardboard, however, make sure

that there is adequate weather insulation between the exposed studs and rafters.

A casement vent in the basement or a through-the-wall vent, each equipped with an

exhaust fan, to allow free circulation of air will keep either area relatively dry

and odor-free. While you are about fixing up your work area, install adequate lighting.

Any good book on home improvements will tell you how to do these things.

Wood is the best material for an electronics workbench, but if you must use a

table with a metal top, it will have to be made safe. You will need two sheets of

3/4-inch plywood cut to 1/8 inch longer and wider than the dimensions of the table

top. Cement the plywood sheets together and clamp overnight. Then top them with

a ribbed synthetic rubber runner, held in place with contact cement, to provide

a durable non-skid work surface. Finally, glue and nail a hardwood frame around

this assembly as shown in Fig. 2. When finished, the worktable surface should

slip over the metal table top. Do not fasten the work surface to the top of the

table.

If you do everything we have outlined above, your chances of being injured or

worse in your workshop will be very remote. But, again, we must caution you. Don't

relax your guard or take shortcuts. To do so, you are only inviting trouble.

Posted March 21, 2023

(updated from original post on 9/5/2017)

|

Don't Be Careless When Working with Electronics

Don't Be Careless When Working with Electronics