|

July 1964 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Details of ancient

Parthian electrochemical batteries unearthed near Baghdad by archaeologist

Wilhelm Konig, dating over 2,000 years, was reported in this 1964 Popular

Electronics magazine article. Housed in earthenware jars sealed with

asphaltum (bitumen), they featured a copper cylinder soldered with 60/40

tin-lead alloy - identical to modern electronics, prior to PB-free mandates -

encasing a corroded iron rod for electrodes, enabling electroplating of gold,

silver, and antimony via electrolytes like copper sulphate, ferrocyanides, or

lye. GE engineer Willard F.M. Gray replicated them successfully for Pittsfield's

Berkshire Museum, using iron rods for series connections. More cells surfaced in

a Seleucia magician's hut and Berlin Museum, suggesting secret artisanal use,

possibly traded as gifts to Cleopatra. Lamenting lost ancient knowledge from

conquests, the piece frames these as rediscoveries.

Babylon Battery

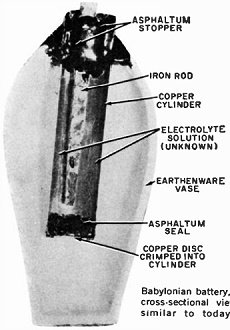

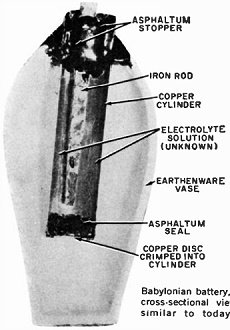

Babylonian battery, shown in the cross-sectional view at left,

is similar to today's dry cell.

By Walter G. Salm By Walter G. Salm

Electric batteries over 2000 years ago? Not really impossible, if you stop to

ponder the considerable amount of knowledge the ancients possessed. Unfortunately,

most of this knowledge was lost during various conquests and library burnings.

These early electrochemical batteries were first brought to light by a German

archaeologist, Wilhelm Konig, working for the Iraq Museum. They were discovered

in the ruins of an ancient Parthian town on Khujut Rabu'a, a hill not far from Baghdad.

The cells were apparently used for electroplating gold, and as there were no patent

laws, the processing details were passed from father to son, and kept closely guarded.

Cell Construction

The ancient cells were reported to the American scientific press in 1939 by Willy

Ley, a science historian. He described the central cell elements: a copper cylinder

containing an iron rod that had been corroded as if by chemical action. The cylinder

was soldered with a 60/40 lead-tin alloy, the same solder alloy we use today. The

electrolyte was another matter. As this was thoroughly dried by time, it's anybody's

guess. However, there were a number of usable chemicals around in those days that

could have done the job.

Batteries were built into earthenware jars such as this one.

Asphaltum was used to seal battery element in place.

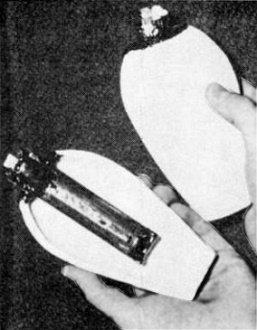

Cut-away model exposes interior of ancient cell. Vase was not

for looks, but to support elements.

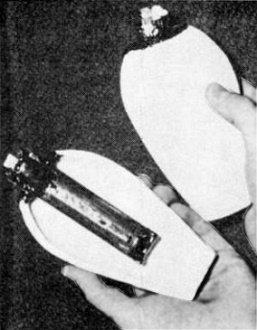

Willard F. M. Gray, an engineer at GE's Pittsfield, Massachusetts, plant constructed

replicas of these cells, and used copper sulphate as an electrolyte. Mr. Gray's

models, shown in the photographs, are now in the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield.

The earthenware jars used to house the original cells kept the cells upright, and

the tops were sealed with asphaltum, a caulking compound that cannot be duplicated

today. Mr. Gray used black sealing wax instead.

Iron and copper rods found with the ancient cells may have been used to series-connect

them for higher voltages.

Applications

Gold wasn't the only thing these pre-A.D. smiths used the cells for. They were

also able to plate silver and antimony. This, of course, speaks well for their knowledge

of chemistry, too. Some of the plating solutions they had to compound included ferrocyanides,

lye solutions and orate baths (gold dissolved in hydroxide). These chemicals were

available to the ancients, and they could have used any of them. The asphaltum that

sealed the batteries was the same material that Noah used to caulk the ark. The

Bible calls this material "bitumen" and it must have been an all-around sealing

compound, with numerous applications.

Other Finds

While the Parthians had only a limited knowledge of the electro-chemical batteries,

archaeologists have found the remains of four more in a magician's hut in the excavation

of Seleucia, a town not far from Khujut Rabu'a. The Berlin Museum had pieces of

ten more such batteries, possibly without realizing what they were.

Although Cleopatra didn't actually have electric lights in her palace, it is

entirely possible that Mark Antony presented her with gifts that he had picked up

in his travels, and that these gifts were electroplated. Surely, some of these electroplated

jewelry items must have found their way out of the Mesopotamian region and into

neighboring kingdoms.

While we are all doubtless impressed by our own technological achievements, it

gives one pause to think that one of our commonplace "modern" discoveries is not

a discovery at all, but a re-discovery of an ancient artifact! Who can surmise what

other secrets the ancients hold in shrouded mystery?

It is unfortunate that the knowledge and technology of the ancients was destroyed

before it could be recorded and saved, but each year more wonders of the old sciences

come to light. Who knows? Perhaps some day our own technology will catch up to theirs.

|