|

July 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Phased-locked loop (PLL) oscillator

circuits are the standard implementation for tunable frequency sources these days, as opposed

to LC tank circuits with either mechanical (variable capacitor and/or inductor) or electrical

(varactor) control elements. Crystal oscillators have been around for many decades, nearly

a century in fact, but it was not until the advent of PLL circuitry using solid state digital

ICs that such stability and accuracy was available across a wide range of frequencies. As

author Klaus Peter states, using a huge bank of fixed frequency crystals with selector switches,

even when using double and triple conversion schemes, is totally impractical from physical

implementation, production, and cost perspectives. These early PLL designs did not have the

convenience of single-IC circuits as are widely available today and at a very low price. The

plethora of USB-interfaced signal generators on the market now is testimony to that.

New Tuner Uses Single Crystal and Digital Frequency Synthesis

By Klaus J. Peter

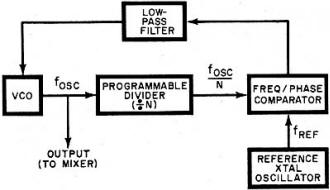

Fig. 1 - Simple phase-locked loop circuit locks oscillator to reference.

An ideal tuner must be sensitive and selective, have good spurious and image rejection,

have good capture ratio, and provide recovered audio with low distortion. Since low distortion

is achieved only when the r-f signal is properly tuned, low drift is essential to maintain

this condition. For operating convenience, a method of station pre-selection as well as the

ability to scan should also be available. The readout accuracy should be such that there is

absolutely no doubt as to which frequency or channel is being received. Manual fine tuning

to reach the center or low distortion point of a signal should be eliminated because mistuning

is probably the greatest source of distortion in FM reception.

The most obvious and simplest solution to eliminating fine tuning of the oscillator is

to use a crystal-controlled oscillator. Since the oscillator frequency is always 10.7 MHz

above the receiving frequency, 100 crystals covering from 98.8 MHz, to 118.6 MHz in 200-kHz

steps would be required for all channels. A 100-position rotary selector switch would serve

as a tuning knob and provide a mechanical or electrical readout determined by its shaft position.

This system effectively eliminates the need for fine tuning but is far too expensive since

the quartz crystals alone amount to about $200 in parts cost. Using frequency mixing techniques,

it is possible to bring the number of crystals down to 20 for dual conversion and 15 for triple

conversion but the additional switchable filter requirements also make this approach expensive.

Furthermore, multi-conversion designs may be troubled by spurious response and poor image

rejection performance due to the nonlinearity of the mixer circuits.

The Crystal Oscillator. The oscillator of the Scott 433 digital FM tuner

is crystal controlled on every frequency but uses only a single quartz crystal as a reference

standard. This is accomplished by making the oscillator part of a digital phase locked loop

(PLL) circuit. In order to understand this principle, let us look at the simplest PLL circuit

which locks an oscillator to a reference frequency.

When the system shown in Fig. 1 is first turned on, the voltage-controlled oscillator frequency

will not be exactly the same as the reference frequency. The output of the frequency-phase

comparator is an error voltage which tunes the VCO in a direction to minimize the error until

phase-lock condition is established and fosc = fref. Since the control

voltage for the VCO is ideally a dc voltage, the low-pass filter is used to remove any high

frequency components which might be present at the output of the comparator.

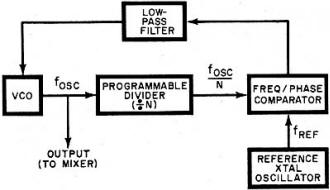

Scott 433 digital FM tuner circuitry is described in text by its designer.

In order to generate a large number of frequencies from a single reference, a programmable

divider is inserted into the PLL as shown in Fig. 2. The loop behaves as before except that

a submultiple of the VCO is now presented to the comparator and the frequency relationship

becomes

fosc / N= fref.

fosc = Nfref.

In North America, stations are assigned to fall on 100 channels from 88.1 to 107.9 inclusively

with a spacing of 200 kHz. Since the channel spacing requirement is 200 kHz, the reference

frequency of the crystal oscillator must be 200 kHz if its multiples are to fall on each FM

channel plus 10.7 MHz. Let us calculate what the divide ratio must be when the tuner is receiving

88.1 MHz or the bottom channel on the band.

The oscillator frequency will be

88.1 + 10.7 = 98.8 MHz

Substituting into the earlier equation to find the divide ratio N:

N = fosc = fref. = 98.8/0.2 = 494

This means that the voltage-controlled oscillator will be at a frequency of 200 kHz multiplied

by 494 or 98.8 MHz. The next channel higher at 88.3 MHz will require a divide ratio of 495

and so on until 107.9 MHz, the top of the band, is reached at a divide ratio of 593.

For the tuner to scan the entire FM band, the programmable divider must therefore be able

to divide from 495 to 593 inclusively.

Consequently every time a new station is desired, the divide ratio must be altered. Since

several IC counters are available with a variable modulo or programmable count sequence, one

of these is used here. The divide ratio is altered by inserting a binary code which affects

the length of the count sequence and hence the divide ratio. Each channel or frequency requires

a unique code which is presented to the divider.

The code itself is derived electronically and can be generated in a sequence which will

make the tuner appear to scan across the FM band. It actually "steps" across the band rather

than scans continuously since it only pauses (phase locks) on assigned channels. The tuner

can also be tuned or programmed by cards which present a binary code to the code generator

which in turn decodes it and passes it on to the programmable divider. The card system overrides

the other forms of sequential tuning and allows instantaneous pre-selection of stations by

using the. desired card.

Digital Frequency Readout. The tuner uses the familiar cold cathode neon

indicator tubes which were chosen for reliability, long life and reasonable cost. The display

is actuated by the same binary code which the code generator supplies to the programmable

divider to set its divide ratio. Aside from displaying the frequency in MHz which the tuner

is receiving at any given moment, the display serves as a self-checking feature for the code

generator as well as the card reader. The binary code from the code generator is decoded into

decimal form and used to drive the display; if an incorrect or non-allowable code is presented

to the divider such as one caused by a damaged card, the readout will immediately show the

error.

Fig. 2 - The programmable divider allows tuner to synthesize multiple frequencies.

The digital readout in the tuner is not simply hooked up to. a frequency counter which

counts the oscillator frequency minus 10.7 MHz. The frequency counter is a "passive" addition

which will work with any existing tuner while the PLL design is an "active" system which requires

an electronically tuned r-f section. In the passive system, manual fine tuning is still required.

With a PLL system the oscillator is forced to lock at each channel center, which always falls

exactly on the assigned frequencies of the broadcast stations.

The digital PLL system provides an r-f oscillator of crystal stability on all frequencies

plus an absolutely accurate digital display of the frequency being received. The binary code

generator setting the divide ratio allows the operator to scan the FM band manually at a preselected

speed or to let the circuit search for a station or stereo station automatically. If one station

of known frequency is desired, a pre-punched card can be used to tune to it immediately. This

feature will appeal to the discriminating music listener who has a small number of favorite

stations and selects definite programs. The scan feature on the other hand might appeal to

the less critical listener who usually scans the band until he hears something he likes.

Other Features. One of the extremely useful by-products of this system

is automatic interstation muting. The tuner just won't tune between channels. Noise muting

is also provided however for silencing empty channels; this type of muting is defeated by

a front panel switch. During the automatic "Stereo Station" scan mode, all mono stations are

muted. When tuning from one station to another regardless of which tuning mode is used, the

sound disappears without the usual transient swish or thump and reappears out of complete

silence again with the absence of annoying noise bursts and distortion.

All muting is done after the multiplex decoder by two FET series-gate switches which reduce

the signal by at least 60 dB in the muted condition without introducing a dc transient.

The r-f section in the tuner employs selected high-gain, low-noise FET's for both r-f gain

and mixer functions. A FET is also used for impedance matching and low noise in the first

stage of the i-f amplifier. Two 6-pole elliptical filters shape the passband of the i-f and

achieve a selectivity in excess of 70 dB which allows this tuner to select any one station

from a crowded area on the band.

The "Station" light on the front panel indicates the presence of a carrier and is actuated

by a zero-crossing detector coupled to the output of the ratio detector; the station light

is also a double check on the PLL and reference standard because it is actuated only if the

station is tuned to exact center. On noise which is present on empty channels, the station

light is extinguished automatically. The "Stereo" indicator will light up in the presence

of a 19-kHz subcarrier when the signal level is sufficient to give an acceptable signal-to-noise

ratio. A "Card Program" indicator shows at a glance whether or not card tuning is being used.

Aside from providing instantaneous pre-selection of station frequencies, the card serves as

a permanent memory since the code generator's volatile memory loses the station code when

power is turned off.

Trend to Complexity. The trend in consumer electronics is toward greater

circuit complexity made possible at low cost due to the use of integrated circuit technology.

The circuit designer gains flexibility in achieving performance goals and operating convenience

for the customer. Unless proper steps are taken, however, servicing of this type of equipment

can become a problem as troubleshooting time and test equipment expenditures increase drastically.

The best approach seems to center around modular construction with each module representing

a functional sub-assembly which can be replaced with no more effort than the vacuum tube in

an old TV set. Fault location is greatly simplified by the fact that each module performs

a definite function which can be monitored individually with a minimum of test instruments.

Once the faulty module is replaced by the service shop, it is sent back to the factory where

automated test facilities localize the fault to a component on the subassembly and it is either

repaired or scrapped. This module exchange policy has been used for some time and is gaining

in importance as equipment complexity increases. The customer also has the advantage of knowing

exactly how much the repair will cost if it is done after the warranty period has expired

because definite module exchange prices have been established. Even service shops with limited

facilities can repair a unit as complex as the digital FM tuner if a set of PC modules or

even another operating unit is available. Each module is simply in-terchanged with a new one

until the fault disappears.

Although the complexity of circuitry has increased, reliability has increased also. Through

the use of MSI (medium scale integration), the number of hard-wired interconnections has actually

decreased thus avoiding a significant number of failures. By screening TC's in incoming inspection,

testing assembled modules under worst case conditions before they are mounted into complete

units, and extensive life testing of finished products, the failure rate has been reduced

to a fraction of what it was a few years ago. The IC's used as building blocks in the digital

sections are of the standard variety already well proven in the computer industry and second

sourced widely.

Posted

|