|

May 1973 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

A series of three articles

appeared in 1973 issues of Popular Electronics magazine that conducted

a high-level review - or introduction if you've never seen it before - of

DC circuit analysis. In this first installment from the May issue, Professor Arthur Seidman,

of the Pratt Institute,

covers a variety of subjects starting with direct current (DC) circuit theory.

Ideal current and voltage sources, units and notations, Ohm's law, Kirchhoff's

law, resistors, capacitor and inductor charge and discharge curves, series

and parallel circuits, power calculations, conductance, and other good stuff

is covered. There is even (gasp) a bit of calculus presented.

Do You Know Your DC Circuits?

Part 1 of 1 3-Part Series Covering

DC Circuit Analysis Part 1 of 1 3-Part Series Covering

DC Circuit Analysis

By Arthur H. Seidman, Prof. of Elect Eng., Pratt Institute

Editor's Note: Whether you are an experienced designer and finished your

formal education years ago or are just starting your first courses in electronics,

here is an excellent opportunity to learn the fundamentals of DC circuit theory.

Start now, and don't miss the second and third parts in succeeding issues.

Other subjects to be covered in these series include transistors and diodes.

1. Passive Elements

A. Definition

An element is passive if it is only capable of accepting electrical energy.

(A battery, for example, provides electrical energy and is therefore called

an active element.) Examples of passive elements are resistors (R), capacitors

(C), and inductors (L).

B. Ohm's Law

The current i (amps) in a resistor R (ohms) is equal to the voltage v (volts)

across the resistor divided by the value of the resistance: i = v/R. This

is the basic statement of Ohm's law. By algebraic manipulation, one can also

write v = iR and R = v/i.

C. Voltage and Current Relations for L and C

(1) The voltage across an inductor (L) is equal to the value of inductance

(henrys) multiplied by the rate of change of current with respect to time

(amperes/second): v = L(di/dt). If i is a direct current, it does not change

with time; therefore di/dt = 0 and v = 0. (2) The current in a capacitor (C)

is equal to the value of the capacitance (farads) multiplied by the rate of

change of voltage across the capacitor with respect to time (volts/second):

i = C(dv/dt). If v is a direct voltage, it does not change with time; therefore,

dv/dt = 0 and i = 0. This demonstrates that a capacitor blocks the flow of

direct current. (3) The charge q (coulombs) stored in a capacitor is q = vC.

2. Linear Elements

A. Definition

A linear element is one that, if its input is increased by a given amount,

responds with a proportional increase. For example, if the voltage across

a linear resistor is doubled, the current flowing in the resistor is also

doubled. A nonlinear resistor is shown in Fig. 1. Note that the value

of the resistor, R (v), depends on the voltage across it. (In this article

we are concerned only with linear elements.)

B. Linear Circuits

A linear circuit contains only linear elements.

3. Notation

For DC quantities, use upper-case letters for voltage (V), current (I),

energy (W), and power (P). For time-varying quantities, use lower-case letters.

4. Ideal Sources 4. Ideal Sources

A. Definition

(1) An ideal voltage source is one whose voltage, V" is constant

regardless of the current it supplies. (2) An ideal current source is one

whose current, I, is constant regardless of the voltage across the element

to which it supplies current.

B. Symbols

Symbols for ideal voltage and current sources are shown in Fig. 2.

5. Unit Step Function

A. Definition

A unit step function, u-1 (t), is equal to 0 for t less than

0 and 1 for t greater than 0 (Fig. 3). This concept is useful in describing,

for example, the application of a direct voltage (or direct current) to a

circuit. If we let v = Vu-1(t), at t less than 0, v = 0 and at

t greater than 0, v = V. If i = Iu-1,(t ), i = 0 for t less than

0 and i = 1 for t greater than 0.

6. Circuits Containing R & C and R & L Elements

A. RC Circuits

To a direct current, a capacitor acts initially (time t = 0) like a short

circuit. (1) The product of R and C is called the time constant, T, of the

circuit: T = RC. (2) After a time of approximately 5T, the circuit is considered

to be in steady state, and the capacitor acts like an open circuit. (3) Steady

state is symbolized by t = ∞.

Ex. 1. For the circuit in Fig. 4, determine 1 at (a) t = 0, I(0) and

(b) in steady state, 1(∞). (c) What is the time constant of the circuit?

Sol. (a) I(0) = 10/100 = 0.1 A. (b) I(∞) = 0. (c) T = RC = 100 X 10

X 10-6 = 10-3 s = 1 ms.

Ex. 2. For the circuit in Fig. 4, find the voltage across the capacitor,

VC, at (a) t = 0 and (b) t = ∞. Sol. (a) Because the capacitor

acts like a short circuit at t = 0, VC(0) = 0. (b) Because the

capacitor acts like an open circuit in steady state, VC(∞)

= 10 V.

B. Functions of Time B. Functions of Time

For times between t = 0 and t = ∞, the current and voltage as functions

of time for the circuit in Fig. 4 may be expressed by:

i(t) = (V/R) ε-t/RC and vc(t) = V (1 - ε-t/RC).

C. RL Circuits

To a direct current, an inductor acts like an open circuit at t = 0 and

as a short circuit at t = ∞. The time constant is T = L/R.

Ex. 3. Referring to Fig. 5, determine the current I at (a) t = 0 and

(b) t = ∞. (c) What is the time constant for the circuit? Sol. (a) I(0)

= 0. (b) I(∞) = V/R = 10/10 = 1 A. (c) T = L/R = 0.1/10 = 0.01 s = 10

ms.

Ex. 4. For the circuit in Fig. 5, find the voltage across the inductor,

at (a) t = 0 and (b) t = ∞. Sol. (a) Because the inductor acts like

an open circuit at t = 0, VL(0) = 10 V. (b) Because the inductor

acts like a short circuit in steady state, VL(∞) = 0.

D. Functions of Time

For times between t = 0 and t = ∞, the current and voltage as functions

of time for the circuit in Fig. 5 may be expressed by: i(t) = (V/R) (i

- ε-tR/L) and vL(t) = V ε-tR/L.

7. Energy and Power

A. Definitions

(1) Energy may be defined as the ability to do work. In the mks (meter,

kilogram, second) system of units, the unit of energy is the newton-meter

or joule. One joule is equal to one watt-second. (2) Power is the rate of

doing work or the rate-of-change. of energy with respect to time. Its unit

is joules/second or watts. (3) Energy, w, is equal to the product of power,.

p, and time, t: w = pt. (4) For electrical circuits, p = vi. Since i = v/R

and v = iR, we can write p = v2/R = i2R. (5) Only resistors

are capable of dissipating energy; capacitors and inductors store energy.

B. Energy Stored in Capacitor

The energy stored in a capacitor is wC = 1/2Cv2,

where v is the voltage across the capacitor.

C. Energy Stored in Inductor

The energy stored in an inductor is wL =:= 1/2Li2,

where i is the current flowing in the inductor.

Ex. 5. A 200-watt light bulb is powered by a 120-volt DC source. Find (a)

the current required by the bulb and (b) the energy consumed in lighting the

bulb for 2 hours. Sol. (a) I = P/V = 200/120 = 1.67 A. (b) W = Pt = 200 X

2 X 3600 = 1.44 X 106 joules.

Ex. 6. Determine the energy stored in (a) a 1-microfarad capacitor across

which is 10 volts and (b) a 10-millihenry inductor whose current is 4 A. Sol.

(a) WC = 1/2 X 10-6 (10)2 = 0.5 X 10-4

joules. (b) wL = 1/2 X 10 X 10-3 (4)2 = 0.08

joules.

Note: The circuit laws, theorems, and techniques reviewed here also apply,

in general, to AC circuits.

8. Kirchhoff's Laws

A. Kirchhoff's laws provide a formal method of finding

currents and voltages in a circuit, regardless of its complexity. The laws

apply to circuits energized by de, ac, or time-varying voltage and currents.

B. Voltage Law

The voltage law states that the algebraic sum of voltages

around a closed path is equal to zero. Mathematically, ∑v(t) = 0, where ∑

is the Greek symbol for sum.

C. Series Circuit C. Series Circuit

A series

circuit is a network where the same current flows in each element. An example

of a series circuit is shown in Fig. 6.

Ex. 7. Using Kirchhoff's voltage law, find (a) the current in and (b) the

voltage across the 10-ohm resistor in the series circuit in Fig. 6. Sol.

It is necessary to distinguish the direction of current flow and the polarity

of voltage sources in the application of Kirchhoff's voltage law. The convention

used here is: (1) A minus sign precedes a voltage quantity in going around

a closed path from a low to a high potential or against the direction of indicated

current flow. (2) A plus sign precedes a voltage quantity in going around

a closed path from a high to a low potential or with the direction of indicated

current flow. (3) The assumed direction of current flow is arbitrary. (a)

Referring to Fig. 6, assume that we start at point A and go around the

closed path clockwise (with the direction of indicated current flow). Then,

according to the voltage law and the conventions we have adopted, - 100 +

(25 + 10 +15)I = 0 or I = 100/50 = 2 A. (b) From Ohm's law, the voltage across

the resistor is V = IR = 2(10) = 20 V.

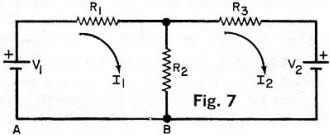

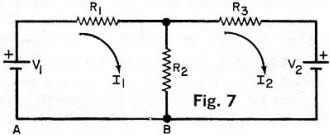

Ex. 8. Figure 7 shows a two-mesh or two-loop

network with the assumed clockwise direction of current flow in each mesh

indicated. Write the necessary equations to solve for the two currents. Sol.

For the first mesh, beginning at point A, the voltages are -V1

+ (R1 + R2)I1 - R2I2

= 0 (Eq 1). For the second mesh, starting at point B, -R2I1

+ (R2 + R3)I2 + V2 = 0 or -V2

= -R2I1 + (R2 + R3)I2

(Eq 2). Equations (1) and (2) constitute a pair of simultaneous equations.

Terms R1 + R2 and R2 + R3 are

the self resistance of meshes 1 and 2, respectively; term R2 is

the mutual resistance linking the two meshes. Ex. 8. Figure 7 shows a two-mesh or two-loop

network with the assumed clockwise direction of current flow in each mesh

indicated. Write the necessary equations to solve for the two currents. Sol.

For the first mesh, beginning at point A, the voltages are -V1

+ (R1 + R2)I1 - R2I2

= 0 (Eq 1). For the second mesh, starting at point B, -R2I1

+ (R2 + R3)I2 + V2 = 0 or -V2

= -R2I1 + (R2 + R3)I2

(Eq 2). Equations (1) and (2) constitute a pair of simultaneous equations.

Terms R1 + R2 and R2 + R3 are

the self resistance of meshes 1 and 2, respectively; term R2 is

the mutual resistance linking the two meshes.

Ex. 9. If, in Ex. 8, R1 = 1 ohm, R2 = 2 ohms, R3

= 4 ohms, and V1 = V2 = 6 V, solve for I1,

I2 and the voltage across each resistor. Sol. Substituting the

given values in Eqs (1) and (2), we get 6 = 3I1 - 2I2

(Eq 3) and -6 = -2I1 + 6I2 (Eq 4). Equations (3) and

(4) may be solved for I1 and I2 in a number of ways.

If, for example, we multiply Eq (3) by 3 and add the result to Eq (4), we

have 12 = 7I1 or I1 = 12/7 A. Substituting this value

in Eq (4) and solving, I2 = -3/7 A. The negative sign denotes that

I2 actually flows in a direction opposite to that assumed in Fig. 7.

The voltage across R1 is V = (12/7) 1 = 12/7 V; across R2,

V = (12/7 + 3/7)2 = 30/7 V; and across R3, V = (-3/7)4 = -12/7

V.

D) Current Law

Kirchhoff's current law states that the algebraic sum of currents leaving

a node is equal to zero, or ∑i(t) = 0. A node is a junction of two or

more elements. If currents flowing toward a node are taken as negative and

currents flowing away as positive, then, for example, -i1 + i2

+i3 = 0 in Fig. 8.

E) Parallel Circuits

A parallel circuit is a network where the voltage across each element is

the same (Fig. 9).

Ex. 10. For the parallel circuit in Fig. 9, determine (a) the voltage

across each resistor and (b) the current in each. Sol. (a) Applying Kirchhoff's

current law at node A, we have: -6 + V/2 + V/4 = 0 or 6 = V(2 + 1)/4 = 3V/4;

and V = 8V. (b) I2 = 8/2 = 4 A; I4 = 8/4 = 2 A.

F) Conductance

Conductance, G, is the reciprocal of resistance; thus G = 1/R. The unit

for conductance is the mho, which is ohm spelled backwards.

Ex. 11. Referring to Fig. 10, write the necessary equations to solve

for V1 and V2. Sol. From Fig. 10, V1

is taken between nodes 1 and N; with V2 between nodes 2 and N.

Node N is a common node and nodes 1 and 2 are independent nodes. Because we

have two independent nodes, two nodal equations are necessary. With the assumed

currents as shown, Kirchhoff's current law for node 1 gives: - I1

+ I2 + I3 = 0 (Eq. 5). At node 2: -I3 + I4

= 0 (Eq 6). Expressing Eqs (5) and (6) in terms of voltages and resistance,

we have -(V - V1)/R1 + V1/R2 +

(V1 - V2)R3 = 0, or V/R1 = V1(1/R1

+1/R2 + 1/R1) - V2/R3 (Eq 7);

and - (V1 - V2)/R3 + V2/R4=

0 or -V1/R3 + V2(1/R3 + 1/R4)

= 0 (Eq 8). Equations (7) and (8) can be expressed in terms of conductances:

thus, G1V = (G1 + G2 + G3)V1

- G3V2 (Eq 9) and -G3V1 + (G3

+ G4)V2 = 0 (Eq 10). Terms G1 + G2

+ G3 and G3 + G4 are the self conductance

of nodes 1 and 2, respectively; and G3 is the mutual conductance

between nodes 1 and 2.

Ex. 12. For the network in Fig. 11, determine V1 and V2.

Sol. At node 1, -10 + 0.5V1 + 0.5 (V1 - V2)

= 0, or 10 = V1 - 0.5V2 (Eq 11). At node 2, - 0.5(V1

- V2) + 0.5V2 = 0, or -0.5V1 +V2

= 0 (Eq 12). From Eq (12), V1 = 2V2. Substituting this

value in Eq 11, we have 10 = 2V2 - 0.5V2 = 1.5V2.

Solving, V2 = 10/1.5 = 6.7 V and V1 = 2V2

= 2(6.7) = 13.4 V.

Fig. 11

(To be continued)

|

Part 1 of 1 3-Part Series Covering

DC Circuit Analysis

Part 1 of 1 3-Part Series Covering

DC Circuit Analysis  4. Ideal Sources

4. Ideal Sources B. Functions of Time

B. Functions of Time

Ex. 8. Figure 7 shows a two-mesh or two-loop

network with the assumed clockwise direction of current flow in each mesh

indicated. Write the necessary equations to solve for the two currents. Sol.

For the first mesh, beginning at point A, the voltages are -V1

+ (R1 + R2)I1 - R2I2

= 0 (Eq 1). For the second mesh, starting at point B, -R2I1

+ (R2 + R3)I2 + V2 = 0 or -V2

= -R2I1 + (R2 + R3)I2

(Eq 2). Equations (1) and (2) constitute a pair of simultaneous equations.

Terms R1 + R2 and R2 + R3 are

the self resistance of meshes 1 and 2, respectively; term R2 is

the mutual resistance linking the two meshes.

Ex. 8. Figure 7 shows a two-mesh or two-loop

network with the assumed clockwise direction of current flow in each mesh

indicated. Write the necessary equations to solve for the two currents. Sol.

For the first mesh, beginning at point A, the voltages are -V1

+ (R1 + R2)I1 - R2I2

= 0 (Eq 1). For the second mesh, starting at point B, -R2I1

+ (R2 + R3)I2 + V2 = 0 or -V2

= -R2I1 + (R2 + R3)I2

(Eq 2). Equations (1) and (2) constitute a pair of simultaneous equations.

Terms R1 + R2 and R2 + R3 are

the self resistance of meshes 1 and 2, respectively; term R2 is

the mutual resistance linking the two meshes.