|

August 1966 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

A lot of innovation went into perfecting telegraph keys. The earliest keys were

the familiar "straight key"

tapping type where the operator uses a single finger to close a set of contacts

that "keyed" the transmitter for a burst of RF energy. The length of each "dit"

or "dah" was determined by the operator's dwell time. It didn't take long for someone

to improve on the scheme by designing keys that assured an adjustable, constant

length for a dit or a dah. Poor quality transmitters with lousy rising and falling

edge signatures at the beginning and end, respectively, of a CW (continuous wave)

pulse made matters worse. Constant length bursts make it easier for the person on

the receiving end to copy since patterns do not depend so much on the sender's "fist"

style. Eventually the electrical, mechanical, and human elements got good enough

that code sending / receiving speed was limited by the amount of time taken to physically

open and close the key contacts. A stronger return spring makes the contacts open

faster, but it is harder to depress and slows operation. Horace Greeley Martin,

proprietor of the Vibroplex Company, introduced the "bug" style telegraph key in

1905 to address the issue. The Vibroplex has a set of contacts on both sides of

a paddle that moves back and forth horizontally between the user's thumb and forefinger.

That removed the need for a strong spring (only enough force to center the paddle)

and allowed the operator to very rapidly shake his wrist to generate code. A newer

type bug, referred to as a paddle,

has adjustable circuitry that generates fixed proportion dits, dahs, and spaces.

They are referred to as "iambic"

due to the fixed meter (cadence) generated.

The Dit Makers -Converting Muscle Power to Morse Code Was the Job of These Old

Workhorses

By Marshall Lincoln By Marshall Lincoln

Although this statement may start an argument, the heyday of the radiotelegrapher

has passed. Since Marconi keyed his first transmitter, however, there have been

all sorts of ingenious contraptions developed to ease the job of the radio operator.

Looking back, many key designs now seem rather foolish and scarcely worth the effort

involved in learning how they were to be used.

You'll find old keys, proudly polished , exhibited in the many "wireless" museums

that dot the country. The keys shown here are on display in the museum maintained

by the American Radio Relay League, in Newington, Conn.

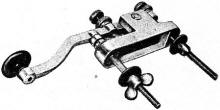

Think a "bug" is a complicated machine?

How would you like to drive this impressive unit down the 80-meter ham band? You

might call this a "double bug," although its proper title is "double lever automatic

keyer." It formed dit's and dah's automatically, like a "modern" electronic keyer,

but the operation was entirely mechanical. There were 17 adjustments to make to

tune it up for use - you had to be a good man to get 'em all done before the sunspot

cycle changed. Think a "bug" is a complicated machine?

How would you like to drive this impressive unit down the 80-meter ham band? You

might call this a "double bug," although its proper title is "double lever automatic

keyer." It formed dit's and dah's automatically, like a "modern" electronic keyer,

but the operation was entirely mechanical. There were 17 adjustments to make to

tune it up for use - you had to be a good man to get 'em all done before the sunspot

cycle changed.

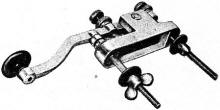

This is a "sideswiper." Also called a "cootie key," it was the granddaddy of

the modern "bug" or semi-automatic key. The sideswiper was made with a spring lever

suspended between two fixed (but usually adjustable) contacts. Both dit's and dah's

had to be formed manually by the operator. The large silver contacts on this "dit

maker" were said to be capable at handling 2000 watts.

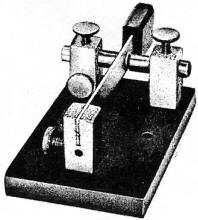

Take a look at the mounting bolts on this

baby. It's just a simple straight key that was the standard type used on United

Fruit Company vessels. The long bolts held the key securely bolted to the operator's

worktable. The contacts aren't exactly midgets, either - those sea-going spark sets

really packed a wallop. Take a look at the mounting bolts on this

baby. It's just a simple straight key that was the standard type used on United

Fruit Company vessels. The long bolts held the key securely bolted to the operator's

worktable. The contacts aren't exactly midgets, either - those sea-going spark sets

really packed a wallop.

You might call this one a bug in a box.

It's an early type of semi-automatic key which was called a "Mecograph," and is

shown here in its carrying case. It had a paddle much like those used on bugs today,

but the weight and pendulum that form the dit's are at right angles to the paddle

axis. You might call this one a bug in a box.

It's an early type of semi-automatic key which was called a "Mecograph," and is

shown here in its carrying case. It had a paddle much like those used on bugs today,

but the weight and pendulum that form the dit's are at right angles to the paddle

axis.

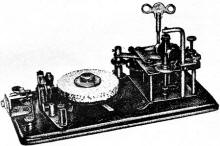

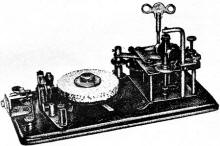

Who says "CQ" wheels are new? This old-time

"Omnigraph" was made in the early 1900's for transmitted interval signals to occupy

the frequency or channel. A spring-powered clockwork at the right (notice fly-ball

governor) turned the wheel in the center, which carried metal "code wheels." Raised

spots on the edges of the wheels caused a spring lever to close electrical contacts,

keying a transmitter. CQ, anyone? Who says "CQ" wheels are new? This old-time

"Omnigraph" was made in the early 1900's for transmitted interval signals to occupy

the frequency or channel. A spring-powered clockwork at the right (notice fly-ball

governor) turned the wheel in the center, which carried metal "code wheels." Raised

spots on the edges of the wheels caused a spring lever to close electrical contacts,

keying a transmitter. CQ, anyone?

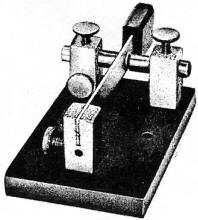

This heavy-duty key saw some hard use. Notice

the angle of the large contacts. Those big lumps of silver could handle a kilowatt

with ease. They had to. The old-time transmitters were big bruisers, and the "main

plumbing" was keyed directly. The old key slappers weren't called "Sparks" for nothing. This heavy-duty key saw some hard use. Notice

the angle of the large contacts. Those big lumps of silver could handle a kilowatt

with ease. They had to. The old-time transmitters were big bruisers, and the "main

plumbing" was keyed directly. The old key slappers weren't called "Sparks" for nothing.

|