|

February 1971 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Other than for DC

power supply applications where you might need to implement current steering

and/or redundancy schemes, there are not too many times when a combination of

transistors and/or diodes would be used for logic circuitry in place of

integrated circuits. That has not always been the case. Early packaged IC blocks

were expensive compared to discrete components, so both hobbyists and

professional designers often used a combination of technologies.

Resistor-transistor logic (RTL) and diode-transistor logic (DTL),

emitter-coupled, logic (ECL), and other variations were covered in a 1969

Radio-Electronics article by titled "How IC's Work: Integrated Circuit Logic Families."

This piece provides a little more insight into the construction of those

families and shows how to construct logical combinations using diodes and NOR

gates. As noted in my Radio-Electronics write-up, the Apollo

Guidance Computer used only 3-input NOR gates to build RTL circuits for all of

its solid state logic capability.

Discrete Components Yield Better Understanding

Part 1 of a 2-Part Story by Frank H. Tooker

Virtually all RTL (resistor-transistor-logic) integrated circuits can be duplicated

from conventional discrete components. This enables the builder to design and test

circuits at the same time - well before an IC is selected and installed. Various

logic gates, latch circuits, and half-adders are discussed in this part of the article.

The integrated circuit has been with us for barely a decade and in use in hobbyist

and experimenter circles for roughly half that time. Yet, the IC has had a profound

effect on every area of electronics, making possible the present sophistication

of modern digital equipment.

The digital computer, for example, is often viewed erroneously as a complex device

of gigantic proportions. But you have only to consider how much more complex and

larger in size it would have to be if it were assembled entirely with discrete components.

Without the IC, a digital computer could easily occupy the volume of a small house.

What is true of the digital computer is also true of all digital logic devices,

including communication, telemetry, and instrumentation systems, as well as the

digital test equipment many home enthusiasts use on their workbenches. Without integrated

circuits to simplify and miniaturize electronic devices, our space program would

still be where it was ten years ago, information processing would be slow and tedious,

and it is more than likely that digital test equipment would never have evolved.

Fig. 1 - N-input integrated circuit gate.

The purpose of this article is to provide information needed to breadboard IC

logic element equivalents, or near equivalents. "Equivalent" - as used here - refers

to the function and not the configuration of the IC and discrete circuits.

In this first of a two-part story on resistor-transistor logic (RTL), attention

is focused on logic gates. (The glossary explains the distinction between the three

fundamental types of digital logic systems - RTL, DTL, and TTL - and provides definitions

for the various technical terms used in this article.) Installment number two will

deal with the more sophisticated toggled logic circuits, including the JK flip-flop.

Virtually every RTL element consists of some form of logic gate which operates

in much the same manner as a common relay. The gate requires an input activating

force and a two-state (on/off, high/low, or logic 1/logic 0) output. Only two output

states arc necessary for digital circuits to communicate in their two-digit, or

binary arithmetic, language. Consequently, the basic elements of digital systems

are quite simple.

Compared to the 0-to-9 decimal system of arithmetic, however, binary arithmetic

requires a tedious number of operations to perform the same function and process

the same information. The extra operations, of course, require extra logic elements

which, in turn, give all digital equipment the appearance of being complex.

The actual simplicity of a digital logic element can be seen in the two-input

IC logic gate shown in Fig. 1. If only one stage of this circuit is considered,

it is the configuration of an inverter, or one-input gate, in an integrated circuit.

This gate could not be simpler, consisting of a single transistor and its associated

base resistor. A hex-inverter IC would contain 6 such inverters, all connected to

the power source through a common 640-ohm collector load resistor. (Note: Integrated

circuit designers have chosen 450 ohms and 640 ohms for the base and collector load

resistors, respectively. These values give the circuit optimum fan-in and fan-out.

The 450- and 640- ohm values used inside IC's are not commonly available in discrete

component form; when you breadboard your elements, you would use 470- and 680-ohm

resistors. These will work adequately.)

The transistors in all RTL integrated circuits are silicon NPN types with characteristics

similar to discrete computer-type switching transistors. All RTL IC's operate from

a power source of 3.6 volts within a maximum tolerance of ten percent.

When breadboarding any RTL element, keep in mind that a computer-type transistor

need not have a linear transfer characteristic since it is never operated in a linear

fashion. It is either completely cut off or fully saturated. However, it must have

certain other characteristics: excellent high-frequency response; comparatively

high saturation current gain; and 0.2 volt or less collector-to-emitter saturation

potential. The latter is important because when the output of one gate is connected

directly to the input of another gate, the output potential of the first transistor,

when saturated, is sufficiently near ground potential to insure that the second

transistor is fully cutoff.

A one-input gate is most commonly referred to as an inverter because its output

is 180° out of phase with its input. In terms of positive computer logic, when

the input is at a logic 1, the output is at a logic 0, and vice versa (logic 1 is

the complement of logic 0). In terms of negative computer logic, the 0's and 1's

change places for the on or off state of a given transistor.

It is simpler to follow positive computer logic where a logic 0 is equal to ground

or near ground potential because the logic designation coincides with the signal

level. As far as logic is concerned, however, it makes no difference whether logic

0 is represented by a near-ground potential or by some potential significantly removed

from ground. If you think of a logic 0 as represented by a cut off transistor, and

a logic 1 as represented by a saturated transistor, then negative logic can be followed

as easily as can positive logic.

Fig. 2 - N-input discrete-component logic gate.

The schematic diagram of Fig. 1 shows how simple it is to provide additional

inputs to the logic gate. The collector load resistor remains the same for each

additional input stage. Theoretically, at least, IC designers could go on adding

inputs in this fashion until the total accumulated leakage current became excessive.

In easily available IC's, four inputs - in a quad arrangement - are the most you

can get. Within reasonable limits, adding inputs has no significant effect on the

fan-in and fan-out factors of a gate.

There is nothing mysterious about resistors and transistors on an IC chip. They

function the same as their discrete counterparts. So, you can easily assemble an

inverter, a two-input gate, an n-input gate, etc., using discrete components alone.

(The circuits presented from here on arc designed to operate at speeds up to 100,000

Hz, sufficient for experimental purposes. Digital equipment used in science and

industry, of course, becomes practical only because it can operate at speeds in

the MHz range.)

Figure 2 shows how you can breadboard logic gates with discrete components. Readily

available resistor values are somewhat greater than those conventionally used in

integrated circuits, but they are close enough for the most part - especially if

you do not attempt to work your discrete-component setups close to maximum fan-out.

But when working with critical circuits, you shouldn't load your circuits too heavily

in any case.

Almost any high-speed, computer-type silicon NPN switching transistor can be

used in your circuit setups. A good example of such a transistor is the 2N2475 and

HEP56. If you are in an area where surplus parts stores are located, you might be

able to pick up quite an assortment of silicon switching transistors at bargain

prices.

In the absence of computer-grade transistors, you might try using any high-frequency

silicon NPN transistors you have around. But remember to run the input up to where

the transistor is well into saturation, and check the collector-to-emitter potential

with a meter. If the reading obtained is 0.2 volt or less, chances are you can use

the transistor in digital logic-gate service.

Being able to expand a gate is particularly useful when circuits are being assembled

on your workbench. The circuit in Fig. 3A is an expander, resembling an inverter

or one-input gate with the exception that it has no collector load resistor. Figure

3B shows how all expander can be added to an IC inverter element to make a two-input

logic gate. Simply connect the collector (output) of the expander circuit to the

output of the inverter. The input to the inverter now becomes input 1 and the input

to the expander becomes input 2. Note that the circuit is fundamentally identical

to that in Fig. 1. In a similar manner, you can add all expander to a two-input

gate to create a three-input gate, and so on.

Fig. 3 - Simple expander (A) adds inputs to gate (B).

Now, suppose you have a two-input-gate IC, you need a three-input gate, and you

have no suitable transistor on hand to breadboard the expander. You can expand the

two-input gate to a three-input gate by using a couple of germanium diodes as shown

in Fig. 4A. The diodes can be 1N191 or HEP134 types - or any diode with similar

characteristics.

The purpose of the diodes is to keep a logic signal at input 1 from entering

input 2 and vice versa. Yet each diode allows the signal at its respective input

to enter the IC left-gate input. (Note: Discrete and IC configurations can be identified

by whether or not a circle encloses the transistors. Discrete transistors are enclosed

in circles, while IC transistors are not.) If you need a four-input gate, you can

add a similar pair of diodes in the same manner to the input resistor on the second

transistor.

There can be a 0.3-0.4-volt forward voltage drop across each diode, so it is

not advisable to use diode expansion as part of the load in a maximum fan-out configuration.

The transistor expander in Fig. 3A is not subject to this limitation.

On the other hand, if you are breadboarding a two-input gate using a pair of

germanium diodes and a single transistor, as shown in Fig. 4B, you can often get

around the voltage-drop limitation by using a germanium NPN transistor (HEP641 or

similar) in the setup. However, there are significant factors that must be taken

into consideration here. First, germanium transistors can be operated in no more

than a moderate temperature environment since they perform poorly or not at all

at elevated temperatures. (The same, of course, applies to germanium diodes.) Second,

the lower the required logic level, the lower the noise immunity of the circuit.

For those setups where noise pulses or spurious signals are a particular problem,

the circuit in Fig. 4C can be of considerable value. This circuit gates with an

input logic level of 3 volts but is unresponsive to input signals of 1.5 volts or

less. Additionally, its fan-in is only about ten percent that of a gate with a conventional

input.

From now on, logic symbols will be used in many of the schematic diagrams in

this article. The logic symbols, with their equivalent electronic circuits, are

given in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4 - Germanium diodes are often used to add inputs to existing

gates (A) and (B). Typical noise immunity circuit (C) is below.

Fig. 5 - Logic symbols (at left of each circuit) are generally

used in logic flow diagrams.

Fig. 6 - Diode pair can be used to make AND gate in (A) from

three inverters as in (B). Discrete-component diagram for (B) is shown in (C); (D)

and (E) are logic and schematic diagrams for NAND gate.

A positive-logic NOR gate is a negative-logic NAND gate. From the point of view

of positive logic, the gates described thus far are all NOR gates in which a logic

1 input to either input 1 or input 2 (or both) produces a logic 0 output.

The circuit in Fig. 6A is a conventional positive-logic two-input AND gate wherein

both inputs must be supplied with a logic 1 signal to generate a logic 1 signal

at the output. This setup requires two inverters and a two-input gate to bring the

input and output signals into phase with each other. The small circles at the apices

of the logic symbols indicate inversion, or a 180° phase displacement, between

the input and output signals. Hence, two gates or inverters are needed to make the

output and input signals of the same phase.

If you have only three inverters and no two-input gate available, you can breadboard

a positive-logic AND gate with the aid of a pair of germanium diodes as shown in

Fig. 6B. An AND gate, assembled with discrete components is given in Fig. 6C.

An AND gate requires two inversions so that logic 1 inputs provide a logic 1

output. Without the second inversion, we would have a NAND gate. In the NAND circuit,

logic 1 inputs provide a logic 0 output. Given in Fig. 6D and in Fig. 6E are the

logic diagram and discrete component schematic diagram for NAND gates.

In comparing the AND and NAND gates, note that a double inversion is equal to

no inversion at all.

In the preceding logic-gate circuits, output logic directly follows input logic.

In the simple two-input gate, for example, a logic 1 at either of the two inputs

produces a logic 0 output. Removal of the logic 1 input by sending the input to

logic 0 produces a logic 1 output.

There are, however, applications where it is desirable to turn on one gate by

applying a signal to one input and turn oft the gate by applying a signal to the

other input. Once such a circuit is energized, it will remain turned on even after

the excitation signal is removed. It will also be unresponsive to succeeding turn-on

signals. Similarly, once it is turned off, it will remain off and be unresponsive

to subsequent turn-off signals. Such a device can be thought of as it "latch" and

is known as an RS (for reset-set) flip-flop.

The fundamental circuit of a latch ran be represented by a pair of inverters,

with the output of one inverter connected directly to the input of the other as

shown in Fig. 7 A. Because inversion occurs in each inverter, it is obvious that

when one side of the circuit is on, the other must be cut off. It is equally obvious

that the on side must remain on and the off side remain off unless something is

done to make the system change states. No provision is made to effect any such control

in the simple circuit shown.

A more practical latch or R.S flip-flop is shown in Fig. 7B. Here a pair of two-input

logic gates is used. One input of each is used for the feedback, and the other is

used for control. A logic 1 signal applied to input 1 sends output 1 to logic 0

and output 2 to logic 1. The circuit then remains in this state - held there by

its own feedback and disregarding any further application or removal of turn-on

signals - until a logic 1 signal is applied to input 2, at which time the output

logic reverses itself.

Only a brief pulse at the proper input terminal is needed to trigger and latch

the circuit in either state. The waveform of the control pulse is not especially

critical. In fact, an RS flip-flop is often used to "shape" a logic pulse by converting

it to a square wave with very steep sides.

If a logic 1 signal is applied to both latch inputs simultaneously, both outputs

will go to logic 0. The final state of the latch will then depend on which of the

two inputs is the last to be removed. Ordinarily, a latch is not operated in this

mode; but if a particular setup calls for such operation, there is no reason why

it cannot be employed.

The circuit in Fig. 7B is given in discrete-component form in Fig. 7C. Depending

on what components you have available, you can breadboard a latch in several different

ways. It can consist of a dual two-input gate IC, a pair of inverters in an IC (plus

a couple of expanders), or four individual transistors if necessary.

Fig. 7 - Two inverters are employed in fundamental latch circuit

(A). More practical latch is RS ftip-flop illustrated in diagrams in (B) and (C).

Fig. 8 - Practical latch using inverters is illustrated in diagram

(A); discrete-component circuit for power-gated, or buffered-input, latch is shown

in schematic diagram (B).

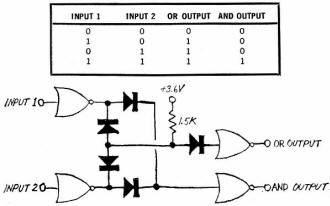

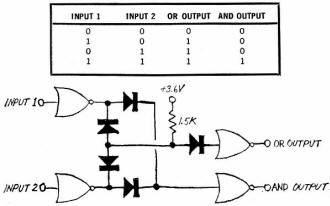

Fig. 9 - Simultaneous AND/OR gate at left employs diodes and

simple inverters. All possible inputs and their outputs are listed in truth table

(above).

Fig. 10 - Simple addition of diode D and resistor R to the simultaneous

AND/OR gate yields the Exclusive OR circuit that is shown at right.

Fig. 11 - Half-adder/subtracter has DIFFERENCE and BORROW outputs

in addition to the SUM and CARRY of Exclusive OR.

If you need a latch circuit and have only a single pair of computer-type silicon

NPN transistors, or a couple of spare inverters in a hex-inverter IC, you can assemble

the fundamental latch circuit in Fig. 7B and gate or trigger it from one state to

the other with germanium diodes. The circuit in Fig. 8A illustrates how this can

be done. It is possible to do this for the same reason that it is possible to use

a pair of diodes for gate expansion, in which the two diodes on each side of the

setup operate as positive-logic OR gates.

In the circuit of Fig. 7B, turn-on of a transistor is accomplished by pulling

its collector down to near ground potential. It then turns on as a result of cross-coupling.

In the circuit of Fig. 8A, the same result is obtained by driving the base positive

with a logic 1 input. Minimum input logic level is about 50 percent higher than

that required by the circuit in Fig. 7B, however.

A power-gated or buffered-input latch circuit is shown in Fig. 8B. A virtue of

this circuit is that, with light loading, it will trigger reliably from one state

to the other with an input current as low as a few microamperes. For a minimum-load

setup, input resistors R can have a value as high as 500,000 ohms. It is important

to note, however, that input logic level must be about 3 volts. Input current is

exchanged for input voltage in this setup. The "high-step" input can help to improve

noise immunity.

You can assemble a power-gated latch using a pair of inverters in a hex-inverter

integrated circuit, or you can breadboard the whole circuit with four transistors

as shown in the schematic diagram. You should use this circuit whenever you have

a sufficient input-logic voltage level but inadequate input-logic current to operate

a more common latch. Do not attempt to get around the higher input logic level requirement

by using a germanium transistor for triggering. Leakage current through a germanium

transistor is too great for this application.

The fan-in of the circuit if Fig. 8B is so low that, when used in the majority

of digital logic layouts, it can be considered as practically an open circuit. It

is especially useful as an exceptionally low-power input start/stop switch in counter

and time-lapse applications.

An element which can supply the OR logic function and the AND logic function

of two inputs simultaneously is of considerable value in digital circuitry. For

one thing, with only slight modification, it forms the foundation for an Exclusive

OR, or Half-Adder, element.

In the simultaneous AND/OR gate of Fig. 9, five diodes and four one-input gates

perform all of the required logic functions. At the output of the two input inverters,

one pair of the diodes provides the AND function, while the other pair, together

with the 1500-ohm resistor, provides the OR function. A logic 1 is obtained at the

OR output when a logic 1 is applied to input 1, input 2, or both inputs simultaneously.

A logic 1 is obtained at the AND output only when a logic 1 is applied to both inputs

simultaneously.

A state table for the circuit is also provided in Fig. 9. This state table lists

all possible in-puts to a digital logic element or device and the outputs which

result from these inputs.

A half-adder or Exclusive OR Logic circuit is shown in Fig. 10. The circuit is

obtained by adding resistor R and diode D to the OR circuit of Fig. 9. (In some

cases the diode may be omitted.)

In the circuit in Fig. 10, the Exclusive OR output is the SUM output, and the

AND output is the CARRY. As shown by the state table in Fig. 10, the circuit provides

a logic 1 at the SUM: output when a logic 1 is supplied to either - but not both

simultaneously - input. When a logic 1 is supplied to input 1 and input 2 simultaneously,

the output is a logic 0, as it is when both inputs are logic 0. The outputs of the

circuit demonstrate the fact that a logic 1 added to a logic 0, or vice versa, produces

a sum of 1 and a carry of 0. A logic 1 added to a logic 1 produces a sum of 0 and

a carry of 1.

A half-adder is required to sum only two logic inputs, whereas a full-adder must

sum two inputs and a carry, for a total of three logic inputs. (A full-adder consists

of two half-adders, plus some additional circuitry. Details of this circuit would

simply digress from the subject of this article. Also, a full-adder would be impractical

to breadboard in any event.)

Now, if we label input 1 with an A and input 2 with a B, then in a half-adder/subtracter

in which B is subtracted from A, the following happens: First, the SUM output is

identical with the DIFFERENCE output, such that the SUM or DIFFERENCE output supplies

the Exclusive A OR B function. Next, the CARRY output supplies the A AND B function.

And, finally, the BORROW output supplies the BAND A-COMPLEMENT function.

The circuit of a half-adder/subtracter, which can be readily breadboarded, is

given in Fig. 11. It consists of five diodes, four inverters, and a dual two-input

gate (or the equivalent in discrete form). This particular setup also supplies the

complement of the SUM or DIFFERENCE output.

As you can see from the preceding, there is little need - or reason - for you

to make a large financial investment in digital IC's if you want to experiment with

and design logic elements and systems. Discrete components, and maybe a few commonly

used gate IC's, will suffice for your breadboarding arrangements. You can select

your IC's from the knowledge you gain through experimenting with discrete component

elements. This is really the best and safest route to go when experimenting with

integrated circuit digital logic techniques.

Glossary of Digital Logic Terms

Adder: Switching circuit that combines binary information to generate the SUM

and CARRY of this information.

AND: This Boolean logic expression is used to identify the logic operation where,

given two or more variables, all must be logic 1 for the result to be a logic 1.

DTL (Diode-Transistor Logic): Logic is performed by diodes with transistors used

only as inverting amplifiers.

Exclusive OR: A logic function whose output is 1 if either of the two input variables

is 1 but whose output is 0 if both inputs are 1 or 0.

Fan-in: A figure denoting the input power required to drive a logic element satisfactorily.

Fan-out: A figure denoting the power output of a logic element with respect to

logic element inputs.

AND Gate: All inputs must have 1-level signals at the input to produce a 1-level

output.

NAND GATE: All inputs must have 1-level signals at the input to produce a 0-level

output.

NOR Gate: Anyone input or more than one input having a 1-level signal will produce

a 0-level output.

OR Gate: Anyone input or more than one input having a 1-level input will produce

a 1-level output.

Half Adder: A switching circuit which combines binary information to generate

the SUM and CARRY. It can accept only the two binary bits to be added.

Inverter: A circuit whose output is always 180° out of phase with its input.

(Also called a NOT circuit.)

Negative Logic: Logic in which the more negative voltage represents the 1-state;

the less negative voltage represents the 0-state.

Noise Immunity: A measure of the sensitivity of a logic circuit to triggering

or reaction to spurious or undesirable electrical signals or noise, largely determined

by the signal swing of the logic.

RTL (Resistor-Transistor Logic): Logic is performed by resistors. Transistors

are used to produce an inverted output.

TTL, T2L (Transistor-Transistor Logic): A logic system evolved from

Diode-Transistor Logic in which the diode cluster is replaced by a multiple-emitter

transistor.

Posted January 22, 2019

|