May 1958 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Just as today's generation

of engineering students grew up with and are totally accustomed to and proficient

at using computers, smartphones, positioning devices, CAE software, and various

combinations of the aforementioned, so have the latest cadre of pilots grown up

with GPS and electronic flight charts and planners in the cockpit. The difference

is that whereas engineering students are not still required to learn to use a slide

rule and a drafting table to earn an engineering degree, pilots are still required

to learn to navigate using primitive (not meant derisively) instruments and ground-based

navaids to earn a pilot's license. That's not a bad thing, though, because whereas

if your graphing, 2500-function calculator quits working, the only thing at risk

is your test score if you happen to be taking an exam. However, if your electronic

navigation fails while in a limited visibility environment or in controlled airspace,

you had better be able to do some seat-of-the-pants flying or you could be in deep

doo-doo. This 1958 article from Popular Electronics magazine presents the

newfangled

TACAN

(TACtical Air Navigation) and Loran

(LOng RAnge Navigation) systems recently introduced (at the time) by the CAA (Civil

Aeronautics Authority), which is now the FAA (Federal Aeronautics Administration).

It was to dead reckoning navigation what the HP-35 calculator was to the slide rule.

Finding Your Way in Space

By Brooks Currey, Jr. By Brooks Currey, Jr.

It's a long haul from the old sea dog to today's jet

There was a time when a well-moistened forefinger was a man's only navigation

instrument. The cool side told him the wind direction-and thus, his course. Today,

man relies on the thin metal "forefingers" jutting from high-speed high-altitude

aircraft to keep him informed on position, direction, velocity and other data so

necessary to flight. And satellites circle some 300 to 400 miles above the earth

- spring-loaded "forefingers" busily transmitting spatial information back to us.

The evolution of navigation from an uncertain art to a specialized science has

been long and arduous. Its basic principles have always existed - they only awaited

discovery. By necessity, navigation has always tagged along in the wake of mathematical

and astronomical development. The ancient Greeks, we know, taught that the world

was round and that any position on its surface could be determined by latitude and

longitude. Basic principles, therefore, did not mystify man so much as the instruments

used to verify them.

Direction by Radio

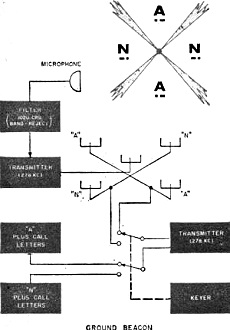

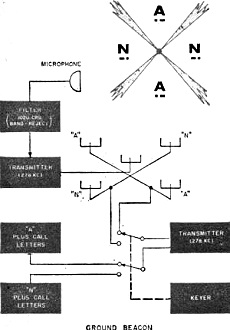

Block diagram shows what's behind the "beam" that pilots fly

on the CAA network of airways.

The development of electronic aids to navigation begins within our present century

- in the early 1900's when Marconi's wireless made radio direction-finding the first

electronic aid.

Early shipboard direction finders were simple loop antennas, with a tunable receiver

(100 to 1800 kc.), a set of earphones, and an azimuth indicator. To operate, the

navigator simply tuned in a radio station of known position, rotated the loop to

minimum gain, and then read the relative bearing on the azimuth indicator. By using

several such stations - the more the better - and drawing the bearings on a chart,

the ship's position was located at the intersection of the bearings.

As refinements were made on radio direction-finding equipment, the speed and

range of aircraft were steadily increased. Aerial navigation amplified existing

problems of navigation, and introduced many new ones. For instance, the time allowed

to compute position decreased in direct proportion to the increasing flight speed.

A part of this new problem was solved by the low-frequency radio range.

Now standard for nearly all airplanes, radio range equipment makes use of a network

of ground stations and a receiver in the airplane. In operation, four radio beams

of approximately 3° width are transmitted along the CAA (Civil Aeronautics Authority)

airways - intercontinental "super-highways" 10 miles wide which are divided into

1000' altitude levels.

Basically, the ground station has two pairs of transmitting antennas, each matched

pair being placed at diagonal corners of a square. One pair transmits "A" (dit dah),

the other pair "N" (dah dit) , The signals are transmitted in a figure-eight pattern.

A and N signals overlap to provide equal signal intensity along the four 3° beams.

The pilot tunes his receiver to the proper station frequency, between 200 and

400 kc., and listens for the station's call letters, e.g., LGA for La Guardia Field,

New York. Once identified, the pilot hears either A or N in keyed intervals. (The

N signal is always assigned to the quadrant containing true North to minimize confusion.)

If the pilot hears an N, he knows he is off the beam, and he turns left or right.

In so doing, he notes that the original N grows into a steady tone where the dah

dit and dit dah overlap. When the pilot cannot distinguish A or N, he is "on the

beam."

Radar and Racon

Simplified diagram below shows how the Racon (RAdar beaCON) operates.

Note use of scope.

Plotting a ship's position by Loran makes use of the intersection

of two hyperbolas, which are obtained by tuning in two pairs of stations.

The big impetus to electronic aids came during World War II, with the advent

of radar. Using narrow beams of microwaves of 1 to 12 cm. in wavelength, radar measures

the time it takes an energy pulse to travel out, echo off an obstruction and return.

One mechanization of this effect is Racon (RAdar beaCON), which provides the air

navigator with both distance and bearing information on a standard PPI (Plan Position

Indicator) scope.

Airborne Racon equipment includes a primary radar operating on a frequency in

the 200- to 10,000-mc. frequency range. The ground beacon consists of a secondary

radar containing a receiver, time-delay unit and transmitter.

In operation, the navigator "interrogates" the ground beacon with a pulse from

his radar. This triggers a coded pulse from the beacon which is transmitted in all

directions. The navigator observes the beacon response on a PPI scope in much the

same manner as he observes targets.

To differentiate between Racon signals and target echoes, the beacon signals

are coded as a series of pips as detected by the PPI scope. Thus, bearings to the

beacon can be taken, and distance measured. Effective range of Racon operation is

limited only by the horizon or line-of-sight distance.

A more specialized system is DME (Distance Measuring Equipment), though bearings

to the ground beacon are not given. Fundamentally, the ground equipment for DME

is like that used for Racon. The airborne equipment, however, differs in that the

distance is shown on a dial indicator instead of a PPI scope. Because this indicator

is susceptible to beacon interrogation pulses by other aircraft, the airborne equipment

contains a sweep-search circuit in addition to a tracking circuit. In operation,

the airborne transmitter sends out a 936- to 986-mc. beam. A separate receiver antenna

picks up the beacon and any other transmissions.

Airborne VOR. Should the navigator wish to determine course direction and not

distance, he can use one of several omnirange systems: low-frequency, v.h.f. or

u.h.f. The omnirange equipment provides the navigator with accurate courses either

off or on the airways.

With the VOR system (V.h.f. Omnidirectional Range), the navigator or pilot selects

a station from a chart published by the CAA. He next tunes in the frequency of the

selected station by means of a dial, and checks the coded or voice call of the station

with that given on the chart. The magnetic bearing of the station from the aircraft

is set into the system by means of a selector wheel; the bearing of the station

is thereafter retained at all times until changed to a new station.

Two other very essential parts of the airborne VOR system are the "left-right"

and the "to-from" indicators. Once the magnetic bearing of the station has been

selected, the pilot-navigator checks the "to-from" indicator to determine if his

aircraft is flying toward or away from that station. The "right-left" indicator

then guides him to the station by means of "flying to the needle." If the needle

points to the left of the correct course, the pilot should turn left until it centers

once more; if it points to the right, he turns in that direction.

Loran. Another major electronic aid to navigation emerging from World War II

was Loran (LOng RAnge Navigation). Though primarily associated with sea rovers,

Loran is also used successfully for aerial navigation. It is the only method that

does not rely on dead reckoning to compute position but rather on the hyperbolic

functions of analytic geometry.

Assume that we are standing some distance from two mountains. We find that mountain

A is 100 miles from us, and B is 150 miles away. The difference in distance is 50

miles. Now we can move so that the difference in distances always remains 50 miles,

but only if we move in a hyperbolic path. This is the basic method used in Loran,

the major addition being that there must be at least two pairs of "mountains." By

using two pairs, two hyperbolas result, and the point at which they intersect is

the ship's position.

Tacan, shown atop the mast of the new supercarrier "U.S.S. Forrestal,"

and u.h.f. radio by Federal Telecommunication Labs (left circle) play important

role in America's air-sea defense.

Flying laboratory of Federal Telecommunication Labs flight-tests

Tacan under all conditions.

In standard Loran, a pair of ground transmitters sends out pulses at the rate

of either 25 or 33 1/3 per second. Antenna output is about 100 kw. at frequencies

between 1700 and 2000 kc. Another nearby pair of stations, on the same frequency,

provides the navigator with the second hyperbola.

Aboard ship, the navigator has a conventional superheterodyne receiver with four

broad channels which are fixed-tuned. The navigator selects any pair of stations,

tunes in and reads the time difference between the two signals on a cathode-ray

tube. He selects at least one other pair and repeats his computations. The intersection

of the two hyperbolas is then found on a specially gridded Loran chart. A good navigator

can obtain a fix in less than five minutes.

Range of Loran navigation varies from 700 miles during the day to twice that

at night; reflection of waves from the ionospheric layer in the evening gives this

range boost. Ground waves, of course, are primarily used because of their accuracy,

though tables have been prepared to take into account any sky wave reflections during

nighttime operation.

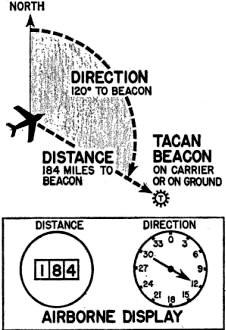

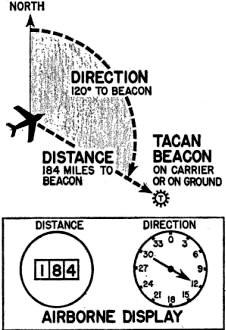

Tacan

Illustration of how the Tacan system works.

Last and latest on the list of electronic aids to navigation is all-weather Tacan

(TACtical Air Navigation). Tacan operates in the 1000-mc. band with 126 clear-frequency,

two-way channels available, each channel being spaced 1 mc, apart. In the 1025-

to 1150-mc. band, 126 frequencies are available for air-to-ground transmission;

for ground-to-air transmission, 63 frequencies are available within the 962- to

1024-mc. band, and 63 more are in the 1151- to 1212-mc. band.

In operation, the plane transmitter sends a distance interrogation. This pulse

is retransmitted by the beacon, and electronic measurement of the elapsed time interval

is converted to distance in miles. Azimuth bearings are determined by measuring

the phase difference of a periodic transmission of a main and auxiliary reference

burst from the beacon. Identification of the station is made by keyed Morse characters

at regular intervals.

We've come a long way in advancing the science of navigation to a safe, dependable

means of traveling from here to there. There's always the chance that a tube can

blow, or an amplifier can malfunction, and throw the whole system out. But we'll

have to admit that it beats holding up a wet forefinger to the wind.

Posted August 2, 2022

(updated from original post

on 3/13/2013)

|

By Brooks Currey, Jr.

By Brooks Currey, Jr.