Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Few homeowners in the era

of television antennas on the roof had any knowledge at all about how the antenna

and twin lead transmission line system worked. Even those who were familiar with

it only knew the basics like keeping the transmission line away from metallic objects

and properly terminating the ends. I have seen photographs from servicemen of

twin lead laying in aluminum guttering and along the top of chain link fence

rail, and amazingly, the TV set still received a fairly good picture. That must

have been in areas with exceptionally strong signals. This article in a 1970 issue of Popular Electronics

magazine

described a method for optimizing the antenna and transmission line in terms of

impedance matching and using very low loss open ladder line to optimize signal strength

to the receiver. It is exactly the subject (received signal strength) I recently lamented about being often

ignored when discussing aspects of antennas and transmission lines.

No Snow in June: Match Your TV Antenna to Receiver for Best Possible

Picture

By George Monser By George Monser

Good TV reception is not obtained by accident;

it is carefully sought for and designed into your antenna system. You can get the

best antenna and lead-in cable money can buy, but if the antenna is not impedance-matched

to the cable and/or the cable is not matched to the TV receiver, you might just

as well be using outdated "rabbit ears." This is especially true for color TV reception

- and not just in the "fringe" reception areas.

Everything in your TV receiving system must be just perfect, and the only way

you can make sure that it is is to do the job right - the first time. But do not

think that you have to be a TV antenna / transmission line expert to set up a receiving

system. With the help of the information provided in this article, you can set up

the best possible antenna system.

The Loss Factor. Nothing is perfect. No matter whether it is

an automobile engine or an electronic circuit, every system suffers from some type

of loss which reduces its efficiency. While you cannot completely eliminate receiving

system losses (known as signal attenuation), you can limit them to an acceptable

level.

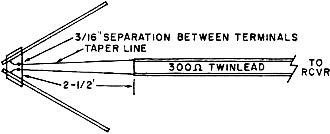

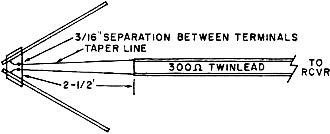

Fig. 1 - Transformers are cut to specific lengths for individual

channels or for multichannel band.

To demonstrate how loss becomes a critical design factor, consider a 300-ohm

folded dipole antenna (tuned or cut to any TV channel) connected to a length of

300-ohm twin-lead cable. Very little loss would occur between the antenna and cable

for the channel to which the antenna is tuned. But for all other channels in the

TV band, the loss might be as high as 3-4 dB; and over the complete band, an average

loss of 2 dB would be typical, enough to cancel the characteristic 2-dB gain of

the folded dipole (favorably oriented) antenna.

Now, consider a resonant 300-ohm folded dipole, reflector, and several director

array (representative of most commercial TV receiving antennas). An estimated 2-dB

loss would occur at the antenna/cable connection due to the lowering of the dipole's

impedance. (The effect of placing a reflector and directors in close proximity to

the folded dipole is to lower the 300-ohm characteristic impedance of the dipole

to about 70-100 ohms). But since this antenna array provides 6-10 dB of gain, a

2-dB loss, severe in our first case, can usually be acceptable, particularly in

good reception areas.

For both cases cited above, the cable lead-in loss, assuming about 40' of twin-lead

at VHF, amounts to between 0.6 and 1 dB. Hence, the total loss in antenna signal

strength is 3 dB. This means that only 50% of the antenna signal power would be

delivered to the TV receiver.

Fig. 2 - Insulator spacers support gradual tapers when matching

600-ohm open line to 300-ohm cable.

Reducing the losses. The choice of improving the antenna-to-transmission

line match basically involves inserting an impedance-matching transformer between

antenna and line. The drawing in Fig. 1 illustrates the makeup of one type

of transformer you can use. It is easy to fabricate and consists of two lengths

of 300-ohm twin-lead cable.

The decision of whether to fabricate your own transformer as opposed to buying

one that is commercially made should depend on the end results. Tests made with

both types show that at the 70-MHz frequency of channel 4, the commercial ferrite-core

balun lowers the signal level by about 2 dB, while the quarter-wave, twin-lead homebrew

transformer improves the signal level by 1.5 dB.

Lead-in attenuation, the other loss (amounting

to less than 1 dB) can be slightly reduced, but not without considerable effort.

Here, two possibilities exist: transition from the antenna to a home-brew 600-ohm

open-wire lead-in and back to 300 ohms at the TV receiver; or transition from the

antenna to home brew 1"-diameter, 77-ohm coaxial line and back to 300 ohms at the

receiver. Neither of these alternatives will yield a line loss less than 0.3-0.5

dB, which hardly seems worthwhile by itself. However, if a choice were to be made,

it would probably be easier to stay with a balanced line and use 600-ohm open line.

(Fig. 2 illustrates how this can be accomplished with #16 wire and a wire separation

of 4" to yield a line loss of about 0.25 dB/100' at 88 MHz, or less than 0.15 dB

for a typical 40' run. ) Lead-in attenuation, the other loss (amounting

to less than 1 dB) can be slightly reduced, but not without considerable effort.

Here, two possibilities exist: transition from the antenna to a home-brew 600-ohm

open-wire lead-in and back to 300 ohms at the TV receiver; or transition from the

antenna to home brew 1"-diameter, 77-ohm coaxial line and back to 300 ohms at the

receiver. Neither of these alternatives will yield a line loss less than 0.3-0.5

dB, which hardly seems worthwhile by itself. However, if a choice were to be made,

it would probably be easier to stay with a balanced line and use 600-ohm open line.

(Fig. 2 illustrates how this can be accomplished with #16 wire and a wire separation

of 4" to yield a line loss of about 0.25 dB/100' at 88 MHz, or less than 0.15 dB

for a typical 40' run. )

You may be wondering when and where it is advantageous to use these methods for

improving signal transfer. As a general rule, they should be employed in "fringe"

reception areas to improve weak TV channel reception. When making your own transformer

or transformers, refer to the Table for the proper quarter-wave transformer lengths

to use for each TV channel in the VHF spectrum. The lengths listed were computed

assuming standard 300-ohm twin-lead cable with a phase factor of 0.84, which is

typical for polyethylene-jacketed twin-lead.

Fig. 3 - Gradual taper matches 300·ohm twin-lead cable to

150-ohm impedance of Pyramidal Antenna.

Now, take three practical examples to show how to improve TV reception. In the

first example, suppose you have a good quality commercial antenna array and wish

to improve reception on Channel 4 by inserting a transformer section between the

antenna and a 300-ohm twin-lead line. Select the transformer length section from

the Table; in this case, 36" is indicated. Cut two pieces of twin-lead cable to

exactly 36" (plus about 1/2"extra at each end). Strip away 1/2" of insulation from

each end of both cables. Then, connect the lengths of twin-lead in parallel with

each other (see Fig. 1).

Insert the transformer section between the antenna and twin-lead lead-in cable.

This should yield an improvement of 1.5 dB in signal strength and a noticeable improvement

in Channel 4 fringe-area reception.

For our second example, suppose you use the same antenna and want the best possible

reception. Rather than running 300-ohm twin-lead cable, try using lower loss 600-ohm

open line. This can be done fairly easily by following the instructions detailed

in Fig. 2. At both the antenna and TV receiver, the line must be tapered gradually

to the 600-ohm spacing of the open line. When completed, the installation should

yield about a 2-dB improvement in signal reception, slightly better than in the

first example.

Fig. 4 - Open line matches two Pyramidal Antennas to 300-ohm

cable. Note half twist in 600-ohm line.

As a final example, assume you are planning to erect the Pyramidal TV/FM Antenna

("Build The 'Pyramidal' TV/FM Antenna," Popular Electronics, July 1969). This antenna's

impedance is about 150 ohms, which means that 300-ohm twin-lead cable is reasonably

ideal to use. However, for the ultimate match, you should insert a tapered section

of line between the antenna connecting terminals and the 300-ohm twin-lead lead-in

cable as shown in Fig. 3 to improve reception by about 0.5 dB.

The added complication of tapering the line in the last example might not be

justified, considering that this antenna has a nearly flat gain characteristic of

10 dB for all VHF TV channels.

Finally, suppose that even 10 dB of gain is not enough to provide quality fringe-area

reception. You could stack two Pyramidal antennas as shown in Fig. 4 to obtain

13 dB overall gain. Here, the individual antenna connecting point impedances can

be tapered to 600 ohms and then paralleled, providing an ideal match to the 300-ohm

twin-lead cable line to the receiver. In the illustration, the center-to-center

spacing between the antennas is 5'. Of course, the antennas could just as easily

be placed side by side to yield the same resultant gain; but erection on a single

mast is usually easier to implement.

Now that you have been apprised of good receiving system basics, you can start

designing your own system. And with the warm weather here, what better time is there

to tackle the job?

Posted March 5, 2024

(updated from original post

on 5/14/2017)

|

By George Monser

By George Monser