|

June 1971 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

As the planet's population grows older and

people have an increasing amount of disposable income and spare time, the opportunity

to engage in nostalgic endeavors has gone up. That includes collecting,

restoring, and operating equipment and peripherals that were the mainstay of their

lives during their

halcyon days of youth. In recognition of the new marketing opportunities,

industries are popping up to feed the frenzy. Look no farther than

eBay and the

amount of vintage items available for purchase - at ever increasing prices.

Having myself been an eBay buyer of memorabilia from my early model airplane, model

rockets, and electronics hobbies, I have watched prices soar in many cases. Turntables

(aka phonographs, or for the lowbrow types, record players) are being manufactured

again and vinyl records are bring pressed for some of the most popular 1960s and

1970s groups. Articles like this one are prime fodder for those wanting to resurrect

their stuff. I recently restored a 1970s-era turntable that was part

of a Reader's

Digest

special that fit my budget as a 16-year-old.

* C-141 Turntable made by

CSR, and the

Model 800-XR AM/FM Radio + 8-Track Tape Player

15 Things We Do Know About Phono Cartridges

How to Interpret Manufacturers' Specs How to Interpret Manufacturers' Specs

By J. Gordon Holt

Who was the first person to suspect that it was impossible for a phono cartridge

to track perfectly the indentations in a tiny groove on a recording? Possibly it

was Edison since he undoubtedly encountered the problem. (Though the mechanical

arrangement and materials he used were quite different from those we know today.)

At any rate, through the years it has been calmly accepted that perfect tracking

is impossible.

For a while, designers of reproduction systems simply made the stylus do what

they wanted it to by increasing the tracking force until the stylus had to stay

put in the groove. .This had its obvious disadvantages; and, though today they still

recognize the fundamental dilemma, designers have been learning what the problems

are and finding better ways of circumventing them than by the use of brute force.

Improvements in cartridge design are by no means the least important in the changes

that have been made to get better tracking. While no cartridge is yet perfect, the

past few years have seen an end to the worst imperfections that made disc reproduction

an audiophile's headache. However, in picking a cartridge, be aware that they are

not all the same - and not all equally good. So check yourself out on these fifteen

points (arranged alphabetically for ready reference):

Getting the Cartridge Mounted

All four of the stereo phono cartridges shown on this month's

cover use slightly different mounting techniques. Manufacturers have refined the

process of cartridge mounting to virtually eliminate tracking error and still insure

ease and convenience in performing what was once a nuisance undertaking. At right

is the Empire 999VE/X, one of the more highly rated cartridges in $79 (list) price

bracket. Two sizes of molded plastic screws are provided to secure cartridge clip

to special mounting bracket (not shown). Cartridge is then easily snapped in place

and leads connected. Stylus removal is also quite simple and nameplate guard shown

in photo protects stylus in transit. Practically every cartridge you buy includes

mounting hardware and some form of stylus protection.

Frequency response graph above was made from test measurements

on an Empire 999VE/X. Note the relatively smooth top curve which indicates the over-all

left channel response. The lower curve shows response in the right channel due to

crosstalk from the left channel-indicating stereo separation. A graph of phono cartridge

response is usually published in magazine evaluation reports.

Cartridge is the Danish import from B&O labeled SP 12 and

selling for $69.95 (list). Like the Empire above it has an elliptical stylus. Note

the removable wedge supplied by the manufacturer to correct cartridge mounting in

a record changer where the record stacking would drastically alter the preferred

15-degree vertical tracking angle.

The Shure M91E cartridge has an elliptical stylus with a metal

guard - shown here under the photographer's index finger. Cartridge is partially

disengaged from "Easy-Mount" snap-in bracket which would normally be attached to

tone arm head or plug-in shell. As mentioned elsewhere, cartridges are supplied

with a variety of mounting hardware and a few examples are shown here - mounting

screws (two types with American and British threads), washer/spacers, and lead clips.

Most record players and changers are sold with clips soldered to the fine wire leads

passing through the tone arm - and color-coded to boot. Mounting has been simplified

by standardizing on 1/2" (12.7 mm) center-to-center for the two retaining screws

that hold the mounting bracket to tone arm shell.

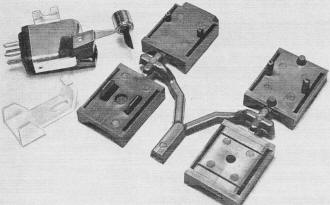

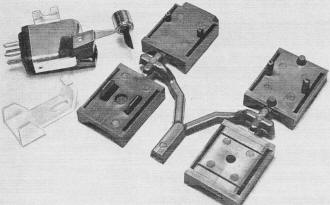

Pickering and Company has carried phono cartridge mounting ease

one step further by supplying the buyer a variety of individualized "Snap-In-Mounts"

cast from plastic (shown above with connecting plastic still in place). Starting

from lower left and going clockwise, the mounts are for Dual, BSR, Garrard, and

BSR Single Hole Heads. The cartridge itself is snapped into place on reverse side

of each mount. Stylus guard has been removed and is seen near the cartridge. Note

also the dust brush that is attached to cartridge. This is Pickering's model XV-15/750E

cartridge selling for $65, list.

Paralleling the efforts of cartridge manufacturers to simplify

mounting, record player/changer manufacturers frequently provide additional information,

mounting hardware, or even a special plastic guide. This is the tone arm cartridge

mounting shell for a Dual 1219 - note the clips soldered to connecting wires. The

guide (upper right in photo) is used to align accurately the depth and the stylus

overhang to provide minimum tracking error.

Compliance. As the stylus rides in the groove of a record, there

is a great deal of actual contact pressure between the two. This pressure is a result

of nothing more than the applied tracking force (which see) in an unmodulated groove.

When the groove starts pushing the stylus around, contact pressures can rise considerably

above 24 tons per square inch and the amount of rise depends on how much the stylus

resists the groove's efforts to move it. When the resistance to movement is significant,

groove destruction does take place, and the stylus starts to rattle around between

the groove walls to produce the familiar shatter of tracking distortion.

For many years, cartridge designers were convinced that both record wear and

tracking distortion stemmed from excessive stiffness of the stylus's flexible mounting.

Manufacturers tried to "out-compliance" one another until some styli were barely

rigid enough to keep the tone arm following the stylus movement. Today, compliance

is no longer the limiting factor in track ability of most cartridges - although

some designs intended for use in second-rate tone arms are made to have less compliance

than the top-flight precision products. High compliance didn't solve the track ability

problem anyway; it just helped. Obviously, something else was involved, and the

culprit now seems to be stylus inertia or moving mass (which see).

Distortion. One of the difficulties in evaluating cartridge

performance is the lack of meaningful measurements for audible distortion. Audio

testing organizations customarily publish harmonic and intermodulation distortion

figures, but these do not gauge what we hear as tracking distortion. They only measure

things which usually (but not always) accompany it. Trackability measurements are

more to the point, but these too are useful only for comparisons between different

cartridges, since it is possible for one pickup that is tracking better than another

to sound as though it were tracking worse - purely as a result of differences in

other aspects of the reproduced sound.

Very small amounts of amplifier distortion can make tracking distortion sound

much worse than it really is, as can high-frequency peaks in the cartridge and/or

loudspeakers; while a response dip in the upper frequency range can make a cartridge

sound as if it were tracking more cleanly than it actually is.

Durability. Few good cartridges will withstand a clumsy "finger-dusting",

but the days when an initially excellent pickup would go to pot in a few months

because of hardening of the flexible stylus suspension seem largely behind us. With

today's stylus-saving low tracking forces, though, many cartridges will start to

sound sour for this reason long before the stylus shows audible signs of wear. This

is a bit of an annoyance but it is better than having a worn stylus chewing up discs

before the wear becomes audible. Styli should be checked once a year anyway - just

to make sure.

Elliptical Styli. The elliptical stylus was a result of observations

that, while high-frequency modulations are best followed by an extremely small-radius

stylus, radii below a certain size tend to ride in the bottom of the groove instead

of staying propped up between the groove walls. Combining small side radii with

large front and back radii produced the elliptical tip.

Ellipticals do generally sound cleaner in the inner grooves of "difficult" discs

(compared to spherical styli), but the gain is not achieved without some losses.

Because the stylus/groove contact area of an elliptical is smaller, contact pressure

at a given tracking force is considerably higher. Reducing the tracking force can

help to offset this, but it cannot cause a concomitant decrease in contact pressure

against the walls of a modulated groove since the compliance and moving mass figures

of an elliptical cannot be made any better than those of a spherical. As a consequence,

the 0.7 X 0.2-mil elliptical that is tracking cleanly at around 1 gram will do more

damage than a 0.7-mil spherical tracking at 3 grams.

Only when the spherical is starting to mistrack on passages where the elliptical

is clean will their rate of record wear be about the same. And a good spherical

will track the vast majority of discs of serious music as cleanly as a good elliptical.

So light tracking force alone is no guarantee of low record wear; the tracking force

must be equated with groove/stylus contact area.

Frequency Response. Of the qualitative measurements that can

be made on cartridges, a check of frequency response reveals the most information

about how a cartridge actually sounds - or how it makes the record sound. The sound

should, of course, be as much as possible like that from the master tape from which

the disc was cut, but the recent mania for improved trackability has tended to obscure

the fact that most current designs do not produce sounds like those from the tape.

And much of the blame for this lies with the elliptical stylus.

Because of the differences in groove-contact characteristics, ellipticals tend

to have a broad response dip in the "brilliance" range that sphericals do not. Thus

ellipticals sound rather muted and "soft" by comparison. One of the most highly

respected top-priced ellipticals, noted for its clean tracking, has a substantial

dip in the brilliance range which, apart from making it sound dull, makes it sound

cleaner tracking than it is.

A second factor which is somewhat against ellipticals results from the fact that

recording studios use spherical cartridges in judging what they're putting on their

discs. The improved high-frequency tracing of the elliptical causes a rising high

end on discs that were cut to sound flat.

Some ellipticals do sound quite "tapey," though two of the most accurate disc

reproducers available (Decca 4RC and Stanton 681A) are spherical.

Magnetic Attraction. This was a problem when some cartridges

(Ortofons, Deccas) were used with iron or steel turntable platters and the cartridge's

magnet would draw it toward the platter causing a drastic and inconsistent increase

in tracking force. It is seldom a problem today since virtually all transcription

turntables and many record changers have aluminum platters. If in doubt, check the

platter before using it with a cartridge that has its magnet or pole pieces close

to the stylus tip.

Moving Mass. This is another term for inertia - which is the

mechanical characteristic that makes any object "want to" retain its present state

of motion (or rest). When a disc groove is undulating 20,000 times per second (half

cycle of a 10,000-Hz signal), it takes little stylus inertia to make the groove's

task an impossible one. The lighter the stylus and its supporting member, the more

readily it follows the groove's high frequency undulations, the less record wear

there will be, and the cleaner the sound will be. Unfortunately, lightness entails

fragility, so a practical stylus assembly must be a compromise. This is one area

in which different cartridges have significantly different attributes and trackabilities.

Noise. Until the vinyl disc was invented, subtleties of noise

like amplifier hum and hiss were usually covered by the noise of the shellac record

surface. Today's disc is virtually noiseless (when new), so the temptation to play

it at high listening levels reveals hum tendencies that might have gone unnoticed

as recently as five years ago. In response to this, cartridges and turntables now

have better shielding than ever before so that, with a few notable exceptions, it

is no longer necessary to "mate" cartridge and turntable for minimum hum.

Price. The picture here has changed from what it was a few years

ago when you had to pay top price for a cartridge that wouldn't butcher your discs.

Prices at the top are still about what they were five years ago, but the money buys

you a better cartridge. And of course, now you can buy a high-compliance, low-mass

light-tracking cartridge (such as the Goldring G-850) for under $10.

Record Wear. Low tracking force in itself is not what makes

a cartridge easy on record grooves. What is important is the ability to track with

a low force without incurring mistracking during loud passages since this is an

indication that the stylus compliance is high enough and its moving mass is low

enough to offer minimum resistance to the groove's thrusts.

Obviously, stylus-to-groove contact pressure is lowest on each groove when the

total applied force is equally divided between the two contact points. When the

stylus encounters a modulation it can't follow readily, it tends to press more heavily

against that groove wall and less heavily against the other. There still may not

be serious groove damage, though, since vinyl is resilient enough to spring back

somewhat after such an assault. But when the stylus meets a really impossible modulation,

it tends to plow right in and lose momentary contact with the other wall of the

groove. Each time it regains contact, it does so with tremendous pressure and an

audible click. It is a rapid succession of these clicks that causes the shattering

sound of acute mistracking. And the groove can't take this kind of abuse. Each click

is a sign that the stylus has plowed too deeply into the modulation for the vinyl

to recover and the resulting permanent indentations in the groove will continue

to sound fuzzy under any condition.

Since the groove is V-shaped, high tracking force helps to overcome the tendency

toward momentary losses of contact with either groove wall, thus making the sound

cleaner. But if the stylus is still plowing into modulations, fairly clean tracking

is no assurance that the record isn't being damaged.

It is the ability to track cleanly at a low force that is important, rather than

the actual tracking force. A high tracking force accelerates record wear to a degree

but the damage is not usually as great as that incurred when a cartridge is allowed

to mistrack on an occasional disc. That is why, even though a cartridge may be able

to track most discs cleanly at 3/4 of a gram, record wear may be less when tracking

force is higher - perhaps 1 gram.

Separation. Nearly all modern stereo phono cartridges with pretensions

to fidelity have more than the 25 dB of separation through the mid-frequency range

that is needed to achieve subjectively total channel isolation. "When separation

appears to be less, it is usually that way on the disc. Cartridges do still vary

rather widely in high-end separation, and those with substantially less than 15

dB separation at 10 kHz can be expected to exhibit some wandering or lack of specificity

in directional information.

Stereo separation is a touchy subject among manufacturers, so advertised claims

are often more optimistic than factual. This information is best gotten from test

reports in magazines.

Signal Output. A source of noise in some earl? stereo cartridges

was their extremely low signal output. Most preamps have a certain amount of hum

and/or hiss, which may become audible if the volume control has to be turned up

to make the signal loud enough. The answer in most cases was to feed the low-output

cartridge through a step-up transformer, which was itself a potent source of hum

and frequently gave such a high output level that the preamp was driven to the verge

of overload.

Most cartridge designers now recognize the limitations of preamps and provide

a nominal cartridge output of about 1 millivolt (per cm/sec of recorded signal velocity).

It is still wise, though, to check a cartridge's rated output before buying to anticipate

potential noise or overload problems. There is no status value in output ratings

so manufacturers' specifications are usually accurate.

Tone Arms. The advantages, shortcomings, or incompatibilities

in a tone arm influence the performance of any cartridge. With the exception of

Acoustic Research, manufacturers of pivoted tone arms now seem to agree that bias

compensation is necessary for optimum cartridge performance - though there is less

consensus as to the proper amount of compensation that is needed. (Generally, it

is best set experimentally.)

Otherwise, there have been surprisingly few developments in tone arms in recent

years. Most manufacturers seem to feel there is no room for improvement - which

has been proved wrong by the few really improved designs that have appeared. One

eminently successful approach has been the viscous-damped "unipivot" arrangement

typified by the Audio & Design and Decca "International" tone arms. Both have

many audible advantages and some purely mechanical disadvantages and have not proved

to be as popular as they deserve to be. The former has been discontinued; the latter

is available through several sources in the U.S. or directly from dealers in England.

Trackability. This is a term widely used by Shure Bros. in their

promotional material after they devised a scheme by which tracking ability could

be measured. A trackability test shows usually in the form of a graph, how much

recorded level a cartridge can handle (at a given tracking force) throughout the

audio range before it starts to lose intimate groove contact. It is thus an indirect"

measure of both compliance (affecting trackability at all frequencies) and moving

mass (affecting mainly high-frequency trackability), in terms that matter the most

to the user: tracking cleanness and record wear. Obviously the two do go hand in

hand.

Tracking Force. It has long been known that tracking force was

directly related to record wear ; but only in the last few years have researchers

been learning just how it is possible for a "featherweight" 2-gram cartridge to

wear grooves. The trouble, it seems, is that while we think in terms of force, the

groove must contend with pressure.

Since the groove wall is (nominally) a flat surface and the stylus tip is round,

they contact one another at a microscopic point (actually two points - one on each

side of the groove). Pressure is force per unit area, so if these contact points

were true points, with zero area, the contact pressure (force per unit area) from

that 2 grams would be infinitely high! Fortunately, the vinyl is flexible enough

to let the stylus sink into it at the contact points, making each point about 3/10,000

of an inch in diameter (with 0.7-mil stylus at 2 grams force). This reduces the

contact pressure against each groove wall to a mere 48,000 lb (24 tons) per square

inch!

Since vinyl normally collapses when applied pressure exceeds 14,000 lb/sq in.,

nobody has yet been able to explain how a disc can survive a single play; but the

prevailing attitude of researchers seems to be: "Accept it and be thankful."

What's In Store? There are no breakthroughs in cartridge development in sight.

The best we can look forward to is even lighter (and more fragile) stylus assemblies

that will give cleaner tracking and more transparent, open sound. Perfect tracking

is still not in the cards.

Posted May 29, 2019

|