|

June 1974 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Believe it or not, there

are still people out there - engineers and hobbyists - who design circuits using

discrete transistors. Sure, there is a plethora of integrated circuits that combine

multiple functions into a single package that performs often nearly like ideal components,

and for a lot less money than building an equivalent circuit from individual components.

Still, sometimes a lone transistor with a couple biasing resistors will do the job,

and sometimes the designer just wants to do something different. There are also

plenty of instances where you need to find a replacement of a failed transistor

that has similar form, fit, and function. This article from a 1974 issue of

Popular Electronics magazine might be just the aid you need if you have found

yourself in need of selecting a transistor. Of course if your application is for

high frequency, there are parameters to consider other than those presented here,

but it's a good start.

Transistor Selection Guide for Experimenters

Fig. 1 - Reverse and forward biasing requirements are shown

for npn and pnp transistors.

Understanding transistor circuit characteristics eliminates trial-and-error approach

By Jon L. Turino

Selecting a transistor for a specific circuit application involves considerably

more than just picking a device at random and using trial and error to determine

whether or not it will work. Proper device selection requires that the ratings and

parameters of a transistor be known and that the importance of these characteristics

in the application be understood.

As readers doubtlessly know, the bipolar transistor is normally forward biased

from base to emitter and reverse biased from base to collector (Fig. 1). In

the active mode of operation for the transistor, a small change in base current,

IB, results in a much larger change in collector current, IC.

Transistors also have two other modes of operation - cut off and saturated. In the

cut-off mode, only leakage current flows through the transistor. In the saturated

mode, maximum current flows, limited only by the external components. Even though

we use a transistor primarily in the active mode, we can illustrate many parameters

much more clearly by considering the cut-off and saturated modes.

Parameters and Characteristics. Here are ten transistor characteristics that

should be taken into account when a device is being selected (or when a circuit

is being designed around it). Refer to the proper drawings in Fig. 2 for pictorial

definitions of the parameters.

(1) VCBO: This is the collector-to-base breakdown voltage in the reverse-bias

condition. If the collector-to-base voltage is allowed to exceed the breakdown value,

the transistor may be destroyed. Always select a transistor whose VCBO

rating exceeds the highest voltage expected to exist in the circuit between the

base and collector.

Fig. 2 - Transistor is shown cut off (A), saturated (B),

and in normal mode (C).

(2) VEBO: This is the emitter-to-base breakdown voltage in the reverse-bias

condition. If this value is exceeded, the transistor may be permanently damaged;

so, select a transistor whose VEBO exceeds the maximum voltage that will

exist in the base-to-emitter circuit. (In most "small-signal" analog circuits, the

base-emitter voltage seldom exceeds about 0.8 volt in either the forward or the

reverse directions. Hence, if this parameter is not specified, it will normally

not be cause for concern.)

(3) VCEO: This is the maximum allowable voltage from collector to

emitter with the transistor reverse biased (cut off). The VCEO of the

transistor should exceed the power supply voltage if the transistor is to operate

safely. Alternatively, the supply voltage for the circuit should be maintained at

less than the VCEO.

(4) ICBO: This is the leakage current from collector to base when

the transistor is reverse biased. This parameter is of major importance because

it increases rapidly with increases in transistor temperature. It can affect the

biasing of the transistor stage and, if excessive, cause increasingly large current

flow that can result in "thermal runaway", ultimately leading to destruction of

the transistor. Select a transistor whose ICBO is less than 0.001 times

the normally expected collector current. (Usually, silicon transistors have very

small ICBO ratings. Nevertheless, it is wise to double check.)

(5) VCE(SAT): This is the voltage from collector to emitter when the

transistor is conducting maximum current and further increase in base current will

result in no further increase in collector current. This voltage is the minimum

potential that must be maintained between emitter and collector if transistor action

is to continue. It is usually specified as a specific current, IC(SAT),

and should not exceed the power supply voltage minus the peak-to-peak expected collector

voltage swing.

(6) VBE(SAT): This is the base-to-emitter voltage when the transistor

is saturated. It is usually specified at a specific current, IB(SAT),

and is important primarily in switching circuits, although it does affect the biasing

of analog circuits.

(7) IB(MAX): This is the absolute maximum base current that can safely

flow into the transistor. Care must be taken to insure that the circuit will not

cause base current in excess of IB(MAX) to flow, and, conversely, the

IB(MAX) rating of a device must always exceed the maximum expected base

current.

(8) IC(MAX): This is the absolute maximum collector current that can

safely flow in the transistor. If it is exceeded, the device is likely to destruct.

The IC(MAX) rating should exceed the maximum value of collector current

that can ever flow in the circuit.

(9) P(TOTAL): The total (maximum) power that a transistor can safely

dissipate should never be exceeded. The actual power in a circuit is equal to VCE

X IC when the transistor is biased in the active mode. (The base-emitter

voltage and current also contribute to total power, but they are usually negligible

with respect to VCE X IC.) In most circuits, it is wise to

choose a device whose P(TOTAL). rating is 2 (VCE X IC

).

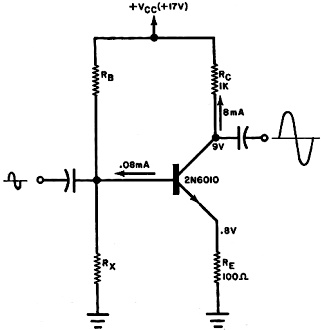

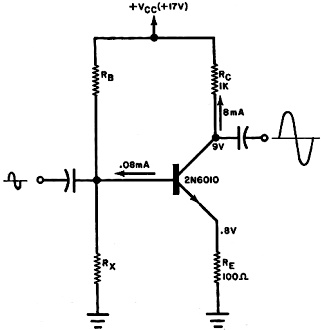

Fig. - 3 This diagram shows how the various parameters are

used in designing a circuit.

(10) HFE This is the current gain of the transistor when in the common-emitter

configuration (shown in Figs. 1-3) and is usually referred to as the transistor's

beta (β). Beta is defined as the ratio of collector current to base current (β

= IC//IB) and is one of the most important of a transistor's

parameters. It determines the achievable circuit gain and the required biasing resistor

values. It might be specified as a range of values (10 to 100) or as a set of values

at specific collector currents (50 @ 1 mA, 20 @ 10 mA, etc.). To select a beta value

for a given transistor, calculate the value of collector current required in the

circuit and the base current available. In any circuit like that shown in Fig. 2C,

beta must exceed the ratio RC/RE but must not be so large

as to allow the transistor to saturate. In a new design, the minimum beta is the

most critical parameter, since the biasing can be tailored for any specific value.

Using The Parameters. The circuit shown in Fig. 3 should help in tying together

all of the seemingly unrelated parameters. With this circuit, we will illustrate

an actual design procedure and demonstrate how each parameter relates to the design.

Let us assume that we need a circuit with a voltage gain of 10 and a peak-to-peak

output swing of 12 volts across a 1000-ohm resistor (RE). We calculate

RE as being 1000/10, or 100 ohms. (Since voltage gain AV =

RC/RE, RE = RC/AV.)

There will be 12 volts peak-to-peak across RC and 1.2 volts p-p across

RE. So that VCE(SAT) does not affect the circuit, add 3 or

4 more volts to the required total potential from the power supply. Make VCC

equal to 12 + 1.2 + 3.8, or 17 volts. With a VCC supply voltage of 17

volts and RC + RE equal to 1100 ohms, the maximum collector

current will be 17 volts/1100 ohms, or 15.45 mA. With the transistor properly biased,

there will be about half of this value (about 8 mA) of collector current. VCE

will be 17 volts - (8 mA X 1100 ohms) = 8.2 volts. Total circuit power, then, is

8.2 volts X 8 mA = 65.6mW.

Now specify a value of 100 for the

transistor's beta. At this point, we can select a transistor with the following

minimum characteristic values (right). Now specify a value of 100 for the

transistor's beta. At this point, we can select a transistor with the following

minimum characteristic values (right).

VCE(SAT) and VBE(SAT) are not critical; IB(MAX)

= IC(MAX)/Beta.

You now have enough information to begin looking through a transistor manual

for an npn transistor with parameter values on the safe side of those listed above.

Let us assume that you settle on a 2N6010 transistor with the following characteristics

(left). You now have enough information to begin looking through a transistor manual

for an npn transistor with parameter values on the safe side of those listed above.

Let us assume that you settle on a 2N6010 transistor with the following characteristics

(left).

A comparison of these characteristics with our circuit requirements reveals that

the 2N6010 transistor will more than adequate-ly met our needs. All that is necessary

now is to compute the correct values of RB and RX using conventional

means, and to check out the circuit.

There is a lot of leeway in the selection of a proper transistor for a circuit.

The more conservatively rated the transistor is for a specific application, the

better the probability of the circuit operating almost forever. When it is necessary

to select a replacement transistor, just analyze the circuit for its important parameters

and select a new device whose characteristics fit the requirements.

Posted February 22, 2024

(updated from original post on 5/15/2017)

|

Now specify a value of 100 for the

transistor's beta. At this point, we can select a transistor with the following

minimum characteristic values (right).

Now specify a value of 100 for the

transistor's beta. At this point, we can select a transistor with the following

minimum characteristic values (right).  You now have enough information to begin looking through a transistor manual

for an npn transistor with parameter values on the safe side of those listed above.

Let us assume that you settle on a 2N6010 transistor with the following characteristics

(left).

You now have enough information to begin looking through a transistor manual

for an npn transistor with parameter values on the safe side of those listed above.

Let us assume that you settle on a 2N6010 transistor with the following characteristics

(left).