|

May 1973 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Those of us who have been

making measurements on electrical and electronics equipment for a long time are

well aware of the need to be certain that the ground (common) lead of a piece of

test equipment - oscilloscope, multimeter, or other instrument - is never connected

to a point in the circuit that is above ground potential. Doing so can be dangerous

and/or destructive. If the test point is above ground potential, connecting the

ground lead to it creates a direct short to ground, which can destroy the device

under test (DUT) or at least cause the measured signal to be altered. In the case

where the DUT has no ground reference of its own via a safety ground connection,

connecting the ground lead to a point not electrically common to the chassis (or

enclosure) will cause the chassis to assume a potential other than ground. Many

technicians received shocks (sometimes fatal) while servicing old ungrounded (2-prong

power cord) TVs that did not have isolation transformers at the input. Connecting

a meter between a set of transformer secondary windings where neither had a direct

connection to the chassis would cause the chassis to "float" to a potential above

or below ground (depend on polarity), sometimes to lethal levels.

Understanding Ungrounded Oscilloscope Measurements

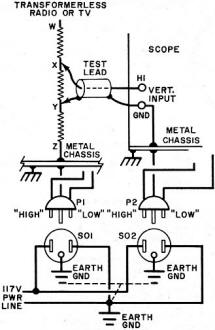

Fig. 1 - In transformerless circuit, ground return on point

V can a short across Y-Z element.

By Virgil A. Thomason

Making scope measurements across ungrounded components can present some problems.

Here are the reasons - and some answers.

When we measure a voltage in a circuit, we don't always take into account what

we are actually measuring. For instance, we might say that a power supply's output

is 50 V dc with 0.75 V ac ripple; or the output signal at a transistor amplifier's

collector is 5 V ac. In these, and just about all voltage measurements, what we

really mean is that the power supply's output is 50 V dc with respect to ground

(or chassis common); the ripple is 0.75 V ac with respect to ground; and the amplifier

output is 5 V ac with respect to ground. Thus, what we are really measuring is the

voltage at a given point - with respect to a common point.

Since a voltage is the potential difference between two points, the two points

have to be identified. For convenience, we generally use chassis ground as the second

point.

But what if we want to measure the voltage across a component both sides of which

are above ground? This presents a problem - many problems, in fact. Obviously, one

difficulty is the lack of a convenient, easy-to-get-at chassis for a connecting

point. More important, however, are the possible bad effects of connecting both

leads of a test instrument to ungrounded points.

Of course, occasions such as this do not occur often; but when they do, knowing

the proper procedure can make the job easier and prevent undesirable effects such

as overloaded circuits and noise pickup.

Not a Simple Test. Measuring a voltage between two ungrounded

points is not always a simple matter. Assuming that an oscilloscope is being used,

one does not merely connect the test probe and ground lead at opposite ends of the

ungrounded component - certain precautions must be observed. Consider the following

examples.

Assume that we have a conventional scope which has a three-wire power cord. For

safety, the scope chassis is tied to the third wire and ground. Because the signal

input "ground" terminal is also common with the chassis ground, it too is tied to

the third wire in the power cord. Now, let's say we're testing an ac/dc radio or

a transformerless TV receiver; the chassis being tested is tied to the low side

(ground) of the power cord. So we have the situation shown in Fig. 1. The chassis

are tied together through the power line system.

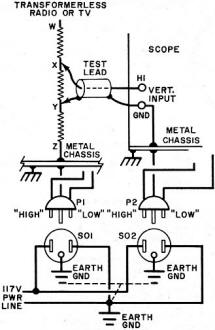

Fig. 2 - With power transformer in circuit, connecting scope

ground return to point V can put an ac shunt across V-Z.

As long as the scope's ground test lead is connected to the tested chassis (point

Z in Fig. 1), the chassis are tied together, the grounds are tied, and we have

a good, safe test setup. Notice, however, what happens when the scope's ground test

lead is connected to a point above ground potential (point Y in Fig. 1). The

portion of the circuit between Y and Z is effectively shorted out by the ground

circuit through the two chassis and the power line ground.

This, of course, could severely disturb the circuit operation and possibly damage

the components in the network. The same ground problem could also occur with a scope

that has a 2-wire power cord if the low side is tied to chassis ground.

Now, assume that we have a scope with a three-wire power cord and we're testing

a TV receiver with a power transformer and a conventional 2-wire ac connection.

As shown in Fig. 2, the low side of the ac line is connected to the chassis

through a large resistance (commonly 2.2 megohms). Of course, not all equipment

have this resistance - some are entirely isolated - but it is important to know

whether it is there or not. With the circuit shown in Fig. 2, there is an ac

shunt effectively placed across part of the circuit under test.

The ac path inside the receiver is from point Z to the chassis, to the transformer

secondary, through stray primary-to-secondary capacitance, to the transformer primary,

to the ac line. This ac shunt can cause problems, especially with high frequency

measurements. (For all of the above situations, tying the ac line to an ungrounded

point can introduce noise into the circuit.)

Fig. 3 - Simple differential amplifier has inputs A and

B and output A-B.

Still another problem is encountered if the scope does not have its chassis tied

to the power line ground. In this case, connecting the scope ground lead to a point

above ground could make the chassis "hot."

So there are several undesirable effects that we want to avoid - dc shunt, ac

shunt, noise pickup, hot scope, etc. Let's examine ways to make ungrounded measurements.

Conventional Scopes. The only way to get ideal ungrounded measurements

is with a special scope with a differential amplifier input. Next best is to use

a scope with a dual-trace amplifier input and an "A-B" mode. But even with a conventional

scope, there are ways to reduce some of the undesirable effects - if not completely

eliminate them.

First, we must know our scope. Is the chassis grounded to the ac line? Also,

note the grounding on the device under test. If it has been determined that the

scope will not cause a dc shunt, we must realize that the circuit being tested can

still be disturbed by the scope's ac loading. Noise and hum pickup should be taken

into account. Even if the scope chassis is not directly tied to the line ground,

it can put noise into the tested circuit; the scope's large metal cabinet acts as

an antenna and picks up noise.

We can use an isolation transformer with the scope to prevent dc shunts. This

also reduces the ac shunt; but because of the transformer's primary-to-secondary

capacitance, ac loading and noise will still occur. However the capacitive reactance

does reduce loading and noise - as compared to a direct line without a transformer.

In using an isolation transformer, remember that the scope chassis can be hot when

the signal ground lead is connected to an ungrounded point.

Fig. 4 - Using a differential scope to make a measurement

across an ungrounded component.

Oscilloscope Differential Amplifier. Because the output of a

differential amplifier is the difference of its inputs, we can use it to measure

the voltage across a component-which is a potential difference. The significance

of a differential voltage measurement is that it can be used for an ungrounded component

without encountering the bad effects noted above.

Figure 3 shows a simplified block diagram of a differential amplifier. It consists

of two identical amplifiers. They have the same gain, but one inverts its input.

The outputs are then combined by algebraic addition; and since one output is inverted,

the total is A - B.

Differential measurements are less common than conventional single-input measurements

so scopes with differential amplifier inputs are few. Many scopes of the plug-in

type have differential amplifier inputs. The electronics enthusiast, experimenter,

or service technician could build a differential amplifier to feed a conventional

single-input scope.

In practice, the signal high leads are connected to the two points to be measured.

No common ground connection is required so the two low leads are not used. Usually,

they are shields on the test probes.

For safety reasons, however, the scope and device under test may be connected

with a grounding wire. However, this connection must not be the signal low leads

or the shields, to avoid ground loops.

It should be pointed out that the differential amplifier scope is not the same

as a dual-trace scope. The latter has two amplifiers, each with its own input. Electronic

switching alternately feeds the output of each amplifier to the scope's vertical

deflection section. The result is a simultaneous display of the two inputs.

Fig. 5 - Conventional scope (A) displays both signal and

hum, while a differential scope (B) displays only signal across the load resistor.

Under certain conditions, a dual-trace scope can provide some of the benefits

of a differential amplifier scope. For instance, if there is an A - B mode and the

amplifiers are well matched, the difference of the two inputs is displayed. The

scope manufacturer's operation manual will explain this function where applicable.

Making Differential Measurements. Let's see how differential

scope measurements are made for ungrounded tests. In the circuit shown in Fig. 4,

we want to measure the signal across load resistor RL1. Only the high

signal leads are connected to the circuit under test (at points X and Y). The shields

are connected together and grounded; but they are not grounded at the tips. This

connection reduces the impedance of the loop formed by the shields and equalizes

the currents through the loop, thereby allowing the differential amplifiers to nullify

loop current effects by common mode rejection.

It is not correct to tie both shields together at the probe end and also connect

them to the chassis. This makes a circuit for ground currents through the shield

and can create measurement errors because of voltage difference at the scope. It

would also be wrong to leave both shields unconnected at the probe ends. This would

permit the shields to act like antennas to pick up noise.

The probe tips represent a high impedance to the circuit being tested and do

not introduce excessive loading as did the conventional test circuits shown in Figs.

1 and 2. Since the scope chassis is not tied to a signal high point, there is no

ac line noise introduced.

Reject Common Mode Signals. One of the more important uses of

a differential measurement is to reduce the effects of a common mode signal such

as hum. Common mode signals are identical with respect to amplitude and time. Since

the output of a differential amplifier is the difference between its two inputs,

a common (identical) signal on each input will be reduced (but not eliminated) in

the output. There is a limit as to just how effective a differential amplifier can

be. Its ability to reject common mode signals is known as common mode rejection.

The ratio of the common mode input signal amplitude to the amplitude of the difference

signal displayed on the scope is known as the common mode rejection ratio. The higher

the ratio, the better the differential amplifier.

Fig. 6 - (A) Signal with hum; (B) hum alone; (C) signal

with hum rejected.

For example, if the common mode signal on both inputs is 10 volts and the signal

produces a scope display of only 0.01 volt, the common mode rejection ratio is 10/0.01

or 1000.

Note what happens with a conventional scope measurement as shown in Fig. 5A.

There is an unwanted 60-Hz hum signal in the circuit along with the desired signal.

Assume the hum is 10 volts and the square wave source is 1 volt, of which, 0.6 volt

appears across the component being tested. With the conventional scope setup, both

the 0.6-volt signal and the 10-volt hum would be displayed, as in Fig. 6A.

The desired signal rides on the bothersome hum, making the measurement difficult.

But notice what occurs when a differential scope is used as in Fig. 5B.

In test probe A, is the combined signal and hum; while the hum alone is in probe

B. The scope displays A minus B or only the desired signal across the resistor as

shown in Fig. 6C. The amount of hum that is rejected depends on the scope's

common mode rejection ratio; and if the latter is good, the resultant signal would

have negligible hum.

As we have pointed out, the A - B mode of a dual-trace scope can be used for

differential measurements. The common mode rejection of such a scope, however, is

less than that for a differential amplifier scope. Nevertheless, the ability to

reduce common mode signals to even a small degree would be all that is needed for

making a good measurement.

Posted February 7, 2018

|