January 1957 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Most visitors to RF Cafe

are either engineers, technicians, or hobbyists who deal with watts in terms of

electrical power. This article from the January 1957 edition of Popular Electronics

magazine deals primarily with watts in terms of acoustic power, but it also addresses

how obtaining acoustic watts relates to electrical watts. Audiophiles will appreciate

the table of speaker watts needed based on your room volume as well as rules of

thumb for selecting the amplifier power required to deliver that sound effectively.

You will note that back in the day the common abbreviation for decibels was all

lower case (db) ad opposed to how we do it today (dB). A tech-related comic was

on a page in the article so I included it as well.

The Whys and Wherefores of Watts

By Leonard Feldman By Leonard Feldman

Stop scratching your head over which amplifier to get; here's the answer

to your power output requirements

"Leading authorities maintain that the minimum acceptable power-handling capacity

of a hi-fi amplifier shall be at least 25 watts."

"Our research shows that the purchase of an amplifier having a power rating of

over 10 watts is a waste of money."

"A leading speaker manufacturer has recommended that power amplifiers for use

with his speaker should be rated at 30 watts or better."

"Five watts of audio fed to an 'efficient' loudspeaker is more than the human

ear can stand."

If you're trying to decide which high-fidelity amplifier to buy, you've probably

run across conflicting comments like those above. But before you can hope to find

the amplifier that best suits your needs, you should know what this "power" and

"watts" talk is all about.

All the sound we hear, whether natural or reproduced, is caused by a movement

of air. High-pitched sounds mean that the air is vibrating at a fast rate. Low-pitched

sounds are caused by air moving at a slower rate. It takes power to move this air,

just as surely as it takes power to move an automobile. The more power you apply

to the driveshaft of a car, the faster it will accelerate. Similarly, the harder

you push the air in making sound, the louder will be the sensation to the listener.

DBs and Power. The decibel or "db" is used as a measure of sound

and power because it indicates the way our ears behave when subjected to sound vibrations,

or moving air. When you double the power applied to move the air in making a given

sound, the sound doesn't seem twice as loud, but only slightly louder. We call this

a change of 3 db. On the other hand, 10 db represents a power change of 10 to 1.

In other words, actual power change, measured in watts, (just like the light-giving

power of an electric lamp), is much greater than the equivalent change in decibels.

The decibel method of measurement more nearly approximates the way our hearing system

responds to changes in sound intensity.

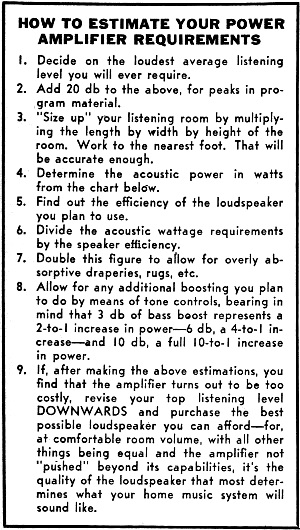

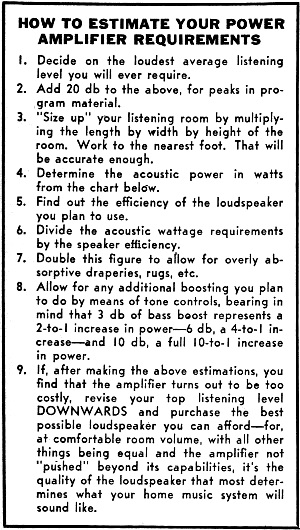

How to estimate your power amplifier requirements.

Table above shows acoustic wattage required for various listening

levels in different-sized rooms. This table, used in conjunction with instructions

listed above, will help you choose correct amplifier for your hi-fi.

Boosting bass, even slightly, may require double the power-handling

capacity of the amplifier. This little known -but important - fact should be considered

when you choose an amplifier for a hi-fi system.

Efficiency of loudspeaker is factor in determining power rating

of amplifier to be used.

It's obvious that the more power an amplifier can feed to a loudspeaker, the

louder is the sound that can be produced by the loudspeaker. However, because of

the way we hear sound, doubling the power of an amplifier will not make its maximum

sound output seem twice as loud, but only slightly louder. To choose an amplifier

suitable to the needs of the listening room, we need to consider several factors:

1. How much power is there behind real live music?

2. How loudly would you like music played in your living room?

3. How loudly will other members of your family let you play music? (The second

and third questions are usually separated by about 10 db!)

4. What speaker are you planning to use with the system?

5. Will you ever want to add additional speakers in other rooms? (Don't answer

this one too hastily!)

6. How large is your listening area and how is it furnished?

Listening Power. Before we even tackle the first question, there's

an important point that needs clearing up. The top rating of an amplifier does not

necessarily indicate how it will sound at lower levels. Take a good-quality 20-watt

amplifier and place it alongside a 10-watt amplifier. Send in just enough signal

to develop, say, 1/2 watt-and it is unlikely that you will hear any difference between

the two. The difference only shows when a very loud sound of 15-watts power must

be fed to the speaker. That's when the first amplifier will handle it, but the second

one will overload and cause annoying distortion.

A good analogy is that of a 100- and a 200-horsepower automobile creeping along

in metropolitan traffic. Since neither car can be "opened up" to its full power,

both travel neck and neck, performing equally well.

HOW TO ESTIMATE YOUR POWER AMPLIFIER REQUIREMENTS

1. Decide on the loudest average listening level you will ever

require.

2. Add 20 db to the above, for peaks in program material.

3. "Size up" your listening room by multiplying the length

by width by height of the room. Work to the nearest foot. That will be accurate

enough.

4. Determine the acoustic power in watts from the chart below.

5. Find out the efficiency of the loudspeaker you plan to use.

6. Divide the acoustic wattage requirements by the speaker

efficiency.

7. Double this figure to allow for overly absorptive draperies,

rugs, etc.

8. Allow for any additional boosting you plan to do by means

of tone controls, bearing in mind that 3 db of bass boost represents a 2-to-1 increase

in power - 6 db, a 4-to-1 increase - and 10 db, a full 10-to-1 increase in power.

9. If, after making the above estimations, you find that the

amplifier turns out to be too costly, revise your top listening level DOWNWARDS

and purchase the best possible loudspeaker you can afford - for, at comfortable

room volume, with all other things being equal and the amplifier not "pushed" beyond

its capabilities, it's the quality of the loudspeaker that most determines what

your home music system will sound like.

How Loud Is Music? The "quietest" sound anyone can hear is measured

at "0 db." The loudest sound anyone can hear before it actually becomes harmful

is about, 120 db louder than the softest sound. Anything we call "sound" - including

music - falls somewhere in between those two extremes.

To get a good idea of where a symphony orchestra playing about 20 feet from you

fits into this picture, refer to the sound level graph on page 49. At first glance,

it would appear that a level of about 80 db is the loudest sound you can expect

to hear. However, bear in mind that these are average levels, and that instantaneous

peaks or bursts of music may actually exceed this particular level by as much as

20 db. (Notice the curve for the bass drum solo, for example.)

Now, if we had a simple way of relating watts of amplifier power to decibels,

we would know how much power would be needed for the amplifier. But - we have to

consider the second and third factors.

Home vs. Concert Hall. Since the purpose of an amplifier and

speaker system is to "push some air around," the question naturally arises, "How

much air?" Even traveling at the same speed, a motor scooter could never haul the

load of a two-ton truck. Similarly, a little one-watt amplifier might make a lot

of noise come out of a loudspeaker (if both you and the speaker are in a coat closet),

but you'd hardly even hear such a system if it were installed in Carnegie Hall.

The truth is, when playing records, you're not in Carnegie Hall but in your living

room. So we've got to determine just how much air has to be pushed around in that

room and how hard it must be pushed to satisfy your musical tastes.

All of this is not meant to imply that you can't duplicate the concert hall level

of 80 db or even 100 db in your living room. All we're saying is that you will most

likely settle for a comfortable 60 db with the possibility of occasional 80-db peaks.

In any case, that's something you must decide for yourself. Having made up your

mind whether to go for full concert hall volume or not, and knowing the size of

your listening area, you can determine from the table on page 50 just how many acoustic

watts of power you'll need to fill the room with that much sound.

Let's work out a sample based on an average living room which measures 12' x

20' and has an 8'2" ceiling. The volume of such a room is just under 2000 cubic

feet (width x height x depth). Suppose, despite our warnings, you decide that at

some time you will want to "crank the system wide open" and really duplicate concert

hall volume, or go for a glorious 80 db on average music, with possible 100-db peaks

on the cymbal crashes. Consulting the chart, you find that you need a mere .31 acoustic

watt (less than 1/3 watt) to do the job. Seems hardly necessary to invest in a power

amplifier at all, does it? Actually, we've been neglecting the biggest unknown of

all, the loudspeaker.

Loudspeaker Efficiency. All along we've

peen talking about acoustic power needed to do the job of making music for our ears.

That means actual power caused by the "back and forth" motion of the loudspeaker

cone itself. There isn't a speaker manufacturer we know of who will deny that by

far the most inefficient of all the components in a hi-fi setup is the loud-speaker

itself. That doesn't mean it's the most inferior part of the system but it does

mean that the speaker puts out far fewer acoustic or usable watts than are put into

it by the power amplifier. Actually, most of the power an amplifier feeds to a loud-speaker

"goes up in heat." (In much the same way, an electric light bulb only converts a

small fraction of the electrical "watts" fed to it from the socket into usable light.

The rest is wasted in the form of heat - a fact easily checked by touching a bulb

that has been lit for several hours!) Loudspeaker Efficiency. All along we've

peen talking about acoustic power needed to do the job of making music for our ears.

That means actual power caused by the "back and forth" motion of the loudspeaker

cone itself. There isn't a speaker manufacturer we know of who will deny that by

far the most inefficient of all the components in a hi-fi setup is the loud-speaker

itself. That doesn't mean it's the most inferior part of the system but it does

mean that the speaker puts out far fewer acoustic or usable watts than are put into

it by the power amplifier. Actually, most of the power an amplifier feeds to a loud-speaker

"goes up in heat." (In much the same way, an electric light bulb only converts a

small fraction of the electrical "watts" fed to it from the socket into usable light.

The rest is wasted in the form of heat - a fact easily checked by touching a bulb

that has been lit for several hours!)

Furthermore, not all loudspeakers have the same efficiency. They vary from "highly

efficient" units of 10% to 20% to all-time lows of considerably less than 1%. If

you've been following the latest advertisements put out by loudspeaker manufacturers,

you probably realize that there's something of a "factional war" going on between

the proponents of the "high" efficiency units and the relatively "low" efficiency

units. Far be it from us to get into the squabble. All we want to do is point out

the fact that a speaker having an efficiency of 1% will require 100 times as much

amplifier power for a given acoustic power - or that, in our example, to get 0.31

acoustic watt means hooking up such a speaker to an amplifier able to supply 31

watts to the speaker. A speaker having an efficiency of 10% will need 10 times as

many amplifier watts for a given number of acoustic watts or, again using our example,

3.2 watts supplied by the amplifier are all that will be needed to meet the same

acoustic requirements.

It should now be apparent that unless you have a fairly good idea of the efficiency

of the loudspeaker you propose to buy, you cannot even attempt to estimate your

amplifier requirements with any reasonable degree of accuracy. This is the single

factor. that we can't put a number on. Only the speaker manufacturer involved can

do that for you - and more and more of them, realizing the misunderstanding that

exists on this one point, are becoming less and less reluctant to publish this information

as a regular part of their sales specifications. It's really nothing to be ashamed

of! Most of us have known for years that an automobile engine only converts about

6% of the energy contained in a gallon of gas into usable power, but we still buy

millions of cars each year!

Multiple Speaker Systems. If you feel that eventually a second

or even a third loudspeaker installation in another room or two is good future planning,

the formula is simple as can be. If the second room is about like the first and

you ever plan to have both speakers going at the same time, you'll need double the

power of your first calculations.

Important point: many loudspeaker installations are equipped with so-called level

controls, or pads, with which it is possible to turn off the sound coming from a

given speaker. Just because the sound is turned off in this manner doesn't mean

you're using less power. The same amount of power is being absorbed at the speaker

terminals. I It's simply all used up as heat in the wire-wound resistor which makes

up the speaker-control. The only way an amplifier can be used for two speakers and

still require the power calculated for only one is if you actually switch the appropriate

speaker in and out, effectively disconnecting one terminal of each speaker not in

use.

Tone Controls Use Power. If your listening room, your personal

tastes, or any of countless other factors make you want to add a little bass boost

by means of the tone controls on your amplifier, you'd better take that fact into

account before you go shopping for watts. Remember, a bass boost of only 3 db requires

double the power-handling capacity at certain frequencies than would be the case

if all your tone controls were set for flat response!

Power and Frequency Response. As long as we're talking about

specifications, there's one the amplifier people could be a little more detailed

about. Amplifiers, as a rule, perform best for "middle" tones. The extremely low-pitched

and high-pitched tones are generally much harder to reproduce at high power levels.

An orchestra,

however, has instruments at both extremes as well as in the "middle", and you'll

notice from our graph that all the frequencies need pretty much the same power for

a given volume of sound. Therefore, it's important to know not just that a given

amplifier produces a maximum undistorted power of "5 watts" or "10 watts" or even

"50 watts," but that it can produce that much power at all the frequencies involved

in musical reproduction, or at least from 30 cps to 15,000 cps. If this were not

the case, certain instruments would be clear and undistorted at maximum volume while

others, such as the bass drum or cymbals, might be annoyingly distorted at the same

listening level.

The important thing to remember when choosing an amplifier is that a high-fidelity

system has to work properly as a whole, and that the loudspeaker, listening room,

and personal listening preferences must be carefully considered before you can pin

a number on the amount of watts required. The right amount of watts, however, can

really "make" a hi-fi system.

Posted April 26, 2023

(updated from original post

on 3/6/2013)

|

Loudspeaker Efficiency. All along we've

peen talking about acoustic power needed to do the job of making music for our ears.

That means actual power caused by the "back and forth" motion of the loudspeaker

cone itself. There isn't a speaker manufacturer we know of who will deny that by

far the most inefficient of all the components in a hi-fi setup is the loud-speaker

itself. That doesn't mean it's the most inferior part of the system but it does

mean that the speaker puts out far fewer acoustic or usable watts than are put into

it by the power amplifier. Actually, most of the power an amplifier feeds to a loud-speaker

"goes up in heat." (In much the same way, an electric light bulb only converts a

small fraction of the electrical "watts" fed to it from the socket into usable light.

The rest is wasted in the form of heat - a fact easily checked by touching a bulb

that has been lit for several hours!)

Loudspeaker Efficiency. All along we've

peen talking about acoustic power needed to do the job of making music for our ears.

That means actual power caused by the "back and forth" motion of the loudspeaker

cone itself. There isn't a speaker manufacturer we know of who will deny that by

far the most inefficient of all the components in a hi-fi setup is the loud-speaker

itself. That doesn't mean it's the most inferior part of the system but it does

mean that the speaker puts out far fewer acoustic or usable watts than are put into

it by the power amplifier. Actually, most of the power an amplifier feeds to a loud-speaker

"goes up in heat." (In much the same way, an electric light bulb only converts a

small fraction of the electrical "watts" fed to it from the socket into usable light.

The rest is wasted in the form of heat - a fact easily checked by touching a bulb

that has been lit for several hours!)