|

April 1948 Popular Science

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Popular

Science, published 1872-2021. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Spark-induced interference

(noise) in amplitude modulation (AM) radio has been a problem since the early

days of broadcasting. Whether from a natural source (QRN in Ham lingo) like

lightning or electric eel discharge (just kidding), or from multitudinous

man-made sources (QRM), static manifests itself audibly as a scratching,

crackling sound emanating from a speaker, headphone, or ear bud. I explain this

because probably most people under twenty years old have never heard (or heard

but not recognized) static in audio. Almost nobody under forty years old has

ever seen the static-induced effect on video from a television screen (see photo

in article). A very familiar manifestation of static noise for ICE (internal

combustion engine - aka normal cars) originates in the ignition system. As its

name suggests, the raison d'être of a spark plug is to generate a spark to

ignite the fuel-air mixture in the cylinders. That spark's electromagnetic

signature includes a broadband smear of frequencies, many of which fall within

the bandwidth of a radio's circuitry, in RF, IF, and audio portions. Filtering

it out once inside the radio is virtually impossible, so means are implemented

to suppress it at the source. This 1948 issue of Popular Science

magazine article discusses some of the early attempts at identifying and

mitigating the issue. Frequency modulation (FM) radio eliminated most of the

ignition noise problem, but AM can still present problems. Electric vehicles (EV's)

are reigniting (pun intended) the electrical noise issue due to all the onboard

DC-DC converters and computers. The EV industry's solution, if allowed to move

forward, is to have auto manufacturers

stop providing AM radio in cars.

Unmaking Man-Made Static

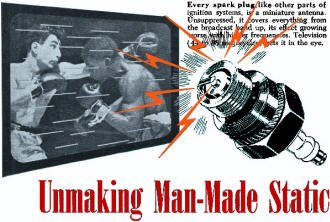

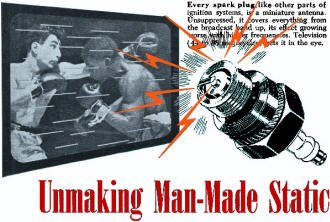

Every spark plug, like other parts of ignition systems, is a

miniature antenna. Unsuppressed, it covers everything from the broadcast band up,

its effect growing worse with higher frequencies. Television (44 to 88 megacycles)

gets it in the eye.

Ignition noise, long a radio nuisance, faces a campaign designed to knock it

out of the television picture.

Automobile ignition systems have been producing spluttery noises in radios since

the days of crystal sets. With television, the noises turned into visible streaks

and blotches - and thereby set the stage for a large-scale attack on one of radio's

oldest minor headaches.

The attack began during the war, when ignition interference was a major threat

to vital military communications. To clear the air, a fleet of mobile Signal Corps

test stations toured the country, teaching manufacturers how to build ignition systems

that wouldn't sound off through near-by radios.

Static is fundamentally just like any amplitude-modulated (AM) radio signal.

Frequency modulation will reject it, but short of using FM for every purpose, the

only way to keep interference out of a radio completely is to suppress it at the

source.

Eliminating ignition interference is a relatively simple operation, done quickly

and easily on any car that carries its own radio. Resistors in spark-plug cables

keep electro-magnetic impulses from feeding back into the wiring, which would broadcast

them; metal shielding around cables and other parts helps trap other impulses, and

capacitors channel them to the chassis, which is bonded into a nonbroadcasting ground.

|

Three steps in Signal Corps' program show progress

from separate resistor-suppressor cap (on left) through bulky external shield (center),

to specially designed, waterproof spark plug with built-in shield and suppressor

(right).

Full shielding on plugs and cables of an Army

truck illustrates care necessary to block interference at extremely high frequencies.

Distributor and coil are also shielded; chassis parts are bonded together; generator

and voltage regulator are grounded through capacitors.

|

A radio-noise detector, this compact test set

was developed to check suppression devices on equipment purchased by the Army. Measuring

impulse noise from 0.15 to 40 megacycles, it will also enable repair depots to spot

and eliminate interference from older-type equipment.

Plugs that suppress themselves are now ready

for U.S. motorists. Resistor, indicated by pencil point, seals in noisy impulses.

According to manufacturers, it also lengthens plug's life and improves its performance.

|

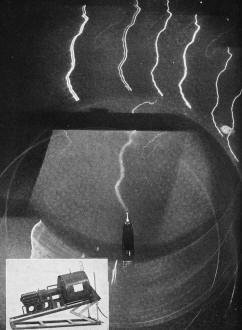

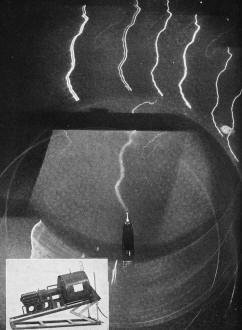

Microsecond technique splits a lightning flash.

GE's special camera (inset) shows that bolt striking Empire State Building (center

of photo) is one slow discharge and six fast ones.

Experts at the Coles Signal Laboratory, at Fort Monmouth, N. J., figured out

scores of variations on that basic pattern. Early systems with bulky external shields

barred interference only up to 40 megacycles. Research has now progressed to simpler,

integrally shielded and suppressed equipment that promises interference-free communications

clear up to 4,000 megacycles - and also makes ignition systems waterproof.

By putting the program on a mass-production basis, military experts hurdled the

biggest barrier to getting rid of ignition static - the fact that thirty-odd million

U. S. cars have to be "suppressed."

Now the American auto industry has taken over, and cars are being built to a

set of anti-interference standards worked out by radio makers and the Society of

Automotive Engineers. Accessory makers are also providing war-developed devices

to help the program.

As millions of prewar cars go off to junkyards, radio reception will be freed

of one source of man-made static. Short-wave operators will say good-by to a lot

of the "garbage" that has plagued them for years. And owners of television sets

won't have to fight shy of highways or set up sky-high antennas to avoid spots before

their eyes.

Posted January 3, 2024

|