|

July 1949 Popular Science

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Popular

Science, published 1872-2021. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

In 1949 Westinghouse

revealed the first U.S. nuclear-reactor built to drive a propeller (on a

submarine - airplanes would come later, supposedly), to be tested at the AEC's

Idaho "Reactor Farm." This 1949 Popular Science magazine article

explains fission using word pictures: a single extra neutron cracks a heavy

uranium-235 nucleus into two smaller, neutron-bloated fragments (actual modern

alchemy);

these "delayed" neutrons emerge slowly, giving time to insert control rods made

of neutron-absorbing material - like a "spoon in the cup" damping a coffee slosh

- so heat is produced continuously yet safely. The excess neutrons also trigger

a second trick: "breeders" capture them in a blanket of ordinary uranium,

coaxing it to produce fresh plutonium as the reactor generates power. In short,

the piece deftly shows how the Idaho prototype teaches sailors to master fission

as a controllable, ship-worthy fire and as a factory that makes more fuel than

it burns.

Will Atomic Engines be Mobile?

PS Model by Herbert Pfister

This model shows arrangement Dr. Clark Goodman discusses in new nuclear-power

textbook.

Atomic engine would increase the range of a submarine and enable it to be submerged

longer.

Navy will get experimental model. Delayed neutrons will make it safe and easy

to run.

By Volta Torrey

PS photos by Hubert Luckett

Westinghouse engineers are preparing now to assemble the U. S. Navy's first atomic

engine. It will be the first nuclear reactor designed to turn a propeller.

This one, its sponsors say, will never go to sea or take an airplane off a runway.

It is to be permanently based on the Atomic Energy Commission's new Reactor Farm

in Idaho, 600 miles from the ocean. But some day this reactor may be as highly valued

an historic treasure as the Wright brothers' first airplane - because it is expected

to be the prototype of many propulsion units that will be run with fissionable atoms

just like those now put into bombs.

Engines of this type may add tens of thousands of miles to the cruising ranges

of ships. Running such engines, moreover, will be quite simple, and blowing one

tip will be extremely difficult - yet each one will have to be imprisoned like a

criminal.

Heavy walls will surround this engine because those strange little things that

the physicists call neutrons are to be used in it, to split atoms, to produce heat,

to turn a shaft. Having too many neutrons at large is so unhealthy that they must

be firmly confined - but their somewhat-human traits tend to make them very obliging

prisoners.

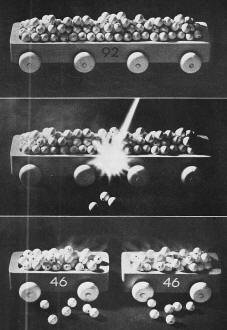

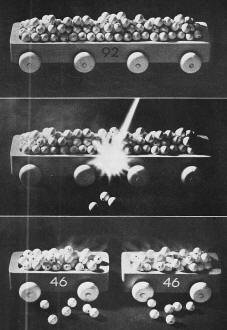

Atomic nuclei are vehicles for neutrons. A nucleus

with 92 protons can retain 143 neutrons, as in cart at top. Splitting the nucleus

with another neutron, as in center picture, knocks a few neutrons out, but leaves

the two nuclei that are then formed overloaded with neutrons. A nucleus with only

46 protons cannot permanently retain more than 64 neutrons, so some are tossed out

belatedly by many over-loaded nuclei. Delayed arrival of those neutrons makes it

easy to control the rate at which the temperature of a reactor rises.

Some neutrons are always late for work, and when given a chance nearly all of

them quickly desert the chain gangs into which men put them. This is what makes

it easy to slow down an engine in which they are the firemen.

But even while some neutrons are working diligently, others are sure to cause

trouble. Atoms become pregnant because of neutrons, and have children and grandchildren.

The neutrons, meanwhile, change their identities and disappear. This mischief is

responsible for what you and I call radioactivity-and too much of that, as you know,

is not good for human beings.

These are some of the facts that reactor builders must ponder.

For the Next 18 Months

The AEC plans to build only four reactors during the next year and a half. Two

will be breeders, intended to produce more nuclear fuel as well as power (PS, June

'49, p. 124), and one will be a special type designed to test the metals, ceramics,

and liquids that the engineers would like to use in future models. The fourth reactor

- and the only one designed to produce a specific amount of power for a specific

purpose - will be the Navy's propulsion unit.

Plans for this mobile type will be completed in a new, 600-man Westinghouse laboratory

near Pittsburgh. Before it is put together, construction of the materials-tester

will be under way in Idaho, and by the time it is finished more will be known about

what must be done in order to put similar nuclear engines into ships, planes, and

rockets.

Neutrons Depend on Partners

The engineers believe now that a shielded atomic engine, very little heavier

than the engines, burners, and tons of oil now carried by some naval vessels, can

be developed fairly soon. Later, it may be possible to make one light enough for

huge aircraft. But mountains of work remain to be done because of the neutrons'

peculiarities.

No way is yet known of extracting great and useful amounts of energy from the

nuclei of atoms without the help of neutrons. They are the heaviest things in atoms,

and they stick together tightly in nuclei. To do this, however, they need partners.

Those partners are protons.

The number of protons in an atom limits the number of neutrons that can remain

forever in its nucleus. A lot of protons can bind an even larger number of neutrons

together. But when the number of protons is reduced, the number of neutrons that

can stay in a nucleus with them is often reduced considerably more.

An atom of Uranium 235, for example, has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. But an

atom with only half that many protons (46) cannot permanently accommodate more than

64 neutrons, which is less than half (71.5) of the number of neutrons in the uranium

atom.

A nucleus that is overloaded with neutrons behaves, at first, like any other

kind of overloaded machine or man. Instead of collapsing instantly, it usually wobbles

along for a while. Nevertheless, sooner or later, the machine must be strengthened

or some of the load must be removed.

To show your friends how a nuclear reactor is

controlled, surround a coffee cup with sponges to represent shielding and insert

another sponge to represent control rods. Drawing the rods out permits the reactor

to start. Shoving them back in retards it because they "absorb" neutrons.

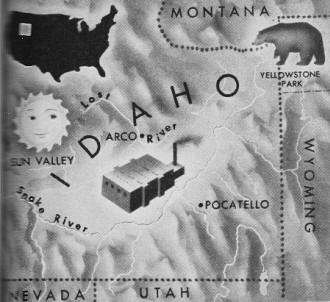

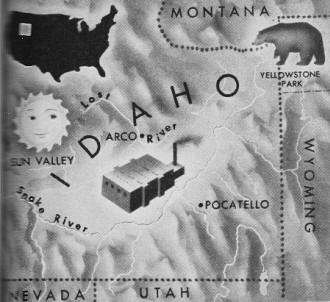

New reactor station in Snake River Valley of

Idaho will cover 625 square miles. A materials-tester and a propulsion unit for

the Navy will be first two reactors built there. Eventually, many more experimental

atomic engines may be tried out in this scenic area of the Rockies.

Wobbling Explains Radioactivity

Physicists call atoms that contain too many neutrons "unstable." This instability,

or tendency to wobble, makes them radioactive. And that is simply a scientific way

of saying that something is sure to happen to them.

An unstable nucleus may strengthen itself by giving birth to a meson - one of

the marvelous things that scientists are now studying very intently. Within the

nucleus, this meson may turn into a different kind of meson, which may give birth

to an electron. And if you were to examine an atom after such changes inside of

it, you would find that it had become an atom of a different element, because an

additional proton would have appeared in it, and one of its neutrons would have

vanished.

But, as you might well imagine, having a child and a grandchild takes time -

and - a wobbly, overloaded nucleus often can stabilize itself more simply by throwing

off part of its neutron burden. Several kinds of radioactive atoms just heave a

neutron out when they are overloaded.

The neutrons that are tossed out intact but tardily by the new atoms created

when atoms of Uranium 235 are split are politely referred to by reactor experts

as "delayed" neutrons. They tend to make nuclear reactors sluggish and, consequently,

are extremely helpful, because the sluggishness of reactors makes it quite easy

for men to control them.

What Will Be Cooking

If you could look into the boiler of the engine now being designed for the Navy,

and see with the help of some impossibly powerful microscope what the physicists

say will happen in it, you would see hordes of free neutrons splitting enormous

numbers of atoms of Uranium 235. The free neutrons would virtually never break one

of those atoms into two equal halves. Instead, they would break the big atoms into

smaller atoms of tin, antimony, arsenic, zinc, and about two dozen other elements-but

nearly all of those new atoms would be overburdened with neutrons. If one was not,

the other one that had come out of the same uranium atom would be very seriously

overloaded.

Those new atoms would contain too many neutrons because only a few of each uranium

atom's 143 neutrons would have been knocked out when the big atom was split. Most

of its neutrons would cling with the protons in the nuclei of the newly" formed

lighter atoms. But the protons of those new atoms would not be able to hold so many

hangers-on together forever, and in the course of time quite a few of them would

be thrown out.

If you could focus your imaginary super-super-microscope on a single atom's nucleus,

you might find that it was an overloaded and shaking bit of bromine - an element

familiar to chemists as a reddish-brown, evil-smelling liquid. By having meson descendants

within its nucleus, this atom might turn a neutron into a proton, and become an

atom of krypton, which is one of the rare gases in the atmosphere.

But, if you looked very, very closely, you might find that this krypton atom

was unstable, too. If it went on having children and grandchildren, it eventually

would become an atom of rubidium, a soft, silvery-white metal.

That excited krypton atom, however, might practice birth control and stabilize

itself by simply hurling out one of the neutrons responsible for its agitation.

No one has ever seen a krypton atom do this, and no one ever will. But the physicists

can prove that, whenever a great many atoms of Uranium 235 are split, neutrons will

emerge tardily from several kinds of radioactive fragments such as that krypton

atom.

They even know, in fact, how many neutrons can be counted on to be unavoidably

delayed: one percent of all the neutrons freed will not appear until a hundredth

of a second or more after the Uranium 235 atoms have come apart. A substantial number

of them will be about eight seconds late, and some will be a whole minute behind

time.

The Dragon at Los Alamos

Ingenious and daring experiments were performed to find this out. Prof. O. R.

Frisch and his assistants at Los Alamos almost produced a bomb, momentarily, in

a device that they called the Dragon. In it, a slug of Uranium 235 was allowed to

fall through a hole in a larger chunk of the same material resting on a table.

While the slug was going through that hole, millions of neutrons popped out and

broke a great many Uranium 235 atoms. But the slug passed on, through a hole in

the table into a box beneath the table, before enough neutrons had gotten out of

the fission fragments to split enough more atoms to cause trouble. F. de Hoffman,

B. T. Field, and B. R. Stein examined this slug, found that neutrons still were

coming out of it, and counted them.

The tardiness of such neutrons made it difficult to design a bomb, but comparatively

easy to design controllable reactors. None of the latter has exploded, because the

delayed arrival of some of the neutrons always gives the operators of such reactors

- and the electrical devices that aid them - ample time in which to act whenever

things start to happen too fast.

The Spoon in the Cup

The "neutron flux" in a controllable reactor is regulated very simply. If you

have eaten frequently in railroad dining cars, you probably have learned to reduce

the danger that your coffee will be spilled by leaving your spoon in the cup. The

spoon retards the rate at which the waves in the liquid can grow higher and thus

become big enough to pass over the cup's rim. Something better than a spoon, however,

can be left in a nuclear reactor.

There are materials that absorb neutrons as readily and even more quickly than

sponges absorb water. Rods made out of those materials are run through the reactors.

They make it possible to control the rate at which the number of neutrons at work

rises, and thus regulate the temperature of the reactor.

To start the Navy's atomic engine, some of those rods will be drawn out. To allow

more neutrons to split more atoms, another rod will be partially withdrawn. And

to slow the reactor down, by reducing the number of neutrons on the job, one or

more of the rods will be shoved back in far enough to absorb as many of them as

necessary. Those rods may even be adjusted automatically by devices comparable to

the thermostats that regulate ordinary furnaces in many homes.

"To keep a pile running at a steady rate," says Enrico Fermi, who built and ran

the first one beneath a stadium in Chicago, "is an art that can be mastered in a

few hours." Hence, every man in the crew of an atomic-powered ship may learn to

apply the brake.

But might not an enemy's bomb or shell cause an atom,ic reactor to blow up?

This would be highly improbable because ( 1) the same shielding that would protect

the crew from radioactivity could serve as armor to protect the atomic boiler, and

(2) that boiler could be so designed that loss of control of its temperature would

result only in a big fizzle. It could, in fact, be made less liable to blow up than

other parts of a ship.

Although uranium has been mined for eight centuries, and used to color crocks,

imitation jewels, and the caution lights in traffic signals, there is no record

of it ever having exploded except under conditions that are hard to bring about.

Why Reactors Are Big

Puncturing the casing of a controllable atomic boiler would let neutrons escape

and tend to reduce the rate at which it produced heat. But those neutrons, and the

other radiation that would zoom out with them from the unstable atoms in the reactor,

might be very harmful to people.

The shielding that protects people is what makes most controllable reactors big

and cumbersome. Ways to reduce its weight may be found with the help of the specially

designed materials-tester soon to be built.

A second reason for the immensity of some reactors is that they are run with

uranium that contains only a small percentage of fissionable atoms. But the Navy

reactor is to be run with fuel that has been "enriched" with such atoms. Hence,

its boiler may be quite small.

In this respect, it will be a sister of the two smallest reactors now running.

Both are at Los Alamos. One is called the Water Boiler because its fuel is fed to

it in liquid form. The other is called Clementine, because its diet is Plutonium

239, for which the wartime code name was "Forty-niner."

Atomic Submarine First

The Navy engine's fuel tank - which will also be its boiler-will have to be taken

out periodically so that the fragments of broken atoms can be removed, and fresh,

fissionable atoms inserted. But the tank will not be noticeably lighter when its

contents have been used up than when they are fresh because, despite the tremendous

amounts of heat that this fuel yields, only a tiny fraction of its weight will be

converted into energy.

The first actual installation of such an engine, many engineers believe, is likely

to be in a submarine. There it would be especially advantageous because nuclear

fuel can be consumed without oxygen. In a submarine, moreover, tons of batteries

and fuel might be found to be unnecessary.

Suppose that such submarines, roaming the seven seas, and remaining submerged

as long as their crews were willing, also were equipped to plant atomic mines or

flip atomic projectiles into areas like Pearl Harbor ...

Suppose, too, that men continue to make the planes that carry bombs bigger, and

nuclear reactors smaller ...

These grim thoughts are not ridiculous. Millions of dollars, from your pockets

and mine, are being spent to make developments of this sort possible - and the only

alternative is to persuade the leaders of other nations that atomic energy must

be controlled internationally.

|