June 1944 QST

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

QST, published December 1915 - present (visit ARRL

for info). All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Recognizing that many people were reluctant

to approach the theoretical aspect of electronics as it applied to circuit design

and analysis, QST (the American Radio Relay League's monthly publication)

included equations and explanations in many of their project building articles.

Occasionally, an article would be published that dealt specifically with how to

use simple mathematics. In this case, the June 1944 edition, we have the second

installation of at least a four-part tutorial that covers resistance and reactance,

amplifier biasing (tubes since the Shockley-Bardeen-Brattain trio hadn't invented

the transistor yet) oscillators, feedback circuits, etc. I do not have Part I

from the

May 1944

edition or Part IV from the

August

1944 edition, but if you want to send me those editions, I'll be glad to scan

and post them (see

Part

III here).

Practical Applications of Simple Math: Part II - Plate and Screen

Voltages

By Edward M. Noll, EX-W3FQJ

Whenever the d.c. plate current flows through any resistance placed in the plate

circuit of a vacuum tube as a load or coupling medium, it is obvious that the voltage

at the plate will be less than the supply voltage because of the voltage drop across

the resistance.

In Fig. 1 the plate voltage is

Ep = Eb - RpIp.

Example: In Fig. 1,

Eb = 250 volts. Rp = 10,000 ohms.

Ip = 10 ma. (0.01 amp.).

What is the plate voltage, Ep?

Ep = 250 - (10,000) (0.01) = 250 - 100 = 150 volts.

Since true plate voltage is the voltage between plate and cathode, the voltage

drop across the cathode resistor, Rk in Fig. 2, as well as the drop

across the plate resistor, Rp, must be subtracted from the supply voltage

in calculating plate voltage.

In Fig. 2 the plate voltage is In Fig. 2 the plate voltage is

Ep = Eb - IpRp- IpRk.

= Eb - Ip(Rp + Rk).

Example: In Fig. 2,

Eb = 250 volts.

Rp = 25,000 ohms.

Rk = 2000 ohms.

Ip = 5 ma. (0.005 amp.).

What is the plate voltage, Ep?

Ep = 250 - (0. 005) (25,000 + 2000)

= 250 - (0.005) (27,000) = 250 - 135

= 115 volts.

One advantage of transformer coupling between audio-amplifier stages is that

the inductance of the transformer primary winding will provide a high-impedance

load for the tube at audio frequencies, while the d.c. resistance of the winding

is sufficiently low to cause only a small drop in d.c. plate voltage.

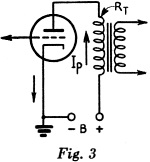

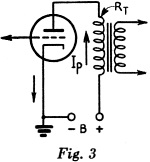

In Fig. 3 the only resistance affecting

the plate voltage is that of the transformer primary winding, Rt, so In Fig. 3 the only resistance affecting

the plate voltage is that of the transformer primary winding, Rt, so

Ep = Eb - IpRt

Example: In Fig. 3,

Ep = 250 volts. Ip = 20 ma. (0.02 amp.)

Rt = 100 ohms.

What is the plate voltage, Ep?

Ep = 250 - (0.02) (100) = 250 - 2

= 248 volts.

Screen voltage is determined in the same manner as plate voltage, using the screen

current to calculate the voltage drop across the screen resistor.

Ep = Eb - IpRp

Es = Eb - IsRs

Example: In Fig. 4, Example: In Fig. 4,

Eb = 250 volts. Ip = 5 ma. (0.005 amp.).

Rp = 20,000 ohms. Is = 2 ma. (0.002 amp.).

Rs = 75,000 ohms.

What are the plate voltage, Ep, and screen voltage, Es?

Ep = 250 - (0.005) (20,000) = 250 - 100 = 150 volts.

Es = 250 - (0.002) (75,000) = 250 - 150 = 100 volts.

In the circuit of Fig. 5, both plate and screen currents flow through the

common resistor, R1, so that plate and screen currents must be added

in calculating the voltage drop across R1.

Ep = Eb - (Ip + Is) (R1)

- IpRp

Es = Eb -" (Ip + Is) (R1)

- IsRs.

Example: In Fig. 5, Example: In Fig. 5,

Eb = 250 volts. Rp = 40,000 ohms.

Rs = 200,000 ohms. Ip = 2 ma, (0.002 amp.)

Is = 0.5ma. (0.0005 amp.). R1 = 20,000 ohms.

What are the plate voltage, Ep, and screen voltage, Es?

Ep = 250 - (0.002 + 0.0005) (20,000) - (0.002) (40,000)

= 250 - 50 - 80

= 120 volts.

Es= 250 - 50- (0. 0005) (200,000)

= 250 - 50 - 100

= 100 volts.

In the circuit of Fig. 6-A, the screen

voltage, Es, is obtained from a tap on a voltage divider consisting of

Rs and Rb The equivalent circuit is shown in Fig. 6-B.

The screen voltage, Es, is equal to the voltage drop across Rb.

Therefore, In the circuit of Fig. 6-A, the screen

voltage, Es, is obtained from a tap on a voltage divider consisting of

Rs and Rb The equivalent circuit is shown in Fig. 6-B.

The screen voltage, Es, is equal to the voltage drop across Rb.

Therefore,

Es = RbIb.

Example: In Fig. 6-B,

Eb = 250. Is = 1 ma. Rs = 10,000 ohms.

Rb = 40,000 ohms.

What is the screen voltage, Es?

Es = IbRb.

Since Eb is equal to the sum of the voltages across Rs

and Rb,

Eb = RsIsr + RbIb.

Also, since both Ib and Is must flow through Rs,

Isr = Ib + Is.

Substituting this value for Isr in the above equation,

Eb = Rs (Ib + Is) + RbIb.

Transposing,

RsIb + RbIb = Eb - RsIs

Ib(Rs + Rb) = Eb - RsIs

Substituting known values,

Then,

Es = (0.0048) (40,000) = 192 volts.

In the circuit of Fig. 7, both screen and

grid-biasing voltages are taken from voltage dividers. In the case of the divider

in the grid circuit, the voltage division is in exact proportion to the resistance

values of the divider sections, since it is assumed that the grid is biased so that

no grid current flows. Therefore, the grid-biasing voltage, Eg, is the

voltage developed across R2 by virtue of the current flowing through

it from the bias supply. In the circuit of Fig. 7, both screen and

grid-biasing voltages are taken from voltage dividers. In the case of the divider

in the grid circuit, the voltage division is in exact proportion to the resistance

values of the divider sections, since it is assumed that the grid is biased so that

no grid current flows. Therefore, the grid-biasing voltage, Eg, is the

voltage developed across R2 by virtue of the current flowing through

it from the bias supply.

Eg = IgR2

being the bias-supply

voltage. being the bias-supply

voltage.

Substituting,

Screen and plate voltages are calculated as before.

Example: In Fig. 7,

Eb = 250 volts. Ec = 100 volts.

R1 = 49,000 ohms.

R2 = 1000 ohms. R3 = 30,000 ohms.

R4 = 20,000 ohms. R5 = 20,000 ohms.

Is = 1 ma. (0.001 amp.).

Ip = 5 ma. (0.005 amp.).

What are the grid-biasing, screen and plate voltages?

Eg =

= 2 volts (negative in respect to cathode).

Ep = 250 - (0.005) (20,000) = 250 - 100

= 1.50 volts.

Es = IbR3

= 0.0046 amp.

Es = (0.0046) (30,000) = 138 volts.

Fig. 8 is used to illustrate the effects

of low voltmeter resistance upon the accuracy of voltage measurements. Rm

is the meter resistance. Fig. 8 is used to illustrate the effects

of low voltmeter resistance upon the accuracy of voltage measurements. Rm

is the meter resistance.

With the meter disconnected, the plate voltage will be

Ep = Eb - RpIp.

However, with the meter connected, the current, Im, will flow through

Rp. Thus, the voltage drop across Rp will increase and the

plate voltage will be lowered, especially when the resistance of the meter is low

in comparison with Rp. The equivalent circuit with the meter connected

is shown in Fig. 8-B, in which Rpi is the internal resistance of

the tube which is assumed to be constant with a change in plate voltage. The new

plate voltage desired is the voltage across Rpi (or Rm) which

is

Ep = Eb - (Ipm) (Rp),

where Ipm is the new current when Rm is connected. In other

words, Ep is the difference between the terminal voltage and the voltage

drop across Rp.

Example: In Fig. 8,

Eb = 250 volts. Ipi =0.1 ma. (0.0001 amp.)

Rp = 1 megohm (1,000,000 ohms)

Rm = 1000 ohms per volt (300-volt scale).

What is the true plate voltage with the meter disconnected and what voltage will

be measured by the meter when it is connected?

Ep = 250 - (1,000,000) (0.0001)

= 250 - 100

= 1.50 volts = plate voltage without meter connected.

As stated above, when the meter is connected,

Ep - Eb - (Ipm) (Rp).

Since Ipm is not known, its value must be found before the equation

can be solved. To find Ipm, the resultant resistance of Rm

and Rpi in parallel must be found, and this, in turn, requires that Rpi

be determined. This can be done by considering the circuit before the meter is connected.

The total circuit resistance, Rt is then given by

= 2,500,000 ohms = 2,500,000 ohms

= 2.5 megohms.

Also,

Rt = Rp + Rpi

Rpi = Rt - Rp = 2,500,000 - 1,000,000

Rpi = 1,500,000 ohms = 1.5 megohms.

The resistance of the meter, Rm, is given as 1000 ohms per volt. Since

the meter has a 300-volt scale, its resistance is 300,000 ohms, or 0.3 megohm.

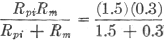

Rpim, the resultant resistance of Rpi and Rm

in parallel is given by

Rpim =

This gives the total circuit resistance in Fig. 8-B as

Rt = Rp + Rpim = 1 + 0.25 + 1.25 megohms.

The new current, Ipm, is then

Ipm =

Then

Ep = Eb - (Ipm) (Rp)

= 250 - (0.0002) (1,000,000)

= 250 - 200 = 50 volts = voltage indicated by meter

reading.

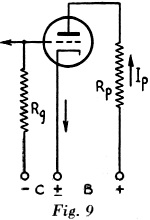

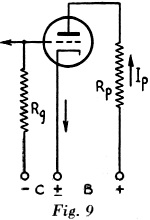

Example: In the case of Fig. 9,

it is assumed that the grid is to be fed a square-wave pulse. Compare the plate

voltage when the tube is conducting a current of 15 ma. with the effective plate

voltage when the tube is idle and not drawing plate current. The plate resistance

is 10,000 ohms. Example: In the case of Fig. 9,

it is assumed that the grid is to be fed a square-wave pulse. Compare the plate

voltage when the tube is conducting a current of 15 ma. with the effective plate

voltage when the tube is idle and not drawing plate current. The plate resistance

is 10,000 ohms.

When the tube is conducting,

Ep = Eb - IpRp ;= 250- (0.015) (10,000)

= 250 - 150 = 100 volts.

When the tube is not conducting, there is no voltage drop across Rp

and the plate voltage is 250, the same as the supply voltage, Eb.

Fig. 10 illustrates another

use for the voltages divider. The coupling circuit shown is that commonly found

in direct-coupled amplifiers. From the equivalent circuit of Fig. 10-B, it

will be seem that the plate of the first tube is connected at one tap on the voltage

divider, while the grid is connected at another tap less positive. It is assumed

that the grid of the second tube is biased, by the voltage drop across its cathode

resistor, so that the grid does not draw current. Fig. 10 illustrates another

use for the voltages divider. The coupling circuit shown is that commonly found

in direct-coupled amplifiers. From the equivalent circuit of Fig. 10-B, it

will be seem that the plate of the first tube is connected at one tap on the voltage

divider, while the grid is connected at another tap less positive. It is assumed

that the grid of the second tube is biased, by the voltage drop across its cathode

resistor, so that the grid does not draw current.

Example: In Fig. 10,

Eb = 250 volts. Ip = 5 ma. (0.005 amp.)

R1 = 10,000 ohms. R2 = 75,000 ohms

R3 = 25,000 ohms.

What are the plate voltage of the first tube, and the grid voltage of the second

tube?

The total drop across all resistors is, of course, equal to the applied voltage,

Eb. The voltage, across R1 is R1I1,

while that across R2 and R3 in series is (R2 +

R3) (I2), bearing in mind that no current is being drawn from

the tap, marked G in Fig. 10-B, so that the same current flows through. R2

and R3. Then,

Eb = R1I1+ (R2 + R3) (I2)

Since both Ip and I2 flow through R1,

I1 = Ip + I2

Substituting this value for I1 in the preceding equation,

Eb = (Ip + I2) (R1) + (R2

+ R3) (I2).

Substituting known values,

250 = (0.005 + I2) (10,000) + (75,000 + 25,000) (I2)

= 10,000I2 + 50 + 100,000I2

110,000I2 = 200

I2= 0.0018 amp. = 1.8 ma.

The plate voltage of the first tube is equal to the sum of the voltage drops

across R2 and R3.

Ep = I2 (R2 + R3) = (0.0018) (100,000)

= 180 volts.

The grid voltage of the second tube is equal, to the voltage drop across R3.

Eg = I2R3= (0.0018) (25,000) = 45 volts.

|

In Fig. 2 the plate voltage is

In Fig. 2 the plate voltage is  In Fig. 3 the only resistance affecting

the plate voltage is that of the transformer primary winding, Rt, so

In Fig. 3 the only resistance affecting

the plate voltage is that of the transformer primary winding, Rt, so

Example: In Fig. 4,

Example: In Fig. 4,

Example: In Fig. 5,

Example: In Fig. 5,

In the circuit of Fig. 7, both screen and

grid-biasing voltages are taken from voltage dividers. In the case of the divider

in the grid circuit, the voltage division is in exact proportion to the resistance

values of the divider sections, since it is assumed that the grid is biased so that

no grid current flows. Therefore, the grid-biasing voltage, Eg, is the

voltage developed across R2 by virtue of the current flowing through

it from the bias supply.

In the circuit of Fig. 7, both screen and

grid-biasing voltages are taken from voltage dividers. In the case of the divider

in the grid circuit, the voltage division is in exact proportion to the resistance

values of the divider sections, since it is assumed that the grid is biased so that

no grid current flows. Therefore, the grid-biasing voltage, Eg, is the

voltage developed across R2 by virtue of the current flowing through

it from the bias supply.  being the bias-supply

voltage.

being the bias-supply

voltage.

= 2,500,000 ohms

= 2,500,000 ohms

Example: In the case of Fig. 9,

it is assumed that the grid is to be fed a square-wave pulse. Compare the plate

voltage when the tube is conducting a current of 15 ma. with the effective plate

voltage when the tube is idle and not drawing plate current. The plate resistance

is 10,000 ohms.

Example: In the case of Fig. 9,

it is assumed that the grid is to be fed a square-wave pulse. Compare the plate

voltage when the tube is conducting a current of 15 ma. with the effective plate

voltage when the tube is idle and not drawing plate current. The plate resistance

is 10,000 ohms.