|

January 1948 Radio-Craft

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Prior to modern flat screen

LED, LCD, and (rarely anymore) plasma television displays, image projection

systems ruled. Cathode ray tubes (CRTs) dominated image displays from around the

1940 through the early 2000s. Prior to that electromechanical projection schemes

were used to basically magnify a small picture and display it on a larger screen

- either from the front or from the back. Some of the gizmos were pretty

complicated with whirling plates and clacking shutters.

Dr.

Vladimir Zworykin, who wrote this 1948 Radio-Craft magazine article, is widely credited

for making television practical with his image orthicon, or

iconoscope,

"camera" tube for capturing real-time moving images in the transmitter. He also

made significant improvements in the cathode ray tube for projecting the images

in the receiver. RCA, for whom Dr. Zworykin worked during CRT development, owned

a trademark on the name "cathode ray tube" until it released it to the public

domain in 1950. This article focuses primarily on the iconoscope.

Progress in Television

Dr. Vladimir K. Zworykin, shown holding the image orthicon, is one of the

engineers whose work created the science of television. He is still pioneering in

the television art, as well as in other advanced fields of radio and electronics.

America's foremost television-inventor, pioneer and engineer reviews recent developments

By Dr. Vladimir K. Zworykin

The end of the war emergency has seen the beginning of two developments in the

television field in America. The first is utilization of the accumulated experience

of the war and prewar years to create an extensive, high-quality television broadcasting

service. The second is the application of television techniques to an ever-increasing

number of peacetime industrial uses, a process which is bound to result eventually

in further advances in broadcasting technique.

The first development is, reflected in the increasing numbers of station-operating

licenses issued by the Federal Communications Commission, the opening of new concentric

cable and radio relay links between stations, heavy receiver production schedules,

and the blossoming of the characteristic television dipole antennas over the landscape.

By midsummer of 1947 there were 12 television broadcasting stations in operation

and a larger number under construction. Some 70,000 receivers had been installed.

The tools of this television system are tried and tested. Following the same pattern

of private sponsorship as American radio broadcasting, television programs provide

black-and-white transmissions with a 525-line, interlaced scanning pattern. Electronic

storage pickup tubes - in particular the iconoscope and the image orthicon - are

employed both in the studio and for spot pickup. In the receivers, kinescopes serve

to reproduce the image both for direct viewing and for screen projection. These

elements play a central role in most of the television equipment to be considered.

The most important common feature of the pickup tube under consideration, the

storage principle, is illustrated in Fig. 1. The light image of the scene to be

transmitted is projected on a photo-sensitive, insulating surface - the target or

mosaic. This surface is capacitively coupled to a metal backing, the signal plate.

The light image builds up, by photoemission, a charge image on the insulating surface.

This charge image is scanned by an electron beam. As a particular picture element

is scanned, the charge stored in the element by photoemission during the preceding

picture period is released and provides the picture signal current from the signal

plate behind the mosaic to the video amplifier input.

Fig. 1 - The storage action of a pickup tube.

Fig. 2 - How the image orthicon tube operates.

Fig. 3 - Iconoscope, orthicon and image orthicon. Size decreases

as sensitivity increases.

Fig. 4 - Experiment on orthicon sensitivity.

Fig. 5 - Results of the experiment of Fig. 4.

Fig. 6 - Effect of aluminizing screen surface.

Fig. 7 - Principle of Schmidt optical system.

Fig. 8 - Schmidt-type television projection set.

Fig. 9 - Large projection televiser designed for 5 x 7-meter

screen.

Fig. 10 - Television camera at Johns Hopkins Medical Center.

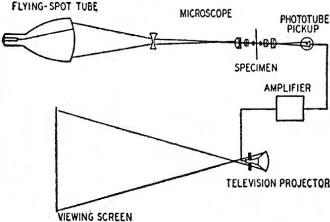

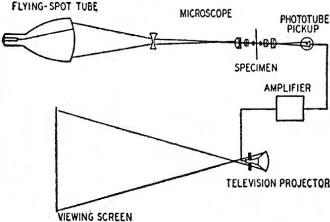

Fig. 11 - Action of the flying-spot microscope.

In the iconoscope the scanning beam has a velocity corresponding to an accelerating

voltage of about 1,000. For this velocity the secondary-emission ratio of the photosensitive

surface is much larger than unity. Accordingly the beam brings a scanned element

to an equilibrium potential which is sufficiently positive with respect to neighboring

collecting electrodes so that all secondary electrons but one per primary electron

are forced to return to the element. Under such circumstances only a small fraction

of the secondary electrons and photoelectrons emitted by the element reach the collecting

(anode) coatings on the tube walls. A majority of those which are not returned to

the element of origin are redistributed over the remainder of the mosaic surface.

This both reduces the efficiency of operation, and hence the sensitivity, of the

pickup tube and distorts the charge image formed on the mosaic by photoemission.

In practice, this distortion is rectified by the monitoring engineer by adding appropriate

"shading signals" to the picture signal.

The orthicon-short for orthiconoscope or "true iconoscope" - remedies these drawbacks

by reducing the velocity of the scanning beam on its approach to the target to such

an extent that the secondary emission ratio of the latter falls below unity; the

equilibrium potential of the target is now slightly below the potential of the cathode

of the electron gun, and the beam deposits just enough electrons on the target to

neutralize the positive charge stored by photoemission. The returning beam electrons,

just like all the photoelectrons and secondary electrons emitted by the target surface,

are collected by the anode.

Although the orthicon is, consequently, considerably more sensitive than the

iconoscope, perfectly linear in its response to illumination, and free from spurious

signals, it falls short of an ideal storage tube in two respects: (1) at very high

light levels the tube operation becomes unstable, since the target may become sufficiently

positive to pass over to its high-voltage equilibrium point under the scanning beam;

(2) the signal level is still sufficiently low so that noise introduced by the first

stage of the amplifier may impair the quality of the transmitted image.

The Image Orthicon

In the image orthicon1 (Fig. 2), the instability at high levels is

removed by providing a target screen at a voltage only slightly above the equilibrium

potential of the target to collect the electrons emitted by the latter. This makes

it impossible for any portion of the target to become sufficiently positive to result

in unstable operation. Furthermore, the signal level of the output is raised both

by inserting an image tube section ahead of the target and employing a secondary-emission

multiplier for the noise-free amplification of the signal current. The methods of

beam focusing (by a longitudinal magnetic field) and of beam deflection (by superimposed

transverse fields) are similar to those employed in the orthicon. They are designed

to produce a low-velocity spot, which is sharply focused at all points of the target.

Magnetic deflecting fields are employed throughout in the image orthicon, so that

the beam electrons which fail to be deposited on positively charged portions of

the target return along paths close to the incident beam to the area of the anode

disk surrounding the beam-defining aperture. Here they eject secondary electrons.

The electrostatic fields surrounding the anode disk are such that these secondary

electrons are drawn over into the first stage of a "pinwheel" secondary-emission

multiplier which surrounds the gun structure. Repeated secondary-emission multiplication

at the vanes of 5 successive pinwheels results in a total gain from 200 to 500.

The amplified return-beam current, representing the difference of the constant scanning-beam

current and the variable picture-signal current, provides a high-level input for

the succeeding video amplifier.

The formation of the charge image on the target presents some new features. The

light image of the scene is projected on a transparent photocathode, which is maintained

approximately 300 volts negative with respect to the target. The photoelectrons

emitted as a result are accelerated and focused by the longitudinal magnetic field

on the target, ejecting a multiplicity of secondary electrons. Picture elements

of the target which correspond to bright portions of the image assume consequently

a positive charge; the secondary electrons are drawn to a high-transmission, 20-40-mesh-per-millimeter,

metal screen placed just in front of the target.

The target itself is a very thin, high-conductivity glass film, stretched on

a metal frame. Although potential differences between its faces are substantially

neutralized by conduction in the course of a frame time, leakage from picture element

to picture element is too slight to result in an appreciable reduction in the contrast

and resolution of the picture.

The relative dimensions and general structure of the 3 pickup tubes discussed

are well brought out by Fig. 3. Increasing complexity of construction has not brought

increase in bulk.

The extraordinary sensitivity of the image orthicon is illustrated by the experiment

shown in Fig. 4. An image orthicon camera and a photographic camera employing high-sensitivity

(Eastman Super-XX), 35-mm film were both trained on the same subject. A television

receiver connected to the image orthicon camera was placed next to the subject.

Both cameras were provided with f/2 lenses and exposed for 1/30 second (corresponding

to the standard television frame time). The result of attenuating the illumination

provided by a 40-watt incandescent lamp with neutral filters is shown in Fig. 5.

It is seen that the subject is recorded by both cameras only at the maximum subject

brightness of 2 foot-lamberts or, approximately, 2 millilamberts. At the lower intensities

only the television image remains, which is still readily recognizable when the

illumination has been reduced to a hundredth of its original value.

The viewing tube, or kinescope, has undergone only minor changes in recent years.

The most important of these have increased the image brightness of projected television

pictures. Considerable gains have been recorded both in the light emission of the

projection kinescopes themselves and in the efficiency of the optics employed to

project the pictures.

Enhancement in the emission of the projection tubes has been achieved by depositing

a thin metal film - transparent to the beam electrons but reflecting for light -

over the surface of the luminescent screen. The optical effect of such a film on

light emitted backward by the luminescent screen is indicated in Fig. 6. In a tube

with an untreated screen this light, which is lost for the formation of the image,

may in part reach other portions of the screen, reducing contrast. The metal film2

both adds this light to that emitted in a forward direction and prevents this contrast

reduction. An even more important factor with high-voltage operation is that the

metal film, maintained at anode potential, prevents the screen from charging negatively.

Without such a film this charging process may reduce by a large factor the kinetic

energy with which the electrons impinge on the screen so that the energy available

for conversion into light is greatly decreased. A final advantage of the metal film

is that it absorbs negative ions originating in the cathode region of the gun, preventing

the appearance of "ion spot" without requiring special ion-trapping arrangements.

Reflective Systems

The substitution of reflective projection systems with aspheric correction for

the conventional projection lenses has led to gains by a factor from 5 to 7 in the

optical efficiency of projection systems.3 The principle of the new optical

system is shown in Fig. 7. The television image formed on a curved kinescope face

is projected by a concentric spherical mirror on the viewing screen. Such a system

is spherically symmetrical about the common center of curvature of mirror and tube

face, and hence provides an image field free from optical defects apart from spherical

aberration. If the latter is corrected by placing a weak aspheric lens at the center

of curvature, there results a wide-angle, large-aperture system free from all lower-order

optical defects. The preparation of the aspheric lens, it is true, presents a difficult

mechanical problem. However, a plastic molding technique makes it possible to prepare

large numbers of such lenses from a single steel master. This procedure has rendered

it economically feasible to employ reflective projection systems in home receivers,

arranged as shown in Fig. 8. The image on the tube is projected upward and deflected

by a 45° mirror onto a vertical directional viewing screen. The optical efficiencies

of such systems have been found to range from 18 to 35%, as compared to 4-5% for

an f-2 projection lens. Fig. 9 shows an earlier television projector operating on

the same principle, but designed to cover a motion picture theater screen 5 X 7

meters in dimension.

The equipment described so far primarily finds application in current television

broadcasting and reception. However, its utility is by no means limited to broadcast

television. Numerous other uses may be conveniently grouped under the heading "industrial

television."

Many Other Uses for Television

An application of obvious importance is the employment of television equipment

to observe industrial processes which are either inaccessible or dangerous to human

beings; the Bikini atomic bomb observations are a relevant example. Other uses are

deep-sea observations and the surveillance of boilers in power plants. A similar

type of application is the watching of a series of widely separated, automatic substations

from a conveniently located . central point. Here television enables one individual

to observe simultaneously events taking place at widely separated points. The converse

problem, of permitting a group of individuals, too large for direct viewing, to

observe the same point is met not only in broadcast television, but also in department

stores, to let customers view fashion exhibits at widely separated sections of the

store; at conventions, to permit an overflow audience to watch the proceedings;

and, perhaps most significantly, in medicine, to give consulting and visiting physicians

an intimate view of an operation without interfering with its progress. Fig. 10

shows a television camera suspended for this purpose directly above the operating

table in an operating room of the Johns Hopkins University Hospital.

Television techniques also find valuable application in fields which, at first

sight, seem only very remotely related. One of these is projection microscopy. Many

years ago the ultra-violet and infrared sensitivities of the iconoscope and the

image tube were utilized to permit the eye to see enlarged images of microspecimens

formed with these invisible radiations. The flying-spot microscope, shown schematically

in Fig. 11, serves instead to present the greatly enlarged microscope images to

extended audiences, with a brightness which is independent of the illumination of

the specimen. For this purpose a television scanning pattern formed on the very-short-persistence

fluorescent screen of a cathode-ray tube (a "flying-spot tube") is imaged by a high-resolution

optical microscope to greatly reduced scale on the microspecimen. The transmitted

light is directed by a second microscope objective onto the cathode of a multiplier

phototube. The amplified output signal of the latter modulates the beam current

In the kinescope of a television projector which forms a greatly enlarged image

of the microspecimen on a screen, its deflection being synchronized with that of

the flying-spot tube.

Many of these developments are still in an experimental stage. However, they

illustrate the fact that television broadcasting represents but one phase of the

application of television techniques. Industrial television offers a possibly even

broader range of opportunities to the researcher and experimenter and may be expected

to develop into a tool of increasing value in the coming years.

1 A. Rose, P. K. Weimer, and H. B. Law, "The Image Orthicon - A Sensitive Television

Pickup Tube," Proc. Inst. Radio Engrs., Vol. 84, pp. 424-432.

2. D. W. Epstein and L. Pensak, "Improved Cathode-Ray Tubes with Metal-Backed

Luminescent Screens," RCA Review, Vol. 7, pp. 5-10, 1946.

3. D. W. Epstein and I. G. Maloff, "Projection Television," J. Soc. Motion Picture

Engrs., Vol. 44, pp. 443-455, 1945.

Posted October 29, 2019

|