|

December 1947 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Short wave radio was a boon

to both professional and amateur radio operators because of its ability to be received

over longer distances using significantly lower transmitter power. In 1947 when

this article appeared in Radio-Craft magazine, the problem was (and still

is) that short wave bands typically suffer from atmospheric ionization effects that

vary depending on time of day, local weather, solar activity, pollution, and other

phenomena. Long wave's advantage was that although it required higher power and

longer antennas, it was (and is) extremely reliable. For other than the most critical

applications, idiosyncrasies of short wave communications were accepted as the price

of more convenient and lower cost operation. Widespread adoption of short wave communications

brought extensive studies and characterization of atmospheric influences in particular

frequency bands. Discovery of distinct "F" layers (regions) in the ionosphere and

their effects on radio transmission has allowed radio operations to predict and

accommodate the affected propagation paths. What does the "F" in F-Layer mean? According

to my sources the "F" refers not to frequency, but to "free" electrons in the ionosphere.

Here are a few really nice propagation prediction website that give up-to-the-minute

data: HamQSL.com,

ARRL.org,

DX.QSL.net,

VOACAP.com,

DXZone.com,

SolarHam.org

How to Use Radio Propagation Predictions

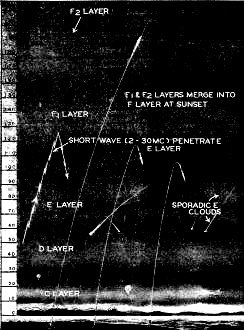

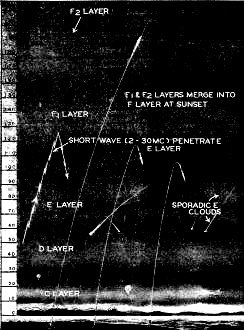

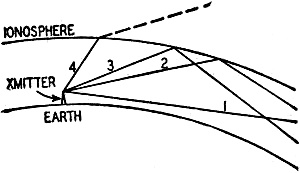

The various layers of the atmosphere. Though all affect radio

transmission at certain frequencies, F-layer reflections are most important for

long-distance communication. Scale at left in miles.

By Fred Shunaman

Old-timers remember when the best radio wave was the longest one. The long wave

was reliable. It maintained the same strength day and night at all times of the

year, and the strength dropped off steadily with increasing distance from the transmitter.

Short waves - roughly those under 1000 meters - were "unreliable." They varied in

strength with the time of day and the season and showed other "unpredictable" vagaries.

The reliability of the long waves was obtained at the cost of high power. With

the coming of broadcasting, it was found that a station of a few hundred watts could

be heard (when conditions were good, such as on a cold winter night) farther than

a long-wave station of many kilowatts. Then the amateurs started to work at even

higher frequencies, first on 150 meters (2 mc), then 80 (3.5 mc), later 40 and 20

(7 and 14 mc). At each increase of frequency they were able to transmit farther

with less power.

But other and more disquieting discoveries were made. A station which pounded

in with ear-splitting volume one night might simply not be there at all the next.

Amateurs found they were not able to communicate with old friends in the next state,

but were being received solid several thousand miles away. Thus was "skip distance"

discovered. One point was clear: if some way could be found to figure out these

high frequencies, a new era in low-power, long-distance communication would open

up. Scientists amateurs, and communications companies set out to learn more about

these mysterious waves.

First, the scientists Kenelly and Heaviside suggested that the upper parts of

the atmosphere were ionized - that the ultraviolet rays of the sun break up the

atoms in these upper regions where the air is so thin as to resemble a poorly exhausted

vacuum tube - into negative electrons and positive ions. These upper regions of

the atmosphere, they said, were filled with a partly conductive material, something

like the interior of a gas-filled vacuum tube. This ionized layer reflected radio

waves of high frequencies back to earth, but lower-frequency waves were merely absorbed

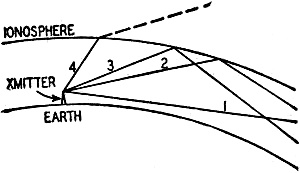

by it. The higher the frequency, the farther the waves penetrated the layer; thus

the greater the distance at which the reflected wave reached the earth (Fig. 1).

Above a certain critical frequency, the waves keep right on through the layer and

are lost to earth entirely.

In 1923 the English scientist Appleton proved the existence of the Kenelly-Heaviside

layer by beaming radio waves straight up and measuring the time the reflected waves

took to return. He found that the higher-frequency waves took longer to come back,

proving that higher frequencies penetrate farther into the layer.

Height of the layer as measured by this earliest radar was about 70 miles. But

as frequencies were raised toward 3 mc, the echoes suddenly disappeared - to return

from a distance of more than 150 miles. Obviously there were two reflecting layers.

Above 8 mc a double echo was noted, as if the higher layer were split in two.

Fig. 1 - Long waves follow path 1, shorter ones, 2 or 3,

and very short waves, path 4.

The lower layer is now called the E-layer, and the higher one - or two - the

F1- and F2-layers. The F2-layer is the most important one to long-distance, high-frequency

communication. The E-layer is more important in daylight and at frequencies below

4 mc, though at times its effects may be felt up to 20 mc. Below these layers are

the C- and D-layers, whose effects on radio waves have been little studied, but

which are beginning to be considered important at certain frequencies.

The Bureau of Standards at Washington has been one of the leading explorers of

the ionosphere, and began in the late '30's to issue rough predictions of the probable

ranges at various frequencies. The predictions were very approximate, and covered

only four periods-summer and winter noon and midnight.

The demand for reliable radio communication during World War II made much more

detailed and accurate knowledge of ionosphere conditions necessary. Numerous stations

were established at widely scattered points, and continuous records were made and

transmitted to Washington for interpretation and correlation with those from other

stations. These stations now number 58, and gather ionospheric data from all parts

of the earth. The Central Radio Propagation Laboratory (CRPL) of the Bureau of Standards

uses this information to issue monthly predictions of usable radio frequencies.

These are put out in the form of monthly booklets, 3 months in advance. They contain

maps and charts showing the maximum usable frequency for communication between any

2 points on the earth's surface at any time of day. The booklets are entitled Basic

Radio Propagation Predictions and are used in connection with another publication,

Instructions for the Use of Basic Radio Propagation Predictions (Bureau of Standards

Circular 465), which contains further maps, charts, nomographs, and instructions

for use with the Predictions.

The Predictions consist of a series of charts of the ionosphere. Fig. 2

is one of them. The maps show the maximum usable frequencies (muf) for points at

4000 kilometers away from any point on the earth at any given time of day. Points

on the same latitude do not have the same ionospheric conditions at the same time

of day throughout the world. Therefore it is necessary to have 3 sets of charts.

The western (W) chart includes South America, all the United States but the northwestern

tip, most of Canada, the Atlantic Ocean and a bit of Africa. The eastern (E) chart

is applicable to Asia and Australia, and the intermediate (I) to Europe, Africa,

northwest Canada, Alaska, and a belt of the Pacific.

Fig. 2 - One of the ionosphere charts. There are six of

these F2 and one E-layer chart.

Fig. 3 - Part of the world map, showing the two great-circle

paths mentioned in the text.

Predictions Not Easy to Apply

The Predictions are not particularly easy to use. It is often necessary to use

2 charts in conjunction, checking them against a third when the E-layer may affect

results. A further difficulty is that radio waves follow great-circle paths, while

the charts are square Mercator projections. This difficulty is solved with a great-circle

chart in the Instructions. To use the Predictions, put a piece of tracing paper

over the map of the world in the Instructions (Fig. 3). Mark the points between

which communication is to be established. Also trace the equator line on the tracing

paper. Then place the tracing paper on the great-circle chart (Fig. 4) with

the equator lines coinciding, and slide it back and forth until one of the curved

lines on this chart connects the 2 points. Draw the great-circle path between them

along that line. Put the tracing paper on the correct ionosphere chart with the

local station on the vertical line marking the local time of desired communication.

Finding the correct frequency now depends on whether the distance is more or

less than 4000 km (2500 miles).

If the distance is exactly 4000 miles" the problem may be relatively simple.

The mid-point of the great-circle path is located and the maximum usable frequency

(muf) read direct from the F2 4000 chart for the given zone. For example, suppose

contact is to be made between New York and Georgetown, British. Guiana, a distance

of approximately 4000 km. The tracing paper is placed over the world map and the

2 points, as well as the equator, are marked on it. Then the paper is placed over

the great-circle chart and moved back and forth till a great circle joins the 2

points. The path between the two is drawn, as well as the mid-point of that path.

The tracing paper is then placed over the F2, 4000 W map with the equator lines

again coinciding and the New York point on the hour meridian of the time desired.

The muf of the mid-point is read. For example, in December 1947, the muf of the

mid-point of the great-circle path between New York and Georgetown is 21 mc for

6 am, 34 mc for 12 noon, and 21 mc for 6 p.m.

Since unpredictable conditions may cause the predictions to be in error, a frequency

15% lower than the. muf is taken as the optimum working frequency (owf). Thus all

muf's are multiplied by 0.85 for actual working frequency.

If the distance is greater than 400 km, 2 points 2000 km from each end of the

path are taken instead of the mid point. The tracing paper is placed over the map

as before and both points, as well as the equator, marked. The meridian of Greenwich

may be drawn also, as a time reference. It is usually easier to use it for great

distances than the local time of either of the 2 stations at the ends of the path.

The great-circle chart is again used to find the actual radio path between the 2

points. Instead of marking the mid-point of the path control points 2000 km from

the ends of the path are marked. (Experience has shown that muf's at great distances

are little different than at 4000 km.) The maximum usable frequency for each of

these points is found (on the appropriate chart) and the lower of the two taken

as the muf for the entire path.

For example, communication between New York and Shanghai is desired. Drawing

the path and control point the muf's for the New York control point are found to

be 28, 12, and 12 mc for 0600, 1200, and 1800 GMT, respectively. At the Shanghai

end. using the F2 4000 E chart (not shown) all 3 muf's are found to be 12 mc. The

muf for the whole distance is then 12 mc for the given times, and the owf 10.2 mc.

For distances less than 4000 km a little more work must be done. The muf is first

found exactly as for the 4000 km. Then the muf of the mid-point found on the F2

0 chart, which shows the critical frequencies for waves projected directly up from

the sending station. Since the distance is between 0 and 4000 km, it might be expected

that its muf would be between these two. And so it is, but in a way that does not

vary directly with distance. A nomograph provided in the Instructions for distances

less than 4000 km. A straight edge is placed between the muf at 0 and that at 4000

km, and the correct frequency is read where the straight edge intersects the line

representing the distance of the station with which communication is to be established.

Fig. 4 - This great circle chart is used to find the radio

transmission paths on Fig. 3.

At lower frequencies the E-layer may enter into the picture. An E-layer chart

in the Predictions helps the radioist to use reflections from that layer. After

selecting the best frequency from the F charts, consult the E chart. If the E-layer

muf is higher than that reflected by the F-layer, use the E-layer frequency.

Adapting the Predictions

All these methods are excellent for transmission between 2 fixed points, such

as 2 commercial or government stations. They are not so good for the amateur or

short-wave listener. The amateur wants to know what frequencies to use to cover

a large area - possibly a continent - or in what direction to send a CQ to get results

and dx on his transmitter's frequency. The short-wave listener would like to find

out when to listen for elusive short-wave broadcasters. Both are on the alert for

times when higher frequencies than those predicted are useful, for these are the

periods of dx.

A few attempts have been made to broaden the scope of the Predictions to cover

amateur and general requirements. The most successful of these is based on the observation

that a given muf "cloud" drifts along the earth from east to west, maintaining a

constant angle with the sun. The amateur who works on 10 meters, for example, can

note the area over which 30 mc or higher is the muf. If this area. covers the control

points between him and any desired station, he can work that station on 10 meters.

Another system calculates owf's for narrow strips along the American coast and that

of other countries.

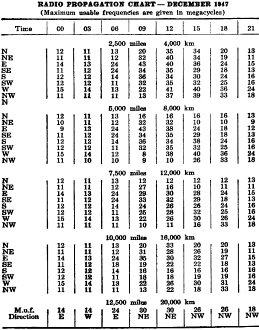

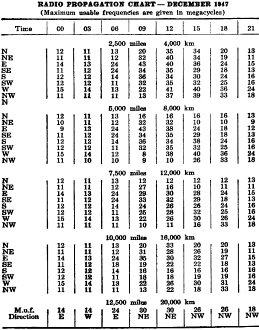

The table presented here represents a new approach to the problem. Based on latitude

40 N in the western zone, a large number of calculations have been made, giving

the optimum frequency for any part of the day for any distance and any direction.

As conditions drift west with the sun, this chart will be correct for any part of

the United States on the 40th parallel, and approximately correct for considerable

distances north and south of that line.

Radio Propagation Chart - December 1947

(Maximum usable frequencies are given in megacycles)

The table shows conditions at intervals of 3 hours and at ranges from 2500 miles

(4000 km) to 12,500 miles (20,000 km) at intervals of 2500 miles. These intervals

are close enough to permit interpolation for times and distances between those given.

The same is true of directions.

Use of the table is simple. The user merely consults it for the current hour

and notes the optimum working frequencies in each direction for the various ranges.

A combination of high working frequencies and great distance spells dx. Low frequencies

in a given direction indicate the limits within which a receiver or transmitter

should be held to work or hear from stations in those great-circle directions.

A great-circle chart based on a point near the user's location is exceedingly

useful for ascertaining the bearing of distant points. Less convenient is the chart

published in the Instructions, but distances as well as directions can be obtained

from it. A globe and piece of string is possibly the simplest means of finding direction

and distance.

For example, to find the muf for working between New York and San Francisco at

9 p.m. Eastern Standard Time during December, 1947, first find the bearing and distance

by any of the means above. The distance is between 2500 and 3000 miles, and thus

fits most closely the 2500-mile table. Bearing is a little north of west (in spite

of the fact that San Francisco is south of New York). At 21 hours the maximum usable

frequency west is 24 mc. For reliable work this should be converted to the optimum

working frequency (owf) by multiplying by 85%. The owf is then about 20.5 mc. The

nearest amateur band is 14 mc, though short-wave listeners may look for Treasure

Island right up to its 21-mc frequency.

Again, suppose a short-wave listener is interested in getting Shanghai or Nanking.

Distance is ascertained to be approximately 12,000 km and the bearing slightly west

of north. Looking at the chart, it appears that 13 mc at 9 p.m. offers the best

opportunity, as read from the 7500-mile chart in the direction N. Checking with

NW, the best times appear to be between 3 and 9 p.m., with a frequency as high as

33 mc at 6 p.m. However, the bearing is much more nearly north than northwest, leaving

9 p.m. the best hour.

Only one direction is given for the 12,500-mile range, as it is the same distance

in all directions. There is very little difference in muf over a wide angle from

NE to NW. The operator with a rotatable antenna may find it worth his while to try

various paths.

|