|

March 1963 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Cathodic protection is a

major field of electronics and electrical distribution. It has two primary forms

- galvanic and impressed-current. The goal of each is to negate the electrical

current between dissimilar metals which leads to corrosion. The galvanic method

typically uses a passive sacrificial metal element to dominate the electron migration.

An example is the

anode rod inside your hot water heater (HWH). Most people have no idea they

exist and are supposed to be checked regularly and replaced as needed. It's fairly

easy to do, requiring shutting off the water supply and draining the tank below

the level of the top. Once a year, I also open the drain valve at the bottom of

the HWH to rid it of any debris. Impressed-current cathodic protection

is more sophisticated and involves injecting a counter-current in an engineered

system to cancel out destructive currents. This "Cathodic Protection" article from

the March 1963 issue of Radio-Electronics magazine is a good primer for

the science behind it.

Cathodic Protection - The Big Electronics

200,000 square feet of cathode and 32-pound anodes spell out

electronics in capital letters.

By Cecil Beeler

"Our cathodes average 50,000 square feet, calling for ten 32-pound anodes with

a 30,000-ohm coating in our notorious 500-ohm soil. We take our potentials spring

and fall. If the variation is over 0.15 volt or the average under -0.80 volt to

a copper-copper-sulphate electrode, we check the section with a current requirement

meter and sweep out trouble with audio tracer. We're catching a lot of contacts

and holidays but hardly any defective insulators or hot spots."

This wacky, yet strangely familiar jargon is the native tongue of cathodic protection,

the Texas-size member of the electronics family, natural-gas utility branch.

Cathodic protection reverses the nature of things so that buried steel, such

as a gas main, becomes cathodic to the electrolytic soil moisture it contacts. Anodes

corrode, but a cathode repels the negative ions that do the damage.

Natural-gas pipeline companies are the greatest users of cathodic protection.

They and their consultants have developed the instrumentation to provide perfect

protection of buried steel, whether in a gas main or other structure.

Few technicians work more closely to their basic science or depend more on instruments.

If some hard-bitten shopman is inclined to argue that the deal isn't electronic

(granted, cathodic protection doesn't output toward a speaker coil), let him pick

out his instruments and tramp his vast "chassis," of which nothing is to be seen

but test boxes at every 1,000 feet or so.

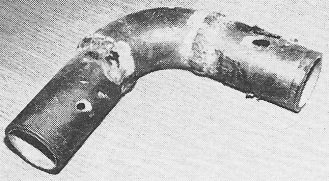

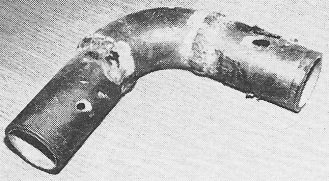

Enemy attack. This section of gas main was holed in three places

by galvanic corrosion.

Cathodic protection is properly added even to coated steel. Here it protects

against defects in the coating. Even a puncture as small as a pinhole in the coating

leads to corrosion that will eat a hole the diameter of a pencil through the 3/16-inch

wall of a gas main in as little as 2 years. Cathodic protection keeps corrosion

in check at any exposed patches of steel at a cost of 1/4 of 1% of the cost of the

gas main.

Cathodic protection is also added, a slightly higher cost, to bare and possibly

badly corroded pipe to prevent further damage.

Corrosion Principles

It's all deceptively simple. Who hasn't seen zinc and sulphuric acid combine

into zinc sulphate? End of experiment - but it wasn't corrosion.

A galvanic cell - say a shorted "flashlight battery" - contains all the elements

needed to illustrate the case: a metal, zinc, in contact with a dissimilar conductive

material, in this case carbon, both immersed in a moist earth-like electrolyte.

The electrons flowing from zinc to carbon through the short, in effect, ride horseback

on ions through the electrolyte to the zinc. We know what becomes of a battery's

zinc as it is swept over by metal-hungry negative ions.

Studying a corrosion tubercle (see "Enemy Attack" photo) you can almost see the

hungry negative ions back out of the hole they are chewing to spit out a mouthful

of iron, then go back for another bite. Actually, soil oxygen takes out the iron

as oxide, freeing the ions to repeat the process and carryon the corrosion as long

as a particle of metallic iron remains.

Right about here is where the big electronics takes over. Break up a galvanic

cell and you break up its corrosion but, try as you might, not every last cell can

be exterminated.

If you're thinking that, since the trouble is entirely caused by negative ions,

why not shoot a negative bias potential into the metal to be protected and blast

out the attackers, you're a genius. You have just re-invented cathodic protection!

It doesn't take much. The current required to protect coated pipe is up to 15 μa

per square foot.

Iron is about the most difficult to protect. It is anodic to about three-quarters

of the common metals. It also seems to delight in being anodic to itself, with endless

chances for galvanic cells to be formed. Between ferrous iron (the most anodic form)

and ferric iron lies a rising scale of seven gradually less anodic metals.

Welds may be anodic to the parent metal, malleable iron anodic to mild steel,

and even new steel to older steel of the same composition.

However, magnesium and zinc are anodic to iron and are satisfactory in other

ways. They are available as ingots weighing up to 32 pounds, prepared with a wire

for attaching them to the iron. When installed, each anode, as it is commonly called,

supplies more than 1 volt for cathodic protection and up to about 250 ma for 5 to

10 years for the largest size.

The job can also be done by feeding negative DC to the pipe, with a carbon or

other corrosion-resistant buried anode to complete the circuit. This method is favored

for the big cross-country pipelines. Tapped transformers and rectifiers with a top

of about 18 volts are usually used.

Test Equipment

How to trace a shorted cathode, 5000 square feet or more of cathode,

that is. Hook up an audio pulse generator to your cathodically protected gas main

and a ground probe (left). Then, with the receiver unit, follow the beep-beeps as

they take a path to ground through the short.

Using a special-purpose multimeter to check the cathodic protection

voltage of a section of main.

A short circuit is as disastrous to cathode protection as to any electronic rig.

So is loss of power supply, imbalances and those faults that are supposedly impossible.

Many a protection area is found to be as full of what-is-it and where-is-it as a

junior science superhet.

And all this 3 feet under sod and paving. Small wonder that any cathodic protection

instruments that come into your hands show distinct signs of wear.

A soil resistivity tester is often used throughout an area to determine how corrosive

the soil is likely to be, before any steel is installed. One such instrument is

hooked to a row of four small probes shoved in the ground. A careful reading, a

simple multiplication, and the average soil resistivity is obtained to the depth

of the spacing of the two inner probes. In soil that measures over 10,000 ohms per

cubic centimeter, corrosion is expected to be light. If resistance is 1,000 ohms,

corrosion will be serious.

After the pipe is laid, this instrument may be used to find belts of more corrosive

soil that are making "hot spots," conducive to uneven protection.

A good DC voltmeter with a 0- to 2- or 3-volt scale is the workhorse of cathodic

protection instruments. "Pipe-to-soil" from aboveground parts of the steel, or test

wires from it in permanent check-point terminals, show whether the cathodic protection

is effective. Contact with the soil is made through a standard soil electrode, available

in the trade, which makes the needed electrolyte-to-electrolyte contact through

a porous bottom plug.

Recommended sensitivity for this work is 50,000 ohms per volt or better. A 20,000-ohm

vom can do the job, except for an occasional low figure due to loading the electrode's

contact area. For a vtvm you would need a portable power supply. Best of all is

a potentiometer-voltmeter which is rated up to 100,000 ohms per volt.

An audio tracer is the hardest-working instrument when cathodic protection trouble

is to be cleared up.

It leads the receiver-bearing operator by the most direct electric route from

the transmitter to the nearest and biggest short to ground. On the way it ticks

out patches of bare steel on coated mains with a hint as to the area of each one.

A U-core coil can be plugged into the receiver and used to examine an insulator

that is less than 1 ohm to ground on both sides, and report whether it is good or

not. The same coil can explore a network of pipes and point to the exact point at

which the signal meets a short.

These instruments were designed only for tracing underground pipe or cables.

Their use in spotting protection trouble was discovered at about the same time by

several gas utilities.

They pour a ground-seeking audio pulse of no more than 1,000 cycles for a sine

wave, or the hashy output of a buzzer circuit, into the pipe. This signal promptly

flows to the holes that were making havoc for the cathodic protection and there

dissipates.

Pipe locators that work on the beat frequency of two low RF oscillators when

used this way are ... well, they are good pipe locators.

Problems Do Come Up

Now let's examine a typical every-day problem. A 10,000-foot length of 8-inch

coated pipe has a potential of about 0.8 volt, a little low, which dips to 0.68

volt in one reading. The current taken is 300 ma, up 50 ma from the previous reading.

Since this size pipe is about 20 miles per ohm, the IR drop at 300 ma maximum

would be too small to work out, except with a very sharp pencil. Could be a hot

spot, a drift of extra corrosive soil, but a hot spot doesn't move in between readings.

A short would drag much more current and much lower potentials than those found.

That left the suspicion of a large area of bare metal, such as could be caused

by damage while excavating near the pipe. The escaping electrons set up a potential

gradient as they flow through the soil, which, in this case, would amount to 0.12

volt subtracted from the applied 0.80 volt between the pipe and average soil.

The audio tracer was called in and readily spotted the bare surface at a point

found to have been the scene of repair work. It could have been dug up and retaped,

but it was easier to install an extra anode to cancel out the dangerous voltage

gradient.

Bibliography

Fundamentals of Galvanic Corrosion, Lauderbaugh (Pamphlet). American Gas Association,

420 Lexington Ave., New York 17, N. Y.

Proceedings of Annual Appalachian Underground Corrosion Short Course, (Papers

of graduated and classified lectures). West Virginia University Bulletin, Morgantown,

W. Virginia.

Posted May 3, 2023

|