|

July 1963 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Attempts at making an electronically

printed facsimile (fax) of an original document at a location distant from the source

have been around for quite a while. As mentioned by Radio-Electronics magazine

editor Hugo Gernsback in this article, Samuel Morse had a crude working device for

printing messages on paper even before his eponymously named code of dots and dashes

became famous in 1837. A couple decades earlier, a fellow named

John Redman

Coxe, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, devised a method of electronically printing

images and text on paper using a conductive solution and a direct current pile (aka

battery). Dr. Coxe, a physician, is not a well-known figure in the electronics

world, but in his day he was a prominent experimenter in the field of electrochemistry.

That was the era when people were applying charges to frog legs to get their kicks

making them kick ;-)

Electronic Test Paper

Ordinary linotype slug used in the electrical printing experiment.

By Hugo Gernsback

Many inventions have a way of becoming forgotten, when later improvements supersede

the original.

In American literature, Samuel F. B. Morse is universally acknowledged as the

inventor of the telegraph, as of the year 1837. He deserves credit for the idea

of tracing on a moving paper tape a zig-zag type of code, for which he was responsible.

The telegraphic tracings could be made with an ordinary pencil or pen. The "Morse

Code" came many years later.

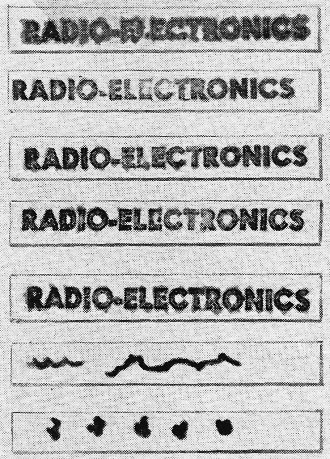

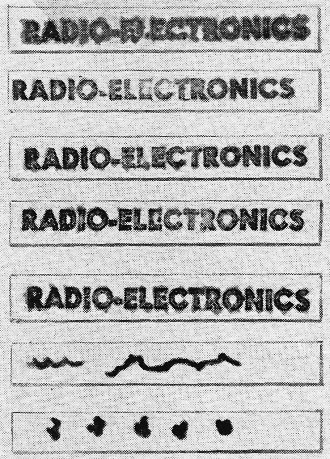

Several lines printed electrically from linotype slug on the

special test paper. The two last lines were made with the negative wire touching

the test paper.

Much less known is the fact that long before Morse, John Redman Coxe of Philadelphia

was probably the first inventor of any electrical telegraph (1810). Coxe's telegraph

was a chemical one. Papers which we know today under the name of litmus and other

similar test papers, have been around for more than 150 years. Coxe used a wet band

of chemical paper which recorded signals in color when a battery was connected to

the recording stylus.

A similar chemical telegraph was invented in 1846 by Alexander Bain, a Scottish

electrician and inventor.

For many reasons, today we can make good and practical use of chemical test papers,

particularly in testing polarity, which otherwise requires instruments such as voltmeters.

For a few pennies, experimenters can make an excellent polarity indicator which

the present writer used more than 60 years ago and which still works well for anyone

who wants to try it.

First you require the type of paper known as Turmeric Test Paper. This can be

obtained from large drug stores or directly from the Fisher Scientific Co., which

has offices in many large cities.

This paper usually comes in yellow strips about 2 inches long and about 1/4 inch

wide. It must first be made conductive by dipping it in an ordinary salt solution.

Then place the paper on a metal plate or thick tinfoil and connect one wire - the

positive - to the plate. Use a 6- to 9-volt battery. The positive pole makes no

impression. The negative wire, however, gives a brilliant red color.

Samples shown in the photographs here show how this is done. The one imprinted

Radio-Electronics was made by obtaining a metal linotype slug with the words Radio-Electronics

on it, to which was connected the negative pole. It imprinted the entire name excellently,

as will be noted. If you want a permanent record, you need about 6 to 9 volts and

the contact should last for a few seconds. This will make it indelible. The imprint

will vary depending on the voltage used as well as the duration of the contact.

Experimenters will find a good use for this Turmeric paper, which is cheap and has

many other uses, such as testing chemicals, as well. Thus for instance a solution

of ordinary borax stains the yellow paper red.

|