|

April 1958 Radio-Electronics

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The

iconumerator (electronic particle counter), the vidicon tube (TV image recorder),

the Electro Importing Co.'s Telimco (world's first home wireless outfit), the

Wireless

Association of America (founded before ARRL), the Dynamophone (voice-activated switch),

the "Swatties" (members of the Society of Wireless Telegraph Engineers), the "Detectorium"

(silicon crystal detector), Ralph 124C 41+ and his sweetheart Alice 212B 423 (Gernsback

sci-fi series) were covered. Radio Amateur News predated QST as America's

premier magazine for Hams, the famous 1919 "Verboten" cartoon (protested limitations

on private radio operators from the wartime era), the de Forest "Oscillion," Major

Armstrong's superregenerative circuit, the first "network" broadcast (WEAF in New

York City and WNAC in Boston), the Reinartz, the Super, the Autoplex, the Solo dyne,

and the Neutrodyn (home radio receiver kits), Tec-Teleducation (audiovisual classrooms),

variable mu, metal, tuning eyes, octal, loctal, and acorn tubes, and much, much

more was reported in Hugo Gernsback's many electronics publications during the half

century period that began in 1908. Read about them all in this extensive article

written by Tom Kennedy.

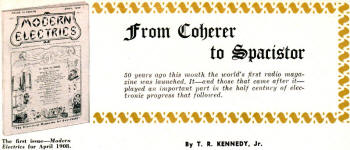

Half a Century of Electronics Publishing - 50th Anniversary

50 years ago this month the world's first radio magazine was

launched. It - and those that came after it played an important part in the half

century of electronic progress that followed.

The first issue - Modern Electrics for April 1908.

By T. R. Kennedy, Jr.

half century ago - April, 1908 - Modern Electrics,

the world's first publication designed to explain and popularize "wireless," was

published. Its editor and founder, Hugo Gernsback, was a Luxembourgian who had come

here in 1904 as a youth of 19, to market his first invention, a layer-built dry-cell

battery. half century ago - April, 1908 - Modern Electrics,

the world's first publication designed to explain and popularize "wireless," was

published. Its editor and founder, Hugo Gernsback, was a Luxembourgian who had come

here in 1904 as a youth of 19, to market his first invention, a layer-built dry-cell

battery.

With his new battery - which he had patented in Europe - the young inventor brought

many new ideas and devices with him, It was not long, therefore, before a new company

to import, manufacture and market devices for the electrical and the new group of

"wireless" experimenters, made its appearance. Called the Electro Importing Co.,

it occupied a small loft at 32 Park Place, later a larger one at 87 Warren St. and

still later at 84-86 West Broadway, in lower Manhattan; a little later, there was

added a retail store at 68 West Broadway, the world's first radio store.

Among other items, the E.I.Co. began marketing the first home or private radio

ever offered the public. Called the Telimco (from The E.I.Co. name) wireless telegraph

outfit, it was advertised in Scientific American in January, 1906. Sales

were slow at first - the new company had to convince not only the public but the

police that the device would send signals through the air without wires - but it

soon became the most important product of the E.I.Co. The original Telimco model

is now in the Ford Museum at Dearborn, Mich.

Early picture of the Electro Importing Co.'s first retail store

- the world's first radio store - and the type of equipment that was sold before

1910.

So much explanatory material was needed in those days to tell about what the

Electro Importing Co. had to sell to electrical experimenters and wireless enthusiasts

that the company's voluminous catalog often contained long explanatory articles.

Gernsback found himself already a publisher of electrical and wireless information,

and it was but a step to a regular monthly periodical.

Though he used the conservative Modern Electrics as a title (a "radio"

magazine pure and simple could hardly have survived in 1908) the very first article

of that original April issue was titled "Wireless Telegraphy." Another article

"by our Brussels correspondent" described a wireless-equipped automobile. There

was also a piece about long-distance records established by the United States fleet,

whose transmissions from the west coast of Mexico had been received at San Francisco

and at Pensacola, Fla.

The first issue contained 40 pages. Price was announced as 10 cents a copy -

$1 per year.

In the very next issue of Modern Electrics (May, 1908), Gernsback elaborated

on his Telimco dot-and-dash wireless with an invention he called the Dynamophone,

in which the human voice, through a microphone, coupled to a spark coil, transmitted

to a distant receiver enough energy to operate a relay and start an electric motor.

This might be called the great-granddaddy of today's numerous voice-operated systems

now used in oceanic radio and elsewhere.

In subsequent issues he commented on the electric tubes then in existence, based

on the Geissler and Crookes bulbs. July's Modern Electrics carried an article

by V. H. Laughter on "Speaking Arc Lamp," forerunner of the high-power arc transmitters,

the arc flame of which was "modulated" by stepped-up voice frequencies. About a

year later, Valdemar Poulsen developed and announced an arc transmitter that covered

150 miles on first test. Laughter, incidentally, has continued as an author in these

magazines to present times. One of his latest articles (June, 1950) was on "Making

Large Electrets."

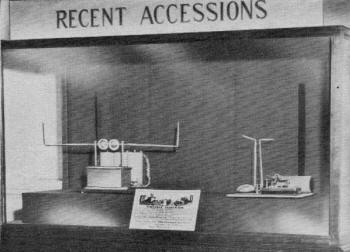

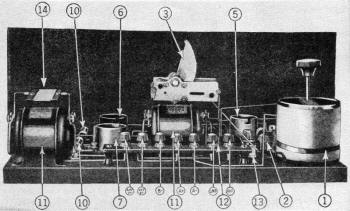

Replica of "the first radio set ever sold to the public," a small

spark transmitter and receiver, now rests in Ford Museum at Dearborn. This set was

demonstrated at the IRE convention in 1954, the last time spark transmission was

authorized by the FCC.

A "loud-speaking telephone," which could be heard without pressing the device

against the ear, was offered by the Modern Electrics Berlin correspondent

in the September, 1908, issue. Actual contact with the ear, and thus the possibility

of picking up germs from the device, was said to be avoided. No other use was foreseen.

The Wireless Association of America was promoted in 1909, to further

the interests of wireless telegraphy and "aerophony" in America. There were two

conditions of membership - American citizenship and ownership of a sending or receiving

set (or both). Lee de Forest was the first president. From the membership of this

organization and the "Swatties," or Society of Wireless Telegraph Engineers, of

Boston, grew the present-day Institute of Radio Engineers, which came into official

being on May 13, 1912.

A prominent article in the May, 1909, issue was titled "Signaling to Mars."

In those days it was thought that a power of 70,000 kw would be necessary. This

could be supplied, the article pointed out, by focusing many high-power long-wave

stations on Mars from various spots on Earth, synchronizing them to operate at the

same time from a single key.

Not content with pioneering in the new world of wireless, Modern Electrics

boldly attacked the unattainable objective of sending pictures through space. In

an article "Television and the Telephot" in December, 1909, several approaches and

proposals by leading experimenters were described. All included a mosaic of selenium

or other light-sensitive cells as a transmitter and a similar mosaic of small lamps

to form the receiving screen. The state of the art had apparently not advanced to

the point where a synchronized scanning system could even be visualized. Gernsback

proposed a method whereby the large number of wires could be cut down by using different

frequencies and tuned relays, and whereby varying light intensities could be reproduced

with varying current strengths. This was said to be necessary to transmit images

of objects in motion and to give a recognizable image. No patents were taken out

on the device, as it was considered too complicated for practical realization in

the form described.

Modern Electrics, now grown to a circulation of more than 30,000, lent

its issue of April, 1910, to the complete printing of the proposed Burke Wireless

Bill, which was devised to "regulate and control the use of wireless telegraphy

and wireless telephony." This was one of the first actions in the struggle against

Federal attempts to "regulate" the amateur into oblivion or ineffectiveness, in

which the Gernsback publications were to take so active a part.

An early E.I.Co. scene. Not only was manufacturing and shipping

carried on here, but Modern Electrics was edited on the premises too.

In Modern Electrics of May, 1910, it was learned that Bellini and Tosi,

two Italian experimenters at Boulogne, whose work had been reported on in the March

and May, 1909, issues, had devised a system of directing wireless waves in space.

The process could be reversed - incoming waves could reveal the direction from which

they arrived. And so was born one of the earliest direction finders.

In the same month the entire organization moved into a roomy 5-story building

at 233 Fulton St. Celebrating the new quarters, Modern Electrics carried

a leading story from Thomas A. Edison on a new nickel-iron storage battery, which

Edison had toiled 6 years to perfect.

The editor told of his new "Detectorium" in July, 1910. It incorporated a silicon

crystal detector as an integral part of a double-slide tuning coil. The blunt silicon

point, held in a brass cup, contacted the coil wires as the slider was moved to

tune. One actually "tuned with the detector." The issue also noted the formation

of the Wireless Association of Pennsylvania, organized to fight the proposed Depew

Bill, which would have limited the use of the air to commercial wireless interests.

In the April, 1911, Modern. Electrics Gernsback leaped into the 27th

century with the now-classic serialized story "Ralph 124C 41+," which, intended

to give the reader a picture of the distant future, contained a considerable number

of then astounding predictions that have since been realized. Among other things,

it pictured the essential elements of radar, telling how pulsed radio waves could

be bounced off objects near and far, then to return to the sending point to reveal

the distance and direction of travel.

On April 1, 1911, it was announced that the Wireless Association of America had

reached the then phenomenal number of 11,360 members. Somewhat reluctantly, notice

was given that the cost of association buttons had to be raised to 20 cents. In

the August issue Dr. Charles P. Steinmetz, the electrical wizard, discoursed on

"Lightning Phenomena." A page ad in the October issue offered the "best Audion made

in the United States." Price complete on a wooden stand, $4. In the same issue,

Ralph 124C 41+ was seeking his sweetheart, Alice 212B 423, who had been kidnapped

and whisked away into space by a villainous Martian. Ralph was hard on the trail

of the abductor, whom he had located through his "polarized wave apparatus" or long-distance

radar - not so fantastic today as it sounded in 1911.

Early E.I.Co. catalog. These were the ancestors of Modern Electrics,

not only in name but in partial contents.

Membership buttons of two of America's oldest radio associations,

the Wireless Association of America - the world's first - and the Radio League of

America, both organized by Hugo Gernsback.

The US Naval radio station NAA at Arlington, Va., opened early in the year, and

could be heard henceforth around the world, transmitting time signals at noon EST.

On Dec. 11, the Alexander Wireless Bill had been referred to the Congressional Committee

on the Merchant Marine and Fisheries and ordered to be printed. Modern Electrics

carried the full text in the February, 1912, issue. The same issue's editorial practically

wrote a constitution for the American amateur, so closely was it followed in the

Wireless Bill as finally enacted:

Editorial

"Modern Electrics," Feb. 1912

"There should be 4 bill passed restraining the amateur from using too much power,

say anything above 1 K.W. The wave length of the amateur wireless station should

else be regulated in order that only wave lengths from a few meters up to 200 could

be used. Wave lengths of from 200 to 1,000 meters, the amateurs should not be allowed

to use, but they could use any wave length above 1.000 ..."

Wireless Act of 1912 (Section 15)

Law enacted Dec. 1912

"No private or commercial station not engaged in the transaction of bona fide

commercial business by radio communication ... shall use a transmitting wave length

exceeding two hundred meters or a transformer input exceeding one kilowatt except

by special authority of the Secretary of Commerce and Labor contained in the license

of the station ..."

The publisher announced that with the April issue the price of Modern Electrics

would be 15 cents. On April 14 the Titanic had been sunk at sea. Wireless from the

vessel brought aid and 700 lives were saved, proving the great value of the new

medium. In the April issue Clapp-Eastham announced its Blitzen tuner, and Murdock

its earphones, which, it was said, could bring in signals over 2,300 miles.

But Modern Electrics had about reached the end of a long and important

life as a publication. The last issue was published in July, 1912, and Gernsback

began to concentrate his ideas on something new, a type of publication dealing more

with the affairs of the experimenter.

The Electrical Experimenter The Electrical Experimenter

"Long live the amateur, long live wireless!" shouted the opening article of a

new publication, "The Electrical Experimenter," which had long been pondered but

finally was born with the issue of May, 1913. Gernsback had terminated a campaign

on the part of the American amateur in Modern Electrics, but he plunged

at once into the affairs of hamdom in the Electrical Experimenter by publishing

a lengthy but easy-to-read piece on "Building Large Spark Coils." He would not accept

or print advertising matter, an announcement said. The periodical - which at 5 cents

a copy was said to have been produced at a loss - would be strictly a service to

subscribers and customers of the Electro Importing Co.

The assistant editor was Harry Winfield Secor, who had been with Gernsback on

Modern Electrics, and who was destined to be a member of the organization

- with brief interruptions - to the present day.

Lee de Forest in the June, 1913, Electrical Experimenter told of "Recent

Developments at the Federal Telegraph Co." which he said "enjoyed the distinction

of having no press agents."

In the February, 1914, issue, Gernsback reported on his "Radioson" detector,

which was made by fusing a .0002-inch diameter platinum wire into a tube of special

glass so that only the most minute tip of the metal was presented to the electrolytic

solution. It was said to have been some 1,246 times smaller than the best bare-point

Wollaston wire of the day, The wireless wavemeter, one of the fundamental tools

of the art, made its appearance in the Electrical Experimenter of August.

In the spring and summer of 1915, with Europe at war, radio and electronics began

to move faster. On May 7 an SOS from the Lusitania revealed that the vessel had

been sunk by a German U-boat. Wireless dramatically had proven again its usefulness.

In the winter of 1915-16, under the aegis of the Electrical Experimenter,

radio leaders in this country formed the Radio League of America. Its purpose was

to "promote the art of amateur wireless telegraphy and telephony in the US ... to

make available to the Government a complete list of US amateur stations ... pledged

to serve the country in time of national danger or need ... "

First drawing of radar equipment appeared in Modern Electrics

in 1911, to Illustrate a science-fiction story.

There was plenty of opportunity for the magazine to take part in the country's

service, and it carried on a campaign to educate the public - and the Government

- to the dangers posed to the country's neutrality by the large German stations

at Sayville, N. Y., and Tuckerton, N. J, The cover of the August, 1915, issue showed

"Sayville Wireless Receiving German War Report," and the editorial pointed out,

with examples, how simple it would be to send coded messages which would assist

German U-boats to sink enemy (and neutral) shipping.

In the very next issue of Electrical Experimenter came the news that

the Government had closed the station at Sayville, later reopening it with a full

Government staff, Charles E. Apgar, wireless amateur of Westfield, N. J., had recorded

Sayville's messages on wax records and turned them over to Federal authorities for

decoding. These, when played back, furnished sufficient evidence to cause the Government

to close the station.

Meanwhile, the part played by the magazine aroused sharp resentment from the

old Sayville officials. Dr. K. G. Frank, head of the station, wrote a bitter letter

to the editor, the point of which was a little blunted by the fact that by the time

it was printed, the Government had already closed Sayville. Dr. Frank, incidentally,

was later convicted as a German Intelligence agent.

By this time Electrical Experimenter (it was in the spring of 1917)

was carrying a few ads - the de Forest "Oscillion" for $60, Pacific Laboratories

displayed and described double-end vacuum-tube detectors. Crystal detectors were

still in the literature of the day, but many realized they were on the way out.

An editorial on "War and the Radio Amateur," stated that the huge backlog of amateur

operators could be inducted into the country's service at a moment's notice. "What

other country could provide such a vast army of well-trained and intelligent men

as this, whose very multitude is a priceless protection?"

Then on April 6 the US entered the war and President Wilson signed the order

silencing the amateurs for the duration. Many, forthwith, went into the armed forces

as an outlet for their activities. Gernsback promptly gave vent to his imagination

in an editorial on the possibilities of "Shooting with Electricity," or magnetism,

to be more exact. Thereafter, Electrical Experimenter explored many facets of the

expanding use of electronics in warfare.

But for the Electrical Experimenter and its merchandising associate,

the Electro Importing Co., a crisis was at hand. Its business - and inventory -

has been increasing since 1908. Now President Wilson clamped down on the sale of

radio equipment. There was a war on. With a fortune in parts on hand, there was

no one to sell them to. One of Gernsback's first acts was to assemble simple telegraph

outfits. He sold thousands, but this did not take care of the great bulk of apparatus

on hand.

Then one night he stayed in the factory till 2 am, "rummaging over all the parts

in the shop." Suddenly came the solution to the dilemma. He would assemble sets

of lamps, batteries, keys, phones and other electrical components into a neat little

box called "The Boy's Electric Toys." Sitting up late several nights, he compiled

a 32-page profusely illustrated booklet of "100 Electrical Experiments" that could

be performed with the outfit. This little publication may well have been the most

important one the organization ever printed. With its aid the shelves were cleared

and the day saved for the E.I.Co. and, of course, Electrical Experimenter.

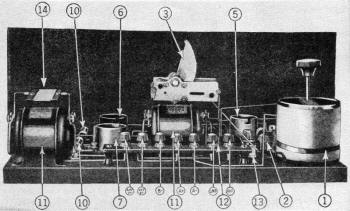

The amateur station of Charles Apgar. Equipment with which the

Sayville wireless messages were recorded may be seen at right.

The editorial of January, 1919, was titled "Electric Music." It predicted telephone

receivers covering every audible tone, with almost any required amount of loudness.

Thus was anticipated the current world of high fidelity, the loudspeaker without

a horn and the high-power amplifier to drive it. Even electronic or "concrete" music

was predicted.

In the February, 1919, issue, Electrical Experimenter began a series

of articles titled "My Inventions" by Nikola Tesla. To persuade the great Tesla

to write his own autobiography was no mean feat, and the editor still looks back

on it as his greatest journalistic beat. The series ended in the May issue, with

the author stating confidently that his proposed system of wireless transmission

of power, temporarily defeated, would finally become a "triumphal success."

With the war over, the question of "regulating the amateur" came up again. The

65th Congress proposed to amend the Alexander Wireless Bill, but the proposed amendments

forbade so many things essential to the amateur that the editor was moved to lampoon

the bill in a bitter cartoon in the February Electrical Experimenter. The bill was

killed. The hated demon had been effectively exorcised by :he power of the cartoonist's

pen and of the printed word.

The Acting Secretary of the Navy announced that, effective April 15, 1919, all

restrictions were removed on radio receiving stations other than those used for

reception of commercial traffic.

Radio News

is born Radio News

is born

The opening of the broadcast era was at hand, and the Electrical Experimenter

wrote of this and other marvels to come, in the January, 1920, issue. Among this

bewildering maze of wartime inventions and discoveries, none was more dramatic in

operation than the radio compass, described by Pierre Boucheron. It used a large

Kolster coil or loop rotated by a handwheel to which was attached a compass card.

Fixed below was a pointer to indicate degrees, hence the bearing of the ship transmitting

the signal.

A communications receiver, with regeneration, as used by amateurs

about 1916.

In July, 1919, Gernsback had begun a new publication, Radio Amateur News,

It was his first strictly radio publication, "the logical outcome," he went on editorially,

"of many attempts to put out a purely radio periodical, independent throughout and

devoted to American Radio Amateurism." He explained that in 1908 he had started

the "first magazine in America-Modern Electrics - in which many radio articles

appeared, but radio amateurism then being in its infancy could not support a purely

radio magazine." For that reason Modern Electrics devoted about one-quarter

of its content to radio. Then came the Electrical Experimenter in 1913,

"which had been more prominent than any other on account of its very important radio

section. Even during the war, with amateurism dead and nearly every radio magazine

discontinued, Electrical Experimenter at great financial loss continued

radio articles uninterruptedly, month after month, to keep alive the radio spark

in the hearts of our amateurs."

But with the war won and a new law defeated that would have killed amateurism,

he wrote, "we will witness the most wonderful expansion the radio arts have ever

dreamed of. I predict an astounding growth in the next 10 years."

Electrical Experimenter had, for some months, been carrying on its cover

a second title - "Science and Invention." In August, 1920, Science and Invention

became the official name, leaving Radio Amateur News to cover prac-tically

all the wireless material formerly handled by it. Electrical Experimenter-Science

and Invention carried tremendous prestige and was immensely useful. During

its life - till 1929 - it was virtually the electrical and experimental bible for

countless youngsters and grownups - the primary stimulus for many a future career.

The famous "Verboten" cartoon, said to have been an important

factor in defeating the amended Alexander bill, which would have destroyed amateur

radio as we know it.

The October, 1919, Radio Amateur News carried a stop-press bulletin

that "all restrictions on amateur radio are removed," and a longer mention appeared

in the November issue. The world of the ham operator would resume its pre-war status

under the Department of Commerce.

Inspired by the great possibilities of remote control of all kinds of systems

by radio, the June, 1920, Radio Amateur News pointed out that "vast fields

remain to be tapped in this category." The work of John Hays Hammond Jr. in this

new field, the editorial stated, mystified those who watched torpedoes and small

craft maneuvering without visible means of control. Radio, of course, was doing

it, by transmissions from hidden shore stations. After June, 1920, the word "Amateur"

dropped out of the name, and the magazine became simply Radio News.

In April, 1921, a full-page ad announced Cunningham power tubes, type C-302,

5 watts output, price $8. Incidentally, RCA Radiotrons UV-200 and UV-201, the "best

detector" and "best amplifier," sold for $5 and $6.50, respectively. The first annual

Amateur Radio Show and Convention was staged at New York's Pennsylvania Hotel Roof

Garden.

The first religious broadcast came over KDKA from the Calvary Episcopal Church,

Pittsburgh, on Jan. 2, 1921. The 200-kw Alexanderson alternator went into service

at Tuckerton, N. J., the same month. KDKA carried the first boxing match - Johnny

Ray vs Johnny Dundee, on April 11, and that station also broadcast the first theatrical

performance from the Davis Theatre May 9.

In an experiment conducted early in 1922 at the request of the Italian Government,

a portrait of King Victor Emmanuel was transmitted by facsimile equipment devised

by Dr. Arthur Korn. Dr. J. H. Miller of the Navy's Radio Research Bureau devised

a radio-frequency amplifying system with a range of 800 to 20,000 meters (375 to

15 kc), "with some gain as low as 150 meters" (2,000 kc ) .

Attending church with a crystal set in the early 1920's. Bettmann

Archives Photo

The famous Amrad Basketball variometer was advertised - $6.50 to $11.50. General

Radio of Cambridge, Mass., put a quality audio transformer on the market - $5. Magnavox

got out an 18-inch gooseneck horn dynamic loudspeaker - $85; "for those who wish

the utmost."

Broadcast stations on the air by August, 1922, reached 227 and, by December,

569 Radio News reported. Major Armstrong announced his superregenerative

circuit on June 28. By August, WEAF, New York City, was sending from the Telephone

Co. Building in lower Manhattan. That same month it broadcast the first sponsored

program ever put on the air - 10 minutes for $100 - sponsored by the Queensboro

Corp., to sell real estate.

Networks begun Networks begun

January of 1923 saw the first "network" broadcast, a 3-hour hookup of WEAF in

New York City and WNAC in Boston. Dr. J. A. Fleming, the great British inventor

of the Fleming valve rectifier, began a series of articles in February. It was titled

"Electrons, Electric Waves and Radio Telephony."

It was a period of great concept and invention. Prof. Louis A. Hazeltine described

his soon-to-be-famous Neutrodyne, based on a mathematical principle, to the Radio

Club of America. An editorial in the August, 1923, issue pointed out the tremendous

field of research open to the radio amateur on waves between 1 and 10 meters, "where

static almost vanishes, and new and unsuspected phenomena await the experimenter."

Some 600 variable condensers were on the market at one time in that period. All

had to bear the label "low-loss" or they wouldn't sell. Louis Gerard Pacent created

one of the first of the new order of inductances. He called it the "duo-lateral"

and pronounced it the most efficient ever.

On the cover of Science and Invention in November, 1923, Gernsback showed his

Osophone, the first bone-conduction device with which the deaf could hear through

the teeth.

Another invention ("the only patent that ever brought me in any money") was filed

for patent on Sept. 27, 1923. It was a variable condenser, comprising " ... a condenser

plate, secured on the base ... and a cooperating resilient plate ... means for flexing

the resilient plate." In clearer language, it was the compression capacitor, now

used almost universally as a trimmer, to track the sections of a variable capacitor

gang. The device was sold to Crosley and was used as a "book condenser" in the Crosley

Trirdyne receiver.

Patent drawing of the compression capacitor; prototype of today's

trimmers.

In Radio News in December, he advocated a "single-knob control" for

radios, adding that "one of these days" we will tune in with one knob ("and possibly

an additional one for volume") and get along without all the multi-control paraphernalia

of the usual receiver of the day. He had visited the television laboratory of C.

Francis Jenkins and called what he saw there the "most marvelous thing of this age."

Crude television, but impressive then.

Maj. Edwin H. Armstrong had brought back from his wartime service in the U.S.

Army in France an unusual receiver called the superheterodyne. It outshone all others

for sheer sensitivity and selectivity. Those who dared could buy the diagram and

parts and build one of these "supers" - if they had the skill, patience, time and

sheer luck. This was the heyday of the hookup, and Radio News published

accounts of them all. Experts and nonexperts built the Reinartz, the super, the

Autoplex, the Solo dyne, the Neutrodyne and scores of others that caused sleepless

nights to thousands of tinkerers. Even Radio News had its pet circuit,

called the Ultradyne, and told the story of its development in February, 1924. It

was an improved superhet, devised by the associate editor - Robert E. Lacault -

and gained wide popularity.

The oscillating tube appeared in a new role - a producer of music - with the

Staccatone, conceived by Gernsback and developed for him by Clyde Fitch. It consisted

of a Hartley oscillator with a large tapped inductance consisting of several 1,500-turn

honeycomb coils. The instrument's keys were connected to the taps, and two large

capacitors could be switched in to increase the range. It was used as a 2-note interval

signal on WRNY (a very useful device at a time when a station might be silent a

few minutes between selections without announcement or' apology) and was apparently

the first interval signal to be used so. The musical 16-note instrument had been

heard on the air before - over WJZ in November, 1923, and had been demonstrated

in conjunction with an orchestra under the direction of Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld. Its

construction was described in the March, 1924, issue of Practical Electrics.

In May, 1924, H. C. Harrison of Western Electric Co. received a patent on the

electrical recording of sound, greatly increasing the tonal quality of the phonograph

record. Western's sister company, Bell Laboratories, worked out an improved acoustic

phonograph with an exponential horn to take advantage of the new electric recordings,

which could not be heard to full advantage on older phonographs, In March, 1925,

a contract for commercial use of the new recording method and the new phonograph

was signed with the Victor Talking Machine Co., and in November the new Orthophonic

line of phonographs and the new records were put on the market. At practically the

same time, Brunswick offered an electrical phonograph; the Panatrope, with a pickup

designed and manufactured by General Electric, in which records could be played

through an amplifier, an improvement even on Victor's new acoustic Orthophonic system.

Major Armstrong and his superregenerator, with its 1200- and

1500-turn honeycomb coils.

The humble beginnings of pioneer station KDKA in the upper story

of Dr. Frank Conrad's Wilkinsburg, Pa., garage, near Pittsburgh.

Brown Bros. Photo.

A regular 6-city broadcast network was set up with WEAF as the key station in

October, 1924. It had increased to 12 cities by the spring of 1925. Thus was networking

firmly established.

Other publications Other publications

During the '20's, when it was hard to supply all the information needed in the

new art, new publications were welcomed and read avidly. Beside the Experimenter,

Gernsback published an annual Radio News Amateur's' Handibook, which ran

from 1923 to 1929, and Radio Review, "A Digest of the Latest Radio Hookups," ran

from 1925 to 1927, when the hookup craze had started to die down. Radio Internacional,

which was Radio News in Spanish, ran through 1926 and 1927. Radio Listener's Guide

and Call Book was published in 1927 and 1928 as a quarterly, giving broadcast stations

and shortwave transmitters. There was also the Radio Program Weekly around 1927

- the only weekly ever published by the organization. Television, the world's first

TV magazine, came out in two annual issues - 1927 and 1928. Later, in 1931 and 1932,

a bi-monthly, Television News, was also to be the only television magazine of its

time.

Books as well as periodicals were also in demand. The organization had been printing

books since 1910, when the first call book of amateur stations was printed under

the sponsorship of Modern Electrics. The Electric Library, whose second publication

was the one-time famous The Wireless Telephone, published from the earliest days.

During the Electrical Experimenter period it gave way to the Experimenter Library,

a title that proved so popular that it was revived in the 1920's for a new series

of books. These were usually small, stiff paper-covered works dealing with simple

radio subjects. Gernsback in 1922 wrote a larger work of 291 pages, entitled Radio

for All, which was published by Lippincott.

In November, 1921, another new magazine, Practical Electrics, was announced.

Beginners were finding Radio Amateur News a bit over their heads most of

the time, and the new magazine was slanted to "the electrically inclined layman,

the electrical professional man, the experimenter, the student and the beginner."

In 1924 the name was changed to The Experimenter, and the magazine continued

to February, 1926. It was then merged with Science and Invention, which carried

on a number of its departments for the experimenter and student.

The Experimenter of November, 1924, envisioned a military "radio television

plane" which would fly without a living person aboard. Its movement would be controlled

by radio from the ground. The plane would be equipped with "eyes" to look in six

directions at once. Miles away, and safely behind the lines of the battlefront,

the control operator would be able to inspect what was taking place in the plane's

vicinity better than an aviator in the plane could do. The radio-controlled craft

could be directed to reconnoiter, or to drop bombs on the enemy. It was a fantastic

picture of warfare then, but by no means so today viewed from the vantage point

of some 35 years of technical progress.

In January, 1925, Radio News began the story of Prof. Reginald A. Fessenden.

It was perhaps one of the most important autobiographies in radio literature. He

is credited with more than 300 inventions, without which the art today would not

be what it is. In the issue of January, 1925, Dr. Greenleaf W. Pickard, one of the

most consummate experimenters of his day, described his discovery of the oscillating

crystal, giving the credit for it to Dr. W. H. Eccles. The average Radio News

was a big periodical by now-200-odd pages in the April issue, with a monthly print

order of 400,000 copies.

The regenerative Interflex receiver, using a diode detector in

the grid circuit of the first audio tube.

There were 564 broadcast stations in the country by June, 1925, operating on

100 channels. Crowding was a big problem, but with time-sharing and geographical

separation there were channels for 550 stations. Then the broadcast band was extended

downward and 100 more channels came into use. As a result, 800 stations operated

under conditions short of ideal because high-quality transmission was being used,

and 10-kilocycle separation was not adequate for best reception. Radio News

explained the situation editorially. New sets would be made to bring in the extended

channels, but existing receivers could do nothing about it economically, if at all.

In July, 1925, Radio News launched its own broadcast station, WRNY, which

later (in 1928) achieved the distinction of being the first broadcast station to

transmit television.

Then came a new idea in radio. It was the AC tube, chronicled in Radio News

of June, 1925. A low voltage was applied to the filament from a transformer, through

terminals at the top of the tube which could be plugged into the sockets of a battery

receiver. These Kellog tubes disappeared when more advanced AC types arrived.

In Radio News of September, 1925, Gernsback described a rather unusual

receiver of his own development. It was a four-tube single-dial tuner with a crystal

in the grid circuit of the second tube, which would normally have been a grid-leak

detector. He called this receiver the Interflex and stated that his detector-amplifier

stage gave "great amplification with unusual stability of operation," The Interflex

was later improved by balancing the RF stage and in December, 1925, the "Regenerative

Interflex" was described. It had the crystal in the grid circuit of the first tube,

with a tickler coil to produce regeneration, thus combining RF and af amplification

in a single tube, with a direct-coupled diode detector.

This picture from the Experimenter, in 1924, was the first description

of military television. A remote-controlled plane was represented as being equipped

with television cameras looking in the four directions as well as up and down, and

the scenes would be projected on a six-paneled screen at general staff headquarters.

The spring of 1926 had come. "What in your opinion will be the next great development?"

the editor of Radio News was asked one day. "Undoubtedly," he replied editorially

in the May issue, "it will be the ability of man to see objects at a distance -

any distance. Why not? Through practically the same medium-radio - we hear from

all over the world!" He went on to describe television - today's television - at

considerable length, and visualized whole networks of stations operating from a

single program source, "capturing with the utmost detail all the features of a face

or landscape, with sound of highest quality."

When remarks attributed to Edison charged that "radio is a commercial failure

with waning popularity," the editor of Radio News flew to its defense,

pointing out that interest is "steadily increasing" and that "radio dealers are

now making money." Radio sales in 1926 alone would top $520 million.

The National Broadcasting Co. was formed by RCA on Dec. 9, 1926. RCA had purchased

WEAF in July, taken over its 18-city Red Network, and in December added the WJZ

Blue Network. The World Series that fall had been carried by the Blue Network, as

the Yankees and Cardinals fought it out. The Edison Phonograph Co. had released

a 12-inch disc capable of playing 22 minutes - the world's first long-playing record.

"Hello, London! Are you there, New York?" And thus - on Jan. 7, 1927 - went 2-way

trans-Atlantic voices over the first overseas radiophone service ever offered for

public use. Single-sideband transmission was used. The preliminary story on the

project had been carried in Radio News of December, 1925, and a complete report

given by G. C. B. Rowe in the March, 1927, issue.

"Can We Radio the Planets?" was the title of a Gernsback article in the February,

1927, issue. It was proposed to erect a powerful beam transmitter on one side of

the earth, bounce signals off the moon or planet, and pick up the signal at a station

on the opposite side of the earth. This forecast became a reality 19 years later

when US Signal Corps scientists first established radio contact with the moon. Interestingly,

the January, 1958, Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, in an article

"Lunar Radio Echoes," refers to this early article as the first serious proposal

to send signals to other heavenly bodies "and return."

Thus went the round of invention and development. John L. Baird, Scottish inventor,

described his television system at Glasgow, Scotland. A Washington's Birthday address

by President Coolidge was carried by a 50-station network from a joint session of

Congress. Wire television was demonstrated between Washington (D. C.), New York

and Whippany, N. J., by the Bell Telephone Laboratories. Secretary of Commerce Hoover

spoke at the Capital City and was seen and heard at this end. Later in 1927, the

Labs demonstrated color television.

"When broadcasting was established in this country," Gernsback wrote in an editorial

for Radio News of July, 1927, "the universal opinion was that it would

always be free." And thus he disposed of the question of "wired vs space radio,"

venturing that toll radio would always be a challenge to the ingenuity of builders

to overcome it and get something for nothing - the bootlegger would take what he

could.

The first "portable radio," an RCA superhet of the middle '20's.

In the November, 1927, issue of Radio News, the publisher disclosed

for the first time a new principle in receiver construction called the Peridyne.

It embodied a new method of "shield tuning" designed to bring the various RF stages

into perfect interstage alignment, hence to operate at maximum possible efficiency.

He did this by placing above the coil a metal disc that was moved up and down with

a threaded rod. The so-called "slug" or "shield" thus compensated for inequalities

in the inductance of the tuning coils, raising or decreasing the inductance in accordance

with its distance from the turns of the coils. The Peridyne principle is the first

use of nonferrous slugs or plates as tuning or trimming devices, and introduced

the service technician to the screw-adjusted trimmer.

True ac-operated sets began to come on the market in the spring and summer of

1927. RCA had announced the ac-heated 226 and 227 tubes early in 1927. By the end

of the year the AC era had arrived, and several articles in the November issue of

Radio News confirm that fact. The Columbia Broadcasting system went into

operation in September, 1927.

Radio News of January, 1928, announced that the double-grid tube had

arrived, calling it "probably the only real advancement ... since the invention

of the triode." The tube had enjoyed tremendous popularity in Europe, but had been

neglected here. Double-grid tubes had been described "for years in this magazine"

and had been used in the Solodyne, which eliminated the B-battery.

The Peridyne receiver, which introduced nonferrous trimming slugs

for coil tracking.

The electrodynamic cone loudspeaker was developed by the Bell Telephone Laboratories

and demonstrated in April, 1928. Radio News carried the news at that time

and touched on it again in November issue. The device revolutionized techniques

of sound reproduction. Twenty-one manufacturers were putting out such units by late

1928. Installed atop a New York office building, one dynamic speaker was heard three

miles away on the New Jersey shore. So great was their popularity that stores could

not get them fast enough, and reproduction was considered faithful from the lowest

to the highest tones in the range of human hearing.

"During the past few months," editorialized in Radio News in September,

1928, "a new era seems to have opened that will be known hereafter as the 'Shortwave

Cycle.''' Short waves, it was explained, are not new, having originated back in

the days of 1908 when amateurs began first to converse with each other on waves

below 200 meters with dots and dashes. Marconi, in October, 1927, speaking at the

Institute of Radio Engineers, had predicted that the short waves "are destined to

be vital in radio and television." The editorial went on: "As time passes the interest

in short waves becomes greater and greater ... It would not surprise me at all if

during the next 5 years, both sight and sound would be transmitted completely on

short waves, and the upper channels from 200 to 600 meters were abandoned completely."

The Radio News station 2XAL, WRNY's transmitter on 30.91 meters, which

had started in the spring of 1928, "had poor reception within 200 miles of New York,

but beyond that it gets better and better."

Start of Radio-Craft Start of Radio-Craft

In the spring of 1929, Radio News, Science and Invention,

Amazing Stories and associated magazines, were sold to other interests.

Radio News of April, 1929, was the last Gernsback issue. In July of the

same year he created a new magazine in the fields of the set builder, shortwave

fan, radio serviceman and amateur. He named it Radio-Craft. It would devote

itself to the experimenter and constructor, he editorialized, noting that in the

United States and Canada there were some 250,000 to 350,000 active radio enthusiasts.

Radio-Craft would not carry "re-hash stuff," but new material, "edited

first, last and always for its readers."

Under the heading "the Constructor," the first issue of Radio-Craft

carried a story about the "Supreme Power Amplifier" which had two CX-350 tubes in

the output stage. Another story was on the "Harkness Screen-Grid De Luxe." The magazine

also described the Pilot "Super-Wasp," which became one of the most famous shortwave

sets, in an article by John Geloso (now one of the leading Italian manufacturers

of electronic and hi-fi equipment). Other authors included Jack Grand, H. G. Cisin,

Clyde J. Fitch and Charles Golenpaul.

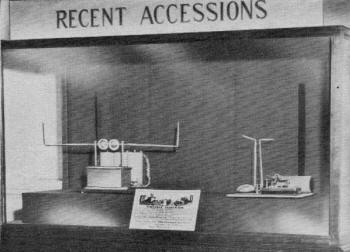

Marconi's early "microwave" equipment. Apparatus with parabolic

antenna at left is transmitter; that at right the receiver.

The permanent-magnet dynamic speaker made its appearance in 1931. It was recommended

for use with battery portables - scarcely anyone then foresaw it as the universal

speaker it is today.

In June, 1930, Short Wave Craft magazine had begun. It noted the huge

buildup of the art, which "promises to assume large proportions in the years to

come." In the June-July issue of 1931 it was reported that 7-inch waves had spanned

the 21 miles of the English Channel between Calais and Dover, and that amateurs

were blazing trails with contacts throughout the world. The boys were getting started

on channels as short as 5 meters. A 15-watter had been heard almost around the globe.

With the May issue of 1937 the publication had a new name - Short Wave and

Television (later Radio and Television), and combining the fields

of the shortwave and television experimenter, had the largest circulation of any

such periodical in existence. In the May issue, John V. L. Hogan, who then owned

and operated New York City's WQXR, wrote on "Short Wave Broadcasting." The publication

continued to dominate the radio-video field until 1941, when it was merged with

Radio-Craft.

One of the decisive tube inventions of the early 1930's was the "variable-mu"

(also known as super-control or remote-cutoff) tube. It could be biased to control RF gain gradually, hence was a highly effective device in automatic volume control

circuits. It also eliminated cross-modulation, a bad feature of earlier screen-grid RF tubes. Based on the variable spacing of grid wires, it was the invention of the

late Stuart Ballantine of Boonton, N. J.

Gernsback Publications put out an Official Radio Service Manual late in 1930,

collecting for the service technician many hitherto unobtainable schematics of the

sets he had to service. Editions followed annually, and in July, 1933, a Consolidated

Manual, combining the first three volumes. was announced. One of the most important

and valued radio documents of the day, it sold more than 80,000 copies.

Meanwhile, British tube makers had produced Catkin metal tubes, and American

manufacturers were quietly experimenting with the metal types.

In 1932 the Radio-Craft Library appeared. This was a collection of practical

radio books, some of which were made up of material from the magazine. They were

larger than most of the earlier books published by the organization, running about

64 pages. Subjects ranged from radio set analyzers to frequency modulation. The

library ran to 28 books and suspended in 1941, due to war shortages. Some of these

red-covered booklets are still to be seen in old-timers' collections. Short

Wave Craft published a number of blue books on shortwave construction and operation.

One of these, on coil winding, was so useful to the constructor that inquiries for

it are still received occasionally.

In February, 1933, Radio-Craft announced "The Greatest Set of the Year,"

a complete ac-dc receiver which could be held in the hand. The famous International

Kadette opened an age of table midgets, though its size (8 5/8 x 6 1/2 x 4 inches)

would not be startling today. Indeed, it was a three-way portable, for it could

also be used with a 6-volt (auto) battery and B-batteries! The set, incidentally,

was not a superhet-c - it had one stage of rf, power detector, an audio stage and

a small mercury-vapor rectifier which had been designed for automobile B-power units.

Radio-Craft of December, 1933, carried a feature article on an even

smaller set, called the "Kaydette," by the same company. It sported two tubes and

an indoor antenna.

A typical radio store of the mid-'20's. It was operated by United

Cigars - believe it or not. The same company had four service stations in New York

City. Brown Bros. Photo

Elaborating further on his Osophone of 1923, Gernsback described in Radio-Craft

of March, 1934, a later idea in the field, the Phonosone. It was a Baldwin balanced-armature

loudspeaker phone attached to a headphone headband and worn against the forehead,

permitting vibrations generated by the output of a radio to be transmitted to the

bones of the head, to lighten the world of the deaf and near-deaf. The Osophone

was the first description of a bone-conduction hearing-aid unit. In the July issue

was a story on a light-sensitive device worn on a strap around the neck. Equipped

with a battery and buzzer, it would help guide the sightless.

An editorial in Radio-Craft of August, 1934, noted that the television

"picture is still pitifully inadequate," going on to remark that "as long as we

cannot have an image at least a foot square of excellent detail that can be viewed

in broad daylight, it is obvious that the television set has not arrived."

Radio, meanwhile, had grown into a multi-million dollar industry - RCA alone

in May, 1935, announced plans to spend $1 million for field television tests. The

radio servicing industry had grown likewise. The July, 1935, issue announced that

"the service business has advanced to where it must now be recognized as a separate

industry, its dollar sales are in the millions." Estimates from all sources "have

established the amazing figure of some $30 million in labor costs alone in 1934."

Added to equipment costs this swelled the total to $45 to $50 millions annually.

"And this is only the beginning."

Metal radio tubes, similar to those we now have in the shops, came from American

tube makers in the middle 1930's. October Radio-Craft of 1935 carried an

exhaustive semitechnical story about their design and capabilities. Glass tubes,

then, appeared to be on the way out. However, in Radio-Craft issues of

late 1936, 16 or more new receiving tubes were pictured and described. Only one

was a true metal tube.

"Good servicemen need not be worried about the quackery practices by the so-called

'gyps' of the game," who were "outnumbered and certainly would be eliminated," editorialized

the July, 1937, issue, pointing up to present-day readers that the gyp apparently

always has been with us. The same issue reported that the Department of Commerce

had installed ultra-shortwave fan type markers to aid air traffic at landing fields.

A special, more than double-size number of Radio-Craft in March, 1938,

celebrated the 50th anniversary of radio as dated from the production of the first

radio waves in 1888 by Heinrich Hertz. It was filled with articles on the progress

of radio, its early history, memoirs of old-timers, and included a few predictions

for the future. The most striking feature was the illustrations, which depicted

radio equipment and installations from the earliest days. Numbers of the better-established

radio companies reprinted advertisements that had appeared originally nearly two

decades before. Not the least valuable contribution made by the "Jubilee Issue"

was the preservation of historical material in some of the articles and the old-timers'

reminiscences, some of which would be hard to uncover today.

The International Kadette, earliest of the true small ac-dc radios.

The best news of summer, 1938, came - television-wise - when the NBC revealed

plans to broadcast 5 hours of visual programs weekly. Pictures were 441 lines, with

a 5 to 6 aspect ratio (10 by 12 inches, said July's Radio-Craft).

Meanwhile, at the convention of the IRE, Vladimir Zworykin and R. R. Law of the

RCA Laboratories had projected pictures on an 8 x 10-foot screen.

With the July, 1939, issue 10 years of uninterrupted publication of the magazine

had been completed. Gernsback wrote: "I take this occasion to voice our heartfelt

thanks to the thousands of loyal followers of the magazine and to the large majority

of those who have read it through all these years. Radio has come a long way since

then. In 1929 we had no pentodes, no variable mu, no metal tubes, no tuning eyes,

no octal, loctal or acorn tubes, no black-and-white cathode-ray tubes that finally

made television possible."

A. P. King of the Bell Labs had demonstrated that megaphone horns could launch

15-cm waves along a wire over distances to the horizon, adding in the November,

1939, issue that the fidelity of transmission was "flat within 1 db over a bandwidth

of 250 mc," enough to carry 40 or 50 TV channels. Dr. George Southworth of the same

organization was experimenting with coaxial cables and waveguides, and told stories

about removing the inner conductor of a quartz-insulated cable without affecting

the efficiency of transmission, and then of removing the outer conductor, allowing

the microwave signals to be "conducted" by the insulating quartz alone.

By early 1940, frequency modulation had earned for itself an almost permanent

niche in the Monthly Review department, as the continuing progress in that field

was appraised. Much experimental work was going on. Major Armstrong's Alpine (N.J.)

station W2XMN had been on the air for some time. On Oct. 31, 1940, the FCC issued

the first commercial FM licenses. The December issue carried an ABC primer of FM

prepared by authorities.

FCC's special authorization for use of Gernsback spark transmitter

at 1954 IRE exhibition. Note that this 1906 equipment was well up in the vhf range.

In the issue of March, 1942, Radio-Craft carried some 30 pages devoted

entirely to what leading American radio engineers thought about FM and its future.

Major Armstrong wrote a lengthy piece. The New York Times paid a million dollars

odd for WQXR and W2QXR. The NBC had installed its FM station - W2XWG - atop the

Empire State Building. There was a station on Mount Washington, N.H. The radio map

of FM was rapidly filling up.

But most radio activity was grinding to a stop because of war duties and war

shortages. The service technician was compelled-and urged as a patriotic duty -

to keep America's receiving sets operating without new tubes or components Radio-Craft

instituted a special Wartime Radio department, beginning in the August-September,

1942, issue. Articles began to appear on servicing volume controls, RF coils and

other components formerly replaced. There was even a story on "Wartime Transformer

Rewinding" and the long series of tube-replacement articles began with "War-time

Tube Replacements" in February, 1943. Dozens of such articles - and even a few books

- were printed. The service technician became adept at substituting practically

every tube in the manual, and even repairing a few!

About this time, with the US in the middle of World War II, the ugly head of

"radio censorship" made its appearance and Wendell Willkie demanded: "Let's not

have any more of this nonsense." Radio-Craft, editorially, echoed those sentiments

in December, 1942. Dr. Lee de Forest, father of radio, had celebrated his 70th birthday

at Los Angeles on Aug. 26, 1943, and his comments on radio in general were printed

in the October issue, following the anniversary.

Nikola Tesla, possibly the greatest inventive mind of all history, died Jan.

7, 1943. The next issue of the magazine printed a complete article on the life and

inventions of the almost-forgotten genius who had given us our now-universal alternating

current, had pioneered in high-frequency, radio remote control and in power transmission

by viscosity of liquids, but had in most cases seen his patents run out long before

society was technically able to put them to work. Expressions of appreciation from

the leading figures in the electronic world indicated that more than one had cut

his scientific teeth on the Inventions, Researches and Writings of Nikola Tesla,

published in 1894.

Beginning with the May issue of 1943, the Radio-Craft cover had begun

to show the name "Radio-Craft and Popular Electronics," advertising that the periodical

would henceforth cover the ramifications of the broader field. A monthly section

headed Electronics was carried thereafter in all issues, and grew rapidly in size

and importance. One of the first comprehensive stories therein covered the evolution

of the Klystron, and a serial "Practical Electronics" had begun under the authorship

of Fred Shunaman, then associate editor.

The Age of Television The Age of Television

On August 21, 1945, the FCC lifted its wartime ban on one amateur band - 112-115.5

mc. The other bands were freed Nov. 15, permitting some 60,000 stations to resume

operation after 4 1/2 years of silence. In November, RCA announced that postwar

TV sets, priced from $200 to $450, would be available in 6 months. Other manufacturers

were following suit. By September, some 515 FM stations had been applied for, also

129 TV transmitters and 265 AM outlets.

The book-publishing division of the organization picked up in 1946 where the

Radio-Craft Library had left off. Under the title of Gernsback Library,

a number of smaller paper-covered books were printed. Starting in 1951 with Frye's

Basic Radio Course, larger, cloth-bound editions were printed, with such excellent

results from the viewpoints of both publisher and reader that smaller books were

dropped almost entirely, and only full-length works printed, though they can still

be obtained in paper-covered as well as cloth-bound editions.

Large-screen television of 1939. The tube stands upright, projecting

an image upward to a mirror on the slanting cabinet lid, from which it is reflected

to the viewing screen.

The 40th anniversary of the invention of the vacuum tube by Lee de Forest was

marked by a special issue of Radio-Craft of January, 1947. The inventor

was then 73 and still inventing. Articles by de Forest himself, Frank E. Butler,

his chief aid during the inventive years of the early 1900's, and others who remembered

or were associated with the birth of the Audion, were included.

Radio-Craft in January, 1948, published its first Special Television

Number. It was the first of 10 annual television issues, the earlier ones of which

especially filled a need for detailed and consolidated information which could not

be obtained elsewhere. The special TV issues were discontinued only when such information

became general and easily available.

On June 30, 1948, the Bell Telephone Laboratories announced and demonstrated

the transistor, a crystal that could amplify an electric current like a vacuum tube.

The discovery was heralded throughout the world and was the subject of a feature

article "End of the Vacuum Tube?" in the September issue. Treating the coming of

the transistor later (in the January issue of 1949), Gernsback declared: "It will

play an increasingly important role in the future. When we look back at the humble

beginning of the crystal detector, we marvel at the spectacular comeback it has

made in the form of the new transistor, destined some day to supplant the vacuum

tube."

Late in the spring of 1948, a letter had been addressed to the older subscribers

by the publishers. The name Radio-Craft no longer seemed to be the proper

name for a publication that had so much to do with the modern world of electronics.

"Would the readers suggest a new title?" And so Radio-Craft, at the end

of 20 years of existence, became Radio-Electronics with the issue of October, 1948.

Gernsback promised that the publication would ever be in the forefront of radio-electronic

happenings the world over.

One of the first articles in it was about the new LP microgroove phonograph record

announced by CBS and Columbia Records to the newspapers in the spring of 1948 and

discussed subsequently at technical meetings.

- Gernsback Electronic Publications 1908-1958 - Modern

Electrics - 1908-1912 - Electrical Experimenter (Science &

Invention ) - 1913-1929 - Radio News -1919 - Practical Electrics

- 1921-1924 - Radio News Amateurs' Handibook - 1923-1929 - The Experimenter

- 1924-1926 - Radio Review - 1925 - 1927 - Radio lnternacional (in Spanish)

- 1926-1927 - Radio Questions and Answers - 1926-1929 - Radio Program Weekly

- 1927 - Radio Listener's Call Book - 1927-1928 - Television - 1927 - 1928

- Radio Dealer's Personal Edition Radio News - 1928 - Radio-Craft

(now Radio-Electronics) - 1929 - Television News - 1931 - 1932 - Short Wave

Craft - 1930 - 1936 *Short Wave and Television - 1937 - 1938 *Radio and Television

- 1938 - 1941 *The name Short Wave Craft was changed to Short Wave and Television

in 1937, and to Radio and Television in 1938.

Radio waves had long been directed through the air and carried over wires, and

much experimenting had been done with more advanced methods of guiding those of

ultra-high frequency. In its December, 1948, issue Radio-Electronics told

the story of the microwave guide, which channeled the uhf waves like water through

pipes. This was a project of the Bell Labs at its Holmdel, N. J., field laboratory,

based on pioneering work done for years by Southworth and others. The work is still

going on at Holmdel - with round guides - and is considered one of the most promising

fields of research for the future of long-distance communication.

Television was getting into high gear in the spring of 1949. "When broadcasting

began in 1920 it engendered the first major radio boom, but now we are in the middle

of another similar cycle," commented Radio-Electronics editorially in March.

"This time it is television that is gaining rapid momentum. The difference is that

the present boom will make the first look small by comparison." As of Jan. 1, the

editorial pointed out, only 1,037,000 homes were TV-equipped and the public had

paid some $432,429,000 for sets. Authorities had predicted that in 1949 the public

would own a minimum of 2 million sets at a cost of some $650 million. "All in all,

it will be seen that television will enrich our economy by $1 1/2 to $2 1/2 billions

at least."

By Jan. 1, 1950, 98 TV stations were operating in 24 cities. Noting TV's advantages,

the Navy had begun to use it in teaching.

The January, 1948, issue had carried a short note on the American Telephone &

Telegraph Co.'s plans to connect New York and Boston telephone-wise by microwave.

Experimental transmissions had been made as early at Nov. 13, 1947, with Washington

hooked in by coaxial cable. On May 1, 1948, this circuit was inaugurated as the

Bell System Eastern Network. A Midwestern network opened Sept. 20, and on Jan. 11,

1949, the Eastern and Midwest networks were linked, extending the system from the

East Coast to St. Louis. Sept. 4, 1951, saw the beginning of coast-to-coast television.

Radio-Electronics reported in October, 1949, on a new lightweight printed

circuit introduced in the Telex model 200 hearing aid. It was some 1 x 2 inches

in size and with all components weighed 1 1/16 ounce. How to build a see-in-the-dark

Snooperscope with war-surplus materials was described and pictured in the same issue.

Radio-Electronics noted in December, 1950, that the FCC had picked the CBS sequential

color TV system as standard for the country. It had been tentatively approved on

Sept. 1, but now was finalized and commercial broadcasting had begun Nov. 20. An

estimated 7 million sets then in the public's hand would need an adapter to tune

in the programs correctly and convert to color - the cost per set: $125 to $150.

Calling the FCC decision a "bombshell" to the TV industry, Gernsback editorially

called it "Choleric Color TV," stating that "color television should be allowed

to develop naturally," just as radio did. "To use forceps to force a premature birth

may mutilate the color TV child for life." And most of the TV industry agreed.

"Electric Spaceships" was the subject of an article by the German rocket expert,

Prof. Hermann Oberth, who touched on the use of electrical repulsive forces to drive

the rocket into space. It ran in the December, 1950, and January, 1951, issues.

Once free of the earth's atmosphere, he went on, "we can then build machines which

collect energy from the sun ..." At the time the article was considered almost fantasy

(but fantasy backed up with rigid mathematics) and even Gernsback would scarcely

have dared to predict that by 1957 we would have a space vehicle in flight.

Phonevision, the first proposed toll TV system, was advocated by Zenith. Subscriber-Vision,

engineered by Skiatron, had also been undergoing tests over New York City's WOR-TV.

The picture was given an electrical "jitter" by the transmitter in both these systems.

It could be taken out at the home receiver by a call to the phone operator or by

inserting a special card key that introduced a correcting voltage.

By May, 1951, television and the various subjects associated with it were occupying

a clear majority of the pages of the magazine. Ultra-high frequency was the keynote

of the national IRE convention summarized in the June Radio-Electronics. In the

same issue it was announced that Western Union had organized a television service

outfit. Opening shop first in New Jersey, it would handle Du Mont installations

and do service work in several counties at rates commensurate with Du Mont's regular

charges. Radio-Electronics treated the topic editorially in the July issue. Conclusion:

Western Union "has still to learn the business, and that they cannot do overnight."

The furor subsided.

Oldest member of the staff Oldest member of the staff

One of the oldest members of the staff is the invisible Martian office boy, Mohammed

Ulysses Fips, who in the early days of Modern Electrics had his own department,

The Martian Spark. Now, grown to a grave and long-bearded consultant, member of

many learned societies with unheard-of name, he confines himself to the description

of one wonderful discovery a year, usually in the April issue. These range from

a radium-operated one-tube receiver, so powerful that it needs a throttle rather

than a volume control, to a means of keeping an office quiet by picking up the noise

with a microphone, amplifying it and reproducing it at equal volume, but opposite

phase, to the original sound. Thus complete silence would result. Fantastic, when

published, but patented within 2 years by one of the country's greatest acoustic

researchers. Other ostensible April Fool stories were trial balloons, stories of

things a little too far-fetched to be predicted with confidence, but which might

or should be invented. Such was the Westinghouse 1933 vest pocket receiver, so ridiculously

small for the time as to arouse the indignation of engineers, but a clumsy and bulky

set by today's standards, or Electronic Brain Servicing, screamingly funny in 1950,

but quite serious when described in July, 1956, as manufactured by Lavoie Laboratories.

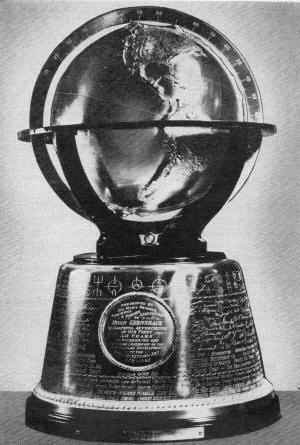

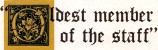

The silver tribute awarded to Hugo Gernsback by the radio-electronics

industry in 1953.

"A radically new type of teaching now becomes possible," Gernsback editorialized

in the September, 1951, Radio-Electronics. Television had now made many

things possible that were not easy before. With television in all public schools,

wired with a city TV Education Center, 50 brilliant teachers could reach the city's

800,000 students, whereas, with the usual system, 35,000 teachers were needed.

An editorial in the November, 1951, issue pointed out that "the radio-electronics

industry will soon be one of the top three" in the country, ranking next to steel

and aircraft production. More than $7,600,000,000 in electronic contract's will

have been awarded by the year's end, Dr. Allen B. Du Mont reported.

Tape recording, a new field of the electronics industry, had been growing rapidly.

In the August, 1952, issue it was noted that newspaper opinion held that a "revolution

was taking place in the science of capturing and reproducing sound" and was being

used widely in many fields - entertainment, business, education and professional.

The January, 1953, issue - the sixth annual television number - noted editorially

that as the issue went to press "the first closed-circuit telecast of the Metropolitan

Opera was about to be carried to a number of theaters.

In April, 1953, Gernsback predicted that "intercontinental TV programs are feasible."

He added that the idea was not original with him - Baird had actually bridged the

ocean with images as early as 1928 but with low frequencies - present-day TV used

high ones. It would be necessary "to build many relay stations to skip from island

to island" over any large bodies of water. Where natural islands were not available,

"iron islands" in the form of steel caissons are advised for the relays.

In the April issue there was also an article on a new German electrostatic speaker

- not a new idea exactly, but a new design. In June, the editorial told of a new

"booming field for video-closed-circuit television," which, the editorial went on,

"is certain to rise in the next 10 years to unimagined heights." Du Mont had produced

three-dimensional or stereoscopic TV for use in atomic research.

In May, 1953, several hundred leaders of the electronics industry awarded the

editor and publisher of Radio-Electronics, at a Radio Industry Banquet

in Chicago, a trophy, a large sphere cradled in rare metals, mounted atop a handsome

silver base set in ebony. The whole stands 27 inches high. On it were engraved the

names of his many friends and associates (33 firms and 97 individuals) who contributed

to the award, as well as the names of 75 living and dead "immortals" in the field

of electronics.

Part I of a series of special articles on "High-Quality Audio" began in the September,

1953, issue. An important -feature of the series, it was said, would be to go beyond

the purely technical details and treat the subject as an extension of the art of

music in general, as one would like it in the home. Richard H. Dorf was the author.

The FCC, which had granted a limited tentative approval to the NTSC compatible color

TV system in midsummer, now brought the year to a happy close by granting full approval

on Dec. 21, thus opening the door to our present system of color TV broadcasting.

Use of the G-Line, invention of Dr. Georg Gobau of the U.S. Signal Corps, was

described as an ideal facility for long uhf-TV transmission lines in the March,

1954, issue. The pros and cons of "High-Fidelity Loudspeakers" were discussed in

this and subsequent issues by the British authority, H. A. Hartley. The August issue

carried a Bell Laboratories story on the solar battery, which operated a small transmitter

and was the first practical attempt to obtain real electrical power from light.

About the Author

To prepare an article of this type required an unusual combination

of qualifications - expert knowledge and wide experience in the fields both of journalism

and electronics, Radio-Electronics found this combination in Tom Kennedy, recently

retired associate radio editor of the New York Times. His acquaintance with radio

goes back to 1907, when as a high school student he assembled a crystal set from

parts bought from the E.I.Co. (following it up the next year with a 12-inch spark).

He studied electrical engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh,

then worked on radio compasses, first as Radio Compass Officer in the Navy (World

War I) and later as civilian employee, installing equipment on more than 50 destroyers

and a dozen land stations. He was radio editor of the Pittsburgh Post and Sun and

technical radio editor of the Philadelphia Evening Ledger before joining the Times

in 1927. Since his retirement Mr. Kennedy has done some consulting work in high-fidelity

(his activities in the high-fidelity and amateur recording field were the subject

of an article in Fortune, October, 1946) and free-lance writing in electronics and

kindred fields.

"'How foolish we once were,' our children will say in future, 'to allow our great

scientists to speak to only a few dozen, or perhaps a few hundred pupils when the

great man could lecture to 500,000 at the same time,' " Gernsback editorialized

in the February, 1955, Radio-Electronics on the topic of "Tec-Teleducation,"

the substance of which he had proposed as far back as December 1950 in "Newspeek,"

a prognostic spoof on the times. "Fortunately," he went on, "we have in our hands

today the means of making Teleducation a reality in the immediate future ... Just

as we have a national closed-circuit TV network, there will be a similar one for

grade and high schools, colleges and universities, covering the entire country ...

Teleducation will not displace our teachers - it will supplement and augment them."

More than 42,000 radio engineers registered at the 1955 national convention of

the Institute of Radio Engineers. Ultrasonics was one of the chief subjects. It

drilled teeth painlessly and was useful in internal diagnostic work. RCA exhibited

a new tri-color vidicon tube, and Du Mont displayed the Iconumerator, which counted

a million small objects in the twinkle of an eye.

In the August Radio-Electronics was a story of reliable TV "scatter"

communication over 188 miles between Holmdel, N. J., and the Round Hill station