|

June 1957 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

This "Harmonic Analysis Made

Easy" article from a 1957 issue of Radio-Electronics magazine presents

a brilliantly clever graphical method for performing harmonic analysis without complex

mathematics or the aid of a computer. By breaking down a waveform into discrete

ordinates every 30 degrees, the technique transforms Fourier analysis into a manageable

visual process, and skipping the messy math. Author Arthur Shulman's approach is

particularly ingenious in how it handles vector addition: plotting each ordinate's

value at its corresponding phase angle on a vector diagram automatically accounts

for trigonometric multiplication. The resultant vector's length and direction directly

reveal the harmonic's amplitude and phase. This method makes visualization remarkably

simple even without computational aid. By constructing vector polygons, engineers

could approximate a square wave using its fundamental and third harmonic components

(although a true square ware contains an

infinite number of odd

harmonics),

achieving practical accuracy for most applications. The graphical representation

turns abstract mathematical concepts into tangible geometric operations, allowing

the decomposition of complex waveforms using only drafting tools.

Harmonic Analysis Made Easy - Analyze harmonics without

higher mathematics

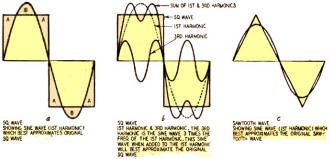

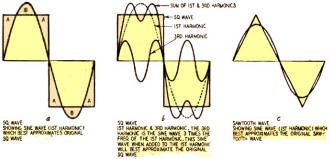

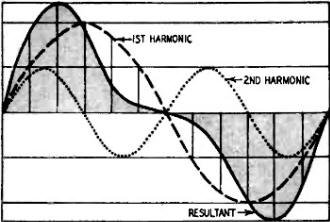

Fig. 1- Waveforms and their sine-wave approximates.

By Arnold R. Shulman

Most of us, while watching a waveform on an oscilloscope, have wished we could

measure the harmonic content. Many of us know that the harmonic content of any wave

can be determined by Fourier analysis. The trouble is that Fourier analysis requires

a knowledge of higher mathematics. Fortunately there is a method for determining

the harmonic content of a wave without using higher mathematics.

Sine waves have been adopted in engineering as the fundamental waveform. Sinusoidal

voltage is the only voltage waveform such that, when applied to a resistance, inductance

or capacitance, the current will have the same waveform. By using the sine wave

as a reference, a waveform can be analyzed into a number of sine waves of different

frequencies. This is Fourier analysis.

These sine waves of different frequencies are called the first harmonic or fundamental,

second harmonic, third harmonic, etc.

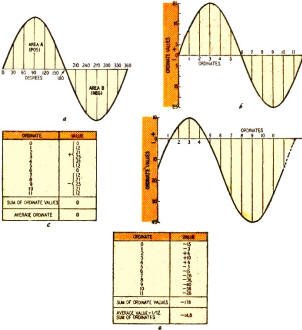

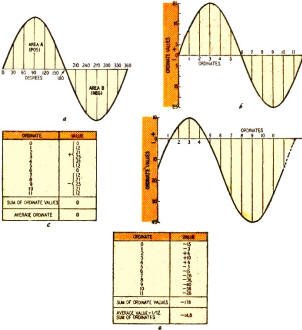

Fig. 2 - Sine waves with their ordinates and ordinate values

charted.

Fig. 1-a shows a square wave. It doesn't look anything like a sine wave,

but the figure shows that a sine wave can be drawn to approximate it. The sine wave

that will best approximate this square wave will have a definite phase and magnitude

with respect to it. This best-fitting sine wave is the first harmonic. If the square

wave is to be applied to a circuit, its effects may be calculated by assuming that

the first-harmonic sine wave was applied and by doing the calculations based on

that waveform.

Practically all formulas used in electrical engineering are based on sine waves.

Most instruments are calibrated for them - a square wave would cause the average

multimeter to read 11% high. The ability to approximate any wave with sine waves

is extremely important.

Actually the first harmonic is a poor approximation of the square wave. The shaded

areas A are not included, and area B is outside the square wave. The next step is

to find a sine wave of another frequency which, when added to the first harmonic,

will more closely approximate the square wave, adding to the areas marked A and

subtracting from the areas marked B. The third harmonic (a sine wave three times

the frequency of the first harmonic) will do that (see Fig. 1-b). If appropriate

higher harmonics were found and added to the first and third, a closer approximation

would be found.

It is evident that the first harmonic is a good approximation of the saw-tooth

wave in Fig. 1-c. It could be used in many calculations without introducing

a significant error. However, Fourier analysis permits any continually periodic

waveform to be represented and measured.

Graphic Analysis

The graphical procedure which follows is a close approximation to the accurate

mathematical solution (see equation at the head of this article). It is particularly

important because in most practical situations it is necessary to find only a few

harmonics. The higher-frequency components are usually so small that they have little

effect.

Fig. 3 - Vector diagram of a square wave and method of construction.

The first term of the equation is A0, the dc component of the wave.

Fourier analysis can of course be used to analyze a waveform with no dc component,

such as the sine wave of Fig. 2-a. In this wave, a voltage (or a current, if

you like) starts from zero and reaches a positive maximum in 90°, one-quarter of

a cycle. In the next quarter it drops to zero and in the third starts in the other

direction and reaches a maximum. In the last quarter it drops to zero and is ready

to start all over again.

To analyze the wave, we set up a number of ordinates, evenly spaced along the

cycle, to give us its value at the instants the ordinates represent. (We say "value"

because the curves may represent voltage or current.) In our examples ordinates

are placed every 30°, giving 12 ordinates a cycle. For greater accuracy more ordinates

- say one every 10° - could be set up, but every 30° is enough for most wave-shapes.

We number our ordinates from 0 to 11 (ordinate 12 is ordinate 0 since it starts

the cycle again). The table, Fig. 2-c, is then made. To find the average ordinate,

representing the dc value of the wave, we add all the values and divide by the number

of ordinates. In this case, the average value is zero, as is the case with all symmetrical

ac sine waves. Fig. 2-d shows a wave of exactly the same shape as 2-a or

-b, but with a different zero axis. Most of this wave is negative. Fig. 2-e

shows that the dc component of the wave is -14.8. This is the value a dc meter would

indicate. The next step is to determine the magnitude of the first harmonic. Mathematically

this is represented by A1, Sin x ÷ B, Cos x where

Graphically this means, to find A1, take the sum of the ordinates

each multiplied by the sine of the angle at which it occurs, and divide by half

the number of ordinates used. To find B, take the sum of each ordinate multiplied

by the cosine of the angle at which it occurs, and divide by half the number of

ordinates used.

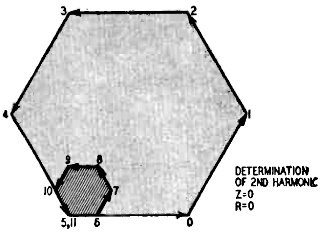

Let us work with the square wave of Fig. 3-a. The 360° are divided into

12 intervals and the ordinate length determined. The table (Fig. 3-b) is then

made. Next the respective ordinate values are placed end to end in a vector polygon

(see Fig. 3-c) with each ordinate placed at the angle it appears in the cycle.

This takes care of the multiplication by the sines and cosines of the respective

angles at which the ordinates occur.

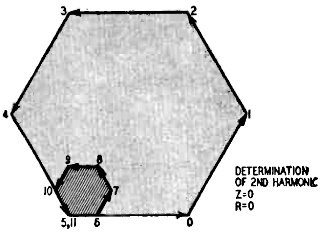

Fig. 4 - Vector diagram of a square wave's second harmonic.

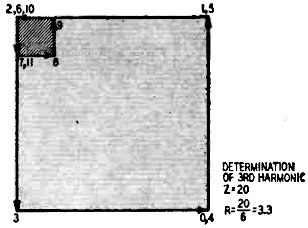

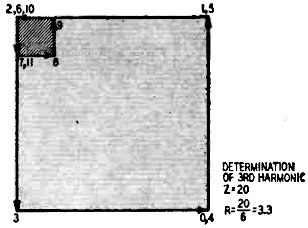

Fig 5 - Vector diagram of a square wave's third harmonic.

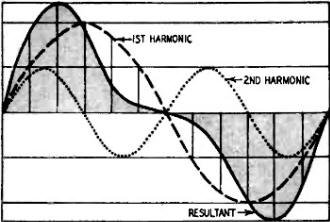

Fig. 6 - Fundamental, second harmonic and resultant frequencies.

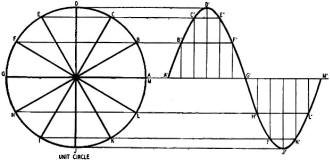

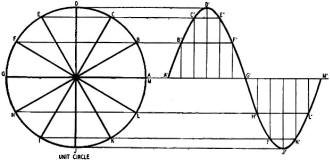

Fig. 7 - A unit circle used to construct a sine-wave drawing.

Table I - Determining Components of Waveforms (values taken from

Figs. 3, 4, and 5)

Computing Resultant Vectors

The resultant vector Z, drawn from the point of origin to the end of the last

of the ordinates, gives the total value of all the vectors and can be analyzed in

terms of its component vectors. The sum of the ordinate (vertical) values of these

is equal to the vertical value of the resultant. The sum of the abscissa (horizontal)

values of the vectors is equal to the horizontal value of the resultant. Each vector

value in the table (Fig. 3-b) times the sine of its respective angle gives

the ordinate value (A1) and each of them multiplied by the cosines of

their respective values gives the abscissa value (B1).

If the vectors do not terminate at a point on the line OB of Fig. 3-c, this

displacement is found by drawing a line from the origin (0) to the terminating point

and measuring the angle between the two lines clockwise from OB. This angle is the

phase displacement in degrees from the origin (Fig. 3-d) .

The second and third harmonics are found by drawing graphs similar to those of

Figs. 3-b and 3-c. Since the second harmonic is twice the frequency of the first,

it will go through 60° while the first harmonic goes through 30°. Thus the ordinates

are drawn at a 60° angle to each other, as in Fig. 4. The third harmonic is

three times the frequency and the quantities are 90° apart, as in Fig. 5. Measuring

our resultants, we find that the first harmonic vector is 74.6 units long, making

its value 12.4 (1/6 of 74.6). The second harmonic is zero, and the third harmonic

is 1/6 of 20, or about 3.3, in phase with the first harmonic.

So far we have dealt with positive quantities only - all our ordinates have been

measured up from the base line. In actual work true ac forms appear on both sides

of the zero axis. The same method will work, only the vector additions are more

difficult. For example take a combination of fundamental and second harmonics. To

be sure we get the right wave, we can draw a sine wave (first harmonic) (dashed

lines of Fig. 6) and another of twice the frequency (second harmonic) (dotted

lines). Then we add the two together at a large number of points, and draw the resultant

(solid line).

Now as seen from Table I, a number of our quantities are negative - measured

downward from the axis. Note that when a negative quantity is added, the angle and

distance are the same as for a positive quantity, but the line is drawn backward.

Thus a 210° quantity, instead of being drawn down and to the left at an angle of

30° from the horizontal, is drawn up and to the right.

Drawing the vector polygon for the first and second harmonics of the wave, we

find that the amplitude (peak) of the first harmonic is 10 and the second 5. Had

we started out with a single complex wave like the solid line of Fig. 6, we

would now be able to draw the two waves of which it is composed.

In drawing sine waves like the first and second harmonics in Fig. 6 - or

any combination of harmonics in any wave the reader may analyze - the unit circles

of Fig. 7 are useful. The first circle is drawn with a radius of 10, that of

the first-harmonic peak value. The second has a radius of 5, the second-harmonic

peak. The circles are divided into 30° segments, and the base of the sine wave is

laid out at the same level as the center of the circle. The circle is divided into

12 sections, one for each ordinate, 30° apart. Then a horizontal projection from

the 30° point on the circle to the 30° ordinate will give the correct amplitude

(height) for that point. The other ordinates are similarly handled and the points

connected for a sine wave.

Computing Components Arithmetically

Table I shows how the components of a wave may be determined arithmetically,

without drawing any figures. It is derived from Figs. 3, 4, and 5. First the do

component is found by adding the ordinates and dividing by 12. In the case of our

square wave, it comes to 16.7. This is the value a dc meter would read. To find

the alternating component, each value is multiplied by the sine and cosine of its

angle to find a resultant value and the phase shift. The resultant is divided by

half the number of ordinates used to find the amplitude of the component. This is

actually what we have been doing in the diagrams. For example, a line 10 units long

at an angle of 30° to the horizontal will be found to have risen 5 units.

The end of the line will be 5 units above a point 8.66 units from its origin,

the 8.66 being measured along the abscissa. The sine of the 30° angle is 0.5 and

the cosine 0.866.

It can be seen from Fig. 3 that vector 0 is entirely in the horizontal direction

and does not contribute any vertical component to the resultant vector Z. Vector

1 has a vertical component equal to the ordinate value of the wave (at 30°) times

the sine of 30°. Vector 1 has a horizontal component equal to the ordinate value

of the wave (at 30°) times cosine 30°. We can find the vertical and horizontal components

in the resultant vector by simply adding the vertical and horizontal components

of each of the respective component vectors in turn.

When adding horizontal components a vector moving toward the right on the graph

has a positive value; to the left a negative value. With vertical components a vector

moving up has a positive value; down a negative value. A chart to simplify this

procedure is shown in Table I. The values used are from Figs. 3, 4 and 5.

In our example the vertical component was 74.6 and the horizontal component was

zero. The magnitude

Z = √(x2 + y2) =

74.6. The angle that the resultant makes with the horizontal is

tan Θ = y/x, but the phase shift

is measured from the vertical (OB of Fig. 3) therefore

tan Θ = x/y. We have determined the

phase shift and what remains is to determine the amplitude of the first harmonic.

This is done by taking one-sixth the resultant

Z: 1/6Z = 74.6/6 = 12.4.

With this explanation it should be easy to follow Table I to determine the amplitude

and phase of the various harmonics, without having to draw a figure.

|