|

July 1952 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Many moons ago while in the USAF, I designed

and built a pair of speaker enclosures out of pine wood in the base woodshop. Each

had a separate bass, midrange, and tweeter speaker (and the acoustically

transparent cloth for the front) - all bought at the downtown

Radio Shack. An issue of

Popular Mechanics magazine had guidelines for the cabinet layout and made

passing mention of the need to install an adequate frequency crossover unit in order

to obtain the best performance. That article did not contain any information for

designing your own crossover network, so I went about trying to figure out my own,

based on a fairly limited knowledge of circuit theory and how to match impedances.

There was no Internet back then for conveniently looking up that sort of stuff.

I came up with a circuit that managed to work, but I honestly have no idea whether

the frequency division was anywhere near what I thought it should be. I probably

would have done just as well (or better) to have bought a high quality 3-speaker

unit sold for car hi-fi stereos, and mounted them in the cabinets. See also "Dividing

Networks" in the December 1949 issue of Radio & Television News. Many moons ago while in the USAF, I designed

and built a pair of speaker enclosures out of pine wood in the base woodshop. Each

had a separate bass, midrange, and tweeter speaker (and the acoustically

transparent cloth for the front) - all bought at the downtown

Radio Shack. An issue of

Popular Mechanics magazine had guidelines for the cabinet layout and made

passing mention of the need to install an adequate frequency crossover unit in order

to obtain the best performance. That article did not contain any information for

designing your own crossover network, so I went about trying to figure out my own,

based on a fairly limited knowledge of circuit theory and how to match impedances.

There was no Internet back then for conveniently looking up that sort of stuff.

I came up with a circuit that managed to work, but I honestly have no idea whether

the frequency division was anywhere near what I thought it should be. I probably

would have done just as well (or better) to have bought a high quality 3-speaker

unit sold for car hi-fi stereos, and mounted them in the cabinets. See also "Dividing

Networks" in the December 1949 issue of Radio & Television News.

Loudspeaker Crossover Design

Greater realism through correct dual-speaker phasing - A direct

approach to Loudspeaker Crossover Design

By Norman H. Crowhurst

Some points about the functioning of loudspeaker crossover networks should be

clarified. Most classical treatments derive crossover networks from wave filter

theory, which in turn is derived from the theory of artificial lines. The resulting

designs may not satisfy all the requirements of a crossover network in the best

possible way.

The first and most obvious requirement of a crossover network is to deliver low-frequency

energy to one speaker and high-frequency energy to another. This is usually taken

care of reasonably well, using a roll-off slope to suit the designer's whim.

A second factor (and one that often receives less attention) is the impedance

presented to the amplifier by the combined network. Frequently this varies widely

over the audio range and includes sizeable reactive components in the vicinity of

the crossover frequency. To obtain best performance from the amplifier, a constant,

resistive impedance should be presented to it as a load.

The third requirement often receives even less attention. This is the realism

of the acoustic output from the combination. While this is in some respects a matter

of individual conditioning and preference, it depends fundamentally on certain electro-acoustic

requirements. One of the most important, and frequently the one least considered,

is the phasing, or apparent source of the sound output.

Fig. 1 - The apparent source of sound shifts when speakers are

not in phase.

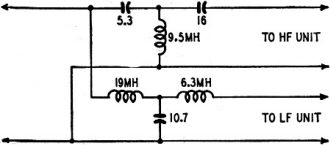

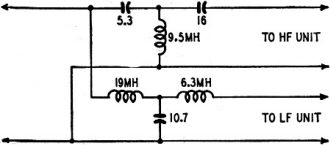

Fig. 2 - Examples of crossover networks for two-way loudspeaker

systems.

Chart for finding exact values of inductance and capacitance

for any of the networks shown in Fig. 2. Use of the chart for a typical solution

(Fig. 2-e) is illustrated in Fig. 3 on the opposite page.

Fig. 3 - How the chart on the opposite page [above] is used to

find inductance and capacitance values for Fig. 2-e. Each speaker has a 40-ohm

voice-coil impedance.

Fig. 4 - Crossover network component values for the circuit of

Fig. 2-e derived by the method shown in Fig. 3.

Tests have shown that phase distortion with single speakers is not normally detectable,

but when two sources are employed, the phase relations between them influence the

character of the radiated sound field. The frequency response as registered by a

good pressure microphone may be flat, but what about the wave-shapes? The pressure

microphone does not answer that, but a pair of human ears can detect such phase

peculiarities, and failure to consider this factor has made many dual-unit combinations

sound noticeably unreal, even though their frequency response may look perfect,

and there may be no measurable distortion.

Source of the Sound

The reader may have checked two speakers for phasing by listening to them while

connections to one of them are reversed. Standing some distance in front of them,

on the center line (as in Fig. 1), when they are correctly phased the sound seems

to come from a point midway between the two units; but when incorrectly phased,

two effects can be noticed: There is a deficiency of low frequencies (due to cancellation

effects) and the source of sound at higher frequencies no longer seems to be associated

with the units actually radiating it. This is because the air-particle movement

caused by the radiated sound is no longer back and forth along a line from the common

source, but approximately at right angles to it. The sound field around the listener's

head is perpendicular to what it should be, causing, through our binaural perception,

the confused impression which may be called "dissociation effect."

A similar dissociation effect will occur with dual units driven by a crossover

system, at any frequency where the two speakers are out of phase. It is best to

keep the two units close together. Some favor putting the smaller unit on the axis

of the larger one and immediately in front of it. But, however the units are arranged,

the dissociation effect can become noticeable if there is an out-of-phase condition

at some frequency near the crossover point. The relative phase at crossover can

be adjusted by positioning the diaphragms on their common axis so the wave from

the low-frequency unit emerges in phase with that from the high-frequency one. When

the units are mounted side by side on the same baffle, the sound should emerge in

phase at the baffle surface.

Constant-Resistance Networks

But how does the crossover network affect the relative phase at frequencies near

crossover? This question often seems to be overlooked, and neglecting it can cause

the trouble just described. Some networks, of the kind employing two or more reactances

for each unit, have values adjusted to give an accentuated frequency rolloff. For

example, the networks shown at Fig. 2, c and d, using values given by the chart

in this article, are of the constant-resistance type, giving a rolloff of 12 db

per octave; the phase difference between the outputs is always 180 degrees; but

using values designed for a sharper rolloff, the phase difference is not the same.

At frequencies near crossover, phase difference changes rapidly. Some out-of-phase

effect in the vicinity of the crossover frequency is unavoidable unless a constant-resistance

type network is used. It is fortunate that this type takes care of both the second

and third requirements mentioned above.

The chart may be used to design any of the six types of crossover network illustrated

in Fig. 2. Those at a and b give a rolloff of 6 db per octave and a constant phase

difference of 90 degrees. For best results the positions of the two diaphragms should

be adjusted so the difference in their distances from the face of the baffle is

about one-quarter wavelength at the crossover frequency. The phase difference will

not be serious within the range where appreciable energy is coming from both units.

The networks at c and d give a rolloff of 12 db per octave, and a constant phase

difference of 180 degrees, which means that reversing connections to one unit will

bring the phase right. The units should be mounted so their diaphragms are in the

same plane.

For cases where the frequency response of the units used requires a roll-off

steeper than 12 db per octave, the networks shown at e or f are recommended. These

give a rolloff of 18 db per octave, and a constant phase difference of 270 degrees.

This means that mounting the diaphragms a quarter-wavelength apart at the crossover

frequency will give in-phase outputs by appropriate connection.

All these networks are designed to present a constant, resistive impedance to

the amplifier over the entire frequency range.

The Impedance Varies

One more point is often overlooked: The networks are designed on the theory that

they are feeding resistance loads of the same value as the nominal voice-coil impedance.

The voice-coil impedance is not pure resistance, so the performance of the networks

is altered. The most serious effect is usually due to the inductance of the low-frequency

unit voice coil. By using networks a, d, or e, each of which feeds the low-frequency

unit through a series inductance, this effect can be overcome by subtracting the

voice-coil inductance value from the network inductance value derived from the chart.

Even if the available data is insufficient to allow this, these networks will minimize

the effect, because the inductance of the voice coil will add very little to the

effective inductance of the network. In the other networks the shunt capacitor combined

with the voice coil inductance will cause a greater variation in input impedance.

Each diagram in Fig. 2 has the inductors and capacitors marked with symbols.

These identify the reference line (in the bottom part of the design chart) to be

used for finding each component's value. Fig. 3 illustrates the use of the chart

to find values for a network of the type of Fig. 2-e, and Fig. 4 shows the actual

circuit calculated in this way for a crossover frequency of 500 cycles, at 40 ohms

impedance.

The input impedance is the same as each speaker voice-coil impedance. Some prefer

to design the crossover network for 500-ohms impedance and use matching transformers

at the outputs to feed the individual voice coils. This method has two advantages:

The two units need not have the same voice-coil impedance; and smaller capacitors

can be used. The range of impedances covered by the chart extends up to 500 ohms

to include such designs.

One modern trend has been to use separate amplifier channels for each unit. In

this case the chart can be used for designing an inter stage filter to separate

the channels, by making the following adjustments: multiply all impedance values

by 1,000 (this means the impedance used to terminate each output as a grid shunt);

change inductance values to henries instead of millihenries; divide capacitor values

by 1,000. Suitable networks for this application are a, c or e, since these allow

the input to each amplifier circuit to be grounded on one side.

The characteristics of the final out-put from any type of network and combination

of speakers can only be predicted accurately if the source (amplifier) impedance

is known. This can be measured with simple equipment by the methods described in

the article "Audio Impedance Measurements," by James A. Mitchell, in the April,

1952, issue of Radio-Electronics.

The amplifier impedance should be as low as possible, and practically constant

over the entire frequency range to be reproduced. With present-day components, this

can be achieved only by using multiple low-impedance output triodes, or by carefully-designed

inverse feedback circuits. The series of articles "Audio Feedback Design," by George

Fletcher Cooper (Radio-Electronics, October, 1950 - November, 1951), covers many

applications of feedback to amplifier circuits.

Posted April 11, 2022

|